Résumés

Abstract

The Canadian healthcare system has a rich history of using public funds for medically necessary hospital and physician services, legislated by the Canada Health Act (CHA). Overlapping with this history is the fight for reproductive rights which culminated in the decriminalization of abortion in 1988. Provincial and territorial governments must ensure that residents have “reasonable access” to health services deemed “medically necessary” as per the CHA principle of accessibility; the federal government holds the authority to withhold funding to sub-national governments if violated. We demonstrate that sufficient policy and legislative evidence exists to support abortion as a medically necessary procedure in Canada. We further argue that, as a medically necessary health service, the inequitable landscape of abortion access across Canada requires vast improvements to fulfil the “accessibility” principle. Systemic and geographical barriers, a lack of culturally informed care, unwilling providers, and anti-choice influences complicate abortion access. Though accessibility has been broadened with the introduction of Mifegymiso — the gold standard for medical abortion — this has not solved the problem of access. In this paper, we argue that classifying a procedure as medically necessary, in this case abortion, requires active and sustained policy action to improve equitable access and remove barriers to care. We justify the special status we give abortion through utilitarian and justice reasons, and due to the unique barriers to care faced by patients seeking abortions.

Keywords:

- abortion,

- medical necessity,

- health policy,

- Canada Health Act,

- access to care,

- reproductive health

Résumé

Le système de santé canadien a une riche histoire d’utilisation des fonds publics pour les services hospitaliers et médicaux médicalement nécessaires, conformément à la loi canadienne sur la santé (LCS). La lutte pour les droits reproductifs, qui a abouti à la dépénalisation de l’avortement en 1988, se superpose à cette histoire. Les gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux doivent veiller à ce que les résidents aient un « accès raisonnable » aux services de santé jugés « médicalement nécessaires », conformément au principe d’accessibilité de la LCS ; le gouvernement fédéral a le pouvoir de suspendre le financement des gouvernements infranationaux en cas de violation de ce principe. Nous démontrons qu’il existe des preuves politiques et législatives suffisantes pour soutenir l’avortement en tant que procédure médicalement nécessaire au Canada. Nous soutenons également qu’en tant que service de santé médicalement nécessaire, le paysage inéquitable de l’accès à l’avortement au Canada nécessite de vastes améliorations pour satisfaire au principe d’« accessibilité ». Les barrières systémiques et géographiques, le manque de soins culturellement informés, le manque de volonté des prestataires et les influences anti-choix compliquent l’accès à l’avortement. Bien que l’accessibilité ait été élargie avec l’introduction de Mifegymiso — l’étalon-or de l’avortement médical — cela n’a pas résolu le problème de l’accès. Dans cet article, nous soutenons que la classification d’une procédure comme médicalement nécessaire, en l’occurrence l’avortement, nécessite une action politique active et soutenue afin d’améliorer l’accès équitable et de supprimer les obstacles aux soins. Nous justifions le statut spécial que nous accordons à l’avortement par des considérations utilitaires.

Mots-clés :

- avortement,

- nécessité médicale,

- politique de santé,

- loi canadienne sur la santé,

- accès aux soins,

- santé reproductive

Corps de l’article

introduction

The Canadian healthcare system has a rich history of using public funds for medically necessary procedures and treatments. Overlapping with this history is the fight for reproductive rights culminating in the decriminalization of abortion in 1988 accompanied by a long period of activism to classify abortion as a medically necessary procedure. Since then, abortion procedures have been unencumbered by additional regulations beyond those required to ensure safe, high-quality care, yet sufficient access to abortion remains a significant concern and differs greatly across the country. Those seeking abortions must navigate the many glaring barriers which delay or prevent care, including significant travel to access the closest abortion providers, a lack of willing abortion providers or institutions, and anti-choice organizations which block access to abortion services. For pregnant people past the first trimester, access to sufficient abortion care becomes even less available as procedural abortion[1] may be required, and providers are more likely to conscientiously object.

In this paper, we argue that 1) abortion is indeed a medically necessary procedure according to the Canada Health Act (CHA) and that 2) classifying abortion as a medically necessary procedure requires a greater effort toward sufficient access which is sorely lacking in the Canadian context. We start with a brief description of the Canadian healthcare system, followed by an explanation of how medical necessity is determined through the CHA, the governing policy legislature for publicly funded healthcare services. We then turn the focus to abortion, briefly explaining the history of abortion in Canada and arguing that abortion is indeed medically necessary. We show that despite abortion being classified as a medical necessity, access to this service remains a significant issue in Canada. This leads to our main argument, that improving access to abortion services is imperative based on the medical necessity criterion.

Overview of the Canadian health system

The concept of medical necessity in Canada is rooted in the formation of the publicly funded system we have today. Canada’s predominantly publicly financed and administered healthcare system is governed through 13 interlocking provincial and territorial healthcare insurance plans (2). Under the 1867 Canadian constitution, provinces and territories are assigned authority for oversight and delivery of care, giving rise to 13 healthcare systems with differing methods of payment, delivery, and outcomes for their users (3,4). As a result, access to public health services may differ from one province to another. Among other duties, the federal government is responsible for guiding the delivery of provincial healthcare under the 1984 CHA, which was designed to ensure that all eligible residents of Canadian provinces and territories have reasonable access to medically necessary hospital and physician services on a pre-paid basis (2,5).

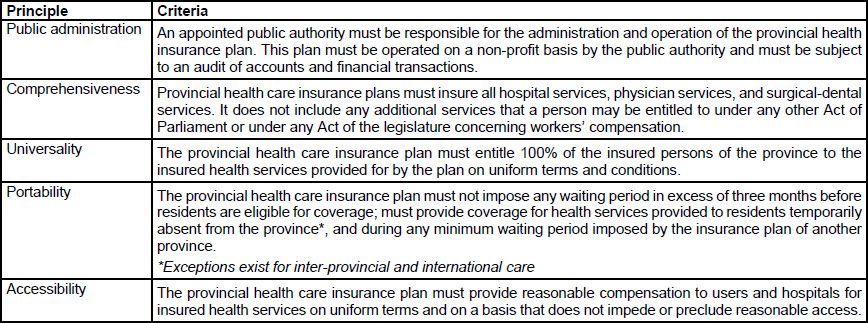

The primary objective of the CHA is to “promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of Canadian residents, facilitating reasonable access without financial or other barriers” (2). The CHA defines the national principles that govern the Canadian healthcare system: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility. To qualify for payments from the federal government for a fiscal year, the provincial health care insurance plan must satisfy these principles, whose criteria are summarized in Table 1 (2). Reimbursement for healthcare expenses is provided via the Canada Health Transfer (CHT), which aims to establish long-term predictable funding for healthcare and support under the CHA (6). If the delivery of provincial or territorial public healthcare violates the CHA, the federal government has the power to make deductions from the CHT (2,3). However, these may be reversed if corrective action is taken to re-align with the principles of the CHA — a policy that emphasizes compliance, transparency, consultation, and dialogue between levels of government (2,6). This federal-provincial/territorial cost-sharing framework for universal publicly funded care is commonly known as Medicare (3).

Table 1

Summary of the national principles required for provinces to receive funds under the Canada Health Act (CHA)

Principles have been amended from the CHA for the purposes of this paper; a more comprehensive explanation is offered in the CHA (2).

Medical necessity under the Canada Health Act

Under the CHA, “medically necessary” services are covered using public funds (5). At first glance, restricting public health insurance to cover only necessary care seems sensible. It is unlikely that the public would take kindly to funding health services that are considered unnecessary. However, the CHA does not provide a formal definition of “medically necessary”, nor is it prescriptive or suggestive as to which services should qualify (5). While some services can clearly be categorized as “medically necessary” or “medically unnecessary”, such as emergency care and elective cosmetic procedures, respectively, other procedures that exist in between these extremes can vary on “necessity”, depending on circumstance.

The conflation of “medically necessary” with “publicly insured” under the CHA means that decisions to include health services in provincial and territorial health insurance plans also designate these services as medically necessary. Whether health services are covered under public health insurance is determined through negotiations between provincial/territorial governments and their respective physician colleges or groups (5). Negotiations between sub-national governments and health providers are not open, transparent processes and do not incorporate public input. The existing process has been criticised for lending inappropriate power to physicians, creating inconsistent health services access across the country, and exacerbating inequities for vulnerable populations (7-9).

With sub-national governments holding authority over publicly insured services, the lack of a clear definition of medical necessity has led to variation in the scope and extent of coverage of health services, creating inequities in costs and accessibility (10,11). Additionally, although the CHA ensures the cost of in-hospital administered prescription drugs are publicly funded, universal coverage does not extend to other medically necessary prescriptions (12). In fact, Canada remains the only country with a publicly funded healthcare system that does not have universal coverage for drug prescriptions. While employer-based insurance plans and government plans for certain populations like older adults and Indigenous people living on reserves strive to fill this gap, 1 in 5 Canadians still pay for drugs out of pocket (13).

It has been argued that the public should play a greater role in deciding which services are covered. The decision to include or exclude a treatment in publicly funded services is inherently rooted in ethics, values, and distributive justice (7). As a last resort, individuals and groups lacking coverage for necessary health services have taken to litigation to address their grievances under s. 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (14). This constitutional provision aims to shield citizens from discrimination and has been invoked to secure rights to required health services (15,16).

Many provinces have requested more guidance in selecting medically necessary services, however, the possibility of establishing an explicit definition of “medically necessary” has been widely debated (7,17,18). For the purpose of our paper, we choose not to dive into this debate but instead to explore what it means once a health service is considered medically necessary and is therefore a publicly insured service in Canada. When provinces and territories decide to include a service under their public insurance plan, the CHA stipulates criteria and conditions that provinces and territories must meet to receive payment through the CHT (6). These criteria, discussed earlier in this paper, are summarised in Table 1.

Abortion as medically necessary

The road to incorporating abortion in the CHA, and thus recognizing it as a medically necessary service, has been a long one with notable legal, advocacy, and policy developments along the way. Interestingly, the concept of medical necessity emerges throughout this history and raises important questions as to why exactly abortion is medically necessary.

Abortion was criminalized in Canada under the original Criminal Code between 1892-1969. This restriction forced many pregnant people to seek an abortion under unsafe, unregulated conditions with high mortality rates. Between 1926-1947 alone there were an estimated 4,000-6,000 deaths attributed to unsafe abortions, though this is likely a severe underestimation (19,20). The provision of abortions in medical settings was not allowed until 1969, when “therapeutic abortion” was legalized under Section 251 of the Criminal Code, conditional upon a Therapeutic Abortion Committee (TAC) deciding if the abortion was necessary for the woman’s health (21). The TAC had to be comprised of at least three physicians — none of whom could be abortion providers. Due to the limited number of women and racialized physicians at this time, TACs were predominantly composed of white men (21).

While TACs related the concept of medical necessity to the mother’s health, this was often a narrow conceptualization of health, not taking into full account the mental, emotional, and social reasons that contribute to a decision to seek out an abortion. A 1977 survey of over 3000 Canadian physicians noted that over half considered social health to be a valid component of health to justify abortion, while over 90% cited physical health (22). Additionally, while almost 80% saw mental health as a component of health, over half thought that interpretations of mental health in the context of abortion were too liberal. Such differing moral and medical views between physicians explain why TACs were not consistent nor strictly evidence-based in determining the criteria for abortion and the laws, at this time, gave them authority to change these criteria at will. As one medical columnist wrote about the TAC, “Some patients are turned down one week but would have passed the following week.” (23 p.78)

Finally, in 1988, the Supreme Court’s decision, R. v. Morgentaler, ruled that the criminalization of abortion was unconstitutional under Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it increased health risks to women, depriving them of their right to security of the person (24). Chief Justice Dickson found that abortion under the Criminal Code law infringed on a woman’s security of the person by forcing them to continue with their pregnancy despite their priorities and aspirations, and the requirement to receive TAC approval to procure an abortion resulted in delays that increased the physical and psychological trauma involved (21,23,24). Here, we can see allusions to medical necessity being broadened to consider women’s psychological health, as well as their social health and human rights (21,24).

The landmark Morgentaler decision led to abortion being publicly funded under the CHA in the same year. This was a controversial addition as political actors and anti-choice groups have argued that abortion services fall in-between the extremes (may or may not be considered medically necessary depending on circumstance) and therefore should not be considered medically necessary under the CHA. Such arguments to defund abortion have also been made at the provincial level. In 1995, residents of Alberta petitioned the Legislative Assembly, urging the government to “de-insure the performance of induced abortion under the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan Act” (25). These efforts rely on physicians being able to parse out which abortions are medically necessary, and which are not. Here, again, medical necessity is narrowly understood as harm to the mother or fetus. However, even use of this narrow understanding of medical necessity to restrict access to some abortions has received pushback from physicians who are unable to discern criteria that would distinguish between medically necessary and medically unnecessary abortions (25).

Arguments to support fully funded and unrestricted access to abortions include those of abortion as a constitutional right and abortion as a mandatory (non-elective) procedure, since delaying and denying abortion can have life-altering consequences for the pregnant person. In Jane Doe I v. Manitoba, denial of public funding for abortion services was deemed to infringe on women’s equality rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (26). Understanding abortion as a right is largely supported by the arguments of many advocates and scholars who suggest that medical necessity should not be limited to just physical health during pregnancy and birth but must also include the social reasons that motivate abortion and are themselves inextricably tied to health (27). Indeed, if health is considered to include physical, emotional, and social wellbeing (28), then the concept of medical necessity will be sensitive to the social harms of unwanted pregnancies to a person’s financial, economic, and social wellbeing. Forms of social oppression, including lack of housing, precarious work, and poor education, are related to poor health; pregnant people seeking abortions to avoid or ameliorate these conditions can be said to be accessing a medically necessary service to improve or preserve health.

Despite continued anti-choice rhetoric, policy and legislative evidence since its decriminalization has positioned abortion firmly within the CHA as a medically necessary service. Therefore, while abortion is deemed to be medically necessary for a myriad of physical, psychological, and social health reasons, it is definitively medically necessary in Canada through the authority of the CHA. Professional governing bodies for physicians, such as the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, also stand firmly behind the inclusion of abortion in the CHA as an essential service (29). Perhaps most importantly, the federal government has used the inclusion of abortion as a medically necessary service to penalize provinces that are not appropriately funding abortion services. The 2022-2023 Canada Health Act Annual Report noted deductions made from New Brunswick and Ontario due to CHA compliance issues related to abortion care (29). For example, New Brunswick only offers public insurance for abortions provided in hospitals, which infringes on the Public Administration criterion under the CHA. As a result, $64,850 was deducted from New Brunswick’s CHT payments in March 2021, 2022, and 2023. The amount represents an estimate of patient charges based on evidence provided by Clinic 554 and Canadian Institute for Health Information data (30,31).

Barriers to abortion access in Canada

Thus far, we have described the role of medical necessity in the governing policy for publicly funded health care services in Canada, the CHA. Further, we have shown that abortion is medically necessary according to Canadian health policy, law, and advocacy. Before taking this one step further to argue that classifying abortion as medically necessary requires going beyond funding to address issues of access, we must first establish accessibility to abortion as a fundamental issue in Canada, and one where lack of access would violate the fifth principle of the CHA.

Although abortion services are available in all provinces and territories, the 2016 UN Human Rights Commissioner’s report noted a lack of access to abortion in Canada, calling on the government to address the main access issues of cost, geography, and knowledge (32). A pregnant person’s access can be complicated by where they live; this is especially true for the 17.8% of Canadians who live in rural and remote communities (33). Historically, free-standing abortion clinics and hospital-based abortion services have been concentrated in urban centres, limiting rural and remote individuals’ access to timely care while burdening patients with additional travel-related costs (34-36).

Conscientious objections from unwilling healthcare providers also create unpredictable gaps in abortion access. While physician codes of ethics and professionalism vary provincially, according to the CMA, “a physician should not be compelled to participate in the termination of a pregnancy,” and “a physician whose moral or religious beliefs prevent him or her from recommending or performing an abortion should inform the patient of this so that she may consult another physician” (37). This directly conflicts with a patient’s right to access medically necessary care. Objecting physicians often gatekeep care by failing to provide effective referrals for abortion services. Effective referrals must connect patients to a willing, available provider in a timely manner (38). Despite the importance of appropriate and timely referrals, written provisions from physician colleges expressing conscientious objectors’ duty for effective referrals exists only in Ontario and Nova Scotia, and regulatory bodies often fail to penalize providers who do not comply (39,40).

Since individual healthcare practitioners can conscientiously object on a case-by-case basis, the total number of willing providers in Canada is constantly in flux. Creating a database of willing providers is a controversial solution as 1) willing providers can burn out over time after providing the emotional care necessary for abortion, and 2) some willing providers wish not to be publicly identifiable for fear of targeted attacks from anti-choice groups (41,42). Finding solutions for such issues has been difficult since wide-ranging policies and guidelines tend to either reduce access to care for patients or compel healthcare practitioners to act in conflict with their moral or religious beliefs. Institutional conscientious objection exacerbates this issue — where publicly-funded Catholic institutions are permitted to deny abortion services through their right to religious freedom under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. While staff may advocate for access to abortion and contraceptive services, these can be denied due to the religious values of the institution imposed by the power of the Catholic church (43,44).

Access to evidence-based information can also serve as a barrier to individuals accessing abortion. In the quest for abortion information and care, patients may unknowingly fall victim to a crisis pregnancy centre (CPC), organizations which claim to provide a range of free services for pregnant people to better understand their options (45). In reality, they are anti-choice agencies that deceive pregnant people and spread misleading or inaccurate information about abortion, contraception, and reproductive health (46). They are often driven by ulterior motives — 96% of CPCs have religious affiliations or agendas, despite only 24% making this publicly known. CPCs have steadily grown in number since the decriminalization of abortion, with 150 anti-choice CPCs identified across Canada as of 2024 (47). The Federal Liberal government committed to no longer providing charity status to anti-abortion organizations such as CPCs as part of their 2021 election platform but has yet to follow through on this promise (48).

A positive start

While misinformation, conscientious objection by providers, and geographical gaps in care still create barriers to accessing medically necessary care, Canada has taken positive steps to improve access. In 2017, Mifegymiso, the gold standard for medication abortion (MA), became available in Canada. When first introduced, restrictive regulations around prescribing and dispensing Mifegymiso limited public access to the medication (49). These regulations included mandatory training modules for prescribing health professionals and an ultrasound to rule out ectopic pregnancy and assess the gestational stage (50,51). However, within a year of Mifegymiso being available on the market, many restrictive regulations began to be removed by Health Canada, with all being removed by 2019 (51,52).

Mifegymiso represents a positive start toward increasing abortion access across the country, particularly for pregnant people in rural areas. Norman et al. reported that the increased availability of MA in 2019 was associated with a twelve-fold increase in the provision of abortions across Ontario’s rural communities (53). This expanded access was also supported by the allowance of health practitioners besides physicians to prescribe and dispense MA, including nurse practitioners and pharmacists (54,55).

Despite these examples of increased access, studies surveying health professionals have maintained that anti-choice stances and conscientious objection in health organizations actively prevented health practitioners from providing MAs (50,54). Some examples described in a survey study by Munro et al. were “hospital staff who refused to clean clinic rooms where abortion care was provided, hospital administrators who ignored requests to implement an MA protocol, and community pharmacists who refused to dispense mifepristone” (50). In the same study, health practitioners commented on concerns about the loss to follow-up for post-abortion care among rural patients commuting significant distances to access their MA prescription (50). These points support that while Mifegymiso does represent a step forward in abortion access, issues of access that preceded this new availability of MA still permeate the Canadian health system.

It is also important to acknowledge that Mifegymiso can be prescribed only until nine weeks for on-label use, meaning the medication has a limited impact on abortion access after 10 weeks (49). A study looking at the off-label use (after 10 weeks) of Mifepristone for second- and third-trimester MAs found that access was concentrated in urban areas (56). Specialists who manage MA and procedural abortion cases after the first trimester tend to be concentrated in urban centres (56). Some practitioners also express that it may be more “feasible and private” for rural patients to access a procedural abortion as it reduces the need for post-abortion follow-ups (50). These challenges disproportionately affect Indigenous patients, as over half of people living in Indigenous communities live in the most remote parts of Canada (36). Canada’s pervasive systems of colonialism and racism leave Indigenous communities to face intersecting barriers to care and a lack of access to health services generally (36). Access isn’t enough — Canada’s dark history of controlling Indigenous People’s reproductive rights through forced sterilization and abortion, child apprehension, and violence from healthcare providers highlights the need for culturally-safe abortion care for this population (57).

Abortion as medically necessary: Making the case for better access

In the preceding sections, we have shown that medical necessity is a guiding principle in granting public funding for abortion and other publicly funded services in Canada. Importantly, we submit that while abortion is likely medically necessary for a multitude of physical, psychological, and social health reasons, it definitively is medically necessary according to the CHA. We now take this argument one step further to argue that deeming abortion as medically necessary requires moving towards sufficient access to abortion services. Although improved access to care followed the introduction of Mifegymiso in 2017, barriers to access still exist for abortion services. We argue that classifying abortion as a medical necessity necessitates better access to abortion services through 1) the internal logic of the CHA, 2) the rationale of universal health coverage, and 3) an intuitive understanding of medical necessity. We address each of these arguments in turn.

Justifying abortion access through the internal logic of the CHA

Despite inconsistencies in the determination of medical necessity in Canadian health policy, we have demonstrated that abortion is classified as a medically necessary service according to the CHA. This means that it is subject to the five CHA principles: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility. In this context, accessibility means that insured persons in Canada must have “reasonable access to insured hospital, medical and surgical-dental services on uniform terms and conditions, unprecluded or unimpeded, either directly or indirectly, by charges (user charges or extra-billing) or other means (e.g., discrimination on the basis of age, health status or financial circumstances)” (30). Any medical procedure or service that is deemed medically necessary under the CHA is subject to the principle of accessibility. However, not all Canadians have reasonable access to abortion.

New Brunswick has been penalized multiple times for imposing user charges for accessing abortion, charging up to $850 for abortion depending on the gestational term (30,58). Approximately $334,766 from the federal health transfer was withheld from New Brunswick but the province continues to deny that their actions violate the CHA making resolution unlikely and suggesting that user charges in the province will continue (59). Additionally, financial circumstances continue to be a significant barrier to accessing abortion in Canada. While abortion is covered by public funds, the lack of access creates barriers that require financial solutions. A person who is pregnant in the Northwest Territories may require a substantial amount of travel funds to access sufficient abortion care in a regional centre. A positive step towards removing these barriers has been demonstrated by the Northern Options for Women (NOW) program, which covers travel costs for NWT residents who must travel to Yellowknife or Inuvik to access Mifegymiso treatment (60).

Justifying abortion access through commitments to universal health coverage

Improving access to services is also essential under the rationales for universal health coverage that Canada aims to uphold. Canada has a strong history of protecting public coverage for medically necessary physician and hospital services and preventing private insurance from entering the public market (61). For example, a decade-long court case initiated by Cambie Surgeries Corporation that sought to implement a system of private insurance and user charges for Medicare-insured services in British Columbia (BC) was unanimously struck down by the BC Court of Appeal in “ongoing defence of universally accessible health care” (62). While the CHA was not directly implicated in the case, the federal government was highly supportive of the BC government’s decision which prioritized equity, fairness, and medical need over profit and ability to pay.

Overall, this seems to suggest that Canada takes great pride in the model of publicly funded universal health coverage, and this has been verified through opinion polls examining public perspectives of Medicare (63,64). However, it is important to consider what a strong commitment to universal health coverage means for ensuring adequate access to abortion. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), universal health coverage “means that all people have access to the health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship. It includes the full range of essential health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care” (65).

Canada’s form of universal health coverage can be considered “narrow but deep” — only medically necessary physician and hospital services are covered by insurance, but they are covered completely (or at least should be) (2). However, cracks in the system make the leap from coverage to access perilous. “Universal health coverage is attained when people actually obtain the health services they need and benefit from financial risk protection” — in short, a commitment to universal coverage loses meaning when people are not able to access the services to which they supposedly have a right (66). The inability to access abortion due to geography, gestational limits, and a lack of available and willing providers means that patients often do not have the opportunity to exercise the promise of universal health coverage. Making strong commitments toward access to abortion services can ensure that Canada’s commitment to universal health coverage recognizes the important ties between coverage and access to medically necessary services.

Justifying abortion access through an intuitive understanding of medical necessity

While the CHA’s accessibility criterion stipulates that medically necessary services should be provided with “reasonable access”, the lack of equity considerations surrounding what constitutes reasonable access has been challenged. Scholars have criticised the lack of attention to barriers, beyond cost, that limit access to health services as acting to perpetuate health inequities (67). Without attention to these barriers, the federal government’s criterion for access is sufficiently met by providing public funding for these services, but this is a critical limitation of what medical necessity should entail. Moving toward better access for medically necessary services like abortion makes intuitive sense. Anyone who seeks healthcare within a publicly funded system presumably assumes that, besides not having to pay for the service, they will be able to obtain the care they need. The extensive body of research examining barriers to accessing abortion in Canada all conclude that these barriers are unacceptable, especially under a system of public funding (68,69). Despite medical necessity not being legislatively defined under the CHA, it still has a social and cultural meaning for Canadians.

Utilitarian and justice reasons to prioritize abortion access

Thus far, we have argued that the language of medical necessity in the CHA, the commitment to universal health coverage which underlies Canada’s healthcare system, and an intuitive understanding of medical necessity all point to policy action for better access to abortion services. Of course, there are many other services that are classified as medically necessary under the CHA. Opponents may argue that all services should therefore be afforded better access. While we agree that all medically necessary medical and physician services should be accessible to Canadians, we argue that abortion should be prioritized due to utilitarian and justice reasons and because of unique barriers to access specific to abortion.

Abortion is one of the most common medical services accessed in Canada. It has been estimated that 1 in 3 Canadian women will have an abortion at some point in their lifetime (53). A Canadian study of over 1000 women from 17 free-standing abortion clinics found that, prior to Mifegymiso being made available in Canada, 18% of women had travelled over 100km to access abortion care (34). While Mifegymiso has certainly changed the landscape and made access to abortion easier for many, intersecting geographic, financial, and knowledge barriers persist. Considering the sheer number of people in Canada who will need to access an abortion at some point in their lives and how many of those will be affected by barriers to accessing care, responding to inequitable access to abortion is essential.

Social and reproductive justice concerns also motivate the special status we give to abortion. The previously cited study about geographic and spatial disparities in accessing abortion found that Indigenous women were three times more likely to have travelled over 100km to obtain an abortion than white women (34). People who are younger, lower-income, racialized, those who do not speak English or French, and those with immigrant or refugee status are significantly more likely to experience barriers to accessing abortion due to structural inequities (53,69). Improving access to abortion, especially for persons who are already vulnerable and over-exposed to barriers to access, is a social justice issue.

Reproductive justice highlights the importance of self-determination and bodily integrity for individuals with female reproductive anatomy and stems from a longstanding history where those who could become pregnant were denied autonomy over childbearing decisions (e.g., abortion, contraception) (70). Historically, controlling reproductive rights has been a tool for the gender-based oppression in society. Recent legal movements in the US which restrict or outright ban access to abortion highlight the precarity of reproductive rights, especially in anti-progressive political landscapes (71,72). While abortion has been decriminalized in Canada since 1988, provincial regulations that seek to limit access to care invoke strong reproductive justice concerns. For example, until recently, regulation 84-20 in New Brunswick limited access to procedural abortion in the province to only three hospitals, leaving 90% of residents without access to procedural abortion services in their local community (73). Recognizing this gap in access, New Brunswick was the first province to offer Mifegysmiso free of charge, radically improving early access to care up to 10 weeks of gestation (74). However, individuals past the gestational limit for MA may have struggled with the time, travel, and/or resource expenditure of accessing an abortion within or outside the province, restricting their ability to exercise their fundamental reproductive choice.

Finally, abortion is subject to barriers to access that are not seen with other procedures. We highlight three critical concerns: conscientiously objecting providers, conscientiously objecting institutions, and CPCs. The extent of these barriers to abortion has been previously discussed, so we only briefly reiterate them here. Conscientious objection allows providers to refuse to provide abortions on religious or moral grounds; while this advances the rights of providers, it can interfere with a patient’s ability to access care (40). This is exacerbated in rural areas where the only healthcare provider in the area might be a conscientious objector. Even when required to provide effective referrals for abortion, objecting providers can block access by refusing or delaying such referrals.

In Canada, entire institutions, often hospitals with religious affiliations, can refuse to provide abortion care on their premises (43,44). Again, this becomes a significant issue in rural areas where the sole hospital may not provide procedural abortion services, requiring patients to travel great distances to obtain needed care. Since the introduction of Mifegymiso in 2017, the proportion of MAs has increased, reducing the impact of this barrier (75). However, access to MA is still complicated by rurality, as finding a willing primary care provider and pharmacist may be challenging depending on location. Additionally, access to procedural abortion remains a complicated issue for individuals past the gestational limits to access MA. Finally, CPCs continue to unjustly interfere with access to abortion by deceptively posing as abortion clinics that provide medical services, while in fact promoting anti-choice ideals (45,46). Pregnant people who unknowingly visit these clinics are often shamed and fear-mongered into keeping their pregnancy based on false information.

While other procedures may also evoke social justice or reproductive justice concerns or face unique barriers to access, few if any procedures raise all these issues simultaneously. Therefore, we argue that access to abortion must be given special status among the larger family of medically necessary services as classified by the CHA.

Operationalizing medical necessity as access to abortion

We have argued that classifying abortion as a medically necessary procedure in Canada means taking serious efforts towards ensuring equitable access to abortion services. This induces a responsibility; however, it is worth asking upon who this responsibility falls. While we open the conversation at this time to other advocates and researchers, we offer here our thoughts on the issue. We realize that we have drawn on the use of medical necessity at the policy level; that is, within the CHA. Therefore, we shift the responsibility of access back to the provincial governments, which are bound by the CHA and the federal government, which is positioned to enforce it; together the provincial-territorial and federal governments must make the necessary policy decisions to improve access to abortion services.

There have been numerous suggestions to improve access to abortion in Canada. The introduction of medical abortion through Mifegymiso is one such essential policy which has had a significant positive impact on access since its implementation (55). Other suggestions include improved abortion-focused medical education, expanding scope of which medical professions can provide abortions, and ceasing government support of anti-abortion groups and crisis pregnancy centres (76-79). One particularly contentious suggestion is to disallow provider and institutional conscientious objection, requiring all trained healthcare providers and eligible institutions to provide abortions. We believe that our conception of medical necessity as access can be used to justify disavowal of conscientious objection where such objection significantly impedes access.

In Canada, while healthcare professionals may object to providing abortion care on moral or religious grounds, they still have a duty not to abandon their patients (80,81). This may apply to the provision of abortion care by primary care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners) and/or the dispensing of medication by pharmacists (38). Various professional colleges have guidelines to reconcile patient and provider rights, and while these duties vary between provinces/territories, they generally require providers to uphold respect for patient dignity and autonomy, and refrain from impeding access to care (38-40,81-83). Some provinces have policies requiring physicians to provide effective referrals to someone who will provide the service (ON, NS), or someone who can provide more information to the patient (NB, PEI, QC, SK, AB) (39). Under the Canadian Nurses’ Code of Ethics, NPs must provide quality care until alternative care arrangements are made in order to meet the patient’s needs (82).

Compounding the duty of healthcare providers to not abandon their patients with the duty of policymakers to ensure access to abortion as a medically necessary service, conscientious objection may not be appropriate, especially in rural and remote regions that have fewer providers. At the very least, decision makers may be obligated to strictly enforce effective referral policies, oversee whether such referrals are occurring without undue burden on the patient, and appropriately sanction practitioners who fail to refer or impede timely access to care. Currently, no such mechanism is in place to hold providers accountable for their obligations (40). While patients can file a complaint with a provider’s professional college, this may be difficult for patients who do not want to challenge an authority figure for a highly stigmatized medical procedure like abortion.

Institutional conscientious objection is even more vulnerable to our conceptualization of medical necessity as access as there is no affirmed legal right for hospitals to deny care on religious grounds (84). Further, faith-based hospitals are part of the publicly funded healthcare system and are therefore significantly financed through tax dollars in Canada. However, these institutions routinely refuse to provide abortion and become institutions of poor access, especially in regions where the sole hospital in the area is faith-based (44,45). While hospitals could receive legal challenge from patients, this is unlikely due to cost and time burdens associated with such complaint. Unsurprisingly then, most abortions in Canada are provided in clinics rather than hospitals (85). Again, it is the responsibility of provincial governments to challenge the legitimacy of conscience claims by faith-based institutions as they are obligated to provide medically necessary hospital-based and physician services.

Overall, our operationalization of medically necessary as access is policy oriented. Of course, this will intersect with the duties of healthcare providers who must abide by government and regulatory policies. However, equitable access to abortion is fundamentally a policy issue which must be addressed through sustained action by decisionmakers in government and other authoritative institutions (like medical colleges) who have the power to make change.

Conclusion

While the decriminalization of abortion in 1988 continues to be a Canadian milestone in advancing access to safe abortions, the continued inaccessibility that has persisted in the ensuing decades is a cause for concern. Abortion is considered a medical necessity according to the CHA, yet sophisticated, interdisciplinary solutions are greatly needed to prove to Canadians that the status of “medically necessary” granted to abortion is not hollow. This requires decisive action by policymakers and governments to prioritize equitable access to abortion services across Canada, with special attention given to the inequities faced by Indigenous people and those living in rural areas. We commend the recent positive steps Canada has taken by expanding access to Mifegymiso (52). COVID-19 was also a catalyst for change as Health Canada laid the groundwork for a rapid transition to telemedicine allowing people to access medical abortions through virtual consultations (49,51). These necessary steps must fit within a larger, sustained movement to promote equitable access to abortion services. This paper provides a framework to prioritize policy action on access to abortion services in Canada by situating the imperative for access within the notion of medical necessity.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements / Remerciements

RD holds a doctoral Canada Graduate Scholarship through the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). KB is a recipient of the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship from SSHRC.

RD est titulaire d’une bourse d’études doctorales du Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada (CRSH). KB est récipiendaire de la bourse d’études supérieures du Canada Vanier du CRSH.

Notes

-

[*]

RD and KB share first authorship for the paper; other authors are listed in order of contributions.

-

[*]

RD and KB share first authorship for the paper; other authors are listed in order of contributions.

-

[1]

We use procedural abortion in place of surgical abortion, as the abortion procedure is not a surgery. Procedural abortion is therefore more clinically accurate (1).

Bibliography

- 1. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. ACOG Guide to Language and Abortion. Washington, DC.

- 2. Canada Health Act, RSC 1985, c. C-6, ss. 18-20.

- 3. David Naylor C, Boozary A, Adams O. Canadian federal-provincial/territorial funding of universal health care: Fraught history, uncertain future. CMAJ. 2020;192(45):E1408-12.

- 4. Romanow RJ. Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada. Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002.

- 5. Health Canada. Canada’s Health Care System. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 1999.

- 6. Department of Finance Canada. Canada Health Transfer. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2022.

- 7. Romanow RJ. Medically Necessary: What Is It, and Who Decides? Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002.

- 8. Collier R. Medically necessary: Who should decide? CMAJ. 2012;184(16):1770-71.

- 9. Griener G. Defining medical necessity: challenges and implications. Health Law Review. 2001;10:6.

- 10. Torgerson R, Wortsman A, McIntosh T. Towards a Broader Framework for Understanding Accessibility in Canadian Health Care. Canadian Nurses Association; May 2006.

- 11. Chowdhury MZI, Chowdhury MA. Canadian health care system: who should pay for all medically beneficial treatments? A burning issue. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation. 2018;48(2):289-301.

- 12. Wilton D, Darcy M, Li C, Ziegler B. Pharmacare Now!: A Prescription for Equity. Ontario Medical Students Association. 28 May 2022.

- 13. Canada needs universal pharmacare. The Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1388.

- 14. Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

- 15. Auton (Guardian ad litem of) v. British Columbia (Attorney General). 2004 SCC 78.

- 16. Cameron v. Nova Scotia (Attorney General). 1999 CanLII 13555 (NS SC).

- 17. Caulfield TA. Wishful thinking: defining “medically necessary” in Canada. Health Law Journal. 1996;4:63-85.

- 18. Charles C, Lomas J, Giacomini Bhatia M, Vincent VA. Medical necessity in Canadian health policy: four meanings and . . . a funeral? The Milbank Quarterly. 1997;75(3):365-94.

- 19. Kieran S. 1960s to 1980s. The Morgentaler Decision.

- 20. Kotlier DB. Accessibility of abortion in Canada: Geography as a barrier to access in Ontario and Quebec. Inquiries Journal. 2016;8(6).

- 21. Dunsmuir M. Abortion: Constitutional and Legal Developments. Ottawa: Law and Government Division. 89-10E. 1989/1998.

- 22. Ministry of Supplies and Services. Report of the Committee on the Operation of the Abortion Law. Bora Laskin Law Library. Ottawa; 1977.

- 23. McDaniel SA. Implementation of abortion policy in Canada as a women’s issue. Atlantis. 1985;10(2):74-91.

- 24. R. v. Morgentaler. [1988] 1 SCR 30.

- 25. Hansard. Legislative Assembly of Alberta. Edmonton, Alberta. 11 Oct 1995.

- 26. Erdman JN. In the back alleys of health care: abortion, equality, and community in Canada. Emory Law Journal. 2007;56(4):1093-1155.

- 27. Kaposy C. The public funding of abortion in Canada: going beyond the concept of medical necessity. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy. 2009;12(3):301-11.

- 28. World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 1946.

- 29. SOGC. Access to Medical Abortion in Canada: A Complex Problem to Solve. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada.

- 30. Health Canada. Canada Health Act Annual Report 2022-2023. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2024.

- 31. Shaw D, Norman WV. When there are no abortion laws: A case study of Canada. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2020;62:49-62.

- 32. United Nations. Concluding observations on the combined 8th and 9th periodic reports of Canada : Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. New York: United Nations; 2016.

- 33. Charbonneau P, Martel L, Chastko K. Population growth in Canada’s rural areas, 2016 to 2021. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 9 Feb 2022.

- 34. Sethna C, Doull M. Spatial disparities and travel to freestanding abortion clinics in Canada. Womens Studies International Forum. 2013;38:52-62.

- 35. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. Access to abortion in rural/remote areas. Position paper #7. July 2020.

- 36. Smart K, Osler G, Young D. Commentary: Abortion is health care. Full stop. Canadian Medical Association. 8 Jul 2022.

- 37. Blackmer J. Clarification of the CMA’s position concerning induced abortion. CMAJ. 2007;176(9):1310.

- 38. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Human Rights in the Provision of Health Services. 2008/2023.

- 39. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. The refusal to provide health care in Canada: a look at “belief-based care denial” policies in Canadian health care. Position paper No. 95. Vancouver (BC); Nov 2022.

- 40. Dickens BM. Conscientious objection and the duty to refer. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2021;155(3):556-60.

- 41. Hanna DR. The lived experience of moral distress: nurses who assisted with elective abortions. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2005;19(1):95-124.

- 42. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. Anti-choice violence and harassment. Position paper #73. Apr 2018.

- 43. Glauser W. Faith and access: the conflict inside Catholic hospitals. The Walrus. 23 Feb 2022.

- 44. Flynn C, Wilson RF. Institutional conscience and access to services: can we have both? AMA Journal of Ethics. 2013;15(3):226-35.

- 45. Li H. Crisis pregnancy centers in Canada and reproductive justice organizations’ responses. Global Journal of Health Science. 2019;11(2):28-41.

- 46. Arthur J, Bailin R, Dawson K, et al. Review of “crisis pregnancy centre” websites in Canada. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. May 2016.

- 47. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. List of anti-choice groups in Canada. 13 Mar 2025.

- 48. Liberal Party of Canada. Protecting your sexual and reproductive health and rights. 2021.

- 49. Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights. Access at a glance: abortion services in Canada. 7 Jul 2022.

- 50. Munro S, Guilbert E, Wagner MS, et al. Perspectives among Canadian physicians on factors influencing implementation of mifepristone medical abortion: a national qualitative study. Annals of Family Medicine. 2020;18(5):413-21.

- 51. Health Canada. Health Canada updates prescribing and dispensing information for Mifegymiso—Recalls, advisories and safety alerts. Government of Canada; 2021.

- 52. Government of Canada. Regulatory decision summary for mifegymiso. Drug and Health Product Portal. 2025.

- 53. Norman WV. Induced abortion in Canada 1974-2005: trends over the first generation with legal access. Contraception. 2012;85(2):185-91.

- 54. Carson A, Cameron ES, Paynter M, et al. Nurse practitioners on ‘the leading edge’ of medication abortion care: A feminist qualitative approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2023;79(2):686-97.

- 55. Zusman EZ, Munro S, Norman WV, Soon JA. Pharmacist direct dispensing of mifepristone for medication abortion in Canada: a survey of community pharmacists. BMJ Open. 2022;12(10):e063370.

- 56. Renner RM, Ennis M, Contandriopoulos D, et al. Abortion services and providers in Canada in 2019: results of a national survey. CMAJ. 2022;10(3):E856-64.

- 57. Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights. Abortion Access and Indigenous Peoples in Canada. 2021.

- 58. Clinic 554. Reproductive health.

- 59. Ibrahim H. Feds penalize province for lack of abortion access, but reimburse payments because of COVID-19. CBC News. 9 Apr 2020.

- 60. Health and Social Services. Mifegymiso in the Northwest Territories. Government of the Northwest Territories.

- 61. Frank J, Pagliari C, Donaldson C, Pickett KE, Palmer KS. Why Canada is in court to protect healthcare for all: Global implications for universal health coverage. Frontiers in Health Services. 2021;1:744105.

- 62. Health Canada. Statement from the Minister of Health on the British Columbia Court of Appeal’s decision in the Cambie Surgeries case. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 15 Jul 2022.

- 63. Abelson J, Mendelsohn M, Lavis JN, Morgan SG, Forest PG, Swinton M. Canadians confront health care reform. Health Affairs. 2004;23(3):186-93.

- 64. Neustaeter B. More than half of Canadians uncomfortable with private health care options: Nanos. CTV News. 6 Sept 2021.

- 65. World Health Organization. Universal health coverage. 2025.

- 66. Evans DB, Hsu J, Boerma T. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(8):546-46A.

- 67. Birch S, Abelson J. Is reasonable access what we want? Implications of, and challenges to, current Canadian policy on equity in health care. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation. 1993;23(4):629-53.

- 68. Keer K, Benjamin K, Dhamanaskar R. Abortion in Canada is legal for all, but inaccessible for too many. Policy Options. 18 Aug 2022.

- 69. Kaposy C. Improving abortion access in Canada. Health Care Analysis. 2010;18(1):17-34.

- 70. Hyatt EG, McCoyd JL, Diaz MF. From abortion rights to reproductive justice: a call to action. Affilia. 2022;37(2):194-203.

- 71. Totenberg N, McCammon S. Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, ending right to abortion upheld for decades. NPR. 24 Jun 2022.

- 72. Abortion Finder. State-by-State Guide. 2025.

- 73. General Regulation - Medical Services Payment Act, N.B. Reg. 84-20 and CCLA v. PNB, 2021 NBQB 119.

- 74. CBC. New abortion care network seeks to improve access in N.B. CBC News. 27 Jan 2023.

- 75. Schummers L, Darling EK, Dunn S, et al. Abortion safety and use with normally prescribed mifepristone in Canada. NEJM. 2022;386(1):57-67.

- 76. Myran DT, Bardsley J, El Hindi T, Whitehead K. Abortion education in Canadian family medicine residency programs. BMC Medical Education. 2018;18:121.

- 77. Dunn S, Brooks M. Mifepristone. CMAJ. 2018;190(22):E688.

- 78. Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights. Increasing abortion access in Canada through Midwife-led care. 2023.

- 79. Weeks C. Liberals urged to fulfil promise to cease funding to anti-abortion groups, crisis pregnancy centres. The Globe and Mail. 11 Jul 2022.

- 80. Canadian Medical Protective Association. Who we are.

- 81. Canadian Medical Association. Code of Ethics and Professionalism. 2018.

- 82. Canadian Nurses Association. Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses. 2017.

- 83. Ontario College of Pharmacists. Code of Ethics. Nov 2022.

- 84. Sachdeva R. Abortion accessibility in Canada: The Catholic hospital conflict. CTV News. 19 May 2022.

- 85. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. Statistics – Abortion in Canada. Vancouver (BC): June 2025.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Summary of the national principles required for provinces to receive funds under the Canada Health Act (CHA)