Résumés

Abstract

A research project was implemented through the use of qualitative secondary data analysis to describe a theory of culturally restorative child welfare practice with the application of cultural attachment theory. The research documented 20 years of service practice that promoted Anishinaabe cultural identity and cultural attachment strategies by fostering the natural cultural resiliencies that exist within the Anishinaabe nation. The research brings a suggested methodology to child welfare services for First Nations children; the greater the application of cultural attachment strategies the greater the response to cultural restoration processes within a First Nations community.

Keywords:

- cultural attachment theory,

- culturally restorative practices,

- Anishinaabe

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Culturally restorative child welfare practice is one of the cornerstones for the rebuilding of a nation. For centuries, governmental laws, regulations, policies, and practices have impacted First Nations people, families, and communities. These laws created latent consequences for First Nations people and have resulted in the creation of generations upon generations of social welfare casualties. Child welfare policies have been seen as intrusive and at times culturally inappropriate due to the continued difference between mainstream and Aboriginal worldviews on child welfare practices. A growing body of research has suggested the need to create alternatives that support the recognition of culturally distinctive service practices (Brant, 1990; Rusk-Keltner, 1993) which promote better outcomes for First Nations children. Failure to change policies and regulations on First Nations child welfare practices leads to the over-representation of First Nations children in care across Canada (Blackstock, Trocmé, & Bennett, 2004). Often times, the engagement of family, extended family, and community falls short of the type of intervention needed to rebuild the family system. A consequence of the lack of culturally distinct practices is First Nations children becoming split feathers, a term used to describe the deep loss effects of children displaced from their ancestral roots (Locust, 1998).

Although there have been some self-government gains with the creation of Native child welfare agencies, as with other provincial devolution models, "administrative control over child welfare services to Aboriginal authorities does not mean that the practice orientation will change, as it is still guided by the dominant protection paradigm" (Bellefeuille & Ricks, 2003). As an alternative to this paradigm, the research reviewed 10 historical videos which described the foundational practices of Weechi-it-te-win Family Services. The research, qualitative in nature, documented twenty years of service practices by looking at the theory of restorative child welfare which supports Anishinaabe children's cultural identity and cultural attachment. Weechi-it-te-win Family Services has harmonized and shaped a unique but anomalous service delivery that has protected Anishinaabe children and families in 10 First Nations communities. The research project documented and discussed the unique practices of Weechi-it-te-win Family Services as they support the immediate and longitudinal benefits of children and families of the Rainy Lake Tribal Area.

Weechi-it-te-win Family Services, a transformative agency, has used cultural premises to set a standard of care that can be followed by mainstream social work practitioners when working with First Nations children. The cultural diversity and cultural integrity of Weechi-it-te-win's model allows for the development of standalone Native Child Welfare agencies or First Nations communities to champion their own children according to their own customs and traditions. The fluidity of Weechi-it-te-win's model recognizes that cultural diversity is a necessary component in First Nations communities, as one size will not fit all. Further, the project documented child welfare paradigms and practices through the systematic review of the academic literature, contrasted with Weechi-it-te-win Family Services’ practices.

The research project focused on cultural attachment theory as a mechanism to culturally restorative child welfare practices. Conversely, the literature has shown attachment theory as an approach that has negatively impacted First Nations people who are involved with child protection services. The immediacy of timelines in the promotion of healthy attachment of children with their caregivers is a significant cornerstone of this theory. The research project described how cultural attachment supports and fosters the wellbeing of our children, families, extended families, communities, and nationhood. In the most humble of ways, the research project begins to lay a foundation to support the longitudinal benefits associated with this specific type of care and these specific types of services. It provided options and choices for practitioners to utilize in the creation of positive outcomes and alternatives for First Nations children and families involved with child welfare agencies. Further, the research project introduced standards of care into the literature further to the concepts of cultural identity, cultural attachment theory, and culturally restorative practices as best interest alternatives for First Nations children, families, and communities.

Literature Review

History of First Nations people

Looking at the history of First Nations people is one of the elements to culturally competent social work practice. Throughout the literature, there is a documentation of history in its most negative forms, with minimal research conducted on the inherent resiliencies which have existed for First Nations people. Weaver (2004) stated, "knowledge, skills, and values/attitudes are primary areas that have been identified consistently by scholars as the core of cultural competence with various populations . . . and culture, history, and contemporary realities of Native clients" (p. 30) as a beginning to this process with First Nations people. This means knowing the truth, appreciating, and understanding the history of First Nations people and understanding how this history often brings about strong feelings towards cultural restoration in First Nations communities. Often time, it is painful to look at the history of First Nations people across Canada as it is often based on the realities of ostracism committed by church-and-state on vulnerable populations. This one-sided paradigm of history does not capture the total history of First Nations people, as this recorded history does not typically include First Nations history and cultural norms from a First Nations perspective.

In our understanding of history, we investigate the historical relationship between First Nations people and the policies of church-and-state. But as First Nations people, we are cautioned by our Elders to not stay in the pain of history too long. They teach us to look at the internal strengths of our nations, as it is the cultural laws that have guided how First Nations people govern themselves, their families, and their communities prior the beginning of colonization in 1492. In capturing the full spectrum of history, the positive and the negative, as scholars, there exists the need to capture the essence of First Nations history and the resurgence of culture and teachings. It is the teachings, the language, and the cultural ceremonies that have been passed down from generation to generation, from Elder to Elder, from parent to child. Seeking this knowledge and applying it to current realities is an important aspect of culturally restorative child welfare practice.

Historical trauma

William’s (2006) description of cultural competency through the lens of the critical theory paradigm looked at the outcomes of oppression through historical, political, or economic constructs. In addition, Weaver (1999) stated that in culturally competent social work practice there exists "four important areas of knowledge: 1) diversity, 2) history, 3) culture, and 4) contemporary realities" (p. 220). As we begin to add to our body of knowledge in this area, specifically dissecting the historical implications involved in current realities for First Nations people, practitioners embark on understanding the root of the problems.

In Trans-Generational Transmission of Effects of the Holocaust, Felsen (1998) spoke to the specific characteristics of survivors of the Jewish holocaust. He stated, "Clinical reports suggest special characteristics of children of survivors and particular problems in the relationship between children and parents in survivor families, supporting the hypothesis of intergenerational transmission of Holocaust trauma" (p. 43). He specifically addressed Holocaust offspring as typically having "less differentiation from parents, less feelings of autonomy and independence, elevated anxiety, guilt, depressive experiences, and more difficulty in regulating aggression" (Felsen, 1998, p. 57). Although Felsen's work addressed transmission of intergenerational trauma of Jewish Holocaust survivors, other researchers have extended this philosophy to First Nations, American Indians, or Native American peoples throughout the United States of America and Canada (Duran & Duran, 1995; Duran, Duran, Yellow Horse Brave Heart, & Yellow Horse-Davis, 1998; Morrissette, 1994; Yellow Horse Brave Heart, 2003).

Morrissette (1994) discussed the holocaust of First Nations people and specifically discussed the residential schools and how this genocidal experience continues to haunt First Nations people. Yellow Horse Brave Heart (2003) had a significant amount of research related to historical trauma, historical trauma response, and psychoeducational programs with the historical trauma in First Nations communities, specifically the Lakota Nation. She defined historical trauma as "the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences" (p. 7). She described historical trauma response as:

the constellation of features in reaction to this trauma, and that [historical trauma] and [historical trauma response] are critical concepts for native people, as increasing understanding of these phenomena, and their intergenerational transmission, should facilitate preventing or limiting their transfer to subsequent generations

p. 7

In their article Healing the American Indian Soul Wound, Duran et al. (1998) discussed the implications of First Nations traumatic history and the connection to the soul wound otherwise described by other researchers as "historical trauma, historical legacy, American Indian Holocaust, [and] intergenerational post-traumatic stress disorder" (Duran et al., 1998, p. 341). The researchers go on to define elements of historical trauma as:

features associated with depression, suicide ideation and behavior, guilt and concern about betraying the ancestors for being excluded from suffering as well as obligation to share in the ancestral pain, a sense of being obliged to take care of and being responsible for survivor parents, identification with parental suffering and a compulsion to compensate for the genocidal legacy, persecutory, and intrusive Holocaust, as well as grandiose fantasies dreams, images, and a perception the world is dangerous

Duran et al., 1998, p. 342

In addition to these characteristics, Duran et al. (1998) stated these emotional calamities are triggered by enduring acculturative stress. This acculturative stress is the result of history or historical legacy and latent consequences of laws and policies meant to help First Nations people.

The link between history and contemporary issues for First Nations people is apparent.

The past 500 years have been devastating to our communities; the effects of this systematic genocide are currently being felt by our people. The effects of the genocide are quickly personalized and pathologized by our profession via the diagnosing and labelling tools designed for their purpose (Duran et al., 1995).

Utilizing culturally competent strategies to effectively deal with "grief resolution and healing from historical trauma response" (Duran et al., 1998) has become an efficient clinical response. Further, psycho-educational programs on historical trauma, a process of disclosure within a group setting or in cultural ceremonies, in addition to ceremonial grieving processes to promote community wellness and cohesiveness, are all strategies used by Brave Heart (1998). The omission of historical trauma as a frame of reference for the social work profession is a gross injustice for First Nations people, as the disregard of history and its impact on current realities is, by definition, to continue culturally destructive practices.

Canadian profile

A profile of First Nations people has been captured by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) (AFN, 2007a). Today, there are a total of 633 First Nations communities across Canada with an estimated population of 756,700 First Nations members (AFN, 2007a). The AFN stated that the most pressing problem that exists is the overall economic disparity between Canadians and First Nations communities. One instrument that shows this disparity is the Human Development Index. "First Nation communities are ranked 76th out of 174 Nations when using the United Nations Development Index 2001. This is compared to Canadian communities who ranked 8th" (AFN, 2007a, p. 3).

First Nations people in Canada continue to be challenged and faced with their children being culturally displaced, uprooted from their identity, and natural cultural resiliencies that exist within the First Nations continuum of care. An epidemic of Native children being placed in foster care systems throughout Canada is a growing concern for First Nations people. According to the AFN (2007b), "1 in 4 First Nations children live in poverty, compared to 1 in 6 Canadian children" (p. 2), furthermore, "as many as 27,000 First Nation children are currently under care" (p.2). The Canadian Incident Study on Reported Child Maltreatment is one current national study that has documented the over-representation of First Nations children in care across Canada (Trocmé, Knoke, & Blackstock, 2004). This research identified a total of "76,000 children and youth placed in out-of-home care in Canada, 40 percent of those children are Aboriginal or children labelled ‘Indian’ or ‘Native American,’ yet fewer than 5% of the children in Canada are Aboriginal" (Trocmé et al., 2004, p. 2). In some provinces, 80 percent of the children in out-of-home placements are of First Nations descent (Trocmé et al., 2004). Blackstock et al. (2004) stated, "at every decision point in cases, Aboriginal children are over-represented; investigations are more likely to be substantiated, cases are more likely to be kept open for ongoing services, and children are more likely to be placed in out-of-home care" (p. l). The national research has indicated an "overrepresentation due to poverty, unstable housing, and alcohol abuse complicated by the experience of colonization" (Blackstock et al., 2004, p. 14). In light of this knowledge, it is a vital indication of the need to re-evaluate mainstream child welfare practices with First Nations people.

Child welfare laws and implications for First Nations people

First Nations people and social work advocates have a professional responsibility to change how laws, policies, and frameworks influence our people. There are numerous laws, policies, and regulations that have impacted First Nations people, so much so that First Nations communities are typically marginalized and collectively oppressed. There are two main destructive areas of policies, the first being the residential school policies and the second being child welfare policies and laws. Comeau and Santin (1995) stated, "in no other area did federal bureaucrats and professional social workers wreak so much havoc in so little time as in the field of child welfare" (p. 141). In the best interest of children, judges, lawyers, and professional social workers dictated "the loss of an entire generation of children" (Comeau & Santin, 1995, p. 141). Patrick Johnston (as cited in Comeau & Santin, 1995), the author of Native Children and the Child Welfare System, called this era the "sixties scoop" (p. 143). Comeau and Santin (1995) described the amendments to the Indian Act in 1951 where the federal government gave provincial governments the jurisdiction to provide child welfare services on First Nations communities, thereby washing their hands of their fiduciary responsibility to First Nations child welfare initiatives. Further, "by 1980, 4.6% of all registered Indian children were in care across Canada, compared to less than 1 % of all Canadian children" (p. 143). In addition to this statistic, during the 1970s and 1980s, cross-cultural placements were used as the primary modus operandi to adoption (Comeau & Santin, 1995). "In 1985, Edwin C. Kimelman, Associate Chief Judge of the Manitoba Family Court reported on Native adoptions and foster placements and described the situation as the routine and systematized ‘cultural genocide’ of Indian people" (Comeau & Santin, 1995, p. 145). The child welfare paradigm in Canada does not include culturally restorative practices as a standard of care for First Nations children.

Implications of attachment theory

Bowlby, the father of attachment theory, built on components of Freud's theory, hypothesizing an infant's need to explore, for safety, and for security with the help of a significant caregiver (Waters & Cummings, 2000). Bowlby further hypothesized attachment as control systems or behavioural systems that are driven and shaped by evolutionary theory. Two major themes in Bowlby's work evolved: a) a secured base concept and b) working models (Waters & Cummings, 2000). In their critical analysis of attachment theory, Waters and Cummings (2000) suggested a need to have a criterion of application for review across cultures as it can erode the scientific consistency needed to maintain the theory. Further, they stated,

Bowlby's emphasis on the early phase of attachment development has been a source of misunderstanding and missed opportunity - misunderstanding because it suggests that secure base behaviours emerges rather quickly and missed opportunities because it doesn't direct attention to the maintaining and shaping influence of caregiver behaviour or developmental changes in secure base use beyond infancy, much less in the course of adult-adult relationships

p. 166

Waters and Cummings (2000) discussed the lifespan of a child into adulthood and point out the gap in between the life stages as being unknown; therefore, they suggest it is necessary to continue to develop "the effects of early experiences, the mechanism underlying stability and change, and the relevance of ordinary socialization processes in attachment development" (p. 166).

In child welfare practice:

The primary goals of child welfare and mental health professionals serving these maltreated children are to ensure their safety and protect them from further abuse, to help them heal from any physical or psychological effects of the maltreatment, and to provide opportunities for them to become healthier and well-functioning children and adults

Mennen & O'Keefe, 2005, p. 577

Often permanency philosophies and timelines in child welfare have been guided by attachment theory. Timelines for securing change within the family systems do not allow for adequate time to change the individual, family, and, at times, the community. First Nations children and families often fall victims to the misapplication of attachment theory. A child welfare practitioner’s competing interest, noted by Mennen and O'Keefe (2005), is that:

Child welfare policy strives to use children's attachments as a guide to decisions about placements, but the demands of the system can interfere with this ideal. Increased caseloads, poorly trained workers, media attention, and political pressure often combine to lead to decisions that are not in children's best interest

p. 578

Often times, attachment theory's link to suggested long term psychological issues, maladjusted members of society, or links to behavioural issues in relation to societal safety have also been key factors in decisions of attachment and permanency planning in child welfare management. Berry, Barrowclough, and Wearden (2006) stated:

Attachment theory has the potential to provide a useful theoretical framework for conceptualizing the influence of social cognitive, interpersonal, and affective factors on the development and course of psychosis, thus, integrating and enhancing current psychological models. Insights derived from attachment theory have significant clinical implications, in terms of informing both psychological formulations and interventions with individuals with specific types of insecure attachment

p. 472

Mennen and O'Keefe’s (2005) study had hypothesized that problematic behaviours are associated with a lack of immediate attachment to a significant caregiver.

Unfortunately, the research on attachment behaviour of children in foster care is limited and needs to be bolstered to provide a clearer understanding of how maltreatment, separation from parents, and placement in foster care influences attachment and how foster children's attachment affect their long-term adjustment

p. 582

It is important to note, there is a minimal amount of academic research on cultural attachment requirements related to either a generalist approach to service delivery or a more specific approach like working cultural attachment models specific to First Nations communities. The complete disregard to elements of cultural competency, historical implications, and latent consequences of policies on First Nations people is evident in the literature. A defined culturally congruent child welfare service practice model is minimal, if not nonexistent in the research. Currently, there exists a deficiency on culturally-specific research on First Nations children and statistics continue to show a gross over-representation of First Nations children in care across Canada.

Cultural competency

Cultural competency in the field of human services has been the intention for many practitioners but it is seldom realized. There are many reasons that have contributed to this dilemma. The incorporation of ethical standards and principles as it relates to culturally competent social work practice, in addition to a growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of cultural competence, has not brought the direction and clarity that is needed to embrace such a criterion (Weaver, 2004; Williams, 2006). In addition to this predicament, the concept of cultural competence through the literature has not navigated one true path to the attainment of these standards and principles. The presence of ambiguity as it relates to defining cultural competency has left many practitioners with minimal tools to effectively and efficiently deal with clients in a manner that is conducive to the client's cultural orientation and framework (Williams, 2006). As the literature has shown, there is a growing trend to further cultural competence strategies but there is "little empirical work to provide professionals with specific principles or procedures for effective cross-cultural work" (Weaver, 2004, p. 21). In particular, with specific cultural groups such as the Anishinaabe Nation.

Culture has been defined in many different books, literature, journals, magazines, and dictionaries. Cross (2006) defined culture as "the integrated pattern of human behaviour that includes thought, communication, action, beliefs, values, and institutions of a racial-ethnic, religious, or social group" (p. 1). Day (2000) defined cultural epistemology as the "language and communication patterns, family, healing beliefs and practices, religion, art/dance/music, diet/food, recreation, clothing, history, social status, social group interactions, and values." Hogan (2007) stated that culture is learned, shared, and transmitted values, beliefs, norms and lifeways of a group which are generally transmitted intergenerationally and influence one's thinking and action. Supplementary to this definition is the beliefs, the arts, the laws, morals, customs, or values which make up the societal structure of a nation (Hogan, 2005).

Williams (2006) stated:

Culture defines the norms, symbols, and behaviours that aid us in making sense of the world. When there are gaps among service systems, practitioners, and clients, it contributes to misunderstandings and impasses that prevent effective social work intervention; seeking cultural competence is our response to that dilemma

p. 210

Cultural competency suggests having some level, standard, or quality of understanding in working with another culture. This requires the act of acquiring knowledge and skills to meet the needs of the clients. Siegel et al. (2000) defined cultural competency as "the set of behaviors, attitudes, and skills, policies and procedures that come together in a system of agency or individuals to enable mental health caregivers to work effectively and efficiently in cross/multicultural situations" (p. 92). Cross (2006) provided a similar definition of cultural competence: "a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or professional and enable that system, agency, or professional to work effectively in cross-cultural situations" (p. 1). Williams (2006) stated that "cultural competencies often are organized into categories for self-awareness, attitudes, skills, and knowledge" (p. 210). Cultural competence requires the:

systematic gathering of cultural information . . . on beliefs, practices, and characteristics of different ethnocultural groups . . . , generic social work skills . . . , and competencies include self-awareness . . . , analysis of power structure . . . , empowerment . . . , critical thinking . . . , and development of an effective working alliance

Williams, 2006, p. 211

Cultural competence at an organizational level has been identified within the literature. In this analysis, there exists a range of subjective organization evaluations and quality assurance indicators. Cross (2006) identified a cultural competency continuum ranging from cultural proficiency to cultural destructiveness. This continuum included cultural destructiveness, cultural incapacity, cultural blindness, cultural pre-competence, basic competence, and advance cultural competence. Other research has shown performance measures and quality assurance mechanisms have been developed to evaluate the concept of culturally competent practices. Siegel et al. (2000) identified six domains: “needs assessment, information exchange, services, human resources, policies and procedures, and outcomes” (p. 95). In addition, the model described by Siegel et al. (2004) evaluates each domain on three different organizational levels: administrative, provider network, and individual. Each domain and each level have outcomes indicators to evaluate the effectiveness of culturally competent service delivery. All discussions on cultural competency at an organizational level are important, as it is in the system that defines its policy, procedures, and direct service practice with client groupings.

Although definitions and descriptions of culture and cultural competence are extensive and do not, by themselves, help practitioners attain competence, the literature has defined culture as the holistic make-up of a people and the act of competent service practice is the acknowledgement and inclusion of culture into all levels of social practice with people. The manner in which we incorporate service standards into accountable organizational frameworks is the threshold of cultural competence within any service organization.

The mandate of Weechi-it-te-win Family Services

Weechi-it-te-win Family Services (WFS) is a Native child welfare agency in Fort Frances, Ontario, Canada. WFS was established to create a change in the mainstream child welfare practice in Indian communities. The agency’s services have evolved considerably over the last twenty years. The growth of the agency has been referred to as the iceberg phenomena (Simard, 1995) and is a symbol used to show the thaw of distrust for mainstream child welfare agencies. WFS became an Aboriginal Children’s Aid Society on September 2, 1987, under the Ontario Child and Family Services Act. As a society, WFS has jurisdiction for services respecting the welfare of children and their families within ten First Nations communities (Ferris, Simard, Simard, & Ramdat 2005).

WFS began as a vision for a child and family services agency based on Anishinaabe customs and values. A Native model of child welfare called the Rainy Lake Community Care Program was developed based on the goals adopted by the Council of Chiefs. Namely, “to preserve Indian culture and identity among our people; to strengthen and maintain Indian families and communities; and to assure the growth, support, and development of all our children within Indian families and communities” (Ferris et al., 2005, p. 5). Since its inception, WFS has endeavoured to provide child protection and family support services in ways that promote the preservation of Anishinaabe culture and identity, strengthen Anishinaabe families and communities, and foster growth and development of Anishinaabe children within Anishinaabe families and communities. It is believed that the spirit of cultural development for the agency is deeply rooted in the traditional laws and customs of the Anishinaabe Nation.

The elders have advised and informed [WFS] that the agency has Cultural Rites as an Aboriginal Organization. The Cultural Rites arise from the fact that the Agency was born from Aboriginal aspirations and determination and, as such, was bestowed a Name and Ishoonun. In accordance to Aboriginal cultural thought, the Agency’s Name came from the Atisookaanug as well as the emblem of the loon. The loon has provided numerous instructions to WFS on how the organization needs to operate and perform. Later, WFS was bestowed pipe(s), flag(s), a drum, and medicines. Because of these sacred items, WFS has a duty to ensure that they are treated in a cultural manner that respects the original instructions from the Elders or ceremony that transferred these items to WFS. In addition to the Aboriginal cultural thought, the moment WFS received its Name it became more than a simple organization that provides services, it, in fact, became customarily personified in the eyes of the Atisookaanug. This means that WFS became a person (much like the idea of a corporation under the Corporate Act), a living and breathing Aboriginal entity with a customary responsibility for family and cultural preservation

WFS, 2005, p. 2

Instrumental to culturally competent strategies utilized within an agency system, it is imperative for every area of structures and services to integrate the cultural make-up or teachings of the community they serve. This is more than including culture as an afterthought; the culture must be the foundation for the agency’s structure.

Models of culturally restorative child welfare practices

Limited information on culturally restorative child welfare practice has been found in the literature; however, many best practice models on First Nations child welfare practices are alive and well throughout Canada and abroad. The integration of cultural frameworks into service practice is not new, as First Nations child welfare or children's mental health agencies have been advocating for this type of practice for decades. As key First Nations stakeholders and First Nations service providers enter the world of academia, a forum for change in service delivery paradigms grows. It is essential to continue to address these in a manner that creates cultural understanding, values diversity, and supports culturally restorative child welfare practices. In the spirit of the transfer of knowledge, the researchers must:

utilize the research initiatives of the world of academia, with the same vigour, but [apply] this research vigour to our cultural teachings of their Nationhood, and what a world of difference we would make for our children and our grandchildren to come

Tibasonaqwat Kinew, 2006

Cultural identity

Cultural identity formation is an important aspect of cultural restoration processes. The literature advised careful reflection and critical analysis of the frame of reference in the presenting of the definitions of cultural identity for First Nations people (Oetting, Swaim, & Chairella, 1998; Peroff, 1997; Weaver, 2001). Oetting et al. (1998) discussed how identity changes over time and the manner in which we define and evaluate cultural identification changes with time as well. Weaver and Yellow Horse Brave Heart (1999) stated, "Little is taught about how to assess where the client is in terms of cultural identity" (p. 20). Adding to the confusion about cultural identity is that cultural identity has been defined "from a non-Native perspective. This raises questions about authenticity: Who decides who is an indigenous person, Native or non-Native? The federal government has asserted a shaping force in Indigenous identity by defining both Native nations and individuals" (Weaver, 2001, p. 245). In his article, Indian Identity, Peroff (1997) stated, "Far more than with any other American racial or ethnic minority, American Indian identity or 'Indianness,' is often expressed as a measurable or quantifiable entity" (p. 485). The example of this measurement given for the United States of America is the blood quantum. In Canada, this is also true for First Nations people as well and is defined as eligible for status, non-status, Métis, or Inuit. Weaver (2001) discussed the pitfalls of defining cultural identity and stated, "Identity is always based on power and exclusion. Someone must be excluded from a particular identity in order for it to be meaningful . . . and to search for the right criteria is both counterproductive and damaging" (p. 245). The literature goes on into several key areas: definitions of cultural identity from an Indigenous perspective; a discussion on the themes of cultural traditions and revitalization; measurements of cultural identity (Novins, Bechtold, Sack, Thompson, Carter, & Manson, 1997; Oetting et al., 1998; Peroff, 1997; Weaver, 1996; Weaver, 2001; Weaver & Yellow Horse Brave Heart, 1999); historical implications related to cultural identity; and the adoption of culturally restorative strategies into child welfare practices.

The concepts of cultural identity, cultural assessment, cultural attachment, cultural revitalization, and individual/collective renewal are documented in the literature (Peroff, 1997; Weaver, 1996; Weaver, 2001; Weaver & Yellow Horse Brave Heart, 1999). Cultural identity is defined by Oetting et al. (1998) as the connection to a particular group due to "qualified classifications" (p. 132), or likeness that is "derived from an ongoing social learning process involving the person's interaction with the culture." (p. 132). Further, "cultural identification is related to involvement in cultural activities, to living as a member of and having a stake in the culture, and to the presence of relevant cultural reinforcements that lead to perceived success in the culture" (132). Oetting et al. (1998) also discussed the importance of family, extended family, and community in the transmission of this cultural knowledge. Peroff (1997) discussed the concept of tribe or community identification and stated, "An Indian identity is the internal spark that sustains a living Indian community" (p. 491).

Weaver (2001) discussed cultural identity in three domains: "self-identification, community identification, and external identification" (p. 240). She defined cultural identification as being based on "a common origin or shared characteristics with another person, group, or ideal leading to solidarity and allegiance" (p. 241). She stated, "Identities do not exist before they are constructed . . . and are shaped in part by recognition, absence of recognition, or misrecognition by other" (p. 241). Further, identity is "multilayered, (and may include) sub-tribal identification like clan affiliations, tribes or regions, descent, or lineage" (242). Weaver discussed how "self-perception is a key component of identity . . . , identity is not static rather it progresses through developmental stages during which an individual has a changing sense of who he or she is, perhaps leading to a rediscovered sense of being Native" (p. 243). She also suggested that as the individual ages, the cultural formations become stronger (Weaver, 2001).

There is a history of cultural identification assessments that begins with a mainstream worldview. Often times, these models look negatively at other worldviews and compare levels of assimilation or acculturation into that mainstream worldview (Weaver, 1996). Weaver (1996) discussed these models of assessment: transitional models, alienation models, and multidimensional models of assessment on a continuum ranging on levels of cultural competence. The most current model of cultural identification assessment is the orthogonal cultural identification model (Oetting & Beauvais, 1998; Weaver, 1996). Further to this type of assessment, the world of psychology has also implemented cultural assessment into their supportive documentation relevant to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders assessments (Novins et al., 1997). One of the mechanisms to achieve this goal was the development of an outline for cultural formation, the importance of the child's family system in the course of therapeutic treatment, and overall cultural identity formation (Novins et al., 1997).

Historical implications on cultural identity have also been described in the literature (Weaver, 1996; Weaver et al., 1999). The pattern of laws, policies, and regulations dictated on First Nations people had, and continues to have, dire impacts on First Nations people. Weaver et al. (1999) stated,

When assessing Native clients, social workers should explore the relevance of historical trauma . . . , discuss multi-generational trauma experienced by a client's family and nation . . . , and recognize the trauma, then take the steps towards a recognizing and dealing with and healing that trauma is critical

p. 29

Social workers must begin to utilize multi-generational genograms to support the exploration of collective trauma experience in nationhood, in the community, in the extended family, and with family. It is important to caution social workers of possible misconceptions as historical trauma has often been used as a backdrop to permanency planning. This, of course, would be a gross error in cultural identity assessment as it would perpetuate a system that has existed for centuries.

The federal government's attempt to deal with the “Indian problem” has led to a pattern of defining identity "based on the statistical extermination of Indigenous people, thereby leading to an end to treaty and trust responsibilities" (Weaver, 2001, p. 247). As a result, cultural identity should encapsulate a holistic view based on self-perception, self-identification, self-in-relations to family, community, nationhood, and other nations under different tribal affiliations. Further, identity development is a fluid system, evolving with time and nurturance. The beauty of cultural identity is eloquently captured in this quote:

The strength of the culture is so powerful and is embedded in the very nature of our existences, that even if all systematic oppression work and there was no ounce of culture left in us as a people and the only thing noticeable about us as different would be the colour of our skin . . . the culture is so strong that one day someone would dream . . . and we as a nation would start over once again

Kelly, 2007

Methods

The research captured the knowledge and experience associated with the longitudinal development of an "Indian alternative" at WFS. It was designed to address the question: What is culturally restorative child welfare practice? The researcher looked at ten, one-to-one qualitative video footage of thirty minutes each, which have existed within the agency as a part of curriculum development data archives. These data sets are a part of on-going training and curriculum development projects of WFS and are part of the descriptive analysis of culturally restorative child welfare practice. The research was consistent with secondary data analysis that was guided by qualitative examination.

Results

WFS is an agency that has developed a solid culturally competent social work practice. The WFS model of governance has pre-disposed a concept of collaboration with Elders, tribal leaders, and grassroots community members. As a result of oral tradition, they have been taught the concepts of culturally competent and congruent social work practice through an inductive learning style. The invaluable resources within the First Nations have been available to educate workers on cultural awareness/sensitivity for child welfare and children's mental health services whose main population is the ten First Nations communities of WFS. As a result of this collaborative effort, cultural attachment theory has been re-vitalized, developed, and fostered by the people of WFS. This model has shown the importance of cultural restoration when working with First Nations populations, based on ethical considerations, effective practice, evidence-based practice, and cultural skill development.

In a review of the data, it is clear to state the existence of the concept of wiiji'ittiwin before WFS became a corporate structure. The Anishinaabe concept of wiiji'ittiwin is difficult to translate, as most often the English language does not adequately equate to the true meaning of the word. Within the Anishinaabe language, there are systems, structures, meanings, teachings, legends, roles, responsibilities, and, often times, ceremonies attached with that Anishinaabe translation. Many of these concepts of attachment within the Anishinaabe language is embedded with the understanding that the language is the heart of the people and carried in the very genetic structure of the Anishinaabe people. This review of the data and its presentation is based on the theoretical principles of establishing the rationale, revitalizing the teachings, and showing a mechanism to do so within the concept of wiiji'ittiwin – helping and supporting children and families.

Historical context

The historical context of WFS begins with the understanding of family structures that existed before colonization and is the main focus of much of the results within the research. Colonization, historical traumas, and impacts are latent consequences and present-day realities that have touched Canada, Ontario, and the Northwestern part of Ontario in the Rainy River District. A consistent theme that has been documented is the ramifications of federal and provincial laws on child welfare practices in Canada that have seriously injured First Nations people in the Rainy River District. The First Nations population within the Rainy River District was an estimated 10% of the total population in the early 1960s. As much as 80% of the children in care were First Nations children with the social services agencies of the time, clearly indicating the over-representation of First Nations children in care during that era. Some underlying factors that contributed to this fact were the absence of Anishinaabe child welfare and/or the acknowledgment of the existence of Anishinaabe child welfare systems. Often times, the community standards were compared with mainstream practices. This was interlaced with the First Nations’ multigenerational pain as a result of the despairing poverty, residential school trauma and 60s scoop losses. As a result, mainstream social welfare and child welfare agencies were mandated by the provincial government to deliver these services on behalf of the federal government. The problem that existed within the Rainy River District was a mainstream agency delivering services to First Nations people with the absences of cultural understanding or context. As a result, children were often removed from their homes, placed in non-Native homes, displaced from their communities, often times losing their identity as Anishinaabe, and thereby suffering a loss of attachment to the resiliency that exists within the Anishinaabe culture. WFS was created as a response to the paradigm that existed during this point-in-time within the Rainy River District.

Throughout the years, the research has shown the absence in a cultural context or cultural continuity, which had significant impacts on attachment to culture. Mass or generational removals of children in the First Nations communities began to erode the natural resiliencies that existed within the First Nations communities. The attitudes of mainstream workers were laced with an ethnocentric view that allowed the systematic oppression of a population. One of the interviewers stated, "Workers did what they thought was best . . . government did what they thought was best . . . but in practice, they fell short of long term implications related to short-sighted practice" (WFS, 1984a). He went on to say, "Ignorant practice resulted in gross patterns of injustice for First Nation children, families, and communities" (WFS, 1984a). The mainstream system focused narrowly on child safety, removal, foster care placements, and adoption. This streamlined approach often did not engage the family, extended family, or community. As a result of these minimal competencies in cross-cultural relationships, there was a severance of family, extended family, and community. Often times, this left a wreckage of victimization and trauma due to the application of European standards and intervention on First Nations people.

The research indicated there was not a blanket acceptance by First Nations people of the child welfare paradigm in the early 1950s to 1985, which was a system based on coercion. For those that were taken from their families and communities during this era, it is important to understand the worldview of the time. It was an era of history based on extreme violence. Elders discussed the trauma being "so shocking to a people and a culture that it was often not talked about" (Tibasonaqwat Kinew, 2006). Another Elder talked about the fight being taken out of them through years and years of government interventions and churches who tried to convert the tribal people. Community members, through their family systems, disclosed the history of Jesuits and Royal Canadian Mounted Police terrorizing people and cultures. As a result, there was often conversion to "mainstream ways" through trauma and threats. The research indicated laws and policies were put in place to disrupt the natural Anishinaabe systems. These included values, worldviews, standards, and systems put in place for First Nations people only to eventually collide with each other, as often two worldviews do. It was in the early 1960s when advocates began to plead with social workers in the Rainy River District to begin to look at them as human beings; to deal with Natives with some compassion and to allow for child welfare governance to take place in the First Nations communities. It was always the intent of these advocates to re-establish tribal jurisdiction. Two key government position documents lead way to the development of the WFS: A Starving Man Doesn’t Argue (Technical Assistance and Planning Associates, 1979) and To Preserve and Protect (Unknown Author, 1983). Both government policy position papers discussed the ramifications of child welfare practice and the encouragement of First Nations child welfare jurisdiction in the First Nations communities.

A response to the paradigm of the time resulted in an assertion of tribal sovereignty across the Rainy River District. Examples ranged from First Nations roadblocks to the guarding of tribal lands to ensure children would not be taken away by the Children’s Aid Society. Men like Moses Tom and Joseph Big George are credited with the community initiatives across the territory, Ontario, and other provinces in Canada. Their commitment as tribal leaders to empower Anishinaabe child welfare systems was core to the development of WFS, but also core to the steadfast vision of saving First Nations children from the clutches of mainstream child welfare agencies and their systematic strategies to “take the Indian out of the child.” The assertion of tribal control over child welfare is a consistent theme that has been voiced from the beginning and continues to be a driving theme across the decades. The politic lead by Parent/Teacher Organizations across Ontario began to open discussions with the government to promote alternatives to child welfare. The value of commitment to these strategies has been passed on from generation to generation. This is seen through the political and community movement to promote the inherent strategies that exist within the Anishinaabe culture. For WFS, it is consistent in the tribal sovereignty development of the agency. This is clearly seen in the following timeline of policy development:

The 1970s: the prevention programs in each of the ten First Nations communities;

1985: the planning committee designed to create the foundation of WFS and the community care program’s vision, mission, goals, and objectives;

1986: society status is attained by WFS;

1990: cultural competency strategies were documented into bylaws, policies, and service practices;

2000: the beginning of the devolution process for WFS; and

2005: WFS implemented Naaniigan Abiinooji as a best interest strategy for children of WFS.

As an agency of national interest for the territorial nation of Treaty #3, WFS is responsible for a restorative approach to child welfare. They do not condone or blindly accept the rapid child welfare changes under the Child and Family Services Act or its amendments. The role of WFS is to be a resource to the communities as they rebuild their communities’ natural structures and protect the communities from the continual distortion and exploitation of power exerted on First Nations people. Further, WFS is true to the understanding “that the Native people have been a persecuted minority with the need to regain and resume their collective role in the raising of their children” (WFS, 1984a).

The research themes have shown that there has always existed a need to change the policies but the government failed to acknowledge cultural wisdom, often believing it had no place in modern day First Nations communities. It was important in the development of WFS for it not to repeat the same pattern. As a result, there existed another important theme of a spiritual timeline in which cultural precepts, ceremonies, drums, and pipes were given to the agency, along with the responsibility and duty of care for these items on behalf of the children, families, and communities. These items are noted throughout the research as the heart of the agency’s vision and spirit. With the cultural foundation and spiritual acknowledgement in place, WFS began to embark on a spiritual journey of cultural restoration into child welfare practice. This practice has great importance as it has allowed for the collective responsibility of raising a child with instilling values, traditions, roles, and responsibilities of the First Nations community. Further, it allowed for the opportunity to safeguard the child’s inherent cultural identity and dignity related to the knowledge of one’s purpose and place within the cultural context of Anishinaabe mino-bimaatiziwin.

Culturally restorative child welfare practice

Cultural restoration is the rebuilding of a nation of people based on Anishinaabe teachings, language, principles, and structures. It is based in the fierce love of Anishinaabe people for their children and the creative thinking that has allowed for the creation and harmonization of strategies to empower Anishinaabe Naaniigan Abiinooji – Anishinaabe child welfare. It is the steadfast vision of the traditional governance structure and the First Nations advocates that have led the way to the creation of this system of care. Cultural restoration uses the concepts involved in the Naaniggan Abiinooji’s Anishinaabe Natural Protective Network Principle. Some of these include principles of customary care, the best interest of the child, identity, developmental milestones, cultural placement, definitions of family, Anishinaabe rights of the child, cultural ceremony, and Anishinaabemowin – the language of the people to achieve this feat. All of these factors are the mechanisms of cultural attachment theory to achieve cultural restoration.

Throughout the research, the project has suggested that the greater the application of cultural attachment strategies, the greater the response to cultural restoration processes within a First Nations community. This directly proportional proposition suggests an alternative strategy to governmental engagement with First Nations people, which are based on reinvestment in cultural attachment strategies in First Nations communities. Cultural presence in First Nations communities equates to increased trust and more access to services, thereby bolstering higher caseloads – the iceberg phenomenon. The research has indicated a continual battle to justify the needs to alter programs and services for the betterment of First Nations communities. This continues to be a source of frustration described throughout the research.

Emerging Anishinaabe values in the Community Care Programs has stated,

Children represent the future and the future cannot be entrusted to the care of external government and public agencies. Reaffirming Anishinaabe identity requires control over community life and [the] preservation of Anishinaabe identity requires control over the care and protection of children

Simard, 2006

The laws of the Anishinaabe are from the Creator and are thereby sacred. They have meaning, creating a bond and attachment to the expectation of the Creator for individuals, as Anishinaabe. These laws come with traditional customary obligations, known by the Anishinaabe. The research has also indicated that the Anishinaabe Nation was once a thriving nation that took care of everyone and continues to be a proud people and nation. Collective responsibility and/or sacred responsibility were taken seriously. This is to be passed down from generation to generation via the oral teachings, birch barks scrolls, language, pictographs, rock paintings, and the petro-graphs found throughout Turtle Island (Jourdain, 2006).

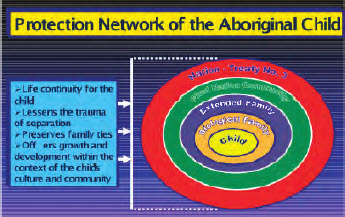

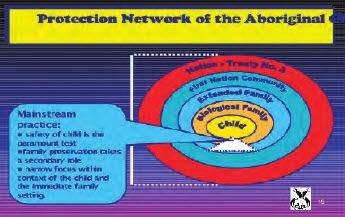

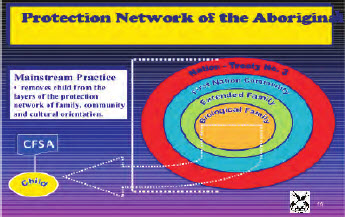

The natural protective factors are the systematic structure which has existed in within the Anishinaabe teachings for a millennium. The structure acknowledges the protective factors, the system needed to be in place, and the roles and the responsibilities of the people within the circles (Appendix 1). It shows the natural multifaceted and collective approach to raising a child. The approach acknowledges the importance of continuity for the child, the development of identity, the character, and the responsibility attached to children in their role within the Anishinaabe society. Within WFS training presentations, they have contrasted their approach with the mainstream approach as it relates to First Nations families, extended families, First Nations communities, and the Anishinaabe Nation.

As the previous documentation of history and the literature review have shown, the narrow approaches used by mainstream practices often fall short, thereby creating greater destruction to community restoration and child safety. A key piece noted by the research is "family preservation takes a secondary role within mainstream social work practice" (Simard, 2006). Further, the research has shown the child being ripped out of their inherent Anishinaabe family system and support structure. This, of course, is the crux of the problem as it does not allow for continuity and restoration of Anishinaabe teachings and systems to take responsibility and accountability for raising their own.

The conceptual basis of the research is centred on the protective layers within the Anishinaabe society. The center of the protective layer is the child. The teachings related to the child begin with the Anishinaabe Rights of the Child Principle. The Anishinaabe Rights of the Child Principle was based on the teachings of the Anishinaabe; however, it was researched and documented by Jourdain (2006) in the early 1990s. It consists of the following:

Spiritual name: Anishinaabe ishinikassowin

Clan: ododemun

Identity: anishinabewin

Language: anishinabemoowin

Cultural and healing ways: anishinabe miinigoosiwin

Good life: minobimatiziwin

Land: anishinabe akiing

Lifestye: anishinabechigewin

Education: kinamaatiwin

Protection: shawentassoowin and ganawentasoowin

Family: gutsiimug

Jourdain, 2006

The Anishinaabe Rights of the Child Principle are consistent with an ethical assumption which links to concepts and laws in Naaniigan Abiinooji. It is meant to ensure a child has the spiritual foundation of inode'iziwin and the ability to balance their lives to achieve minobiimaatiziwin within their surroundings. This principle allows for the formation of identity within the context of Naaniigan Abiinooji and is the best practice related to the raising of an Anishinaabe child. It is used as a mechanism to provide an opportunity for the child, family, extended family, and community to collectively raise the child within the child's cultural context.

Identity is an important factor for Anishinaabe, although there are many concepts and meanings which define identity. As shown in the literature review, Anishinaabe describes identity as a living and breathing force. It is a special link between a child and the Creator; it is not static and will not end. The concept is difficult to describe, but the Anishinaabe word is Daatisookaanug – my spirit/my identity – and is similar to Atisookaanug, which is of the spirit or the sum of the spirit. Atisookaanug is the all-knowing and, some might say, direct link to the Creator. The connection of identity to Anishinaabe is carried within the spirit and it is the spirit that brings strength, love, ancestral knowledge, and a mode of being on Turtle Island. In Anishinaabe, we are of the spirit and it is this connection of restoration which will rebuild a child, a family, a community, and a nation of people.

Further to the concept of Anishinaabe Rights of the Child Principle, is the concept related to the Anishinaabe Developmental Milestones Principle within practice. As in European principles on development, Anishinaabe have consistent teachings on Anishinaabe cultural milestones. If one researches the developmental milestones of a culture, there are overarching similarities. The Elders have discussed these concepts and some Anishinaabe have written and discussed this as a manner of introduction into the WFS service practices.

Jourdain (2006) has captured and discussed the Elders’ teachings on the Four Hills of Life, which are a teaching of the Anishinaabe society with an emphasis on the importance of cultural responsibilities related to the raising of a child. Jourdain (2006) discussed the traditional lifespan of the Anishinaabe and the unique healing component of achieving the psycho-spiritual task associated with each level. The levels are: "Abinodjiiwin - childhood; Oshkinigiwin - youth hood; Nitawigiwin - Adulthood; and lastly Kitisiwin - elderhood" (Jourdain, 2006). Jourdain also pointed out the tasks associated with each life stage. Abinodjiiwin is the time to develop the child identity, a time to develop trust, and a time to make connections within the community. In Oshkinigiwin, it is a time of understanding the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual needs related to one's own being. It is a time in which one child would go to fast and receive his/her vision related to their purpose. It is also a time in which the family would begin to prepare the young person to become a fully functioning adult within the Anishinaabe society. In Nitawigiwin, the young adult begins to learn about independence, procreation, parenthood, and leadership. It is also a time in which the young person learns about collectiveness to the Anishinaabe people. It is a time in which the young person might also begin to learn about medicines and ceremonies and maybe a time of initiation and convocations into a sacred lodge, which exists within Anishinaabe culture. There is a time when the young adult takes on the role of advocate and protector of the Anishinaabe system. This is where the fierceness of love and protection come into play as an Anishinaabe often does not take this role lightly. The final stage is the Kitisiwin stage in which one is an Elder. An Elder is a very important part of this process as they are the keepers of the generational window. They are the keepers of the sacred medicines, the healing lodges, the ceremonies, customs, the language, and they are the teachers. Further, the role of the Elders are to promote the knowledge and wisdom related to the people, they are the disciplinarians, they are the promoter of Anishinaabe family systems, and they guide the lives of others in their sacred responsibilities of the Creator. Jourdain (2006) discussed the cultural ceremonies associated with the Hills of Life, such as "the welcoming ceremony; naming ceremony, clan identity; walking out ceremony; fasting; initiation ceremonies; traditional practices ceremonies; and sometimes the Creator gives traditional and ceremonial leadership rights to Elders."

As in developmental tasks in European settings, cultural developmental milestones also have effects related to a lack of accomplishment. Within a cultural context, there are many variables that can constitute cultural unrest and discord. Manifestations of this unrest are included as follows:

identity crisis; lack of supportive relationships; physical, emotional, mental and spiritual disturbances; there are manifestations of dysfunctions or dependencies; and in Elders, the person may be unable to share, support, love, communicate, be confident in leadership roles, and may possibly make decisions for Anishinaabe children and families in haste

Jourdain, 2006

The possibilities that exist within the restoration of Anishinaabe systems far exceed the deficits related to restoring this type of practice with First Nations people. It is also important to note, although the research has shown only one mode of developmental milestones for Anishinaabe, specifically, Jourdain's teaching, the beauty of the Anishinaabe teachings are the diversity that exists within receiving the teachings on childhood development and rites of passage for the Anishinaabe child. When one family receives teaching on the cultural rites for a child, especially their own, there is much more meaning and attachment to the teaching received by the family, the extended family, and the community.

The second layer of the natural protective network is the family. Within the research, the definition of family is much more than the nuclear family in mainstream systems. Anishinaabe family principles are structured on value-based teaching within the concept of Naaniigan Abiinooji. The Anishinaabe family structure was a resilient mechanism in which the community all had sacred responsibility in the raising of a child and the mentoring of a fellow community member.

Jourdain (2006) has presented a collective definition of family:

Nuclear family: immediate family, mom, dad, siblings;

Extended family: Aunties and Uncles on Paternal or Maternal sides, cousins, second cousins, maternal family lineage, and paternal family lineage;

Community family: This is the membership of a First Nation community;

Nation family: These are the members which exist within a treaty. For example, Treaty #3 is a nation and those members within this area are in fact family;

Nationhood family: These are all the members of the Anishinaabe family, regardless of jurisdiction, provincial territories, or countries. It is all Anishinaabe;

Clan family: There are significant teachings on clan and clan family which details the innate relationship to each other through our spiritual clan protector;

Cultural family: The cultural family is linked to the ceremonial practices of the Anishinaabe. It is also the support within these circles of ceremonial activities.

Building on this foundation of Anishinaabe family structures, WFS has integrated a service placement model called the Cultural Placement. The principle is an ethical assumption, which is directly linked to the concepts and laws that exist in Naaniigan Abiinooji. Kishiqueb (2006) developed, presented, and discussed the implementation of this principle into practice in the early 1990s. The principle was used to offer security for the child and to ensure the continuity of placement. It is used as a mechanism to provide an opportunity for the child, family, extended family, and community to collectively raise the child within the child's cultural context. Reunifications with family systems were a prominent theme for the Anishinaabe children.

The Cultural Placement principle is as follows: If the community is aware of a child and family in need, typically the community will work with the family and attempt to provide services to mitigate the risk of harm for the child. If intervention is needed, it is based on the resources that exist with the family system. "As a first resource, the child is placed with immediate family, extended family, family within the community, extended family off reserve, family within neighbouring communities, a Native family off reserve, then a non-Native family, or other facility off reserve" (Kishiqueb, 2006). This placement principle has proven to be successful, as WFS has gone from placing children in 20% Anishinaabe homes to 85% Anishinaabe homes in 20 years of service practice. Further, in several of the communities, this principle has allowed all children to be placed within their cultural context of family and community.

Customary care

Another part of the family within this protective shield is the concept of customary care. There are many facets to customary care principles, only some of which will be discussed within this paper. Customary care principles are a way of life established by the Anishinaabe people. It is the commitment to raising the children to ensure the identity and rights of the child are adhered to, as they are a part of teaching vital life skills for each First Nations child. It is a community approach to making decisions on children and families because they know the families and the families' needs. It is built with the premise that the worker lives within the community and has more opportunity to invest in the preventative and healing interventions of child welfare practices. It is based in love for the people as the main theme of a natural helper. One interviewee stated, "Child welfare practice dictates social work education, but it is not necessary . . . I'd be irresponsible to say formalized education is not relevant but I don't think it is essential to provide culturally competent services" (WFS, 1984a). Another stated, "You need wisdom, kindness, respect . . . this far exceeds the education anybody on earth can give you because we are all human beings, let's treat each other like human beings" (WFS, 1984b). The underlying principle of customary care is the commitment to working in a respectful manner, speaking from the heart, and with the community as the voice that empowers a different approach than mainstream child welfare intervention.

The final layers of the Natural Protective Network Principle are the concepts of First Nations and nationhood governance. The people within First Nations communities need to have the power to create the services to help and heal their own people. The services need to be based on decisions made by Chiefs and Councils who consult actively with the Elders and service providers of the community. This consultation allows for the development of fundamental rights to care for children through a community perspective, which is typically based on Anishinaabe systems and structures. As many Chief and Councils monitor through portfolio systems, the supervision of such structures has typically been empowered through Family Service Committees. These committees have taken different forms and can encompass different people, but the point of consultation and supervision is the main theme noted. Grandmothers on Family Service Committees are a standard that has its roots in historical roles and structures. It is the people that make up the committees that supervise the team and direct the team in case planning and review. The team is accountable to the grandmothers of the Family Service Committees. Within this system of care, the response to services is done up front. It is an interactive response that allows for life continuity for the child. The overall system is mentored, monitored, and supported by WFS.

As an agency, WFS has developed a sound practice within the concept of Naaniigan Abiinooji – inadequately translated to the best interest of the child. This concept encompasses many of the cultural attachments necessary to the wellbeing of an Anishinaabe child. It is what we do as service providers to enhance the child's wellbeing in the areas of physical needs, emotional needs, mental needs, and spiritual needs. It is also what we do as service providers to ensure the moulding and supporting of the child's development in this area. Further, it is how we bring in family and extended family or community members in their "traditional roles" as caregivers to the child. It is the collective accountability to the child and the family. The concept of Naaniigan Abiinooji is the spiritual mechanism and/or traditional roles of helpers we need to embrace to complete this task as service providers. Stakeholders within the video footage have differentiated between the mainstream concept of the best interest of the child and Naaniigan Abiinooji, and have found key differences. Both standards agree in the basic principles of rights for the child; however, Naaniigan Abiinooji requires more. In the WFS system:

Naaniigan Abiinooji requires safety, protection, basic needs, rights to culture, Anishinaabe children's rights, traditional teachings and education, traditional developmental milestones, immediate family, extended family, all significant relationships, clan traditional or adoptive community, land, language, Anishinaabe name, treaty rights, and ischooin niin (sacred items)

Kishiqueb, 2006

As an agency, it is the responsibility of WFS to ensure access to these standards of care for children in their care, thereby allowing the community to increase community wellness and wellbeing. This is one of the inherent roles of leadership in First Nations governance and nationhood building.

The WFS model has shown the sacredness of raising an Anishinaabe child and some of the foundations based on cultural teaching of the Anishinaabe. Within the research, Elders discussed the two main teachings related to responsibility and traditional ethics inherent in leadership. Firstly, is a teaching on Oozhegwaas - a spiritual being who steals children when parents are engaged in other activities. Oozhegwas represents the possibilities of what happens when the natural protective factors that exist in First Nations communities are not working properly. It is a story about a grandmother's teaching on child care, a mother's reclaiming of her child, and a spirit being who steals a child. It is about the process the mother went through on her journey to reclaim her child and is compared to the process of various First Nations communities in their attempt to restore cultural values in Anishinaabe child welfare practice.

The second responsibility related to leadership is the concept of non-interference. The concept of non-interference has been misunderstood by non-Native people for centuries. Often times you hear a person describing the concept and the misinterpretation of the principle leaves a person wondering if it is an appropriate response. The Elders within the videos have described non-interference as understanding the sacred responsibility related to Creator's gift of free will. It is a teaching that is based in the scrutiny of life, of one's purpose, and is based in the highest of ethics and morals. It is based in a manner of thinking that is built on Naanabooz stories, creation stories, visions, and teachings of the Anishinaabe. It is a mechanism to process right and wrong, as well as to know one's place within all levels of being. Non-interference is based in the relational developmental or attachment to one's belief system – Anishinaabe – and it is the understanding of the great responsibility of choice/free will. Another way of stating it is, "the ability to choose to help or not to help, and to help all, not just Anishinaabe, but all of humanity. Ensuring we are all safe" (Henry, 2006).

Leadership in Anishinaabe is not an easy task, according to the research. There are many stages of healing and commitment that exist within the Anishinaabe system's framework. But it is important to note the question throughout the research: What foundation do we want to work from? What standards or principles do we use? And when they are defined, how can the communities work together to achieve restorative child welfare practice? This is the ethical dilemma associated with the concept of non-interference. It is a choice in leadership based on Anishinaabe cultural principles. Henry (2006) stated, "Never get complacent, Weechi-it-te-win; you are the helpers, the shakbewis, to the children, blaze a good landing spot for them, blaze a good road for them, so when they come there will be a good place for them amongst the Anishinaabe." This concept and theme is prevalent in all of the leaders of the agency and the commitment to that vision is intact.

Cultural restoration, a principle often foreign to mainstream social work practice, can seem elusive. A child welfare system can adopt strategies to improve better outcomes for First Nations children. Much of the research has shown various cultural attachment strategies to support this venture. The creation of WFS was a systematic approach to the administrative harmonization of the cultural concepts introduced in this research. The promotion of harmonization has allowed a systematic and culturally competent organization to begin to devolve services to the First Nations community through the devolutions principles. This process allows for the spiritually educated task of implementing Abiinooji Innakonegewin (Anishinaabe Child Care Law), which is the enactment of the supreme Anishinaabe law on how to care for our children. These tasks require a commitment, an anchoring in the vision, and an assertion in child welfare sovereignty for the Anishinaabe Nation.

Discussion

An implication for practice is the concept of cultural diversity that exists on Mother Earth. The fluidity of the WFS culturally restorative practice model with other Indigenous child welfare service agencies has many advantages and potential pitfalls through misapplication of the model. Cultural diversity is an essential component of this model, as it allows for the opportunity to investigate the true and Natural Laws that have been given to each Indigenous nation. The cultural investment and opportunities this project provides are endless, as each nation is rich in cultural knowledge. However, the absence of cultural leadership by the Indigenous nations into service practice could prove to be disrespectful to the central theme of culturally restorative child welfare practices, which is nationhood empowerment.

The researcher believes it is important to take the cultural attachment theory to the next level in the world of academia and social work practice. For too long, First Nations people have been subject to a mechanism that does not work and as a result, our nations have been continual victims to the shortsighted practice of policymakers, institutions, and agencies. The opportunities within cultural attachment into social work practice are an immense task. Literature, systematic study, and research analysis are needed to support this theory. The principle of increasing cultural attachment strategies into practice should increase culturally restorative nations. The Anishinaabe Nation is a proud nation of people and a theory to support that development is imperative.

Conclusion

The objective of the research was to attain and package the wisdom of WFS with a level of competence and integrity that ensures the inherent dignity and worth of this organization. It was the intent to create, share, and mentor an environment in which other populations can achieve organizational change. The research captured cultural values and the possibilities inherent in culturally restorative child welfare practices. Anishinaabe worldviews and practices have had limited admittance to literature grounded in scientific journals and the research has opened new doors and opportunities for First Nations researchers.

Cultural attachment is found in the protective network principle and culturally restorative child welfare practice is the systematic embracing of culture to meet the cultural needs of the First Nations child. Cultural attachment is one tool for the rebuilding of a nation of people. Culturally restorative child welfare practice is a conceptual framework based on the cultural teachings of a nation; it is based on the ceremonial practices; it is found in the circle of protection; it is defined by the specific roles and responsibilities of a member within a nation and their subsequent contribution to the development of the child's secure cultural attachment; it is found in the ceremonial and cultural developmental milestones with a nation; and it is the full integration of these concepts into children’s mental health and child welfare service delivery systems.