Résumés

Abstract

We present a community-driven research project designed to evaluate an innovative land-based healing initiative – a traditional camping weekend – for urban Indigenous families. The initiative was developed and implemented by Under One Sky Friendship Centre in Fredericton, NB, and involved a weekend-long celebration of culture and community. We gathered data from family members, staff, and stakeholders, and completed a thematic analysis and community review before synthesizing results into a narrative summary. Themes included Skitkəmikw (Land), Cəcahkw (Spirit), Skicinowihkw & Nekwtakotəmocik (Community & Family), and Sakələməlsowakən (Wellbeing). These connections are echoed throughout the article by quotes from participants that capture the essence of the experience. Our research helps to fill a knowledge gap in this area and supports the limited body of existing literature in demonstrating that community-led, land-based healing initiatives support Indigenous wellbeing in many ways that mainstream approaches cannot. Future work is needed to scale up land-based healing initiatives that provide community-led approaches to health promotion, and to examine the effects of ongoing participation on long-term health and wellness outcomes.

Keywords:

- land-based healing,

- Indigenous families,

- early childhood education,

- parenting,

- program evaluation,

- Wabanaki,

- Mi’kmaq,

- Wəlastəkwey,

- Maliseet

Corps de l’article

Introduction

I NEVER wanted to be an Indian because when I grew up, there was nothing good about being an Indian. I mean nothing. There were no powwows, there were no cultural events, there was no language revival, there were no traditional things. There was none of that. It was sort of like, “well better for you if nobody knew you were Indian.” That was the message. So, the message needs to be now so that EVERYBODY should want to be an Indian. We should be shooting for that, not just for Indian kids to be proud of who they are, but for other kids to say, “man I wish I was an Indian.” And we could do that. And so, I always say to people they’re not empty vessels; we need to fill those little people up with pride because that doesn’t stay empty, in the absence of pride is shame. You need to fill it up with pride. And the sooner the better because we know a lot of that’s going to spill out, right? There is nothing more beautiful than a two-year-old smudging except a two-year-old teaching another two-year-old how to smudge.

Mi’kmaq Elder, Patsy McKinney

It is well documented that Indigenous (i.e., First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) peoples living on Turtle Island (North America) face poorer health outcomes compared to non-Indigenous Canadians. For example, higher rates of chronic illness (Gionet & Roshanafshar, 2013), substance abuse (Sullivan & National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation, 2012), violence (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls [MMIWG], 2019), and suicide (Kumar & Tjepkema, 2011) have all been widely documented. Colonial methods of cultural erasure and genocide have been ongoing for the last 500 years and have created systematic disadvantages for Indigenous peoples, leading to negative health outcomes and inequities across sectors such as healthcare, education, and child welfare.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015

Despite the colonial history and continuing structural barriers, a grassroots Indigenous community-driven movement for land-based healing is gaining momentum. Such programs address physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental aspects of healing by gathering Elders, youth, and communities together to reconnect to culture, language, wellness, and traditional methods of being, knowing, and doing on land (note: “land” is referred to throughout the article without using “the” in order to avoid objectification). Lamouche (2010, as cited in Robbins & Dewar, 2011, p. 13) states, “In contemporary society, this break with land is the single most important factor in health problems among Aboriginal people.” The importance of place, family, togetherness, culture, and identity are often missing from Western biomedical approaches to healing, yet these are integral to Indigenous health and wellbeing.

Many land-based programs develop around the need to pass on traditional skills, using traditional intergenerational approaches to learning. These cover a broad range of activities, including food preparation, hunting and skinning, smoking meat, fishing, various forms of camping, canoeing, and more (Alfred, 2014; Lessard & Edge, 2018; Moffat, 2017; Noah & Healey, 2010; Office of Environment and Natural Resources NWT, 2005; Pulla, 2013; Radu, 2018; Ritchie et al., 2015; Stevens, 2005; Takano, 2005; Waldram, 2008). Other programs teach traditional crafts and how to participate in the economy by selling them (Pulla, 2013). Some of these include beadwork, quillwork, leatherwork, basket making, drum making, and sewing (Alfred, 2014; National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health [NCCAH], 2011; Noah & Healey, 2010; Radu, 2018; Stevens, 2005; Stuart & Gokiert, 1990; Takano, 2005). These activities have been documented as highly therapeutic and profoundly healing, providing a sense of identity and cohesion in communities.

Spirituality is an integral aspect for the land-based healing programs we reviewed. This spiritual focus can be implemented and enacted in a variety of ways, including storytelling, prayer, visits to historical sites, learning traditional songs and teachings from Elders and knowledge holders, ceremony, and the use of language (Alfred, 2014; Hare, 2012; Irlbacher-Fox, 2014; Lessard & Edge, 2018; Miyupimaatisiun Chisasibi Wellness, 2014; Moffat, 2017; NCCAH, 2011; Pazderka et al., 2014; Pulla, 2013; Radu, 2018; Radu et al., 2014; Ritchie et al., 2015; Roué, 2006; Stevens, 2005; Takano, 2005). The consistent focus on spirituality is part of reclaiming this aspect of life as an integral part of wellbeing, a focus that is frequently absent in colonial health care.

Evaluations of land-based healing initiatives have reported a range of positive outcomes such as simply having fun, developing an interest in participating in community and land-based activities, renewing the sense of value of land and the role of land and water in culture, feeling happier and less depressed after camps or other programs, and finding a strong sense of self and place in community (Healey et al., 2016; Lessard & Edge, 2018; Moffat, 2017; Noah & Healey, 2010; Pulla, 2013; Radu, 2018; Ritchie et al., 2015; Waldram, 2008). Participants also report experiencing spiritual realization and an “awakening” to the “good life” (Ritchie et al., 2015). Taken together, these initiatives highlight a broad range of potential positive outcomes for participants. However, ongoing evaluation of individual programs is important given the diversity of initiatives reported in the literature, as well as sociocultural differences among Indigenous groups.

In this article we describe an Indigenous community-driven program evaluation research project conducted in partnership between Under One Sky (UOS) Friendship Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick (NB) and the University of New Brunswick (UNB) Faculty of Nursing. The evaluation focuses on a grassroots land-based healing initiative that was designed and implemented by UOS. Essentially, the initiative is a family camping weekend developed on a foundation of Indigenous worldviews and family-centredness. Our primary research objectives were to explore the perceived benefits of the program, identify potential areas for improvement, and provide data that UOS might leverage to secure sustainable funding.

Under One Sky’s Family Camping Weekend

Under One Sky is a non-profit organization that offers programs and services primarily to urban (i.e., off-reserve) Indigenous people living in and around Fredericton, NB. One of UOS’ core programs is the Aboriginal Head Start for Urban and Northern Communities (AHS) and early childhood education (ECE) program for Indigenous children funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Within this program, UOS developed the Take it Outside (TIO) initiative, which is a modified ECE program where children learn outdoors – from land, creatures, each other, and the educators – at least twice per week. Based on input from community members this initiative grew into a culture and land-based healing initiative – the Family Camping Weekend – that aims to foster physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental wellbeing in an outdoor environment. The Family Camping Weekend is delivered about an hour outside of Fredericton, NB over the course of three days and two nights. Families sleep in cabins, a communal bunkhouse, or a prospectors’ tent, and participate in cultural activities such as drumming and singing, canoeing, community feasts, medicine walks, storytelling, and ceremony. Elders attend and provide teachings throughout the weekend. All these activities were included in the family camping weekend we evaluated during this project.

Methodology

We adopted Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall’s concept of Etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing) in this research (Bartlett et al., 2012) and applied it alongside a community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology (Baydala et al., 2015; Viswanathan et al., 2004). Applying Western approaches to Indigenous research has the potential to impose inappropriate values on the research and has a legacy of removing ownership and control from the organizations and communities in which the research took place (First Nations Information Governance Centre [FNIGC], 2020). Additionally, research has historically been done on Indigenous communities, rather than with them, and prioritized Western knowledge and values above all else. Etuaptmumk acknowledges the benefits that can be gained from combining multiple perspectives and recognizes the value in different ontologies and epistemologies (Martin, 2012). We enacted this approach from the outset of the project by forming a diverse team and regularly questioning decisions, interpretations, etc., from our multiple perspectives. CBPR is a “Western” methodology that aligns with principles of OCAP®, Etuaptmumk, and Indigenous research because of its focus on creating positive social change in partnership with organizations and communities (Wallerstein et al., 2018; Viswanathan et al., 2004). In this project, CPBR enabled us to undertake a rigorous program evaluation that was responsive to the needs of the community, open to our multiple ways of thinking about, and doing, research, and where the primary focus was community benefit.

Planning

We formed a project advisory group (PAG) of stakeholders, which included the Executive Director of UOS (a Mi’kmaq Elder), a non-Indigenous researcher of European ancestry from the UNB Faculty of Nursing, an Indigenous family member of Wəlastəkwey ancestry, representatives from PHAC of Inuit and European ancestry, and the Director of a second Atlantic region AHS Program of Inuit ancestry. Four bi-weekly meetings were held during the planning phase of the project to inform the research process. This process included drafting a logic model (Public Health Ontario, 2016) in order to identify inputs, activity outputs, and desired outcomes, and to provide a framework for evaluation. We organized outcomes in the logic model according to the six pillars common to the 134 AHS Programs across the country: Culture & Language; Health Promotion; Nutrition; Education and School Readiness; Parental & Family Involvement & Community; and Social Support.

Concurrently, we formed a research support team consisting of four undergraduate nursing students. Three of the students were Indigenous, identifying as Wəlastəkwey, Cree, and Métis and a fourth chose to identify as a settler. The research support team was mentored by the UNB researcher and Executive Director at UOS. To facilitate relationship building, the students volunteered at the AHS program during the project development to learn about the program, get to know family members, and assist with educational activities.

We obtained ethics approval from the Faculty of Nursing’s Research Ethics Committee and the University Research Ethics Board (#2018-101). The study also underwent community review by the PAG in keeping with the Urban Aboriginal Knowledge Network’s (UAKN) Guiding Ethical Principles (UAKN, 2016). OCAP® principles were maintained throughout the project (FNIGC, 2020). We honoured family members’ contributions throughout the project, and to facilitate their participation, by providing grocery cards valued at $25, and by paying for childcare and transportation expenses when necessary. We provided a gift of tobacco, considered a sacred medicine in Wabanaki territory, to the Elders who participated to honour their wisdom. The gifting of tobacco “is done to ensure things are done in a respectful or good way” (Lavalleé, 2009, p. 21). These honoraria and expense reimbursements are consistent with UOS’ guidelines.

Recruitment and Participation

The Executive Director at UOS identified potential participants. The primary participant pool included families with children in the AHS program. We also recruited stakeholders who were involved in the AHS program and familiar with the family camping initiative. In total, five family members and 14 stakeholders participated in the research.

We recruited family members by sending a letter home with children to share with their caregivers explaining the research project and inviting them to participate in the Family Camping Weekend and the associated research project. Letters were sent home with 11 children and five families indicated their interest in attending the camping weekend. All five families who responded to the invitation also indicated their interest in participating in the research, although participation was not a requirement to partake in the initiative. A member of the research team contacted these families prior to the event, explained the project in detail, and obtained verbal consent. We reviewed consent forms at the event with each participant and obtained written consent. Student researchers also contacted 14 stakeholders, including UOS staff, Elders, members of the PAG, and others with knowledge of the initiative, by phone or email, to invite them to participate in the study. Those who agreed provided verbal or written consent during a follow up interview.

Four families (five parents and nine children) attended the event, along with an Elder, five staff members, four student researchers, and the nurse researcher. The families identified as either Wəlastəkwey or Mi’kmaq and so for the remainder of this article, where applicable, we will refer to the group as Wabanaki, under which Wəlastəkwey and Mi’kmaq commonly identify (Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre, 2020). Table 1 outlines the contributions of the people involved in this project. Ongoing involvement of such a diverse group throughout all stages helped us to maintain Etuaptmumk and ensure our decisions were based on community priorities.

Table 1

Contributions of Those Involved in the Project

Data Collection

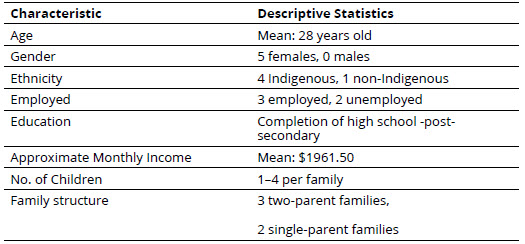

We interviewed each family member over the phone prior to the excursion to complete a participant information form. Questions consisted of demographic data and a short questionnaire asking: why they chose to attend the Family Camping Weekend; what their definition of family is; how the initiative benefits their family; and what needs they feel the initiative addresses. Demographic information for the family member participants is presented in Table 2.

At the Family Camping Weekend, we provided participants with journals to record their thoughts over the weekend. The four undergraduate research assistants and the researcher who attended the Family Camping Weekend compiled their own feedback and observations at the end of the event. We chose not to directly collect data from participants during the initiative because the PAG felt it would take away from the families’ experiences.

One week after the Family Camping Weekend, we held a research circle with family members at UOS. The research circle began with a smudge, and a traditional object (hand-carved turtle) was used as a talking stick. The research circle was audio-recorded and later transcribed for analysis.

Table 2

Demographic Data for Family Members

After the Family Camping Weekend, we arranged conversations with stakeholders to discuss their perspectives on the initiative. Conversations occurred either at their homes, place of work, or over the phone, depending on their preference, and were audio recorded. We asked stakeholders about their relationship and involvement with the AHS program, how they see the program and land-based healing initiative benefiting families, what needs the initiative addresses, the challenges it faces, and areas for improvement.

Data Analysis

We began by uploading data from the journals (n = 4 family members), research circle (n = 5 family members, 4 student co-researchers, 26 pages), and interviews (n = 17,108 pages) to nVivo12 (qualitative data analysis software) for analysis. We then used framework analysis to identify themes. Framework analysis is a structured approach to qualitative analysis where a team-based approach can be used (Furber, 2010). Each member of the team began by coding a common transcript using the following two questions to guide their analysis: What are the benefits of this initiative for families? How could the initiative be improved? We purposefully took an inductive approach to analysis at this stage because the PAG indicated an interest in identifying unintended outcomes (i.e., those not necessarily contained in the logic model). After coding the initial transcript, we met and collaboratively identified initial themes and organized these into a coding framework. We then divided the remaining data amongst the student co-researchers who applied the framework to the remaining transcripts. About halfway through this process, we met again to review coding and make any necessary adjustments to the framework. We then completed coding and drafted a summary of the results. We also conducted a second round of deductive coding to label all instances where participants referenced specific outcomes from the logic model.

Etuaptmumk was an important part of this process; as we compared our initial codes, we had long discussions about the meaning behind the labels we applied and shared our perspectives on how we felt these connected (or did not connect) with participants’ experiences. For example, one of the student co-researchers is familiar with local culture through lived experience. She was able to give background and context to expand the team’s understanding of the data. The other students were able to broaden that perspective by sharing knowledge rooted in their own unique backgrounds. We consistently raised questions about each other’s analytical choices in a spirit of inquiry, rather than criticism. This approach, in addition to follow-up engagement with participants, enabled us to honour their knowledge while applying a typically Western approach to data analysis.

After preliminary analysis was complete, we organized a community meal with staff and participants to present the results, seek feedback, and discuss next steps. This was an important part of our CBPR approach because it brought the community back into the research process. The Executive Director of UOS gave feedback throughout the analysis. However, this aspect of the research was the most removed from the community. Feedback from the engagement event helped us to better understand the results and particularly what aspects were most meaningful for the community. Thus, we were able to maintain our focus on benefit to the community and re-establish the community’s role as driving the project. We incorporated feedback from the engagement session into our analysis, which we present here as a narrative synthesis. Family members and UOS staff reviewed this article, gave a final round of feedback, and approved our request to publish prior to submission.

Psiw-əte ntələnapemək (All My Relations): Results

The overarching message from participants was exceedingly positive. Although we will not present the logic model outcomes in detail here, the most commonly referenced outcomes were: rediscovering a connection to land; opportunities for parents to engage in traditional activities with their children; coming to see being outdoors as a positive experience; opportunities to participate in traditional activities; and improvement and regaining of cultural knowledge. The success of the Family Camping Weekend can be seen in that all outcomes from the logic model were organically referenced in the data (i.e., we did not purposefully ask about any specific outcome). Detailed results from the model were provided to UOS and may be made available upon request to the author.

In presenting this thematic analysis, we have relied heavily on participants’ own words with minimal rephrasing or interpretations. Rowett (2019) writes that using direct quotes from participants and interviewees honours Indigenous voices when researching alongside communities. Even with the use of extensive quotes it is difficult to replicate participants’ emotional responses when reflecting on this activity and the AHS program in general. There were moments of overwhelming gratefulness, tears, laughter, and a sense of relationship and togetherness in the research circle. The primary themes identified during analysis are described in detail below and include Skitkəmikw (land), Cəcahkw (spirit), Skicinowihkw and Nekwtakotəmocik (community and family), and Sakələməlsowakən (wellbeing; feeling strong in myself).

Skitkəmikw (Land)

Being in nature facilitates children’s and families’ understanding of the relationships between all things. For example, one Elder participant says,

It’s nice for the kids to understand that they’re related to the standing people: the trees. They’re related to the insects that are on the ground. They’re a part of everything that is there, and everything that’s out there is a part of them.

Through the Family Camping Weekend, children and family members built on their relationship with nature. The way nature is referred to by participants implies nature is an active, living entity, the first teacher, a companion, and one who shares wisdom and provides support. By interacting with land, children and parents learn valuable skills and lessons. Many of these cannot be experienced in the classroom because of the disconnection with the natural world and limited opportunities to engage with Mother Earth. As an Elder explains,

… these certain ones, are going to help us save the planet. I mean, we’re destroying this planet as adults, and these guys aren’t like that. They want protection, they want to see the plants, they want to see the animals, they want to know that a rabbit has a house, just as a deer, or a moose, or a bear. They’re non-judgmental, and to me, that’s the most amazing part. We haven’t restricted their learning outside, we haven’t. Inside, we have, it’s controlled. Outside is not as controlled.

Families and staff reported positive changes in their children when out on land, such as increased focus and attention, physical benefits and fitness, and improved behaviour. Two families had children living with autism and noted improvements in their social involvement and that the Family Camping Weekend helped to decrease their “flight risk.” Families also discussed the way their parenting changed from “micromanagement” to “freedom” for their children. They felt confident and comfortable allowing their children to experience their environment when on land compared to urban settings. One participant makes a point that being outdoors, where children and parents become comfortable and feel safe, parents are less protective and more relaxed about their parenting. This in turn allows children to be more creative and imaginative. A family member highlights this comfort:

Just being outside back in the woods, like they were happy as can be running around playing … Usually we are hesitant to bring [our son] anywhere because he’s autistic and he’s a flight risk. But out there he stays within the boundaries and we let him explore … and he just loves it, it’s just the freedom out there … Cause when we’re here within the city … it’s like micromanaging their movements and they have to be constantly monitored and you can tell it takes a toll on them too … when we’re out there at the campground … we could cut those ropes loose a little bit and just let them go and they love that freedom.

The support UOS provides allows parents to focus on their families’ experience, which in turn fosters their connection to land – Skitkəmikw. As one government stakeholder highlighted, this activity gives participants an opportunity to experience “their traditional unceded territory.” Land, in a traditional sense, is far more recognizable outside of the concrete and harsh angles of the city.

Cəcahkw (Spirit)

Families discussed their spiritual connection to land deepening through their participation in the TIO program and Family Camping Weekend. They came to see the outdoors as a positive experience and began to align themselves with the cycles of earth. One staff member talks about connecting with “the flow of things” and natural processes in life and how this connection can help ground and center one’s self:

Somebody came up with a quote last summer, “it’s not dirt, it’s Mother Earth,” and it’s all fertile and they get to see the whole cycles of rebirth and decay and the quietness of winter and everything sleeping and then everything coming alive again. From an Indigenous worldview, that’s spiritual. You see yourself as a part of the circle, you are integral to it, and that’s the best place to get to that, I think.

It was clear that this type of connection to one’s spirituality is more easily fostered on land. Another staff member explained:

That’s who we are, so we are connected to the land, we have always had a strong connection to the land and that is the spiritual, that’s what the spirit is. I think it’s how we present ourselves … how we stand in who we are … You can’t get any more spiritual than that because we understood our place and … you can’t do that in these institutions inside.

Staff member

One morning, the adults had a chance to participate in a pipe ceremony while their children ate breakfast at the lodge. During the ceremony we had some animals pay us a visit. After receiving teachings about the pipe, and doing the ceremony, we all stood at the edge of the lake and a participant sang the Wəlastəkw song to our backs as we offered tobacco to the water. While doing this, an eagle flew overhead, and a moose stepped out of the forest to witness the end of the ceremony and carry our prayers as one participating family member describes:

Connecting back with mother nature, that was amazing; being able to be out there and reconnect with Her and you know, the spirit animals that came to visit us when we were having the pipe ceremony, that was powerful. It shows that they’re listening. And seeing the eagle; they say he flies closest to the sky, closest to the Creator, so all those prayers that you guys had or that we said there, he came and brought them up to the Creator …

Other participants discuss the ways in which family members connect with traditional ways of being and highlight the important connection between language, spirituality, and wellbeing that is promoted by this initiative. One staff member explained:

It’s hard that the families we are serving are urban Aboriginal and they may not have access to the language or the culture anywhere else but Under One Sky. So, when you take it outside it allows you to apply some of that culture in a way that you can’t inside of a classroom. I think it is an amazing opportunity to learn more about their language and ceremonies, they have done medicine walks, hikes, smudging, just learning the Indigenous Maliseet [exonym of Wəlastəkwey] names of animals and plants and even the history behind it.

Staff and family members told us that the children often pick up the language faster than their parents. Then they become the language teachers. Learning new words from their children brings a sense of pride and connection back to the entire community’s identity, Indigeneity, and spirit. An Elder who participated in the weekend highlights the importance of giving our children the opportunity to teach us:

The two closest groups to the creator are the ones that just came into the world and the ones getting ready to leave. And if that child is coming from [the] spirit world into this creation, then how come we’re not asking them for some advice, especially when they have developed the language? They’ll tell us. They’re not shy at telling us.

We separated Cəcahkw (Spirit) from the other themes when we organized this narrative, but one Government stakeholder highlights the interconnectedness of people’s experiences and outcomes:

The spiritual piece just gets back to that connection to Indigenous culture, the pride in the culture, the pride in the language, whether it’s strengthening or revitalizing, whether it’s reconnecting or if it’s learning new for some families that may have been away from their culture for quite a long time.

Skicinowihkw and Nekwtakotəmocik (Community and Family)

Coming together, all of us together doing the family camp. They’re building relationships with each other and then they end up supporting each other later in other areas.

Participants discussed how the activity allowed them to reconnect with land, culture, and spirituality as a family, not just as individuals. The families and parents that organizations like UOS serve often have inadequate personal and financial resources to access activities that might be considered unessential, despite their potential benefits. Under One Sky provides gear, transportation, childcare support, activities, meals, and so much more to facilitate the Family Camping Weekend. Therefore, families participate in this and similar initiatives run by the centre with little to no cost involved. The Family Camping Weekend may seem like a brief intervention but for many participants, it provides a rare opportunity to leave the hustle and bustle of life behind, reconnect to Mother Earth, and have time to enjoy one another. An Elder explained how the experience is a rare treat for families:

It [brings the family] closer together because of this one-on-one time and you know what’s too bad about the kids nowadays, like back home it’s such a hurry-up life. It’s so expensive to live out there in the modern world how everything you [have to] pay for in order for families to survive financially, to pay the rent and their car bills, or phone bills, groceries, and clothing. They both have to work, so they’re juggling time and not spending as much time with their children. So just this one weekend being out here, it’s like a treat for both of them.

Parents also discussed having time to reflect on their parenting and get to know their children in a deeper way. Many discussed the benefits of “unplugging” when at the Family Camping Weekend. They reported that their children were more engaged with their surroundings, and they were able to leave their electronics at home. As one parent explained,

It just made me realize how grateful I am for the children I have … and just made me realize how sometimes I can be so hard on them when I don’t need to because they’re really good kids … I just need to step back and let him be a child … Seeing my kids so happy and being themselves, it just made me realize that I can do a lot better. I can take my kids out a lot more.

Not only did individual families come together and strengthen their interpersonal bonds, families developed and strengthened relationships between other families and staff. The four families built memories together and bonded over a shared cultural, outdoor experience (See Figure 1). They all supported one another over the weekend in many ways.

… out there at the camp it truly was community. All of us together; we were all like one. We were all willing to help each other any way we can. Whether it be something with the fire, or with the food, or with our kids or something like that. Everybody was pitching in, and that was the most amazing feeling. To be able to have that moment to just exhale and know that you had all that support around you was really nice.

Figure 1

Bonding Around the Campfire

In particular, family members felt that being around others who shared a common social and cultural background, and understood each other’s daily struggles, was profound:

… having a friend there who was … knowing how I felt and knew that I’m the only parent with my kids, and just giving me the opportunity to actually experience that with my son. And I’m so grateful because I got to see him grow and expand in great ways. And I wouldn’t have been able to do that if I wasn’t able to go on the canoe, so that was a big, huge highlight for me was just having someone there and just really supporting me to do those things and knowing that it’s not easy for … it’s not easy for … singles … its’ just [having] that support system. And so, even though I don’t have a partner with me and my children, having my really good friends here and supporting me and being that partner for me, is just very nice and I’m grateful for that. So, thank you [other parent].

One Elder commented on how the Family Camping Weekend and the TIO program in general promotes community in a way that mainstream educational systems cannot:

I think that over the years [dominant society] has taught our residents to be more individual as compared to more community, because in the earlier times it was all community. It was all community-driven, community-purposed, and what I’ve seen over the passage of time is as our residents leave, they go on to university. It’s almost like it’s taken the Indian out of them and put individual needs, where cars, houses, and ego-gifts gets its way rather than the individual saying “okay what can I do for my community? It doesn’t matter to me what education skills I have, unless I share them in the community and say yeah, I want an opportunity to brainstorm.” And I find that’s the difference with these kids as compared to a child that’s going out in dominant society and all he or she has got to do is fend for themselves in that environment. Where these guys it’s group; when they see each other and when you see the smiles and they’re looking for each other, it’s a group! Their ego is gone, they’ve [forgotten] all about that. It isn’t about their needs anymore.

Sakələməlsowakən (Wellbeing; Feeling Strong in Myself)

The following quote from a staff member illustrates the foundation from which this land-based healing initiative was developed, and encapsulates the benefits that families experienced.

… the whole wellness piece about it being non-Euro-Western is that wellness is not just about your blood pressure and your weight and all of that, it’s about how you’re feeling and that word I used, Sakələməlsowakən, that gave me goosebumps when, and I don’t know if we ever told you that story. Well, when we were developing a wellness program and I said to [our language instructor] “I would like to use a Maliseet term for that,” so she went to her Elder and the Elder was like, “what is it you’re trying to do?” Because the language doesn’t translate word for word, so he had to have a sense, the essence of what we were trying to do so I told [our language instructor] and she went back and she told him and he said “Sakələməlsowakən” and so it gave me goosebumps because it means “feeling strong in myself.” And I’m thinking, “isn’t that what wellness is?” So, it’s not just feeling muscle strong, it’s feeling confident, feeling good about your wellness, your family wellness, your community wellness, your cultural wellness …

Figure 2

Canoe on the Edge of Lake Waiting for Parents and Children

This type of initiative is critical for the early developmental years of Wabanaki children and their families because of the pride and empowerment it instills. Gaining knowledge about how to be outdoors provides a sense of confidence and empowerment to participants. One mother proudly says, “I know how to make fires and I know how to chop wood,” because of her experience during the camping weekend. Another participant recalls that during a previous experience learning how to light a fire with flint, “there was one girl – she was not giving up … [when she got it] she screamed she was so excited she made me jump.” According to UOS’ Executive Director, this sense of accomplishment is important because Wabanaki children need to see their parents feeling good about themselves and family and culture more often. One staff member emphasizes this using the traditional canoe (see Figure 2), whose design hasn’t changed significantly in thousands of years, as an example:

And to understand that what happens [too often] is much of who we are [as Wabanaki] gets minimized and I get so irritated and so pissed off cause you’d say be talking about [something traditional – the canoes for example] and people would go wasn’t that clever? It wasn’t clever, it was brilliant – we were brilliant, but we never ever get a chance to get portrayed that way and we need to do that with our kids. So, we need to say, “look how brilliant we were in that!” We did that. We learned to do that from observing the environment. We were so connected to the land, to the environment and what it offered, and so that’s what we need to [do], get our kids to the place where they’re excited about who they are.

Aside from feeling a sense of empowerment from learning new skills and connecting with others, participants also felt a stronger sense of Sakələməlsowakən through immersion in nature and increased physical activity. One staff member discusses the positive, strengths-based approach to physical fitness that emerged on the Family Camping Weekend. She mentions that going to the gym can be challenging and intimidating, but being outdoors enables you to participate in “functional fitness;” because it is unintentional and there is less pressure and fewer expectations around success. This form of fitness allows you to feel well without trying to feel well.

I think it benefits families – I think as human beings we all have, innately have, this strong connection with nature. And when you are able to experience nature on a regular basis I think it’s, you can see a gradual change in a personality and a change in the way that people respond to situations – of a stressful situation, or I just see people able to regulate themselves a little bit better when they foster that connection. And even if, for example the weekend that we did with the whole families, having that space away from the hectic world and the hectic life that we seem to always be living, is really, really helpful with just finding your inner self again and just centring yourself and being able to remind you where you came from and that we are a big ecosystem.

One participating staff member summarizes why initiatives such as the Family Camping Weekend are so important for promoting community wellbeing and recovering from colonization:

And the general belief is that Indigenous people are in the situation they’re in by their own demise [and] if they just got off their lazy asses and go got a job … But what people don’t understand is that whole historical trauma piece that [has impacted] multiple generations. But what incredibly resilient people to have survived some of what they’ve survived and they’re still putting one foot in front of the other. And they want the same thing everybody else wants, they want a good life. They want a comfortable life, they want the very best for their children, they sometimes just don’t have the bits and pieces. And so that’s what I wish I could change. We’re working really hard around that and I think we have some people that are listening now. I hope. So [taking kids outside], doing the family camp, they’re just small things. But it’s a start so we build the relationship with them. We take the time to build the relationship and we don’t do the, “well you shouldn’t be doing this, and you shouldn’t be doing that,” thing. We just simply build the relationship.

Discussion

This article describes a community-driven evaluation of a land-based healing initiative for urban Indigenous families in the Fredericton area. The research team worked closely with a PAG to design a project that would evaluate the degree to which the Family Camping Weekend meets intended outcomes and whether there are unintended positive outcomes from the initiative. The evaluation was undertaken to meet the community-identified need for systematically collected data that could be used to improve future offerings of the Family Camping Weekend and provide evidence to support proposals to fund the initiative on a long-term basis.

Published evaluations of land-based healing initiatives in the academic literature have reported a range of positive outcomes, from simply having fun (Moffat, 2017) to increased resilience (Healey et al., 2016) to spiritual and cultural (re)awakenings (Ritchie et al., 2015). Under One Sky’s Family Camping Weekend similarly produced a broad range of outcomes. Participants reported positive benefits in the AHS program’s core areas: culture & language; health promotion; nutrition; education and school readiness; parental & family involvement & community; and social support. Beyond these program pillars, participants spoke of positive experiences related to land, spirit, community and family, and wellbeing. The breadth of positive outcomes encountered by participants of land-based healing programs is due at least in part to the alignment of these activities with traditional values and worldviews (Wildcat et al., 2014).

One of the principles underlying the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Calls to Action is that Indigenous peoples have a right “to live with dignity as self-determining peoples with their own cultures, laws, and connections to land” (TRC, 2015, p. 184). The Family Camping Weekend, and many other land-based healing initiatives, are grassroots programs run by the community for the community. However, the organizations who take the lead on these initiatives often have to walk in two worlds: participating in a colonial capitalist paradigm in order to secure and maintain funding, while promoting and implementing the Indigenous paradigms that they know to be most beneficial to the community (Freeland Ballantyne, 2014). Despite this tension, land-based initiatives can still be delivered in a safe and meaningful way and achieve broad outcomes.

Our results highlight the holistic nature of this land-based healing initiative. Participants connected deeply with all their relations in a way that is often not possible in an urban setting. The camping weekend became a celebration of the relationship between all things that provided an opportunity to restore participants’ sense of wellbeing. Indigenous frameworks and concepts for wellbeing are diverse but have a common focus on balance between multiple aspects of health (Moffat, 2017; Pazderka et al., 2014; Radu, 2018; Ritchie et al., 2015). Land-based healing initiatives simultaneously address many of these different aspects, and because of the range of opportunities to engage (e.g., spiritually, socially, physically, etc.), the same activity can meet different needs for different individuals (Radu, 2018), thus acting to restore balance. Because of this, we feel the healing potential for this deinstitutionalized, land-based approach, and other similar initiatives, must not be overlooked.

Importantly, Indigenous community organizations, such as UOS, are better positioned in many ways to provide health promotion services for the Indigenous population. They have a deeper understanding of what their community needs, an understanding of the cultural nuances required to meet those needs, and the necessary relationships and trust to work with those receiving services. There is substantial evidence for positive health outcomes when communities are empowered to deliver culturally relevant care for individuals and families (Chandler and Lalonde, 1998). However, organizations such as UOS often lack the capacity to deliver these services at scale. This can be due to discriminatory legislation, lack of sustainable funding, and “marginalization of indigenous knowledge” (Blackstock and Trocmé, 2005, p.12). Mainstream support of, and involvement in (rather than leadership of), initiatives like the Family Camping Weekend, is likely to reduce health inequities and provide meaningful and productive opportunities for cross-cultural learning, collaboration, and capacity-building.

Limitations

This study has provided valuable data about UOS’ Family Camping Weekend and provided some insight into land-based healing initiatives in general. However, it has several inherent limitations. First, results are based on a single event. This provides a somewhat narrow view of the experience and may limit our understanding of repeated involvement in a sustained program. Also, the sample was small, and participants were likely to be positively biased towards the initiative because they were the people who called for it to be developed. That said, our (i.e., the research team’s) experiences in the activity alongside family members, as well as input from stakeholders, corroborates the overwhelmingly positive results. Finally, Indigenous cultures vary greatly across Turtle Island and so what works for us in Wəlastəkewikok may not work elsewhere. That is why land-based programming must be grounded in place, history, and the local way of being, learning, knowing, and doing, and must represent the needs of the local community (Moffat, 2017; Radu et al., 2014). The consistency of positive outcomes across the land-based programming reported in the literature suggests that this approach to promoting wellbeing is broadly applicable.

Recommendations

Based on the consistent positive results from those involved, we recommend that this initiative be offered more regularly throughout the year. We held a knowledge translation event to share preliminary results with the community and attendees were excited to repeat the initiative and suggested doing so once per season. If this is possible, outcome evaluation and monitoring should continue in order to maintain a focus on continuous improvement and obtaining sustainable funding.

More broadly, we recommend scaling up this and similar land-based healing initiatives because of the wide range of potential benefits to individuals, families, and communities. This scaling up could involve both increasing the number of participants per activity, while taking care to maintain its quality, and increasing frequency. The urban Indigenous population across Canada is one of the fastest growing population segments in the country (Harrop, 2018); the scaling up of initiatives such as the Family Camping Weekend is needed. In order to meet growing demand, UOS has begun to offer training for other similar organizations to take their children and families outside.

Finally, federal and provincial governments and associated institutions should endeavour to increase support for community-led wellbeing interventions such as the Family Camping Weekend. Such partnerships have the potential for improving health outcomes for Indigenous people, thus addressing the disproportionate health burdens they experience. We acknowledge that many of these institutions are working towards improved understanding of, and relationships with, Indigenous communities. We also suggest that a priority for this work should involve transferring power and control to Indigenous organizations, and enabling them to take the lead on development, implementation, and scaling up of health promoting initiatives, while providing support and expertise as directed by those organizations.

Conclusion

The following excerpt from a participating family member embodies the essence of why and how the Family Camping Weekend was a success:

I could just hear my son and his friend out there, and then when he comes in the cabin, he was so proud – “me and my friend were singing mom, and I was dancing!” He said, “hold this drum so I can go out there and dance” and it’s dark and he’s out there powwow dancing.

Land-based healing initiatives are emerging in response to ongoing trauma caused by colonialism throughout Turtle Island (Radu, 2018). Each program evidenced in the literature demonstrates profound healing, improved community connection, and resilience. Similarly, the Family Camping Weekend benefited families by fostering Sakələməlsowakən (wellbeing; feeling strong in myself) through connecting participants to land, culture, and spirituality. Our data supports the existing literature regarding land-based healing initiatives: being on land fosters wellbeing, spirituality, and a sense of coherence in community. Under One Sky provides integral support to the families involved and creates a supportive environment for families to come together. As Elder Patsy McKinney says, “It’s a change your life program.”

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

We would like to dedicate this research to the beautiful and amazing parents involved. You consistently put your children’s needs before your own, make sacrifices so that your children can attend school, have food to eat, stay connected with their culture, and have a chance at a successful life. You consistently show strength, determination, persistence, and perseverance. There are many barriers making it more difficult for you to support and nurture your family, but you stand up to them over and over again. Your stories are inspiring. Thank you sincerely for sharing your lives with us. I hope that we, and everyone who reads about your experiences, will be better off because of your gift to us.

Wəliwən to the following family member-participants (each of whom consented to having us name them in this paper as a form of respect): Jenny Perley, Kelsey Mehkweyit-Wiphon (Red Feather) Nash-Solomon, Sasha Augustine, Laura Megwe’g Pipugwes Martin & Shawna Cyr-Calder

Bibliography

- Alfred, T. (2014). The Akwesasne cultural restoration program: A Mohawk approach to land-based education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 134–144.

- Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

- Baydala, L., Ruttan, L., & Starkes, J. (2015). Community-based participatory research with Aboriginal children and their communities: Research principles, practice and the social determinants of health. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 10(2), 82–94.

- Blackstock, C., & Trocmé, N. (2005). Community-based child welfare for aboriginal children: Supporting resilience through structural change. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, March 2005(24), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976312.n7

- Chandler, M., & Lalonde, C. (1998). Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346159803500202

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2020). The First Nations principles of OCAP®. https://fnigc.ca/ocap

- Freeland Ballantyne, E. (2014). Dechinta Bush University: Mobilizing a knowledge economy of reciprocity, resurgence and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 67–85.

- Furber, C. (2010). Framework analysis: A method for analysing qualitative data. African Journal of Midwifery, 4(2), 97–100.

- Gionet, L., & Roshanafshar, S. (2013). Select health indicators of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit. Statistics Canada.

- Hare, J. (2012). “They tell a story and there’s meaning behind that story”: Indigenous knowledge and young Indigenous children’s literacy learning. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 12(4), 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798411417378

- Harrop, V. (2018). Making the invisible visible: Urban Indigenous families, systemic poverty and homelessness in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Under One Sky Friendship Centre. https://www.uosfc.ca/resources/

- Healey, G., Noah, J., & Mearns, C. (2016). The Eight Ujarait (Rocks) Model: Supporting Inuit adolescent mental health with an intervention model based on Inuit ways of knowing. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 11(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijih111201614394

- Irlbacher-Fox, S. (2014). Traditional knowledge, co-existence and co-resistance. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 145–158.

- Kumar, M., & Tjepkema, M. (2011). Suicide among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit (2011–2016): Findings from the Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC). Statistics Canada.

- Lavallée, L. (2009). Practical application of an Indigenous research framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800103

- Lessard, S., & Edge, L. (2018). On the land education: Deh Gáh Elementary and Secondary School. Indspire. https://indspire.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/DehGah-Final-4.pdf

- Martin, D. (2012). Two-eyed seeing: A framework for understanding Indigenous and non-Indigenous approaches to Indigenous health research. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(2), 20–42.

- Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre. (2020). What is the Wabanaki Collection?https://www.wabanakicollection.com/about/

- Miyupimaatisiun Chisasibi Wellness. (2014). The Chisasibi land based healing program. Chisasibi Wellness. https://www.chisasibiwellness.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Chisasibi_NNAPFtoolkit_finaldarft1.pdf

- Moffat, A. (2017). Land, language, and learning: Inuit share experiences and expectations of schooling. [Doctoral dissertation, York University]. YorkU Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. (2011). With Dad: Strengthening the circle of care. https://www.nccih.ca/docs/health/RPT-WithDad-EN.pdf

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: Executive summary of the final report. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/

- Noah, J., & Healey, G. (2010). Land-based youth wellness camps in the north: Literature review and community consultations. Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre. https://web.archive.org/web/20170825210823/http://www.qhrc.ca/sites/default/files/component_1_-_lit_review_-_jun_2010.pdf

- Office of Environment and Natural Resources. (2005). Take a kid trapping report. Government of Northwest Territories. https://www.enr.gov.nt.ca/sites/enr/files/reports/take_a_kid_trapping_program_report_2005-07.pdf

- Pazderka, H., Desjarlais, B., Makokis, L., MacArthur, C., Hapchyn, C. A., Hanson, T., Van Kuppeveld, N., & Bodor, R. (2014). Nitsiyihkâson: The brain science behind Cree teachings of early childhood attachment. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 9(1), 53–65.

- Public Health Ontario. (2016). Focus on: Logic models – A planning and evaluation tool. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/eRepository/Focus_On_Logic_Models_2016.pdf

- Pulla, S. (2013). Building on our strengths: Aboriginal youth wellness in Canada’s north. The Conference Board of Canada. http://www.jcsh-cces.ca/upload/14-193_BuildingOurStrengths_CFN_RPT.pdf

- Radu, I. (2018). Land for healing: Developing a First Nations land-based service delivery model. Thunderbird Partnership Foundation. https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Thunderbirdpf-LandforHealing-Document-SQ.pdf

- Radu, I., House, L., & Pashagumskum, E. (2014). Land, life, and knowledge in Chisasibi: Intergenerational healing in the bush. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 86–105.

- Ritchie, S., Wabano, M., Corbiere, R., Restoule, B., Russell, K., & Young, N. (2015). Connecting to the Good Life through outdoor adventure leadership experiences designed for Indigenous youth. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15(4), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1036455

- Robbins, J., & Dewar, J. (2011). Traditional Indigenous approaches to healing and the modern welfare of traditional knowledge, spirituality and lands: A Critical reflection on practices and policies taken from the Canadian Indigenous example. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2011.2.4.2

- Roué, M. (2006). Healing the wounds of school by returning to the land: Cree elders come to the rescue of a lost generation. International Social Science Journal, 58(187), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2006.00596.x

- Rowett, J. (2019). Transformative learning through Etuaptmumk: Piluwitahasuwawsuwakon in counsellor education and practice. [Doctoral dissertation, University of New Brunswick]. UNB Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- Stevens, L. (2005). Cultural camp keeps traditions alive at Blue Quills College. Alberta Sweetgrass, 12(7). https://ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/cultural-camp-keeps-traditions-alive-blue-quills-college-0

- Stuart, C., & Gokiert, M. L. (1990). Child and youth care education for the culturally different student: A Native people’s example. Child and Youth Services, 13(2), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1300/J024v13n02_05

- Sullivan, L., & National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation. (2012). Synopsis of First Nations substance abuse issues developed for use by the RNAO. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. https://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/RNAO-Synopsis-of-First-Nations-Substance-Abuse-Issues-2013-26-09.pdf

- Takano, T. (2005). Connections with the land: Land-skills courses in Igloolik, Nunavut. Ethnography, 6(4), 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138105062472

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

- Urban Aboriginal Knowledge Network. (2016). Guiding ethical principles. https://uakn.org/uakn-guiding-ethical-principles/

- Viswanathan, M., Ammerman, A., Eng, E., Garlehner, G., Lohr, K., Griffith, D., Rhodes, S., Samuel-Hodge, C., Maty, S., Lux, L., Webb, L., Sutton, S., Swinson, T., Jackman, A., & Whitener, L. (2004). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.webharvest.gov/peth04/20041024133950/http://www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/epcsums/cbprsum.pdf

- Waldram, J. (2008). Aboriginal healing in Canada: Studies in therapeutic meaning and practice. Aboriginal Healing Foundation. http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/aboriginal-healing-in-canada.pdf

- Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Oetzel, J., & Minkler, M. (2018). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing health and social equity (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Wildcat, M., McDonald, M., Irlbacher-Fox, S., & Coulthard, G. (2014). Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), i–xv.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Bonding Around the Campfire

Figure 2

Canoe on the Edge of Lake Waiting for Parents and Children

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Contributions of Those Involved in the Project

Table 2

Demographic Data for Family Members