Abstracts

Abstract

While professional interpreters are trained to interpret in direct speech style, using the “direct interpreting approach” (Hale 2007), studies show that some interpreters deviate from this style, with implications for their role performance. Few of these studies, however, have examined the interpreters’ style choice in relation to their professional qualifications and ethics. Drawing on data from an ethnographic investigation of interpreted lawyer-client interviews in Australia, this study explores interpreters’ choice of interpreting style in line with their professional qualifications, the reasons behind their choice and the implications for their role performance. It found that trained interpreters used direct speech consistently and understood the rationale behind this ethical requirement. Untrained interpreters either ignored this norm or had difficulty adhering to direct speech style and its associated interpreting approach in a consistent manner. They shifted to reported speech on various occasions to achieve different communication purposes, some of which indicate their assumption of roles not stipulated in their professional ethics. The untrained interpreters’ lack of compliance with the normative practice relates to their inadequate understanding of some aspects of the interpreter’s ethical role.

Keywords:

- direct interpreting approach,

- reported speech,

- interpreter’s role,

- ethics,

- lawyer-client interviews

Résumé

Bien que les interprètes professionnels soient formés pour interpréter dans le style du discours direct en utilisant l’« approche de l’interprétation directe » (Hale 2007), des études montrent que certains interprètes s’écartent de ce style, ce qui n’est pas sans répercussion sur leur performance. Cependant, peu de chercheurs se sont penchés sur les liens entre le style d’interprétation choisi et les qualifications des interprètes, ainsi que leur positionnement éthique. S’appuyant sur les données d’une enquête ethnographique sur les entretiens interprétés entre avocats et clients en Australie, la présente étude examine les styles d’interprétation choisis par les interprètes en fonction de leurs qualifications professionnelles, en soulignant les raisons de leur choix et les implications pour leur performance. L’étude révèle que les interprètes formés utilisent systématiquement le discours direct et comprennent la raison de cette exigence éthique. Les interprètes non formés, soit ignorent cette norme, soit démontrent des difficultés à s’en tenir au style du discours direct et à l’approche d’interprétation qui y est associée. Ils passent au discours rapporté à diverses occasions pour atteindre différents objectifs de communication, parfois en prenant des rôles qui dépassent leur code d’éthique professionnelle. Le non-respect de la pratique normative chez les interprètes non formés semble lié à une compréhension inadéquate de certains aspects du rôle éthique de l’interprète.

Mots-clés :

- approche d’interprétation directe,

- discours rapporté,

- rôle de l’interprète,

- éthique,

- entretiens avocat-client

Resumen

Aunque a los intérpretes profesionales se les forma para que interpreten con un estilo de discurso directo según el “enfoque de interpretación directa” (Hale 2007), los estudios muestran que algunos intérpretes se desvían de este estilo, con implicaciones para su desempeño. Sin embargo, pocos de estos estudios han examinado los vínculos entre el estilo de interpretación elegido y las cualificaciones profesionales y la postura ética de los intérpretes. A partir de los datos recogidos gracias a una investigación etnográfica sobre entrevistas interpretadas entre abogados y clientes en Australia, este estudio explora los estilos de interpretación elegidos en relación con la cualificación profesional de los intérpretes, y destaca las razones que motivan su elección y las implicaciones para el desempeño de su función. El estudio revela que los intérpretes con formación utilizan sistemáticamente el discurso directo y comprenden la razón de ser de este requisito ético. Los intérpretes sin formación desconocen esta norma o tienen dificultades para adherirse al estilo de discurso directo y al enfoque de interpretación asociado. Pasan a utilizar el discurso indirecto en varias ocasiones para alcanzar diferentes objetivos de comunicación, asumiendo a veces funciones no estipuladas en su código ético profesional. El hecho de que los intérpretes sin formación no se adhieran a la práctica normativa parece estar relacionado con una comprensión inadecuada de algunos aspectos de la función ética del intérprete.

Palabras clave:

- enfoque de interpretación directa,

- discurso indirecto,

- función del intérprete,

- ética,

- entrevistas entre abogado y cliente

Article body

1. Introduction

Interpreters interpreting in direct speech, that is, using the same first or second grammatical persons as the speakers, is considered an important and readily noticeable sign of professionalism (Bot 2005). It has been argued that this interpreting style helps to retain the speaker’s perspective (Bot 2005: 237), helps the interpreters achieve accuracy (Hale 2004) as well as remain neutral (Cheung 2014; Wadensjö 1998/2014), thus creating the illusion of a direct exchange between parties who do not share the same language (Wadensjö 1997). Direct speech stands in contrast to interpreters’ use of reported speech in the third person to refer to the source language speakers. In using the third person, interpreters fail to “repeat,” but rather “report what the primary speakers said in a different language,” which is not what “they are expected to do” (Bot 2005: 258; original italics). The interpreter’s professional code of ethics has generally required interpreters to interpret in direct speech (Pöchhacker 2004: 151). This practice has been incorporated in professional training to help interpreters achieve adequate interpreting (Hale 2007). The distinction between the two interpreting styles seems to be clear and straightforward. However, research has shown that interpreting service users may frequently engage ad hoc untrained interpreters who are unaware of this ethical requirement (Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005; Xu 2021). Sometimes, professionally trained interpreters may also deviate from the direct style to advance various goals (Cheung 2012; Gallez and Maryns 2014). These observed deviations, whether intentionally or unknowingly, have important implications for the interpreters’ understanding of their role, their stance towards the speakers and their level of professionalism (for example, Bot 2005; Cheung 2012; 2014; Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005; Van de Mieroop 2012).

Based on data taken from an ethnographic study of interpreted lawyer-client interviews in Australia, this study looks into the ways in which community interpreters choose their interpreting style, the reasons behind the interpreters’ choice and the implications for their role performance in an interactional context. Given that interpreter’s behaviour is closely related to their professional qualifications (Hale, Goodman-Delahunty, et al. 2020; Xu 2021), their interpreting style choice will be examined in relation to their training levels to explore the impact of training on interpreter’s performance. The findings of the study will be helpful in terms of guiding practice and informing policy making and training.

Following this introduction, Section 2 provides a review of relevant studies examining interpreter’s use of direct versus reported speech during interpreting, and discusses the association between an interpreter’s choice of interpreting style and their ethical role. Section 3 introduces the relevant setting of the study, that is, interpreted lawyer-client interviews; explains the methodological approach; and describes the data used in the study. Section 4 reveals the patterns of interpreters’ interpreting style choice in lawyer-client interviews and discusses their correlations with interpreter’s professional qualifications. Section 4 also examines occasions when interpreters temporarily shift between the two interpreting styles and explores the implications of this shift for interpreters’ role performance and their understanding of professional ethics. Section 5 summarises the findings of the study and points to limitations and potential directions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1 The interpreter’s choice of interpreting style: direct versus reported speech

Interpreting in direct speech style has traditionally been supported by legal professionals who work in courtroom settings to ensure the admissibility of interpreted evidence (Colin and Morris 1996). This is because in a courtroom, any information that is obtained second-hand is considered hearsay and thus cannot be used as evidence. Ng (2013: 250) has argued that the strict prescription of direct speech style “helps obscure the interpreter’s presence” so that the interpreter becomes an inactive “non-person” and “the problem of hearsay evidence is solved.” Therefore, from a jurisprudential point of view, interpreting style as a reflection of interpreter role becomes more of “a matter of legal admissibility” (Roberts-Smith 2009: 14) than having its own professional legitimacy. However, in a study of bilingual courtrooms in Belgium, Gallez and Maryns (2014) analysed a case in which an interpreter, when interpreting a judge’s request, switched to reported speech to highlight authorship of the utterance, thus adding to the illocutionary force of the request. Similar cases have also been reported in medical settings where interpreters shift to the third person to create some distance from what the speaker has said. This often takes place in face-threatening situations, such as when a doctor delivers bad news to a patient (Van de Mieroop 2012: 111), or when the interpreter doubts whether the patient has provided a “satisfactory” answer to the doctor’s question and chooses to use reported speech to disclaim responsibility for potential interactional problems (Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005: 221-223).

On a different note, apart from participant-related reasons, interpreters also use reported speech to manage the discursive process and facilitate interpreted exchanges. One of the most frequently reported situations where interpreters use the third person is to identify different speakers, sometimes including themselves (Cheung 2012; Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005; Van de Mieroop 2012). Cheung (2012: 79) shows that court interpreters in Hong Kong used reported speech to identify their own voice or make a distinction between different speakers to help new witnesses become familiar with court proceedings. Van de Mieroop (2012) labelled this practical use of reported speech as having a “disambiguating function.” In her study of medical interpreting, an interpreter, who was a semi-professional, sometimes deviated “from the normal pattern of translating turns” and initiated her own questions to the ongoing interaction (2012: 109). In order to distinguish her own words from those of the patient, the interpreter often used the third person to refer to the patient, aiming at “identifying the principal of the words, and the status of a translation” (Van de Mieroop 2012: 111). In addition, in remote interpreting, interpreters may also switch to reported speech to clarify the authorship of different utterances due to a lack of visual cues (Xu, Hale, et al. 2020).

The findings of the above studies are undeniably significant in describing and accounting for interpreters’ choice of interpreting style. Such findings are also revealing in understanding occasions when the interpreter’s role performance shows discrepancies, a point which, however, has been largely neglected in previous research. The next sub-section discusses the relations between the interpreter’s interpreting style choice and their ethical role.

2.2 Interpreting style choice and the interpreter’s ethical role

Interpreters’ codes of ethics worldwide generally stipulate that an ethical interpreter should provide accurate interpretation without adding or omitting anything, remain neutral and keep what is interpreted confidential (Hale 2007: 107). From an ethical point of view, the very rationale behind the direct speech norm is thus linked to the interpreter’s professional role. In other words, the interpreter’s ability to provide a faithful and unbiased interpretation is key to creating the illusion of direct communication (Wadensjö 1997: 49). In this sense, the direct speech norm indicates the “direct approach” of interpreting, that is “an interpreter renders each turn accurately from one speaker to the other, leaving the decision-making to the authors of the utterances” (Hale 2007: 42). Seen from this perspective, interpreters’ use of direct speech indicates their compliance with the code of ethics, which relies not only on a sound knowledge of the ethical principles but also on their competence in initiating active coordination (Hale 2007; Tebble 2012; Xu 2021). Therefore, the direct speech norm does not in any sense imply that interpreters have only a “shadowy presence” or that the interpreter is an “inactive non-person,” views taken by many legal professionals (Ng 2013; Roberts-Smith 2009).

When interpreters’ choice of interpreting style is understood in relation to their professional ethics, then their adoption of reported speech to create a distancing effect between themselves and the interpreted words and thus to disclaim personal responsibility (for example, Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005; Van de Mieroop 2012) may indicate a deviation from their neutral position. As a group of professionals, interpreters are only responsible for achieving accurate interpretation rather than for its content. Using direct speech implies no indication that the interpreters are involved in the content of the utterance and hence have become an author or principal in the interaction. Similarly, Bot (2005) viewed the interpreters’ distancing act as a “paradox.” She argued that “while interpreters add the ‘s/he says’ formulation to stress their role as a ‘mere conveyor of the message,’ the very addition is in itself a deviation from the strict conveyor model” (2005: 224).

It is also worth pointing out that the direct speech style does not suggest a total rejection of the use of reported speech or change in person perspective during interpreting. When interpreters need to initiate coordination of the interaction by drawing upon a repertoire of management strategies, such as asking for repetitions, instructing the speakers to follow turn-taking rules (Hale, Goodman-Delahunty, et al. 2020; Tebble 2012), they need to speak as themselves and potentially shift to reported speech (Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005). Although the use of reported speech may enjoy superiority over direct speech in making “the attribution of the interpreted utterances explicit” (Cheung 2014: 195), the extent to which interpreters use this style to coordinate the interaction should be carefully managed in consideration of their professional ethics and the outcome of their intervention. Bot (2005: 251), focusing on medical interpreting, cautions that the use of indirect interpreting is likely to lead to “a narrative style in which he (the interpreter) talks about the patient.” One example is found in Van de Mieroop’s (2012) study of an interpreted medical consultation: when the interpreter added her own question to help the patient acquire more explanation from the doctor, she shifted to the third person to refer to the patient to distinguish her own initiated question from that of the patient’s. Such use of reported speech can be seen as a “mediated approach” of interpreting, which “argues for an interpreter who does not interpret for two main participants, but who mediates between them, deciding on what to transmit and what to omit from the speakers’ utterances” (Hale 2007: 42). When interpreters use reported speech to “mediate” between speakers, it is likely to represent a breach of their professional ethics (Hale 2007: 107; Tebble 2012).

Furthermore, adherence to the direct speech style is often linked to the professional image of interpreters (Bot 2005; Cheung 2012). Such a claim, however, lacks empirical support. Few previous studies have examined the interpreters’ interpreting style choice in relation to their professional qualifications. Some researchers remain vague about the interpreters’ qualifications (for example, Ng 2013) or have focused on amateur interpreters (Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005) or semi-professional interpreters who may have some knowledge of interpreting, but have not undergone systematic training or become professionally accredited (Bot 2005; Van de Mieroop 2012). In light of the scarcity of research in this area, one may wonder how interpreters’ professional qualifications are likely to impact on their choice of interpreting style.

3. The study

3.1 The setting: interpreted lawyer-client interviews

The present study looks into interpreters’ choice of interpreting style in lawyer-client interviews, an interpreting setting that has been rarely researched. To this date, research into the practice of interpreting in legal settings has been mainly based on courtroom scenarios (for example, Berk-Seligson 2002; Hale 2004). This research trend does not reflect the reality that most of people’s legal problems are resolved outside of a courtroom. In particular, “a significant and growing amount of rights enforcement takes place in less formal lawyering settings” (Ahmad 2007: 1010). Such “less formal lawyering,” which often takes the form of lawyer-client interviews conducted in a confidential setting, is widely seen as having become a major component of people’s experience in the legal sphere (Hosticka 1979). During the course of an interview, clients’ “real-world” problems are interpreted and transformed into rule-oriented accounts by the lawyers in terms of legal rules and categories (Maley, Candlin, et al. 1995). As crucial as these interviews are in helping clients understand their matter through a legal lens, not many studies exist to investigate this type of professional-lay legal encounter due to issues of confidentiality (Howieson and Rogers 2019). Even less research has been undertaken to identify the issues existing when these legal interviews are conducted in a multilingual context.

The few existing studies of interpreted lawyer-client interviews reveal interpreters as “third parties” full of subjectivity who often very actively engage with lawyers and clients, sometimes even beyond their conventional role boundaries (Ahmad 2007; Inghilleri 2013; Xu 2021). Interpreters have been found to assume a number of extra communication tasks, such as adding their own comments and opinions, filtering information or posing questions (Ahmad 2007; Inghilleri 2013; Xu 2021). Ahmad (2007: 1003), based on an observation of an untrained interpreter’s performance in a legal advice meeting in the US, argued that lawyers should “accept the interpreter as a partner rather than rejecting her as an interloper, by resolving the dynamic of dependence and distrust in favour of collaboration” in order to enhance the voice of their multilingual clients. Contextualising her study in the UK asylum application process, Inghilleri (2013) showed that the immigration lawyers and interpreters worked in partnerships that extended beyond those envisioned in interpreter’s professional ethics, evidenced by interpreters’ active involvement in helping lawyers elicit information from the clients.

An expansion of the interpreter’s normative role in facilitating lawyer-client communication (Ahmad 2007; Inghilleri 2013) seems to indicate a “mediated approach” of interpreting (Hale 2007), yet how such intervention on the part of the interpreter is likely to impact on the dynamics of the lawyer-client interaction, as well as its implications for the interpreters’ role performance and professionalism, are issues that have not attracted much attention in previous research. A recent study of interprofessional relations between legal aid lawyers and interpreters in Australia shows that interpreters’ interventions may not always achieve the desired outcome (Xu 2021). Based on a survey of 25 lawyers, Xu (2021) reveals that the lawyers strongly opposed interpreters taking on roles that were not stipulated in their code of ethics. Moreover, it is noticeable that data used in previous research were obtained from an isolated case of a single interpreter’s performance (Ahmad 2007) or through retrospective accounts by lawyers and interpreters (Inghilleri 2013). There are few observational studies to identify any recurring pattern of interpreter’s practice and triangulate results with those obtained from interviews.

3.2 The methodology: An ethnographic approach

The present study takes an ethnographic approach to examine the style adopted by interpreters in interpreted lawyer-client interviews. Originally developed in the discipline of anthropology, ethnography is defined as “the study of a social group or individual or individuals representative of that group, based on direct recording of the behaviour and ‘voices’ of the participants” (Hale and Napier 2013: 84). Ethnographic research methodologies have been widely used in interpreting studies to investigate a range of issues in different settings, such as the challenges faced by court interpreters in achieving accuracy (Berk-Seligson 2002) and the interpreter’s visibility in cross-lingual medical consultations (Angelelli 2004). These studies feature prolonged engagement between researchers and the research participants through fieldwork, a triangulation of data collected using different methods, direct observations of interpreters’ practice and interviews with interpreters about their work (Hale and Napier 2013: 93).

Given that the object of the present study, interpreted lawyer-client interviews, is a dynamic process of interaction between lawyers, interpreters and clients occurring in a specific social context, with a range of linguistic and cultural factors shaping its process and outcome, ethnographic research tools are suitable for an exploratory study investigating this rarely researched setting (Flynn 2010; Hale and Napier 2013). To depict the ways in which interpreters choose their interpreting style, the author conducted participant observation. Considering the shaping force of researchers’ own backgrounds, knowledge and values in the course of generating data and presenting results, participant observation needs to be a recursive process involving much “critical reflexivity of self” (Cho and Trent 2006; Flynn 2010; Yu 2020). Therefore, while observing interpreters’ practice in lawyer-client interviews, it is critical that the author have “an open mind” (Angelelli 2015) and constantly reflect how her position as a researcher is likely to impact on the data collection and analytical approaches (Flynn 2010; Yu 2020). Meanwhile, to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings of an ethnographic study, a triangulation of data obtained from different resources is often used as an effective control mechanism (Hale and Napier 2013; Yu 2020). In the present study, the author interviewed the interpreters after the observation to triangulate the findings of the post-observation interviews with those of the observation.

3.3 The data

Between March and November 2016, the author conducted fieldwork at the Legal Aid Commission in the State of New South Wales (Legal Aid NSW), Australia. Altogether, the author observed 20 authentic interpreted lawyer-client interviews and carried out post-observation interviews with 12 interpreters.

Legal Aid NSW is a publicly funded organisation that provides affordable legal services to financially disadvantaged people in New South Wales. In order to help clients who speak a language other than English (LOTE) to access services, Legal Aid NSW engages interpreting services from external interpreting agencies and requires that interpreters be accredited by NAATI to ensure interpreting quality (Legal Aid NSW 2014).[1] In Australia, NAATI accredited interpreters working in community-based settings need to adhere to the AUSIT Code of Ethics (AUSIT 2012; Tebble 2012). The Code stipulates that interpreters should always provide accurate interpretation, remain neutral, maintain clear role boundaries and refrain from engaging in tasks such as advocacy, guidance or advice (AUSIT 2012). The Code also prescribes that interpreters should interpret in the first person (AUSIT 2012: 14). Legal Aid NSW provides guidelines to lawyers on how to work with interpreters. The guidelines support interpreters’ compliance with the AUSIT Code of Ethics. In terms of the lawyer’s speech style, the guidelines recommend that lawyers should speak directly to the client in the first person and avoid expressions such as “tell him…” or “does she understand” (Legal Aid NSW 2014: 9).

The author carried out these observations at the Head Office of Legal Aid NSW in the Central Business District (CBD) of Sydney. Consents were obtained from all the research participants prior to the observations. The observations aimed to identify interaction patterns between lawyers and interpreters in English, as well as the language(s) used by the lawyers to conduct the interviews and communicate with the interpreters. Due to confidentiality requirements, the author was not allowed to record the interviews using any audio or video recording equipment. The author took handwritten notes using an observation sheet which listed a set of themes that had been extracted from the academic literature to systematize the observations. These themes were used to reflect different aspects of lawyer-interpreter interaction, such as their greetings, briefings, interpreting style choice, turn-taking management and interpreter’s role performance.

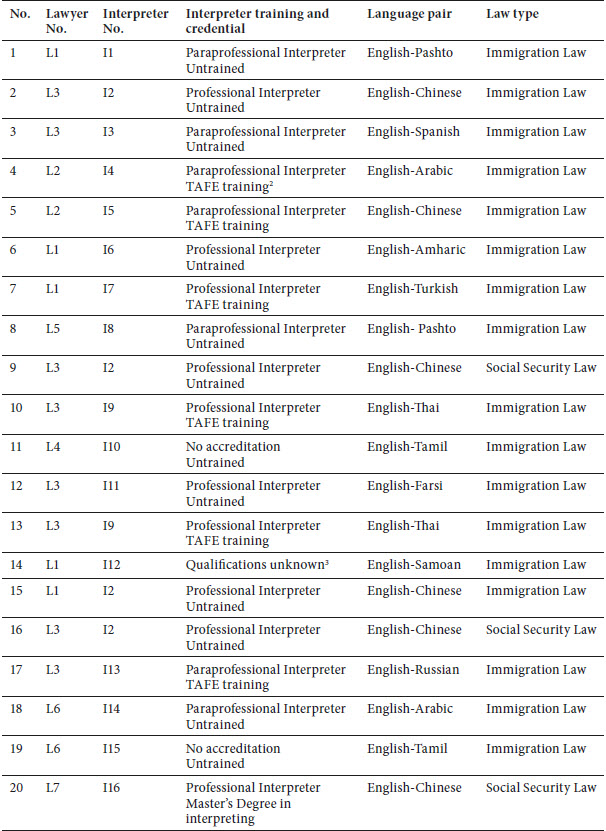

The 20 observed interviews involved a total of eight lawyers, 16 interpreters and 20 clients who spoke 11 different languages. Detailed information on the 20 interpreted interviews, including language pair, law type and the interpreters’ training and accreditation levels is provided (see Table 1). All eight lawyers were full-time staff working at Legal Aid NSW. The 16 interpreters were accredited at different levels, with only six of them having received professional training. The mix of interpreters with different training and accreditation levels was due to practical reasons. In Australia, NAATI accreditation is not available for all the languages for which there is a need for interpreting services and systematic interpreting training at a tertiary level is only available for a limited set of languages.

Twelve interpreters participated in the interviews. Out of the 12 interpreters, the author conducted observations on ten of them. For the remaining two interpreters, their clients did not give consent for their sessions to be observed, but the two interpreters agreed to be interviewed afterwards. The interviews were semi-structured and each lasted for about twenty minutes. The interview questions were developed based on the results of the observation. The interpreters were asked to comment on specific aspects of their interaction with the lawyers, such as how they were briefed by the lawyers, how they managed turns, which interpreting style they used and why as well as how they perceived their role. With the consent of the interpreters, the interviews were recorded using digital audio equipment.

The present study only reports on findings related to the interpreters’ interpreting style choice.

Table 1

An Overview of the 20 Interpreted Lawyer-Client interviews[2][3]

4. The results and discussion

This section presents the findings of the study. Section 4.1 introduces the 16 interpreters’ choice of interpreting style in relation to their professional qualifications. Section 4.2 concentrates on examining the occasions when interpreters temporarily switched to reported speech and discusses the implications of this for the interpreters’ role performance.

4.1 The interpreters’ interpreting style choice and their professional qualifications

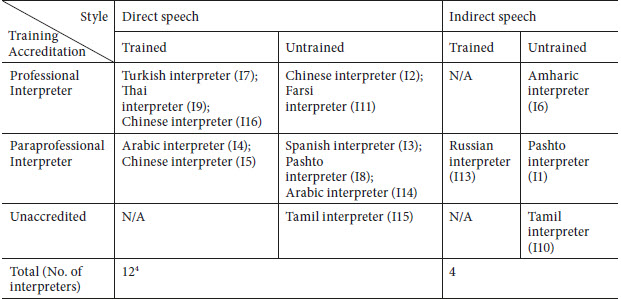

The observations show that 12 of the 16 interpreters adhered to the norm of direct speech by interpreting in the first person, that is in the speaker’s role, except for occasional deviations. Their practice complied with ethical requirements (AUSIT 2012: 14). Four interpreters stood out for their exclusive use of reported speech; that is, they always used the third person to refer to the speakers during interpreting. The four interpreters were an Amharic interpreter (I6), a Pashto interpreter (I1), a Russian interpreter (I13) and a Tamil interpreter (I10).

When the 16 interpreters’ choice of interpreting style was analysed in accordance with their training and accreditation levels (see Table 2), it was found that all but one (I13) of the six trained interpreters interpreted in direct speech. The four interpreters who habitually used reported speech represented a lower level of professional qualifications: only the Amharic interpreter was accredited as a Professional Interpreter; both the Russian and the Pashto interpreters were Paraprofessional Interpreters; the Tamil interpreter had no NAATI accreditation; and none of these four interpreters had received any training except for the Russian interpreter who had undertaken TAFE training 15 years prior. These results point to a link between interpreters’ choice of interpreting style and their professional qualifications: trained interpreters were more likely to adhere to the direct interpreting style whilst interpreters who were untrained and accredited at a lower level tended to breach the ethical norm by using reported speech. This finding is consistent with a recent study of simulated interpreted police interviews where researchers found that trained interpreters are more capable of meeting ethical requirement in terms of their ability to achieve pragmatic accuracy (Hale, Goodman-Delahunty, et al. 2020).

Table 2

Interpreters’ Choice of Interpreting Style and Their Professional Qualifications[4]

Among the four interpreters who habitually used reported speech, the author interviewed the Tamil interpreter (I10) and the Russian interpreter (I13). Neither of the two interpreters realised that their interpreting style contravened the ethics of professional practice. When asked why they used reported speech in interpreting, the Tamil interpreter (I10) explained that it was because the lawyers and the clients often spoke indirectly (see Quote 1). This point was also raised by a Farsi interpreter (I11) who confirmed her use of direct interpreting style, but also added that on some occasions the lawyers talked to the interpreter directly rather than to the clients (see Quote 2). These comments seem to reveal that not all the legal aid lawyers consistently used direct speech as recommended in the guidelines and their choice of speech style had an impact on the interpreter’s choice of interpreting style. Considering the asymmetrical lawyer-client working relations in which interpreters tend to feel they are inferior to the lawyers in terms of professional status (Xu 2021), interpreters may just rely on reported speech to accommodate the lawyer’s use of reported speech.

Quote 1: “Because she, the legal professional was asking ‘What did they say?’. So I answer them ‘They said… They are thinking…’. That’s what I’ve been doing. Even the clients would say ‘Can you ask them…’, ‘Can you ask she [sic]…’. So how do I say that?”

I10

Quote 2: “First [person], it has to be… But some solicitors sometimes, very rarely, talk to me rather than the client. Ask him if this is this and this.”

I11

The Russian interpreter (I13) did not explain why she adopted the indirect interpreting style, but made a comment about the interpreter’s role, which she believed was just that of a machine (see Quote 3). Similarly, another Tamil interpreter (I15) stated that he interpreted in the first person because he was a mouthpiece of the client (see Quote 4). This Tamil interpreter was untrained, but adhered to the direct speech norm. By comparing the interpreter’s role to a machine or a mouthpiece, these two interpreters (I13 and I15) seemed to highlight the interpreter’s non-involvement (Wadensjö 1998/2014), albeit in a passive way. The Tamil interpreter also stated that to act as a mouthpiece, he needed to “express the way [sic] literally what the client said.” Such a perception indicates a word-for-word approach to interpreting, which, however, is not the way to achieve accuracy (Hale 2004). Numerous studies have shown that rather than assuming an invisible mouthpiece role and acting in a mechanical manner, interpreters are highly visible participants who are capable of initiating active coordination to facilitate communication across languages (Angelelli 2004; Hale, Goodman-Delahunty, et al. 2020). Considering that the Tamil interpreter (I10) lacked proper training, despite his compliance with the norm in practice, it seems that he did not have adequate knowledge of the interpreter’s professional role to truly understand the rationale behind the direct speech norm.

Quote 3: “Just a machine… It’s very hard to do it.”

I13

Quote 4: “We are encouraged to be the mouthpiece of the clients. In other words, you basically express the way [sic] literally what the client said. You act as the mouthpiece of the clients so you have to talk in the first person rather than saying ‘he says…’ or ‘she says…”

I15

In comparison, trained interpreters justified their choice of direct speech by reference to the code of ethics, indicating that their capability to adhere to this norm is premised on a sound knowledge of professional ethics. This is shown in Quote 5 where an interpreter stated that she learnt to interpret directly from training and the direct interpreting style made it easier to achieve accuracy, helped her remain neutral and promoted direct communication between the lawyers and the clients.

Quote 5: “From training. I think it’s very important because if you use the third person, it doesn’t sound like you are talking. It’s like you are saying someone’s words. But if you talk in the first and the second person, firstly, grammatically, it’s easier. You don’t need to think about the verbs. How to change them. And then it’s more natural, when you are talking in their voices. And also thirdly, it’s about encouraging the actual clients to communicate with each other instead of communicating through the interpreter or with the interpreter.”

I16

4.2 Interpreters’ occasional deviation from the direct interpreting style

The 12 interpreters who adhered to the direct speech norm were nevertheless observed to switch to reported speech at several points in the interviews. These occasions took place when interpreters felt the necessity to clarify the authorship of different speakers, when they added comments, when they attempted to distance themselves from the interpreted utterance or when they made direct replies to the lawyers’ queries. Some of these instances reflect the interpreters’ active coordination of the interactive encounter whilst others indicate interpreters’ adoption of roles that are not covered under the code of ethics. Noticeably, interpreters who shifted to reported speech to assume extra communication tasks were those who had not undergone professional training. The post-observation interviews further reveal that these untrained interpreters often had misconceptions about some aspects of the interpreter’s professional role and ethics. This section will use selected examples to show the circumstances under which interpreters temporarily deviated from the normative interpreting style of direct speech and analyse the implications of such deviations for their role performance.

In Example 1 above, an Arabic-speaking woman was enquiring about applying for a visa for her mother to come to Australia. The woman was accompanied by her husband. The interview was interpreted by an untrained Paraprofessional Interpreter (I14). At this point, the lawyer (L6) asked the couple where they lived. Both the client and her husband started to speak at the same time. When rendering their answers, the interpreter started by speaking in the first person (“we”), meaning the client’s words. Then the interpreter introduced a third person reference (“her husband”) and a reporting verb (“said”), indicating that what followed was from the client’s husband.

It was common for legal aid lawyers to engage with multiple LOTE speakers at a time because many clients are accompanied by family members or friends. The observations show that these extra LOTE speakers frequently intervened in the ongoing conversations and volunteered their knowledge of the case. Rather than initiating a new turn when the floor was open, they often talked during the clients’ turn, resulting in overlapping speech. This means interpreters needed to interpret for more than one speaker within one turn of interpretation, which validates their use of reported speech to clarify the authorship of different utterances. This finding is in line with the result of earlier studies which suggests that on certain occasions reported speech may be more suitable for interpreters to manage the interpreted encounters (Cheung 2012; Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005; Van de Mieroop 2012).

Example 2 below shows the interpreter (I14) shifted to reported speech again, but this time to achieve a different purpose.

When the interview was almost finished, the client initiated a new question, asking the lawyer if she could visit a Legal Aid NSW office that was near her place. The lawyer suggested that she could visit Liverpool or Bankstown Legal Aid Offices. After hearing the lawyer’s suggestion, the client exchanged a few turns of talk with her husband in Arabic. Instead of interpreting to the lawyer what the client and her husband said, the interpreter turned to the lawyer and made a comment about the situation, as shown in Example 2. In this line, the interpreter used the third person pronoun (“she”) to refer to the client, whereas the first person (“I”) meant the interpreter herself. The use of the third person reference made it clear that the interpreter was talking about the client rather than repeating what she said. By adding her own point of view to the ongoing conversation, the interpreter was interpreting in the “mediated approach” (Hale 2007: 41-43), through which the interpreter seemingly “helped” the lawyer to understand the client’s situation. The interpreter’s temporary shift implies her deviation from the neutral position and adoption of a role that is not stipulated in the code of ethics (Cheung 2014; Van de Mieroop 2012). Such practice echoes the findings of previous research that reveal the interpreter’s active involvement in lawyer-client interaction (Ahmad 2007; Inghilleri 2013; Xu 2021). However, the interpreter’s intervention interfered with the direct communication between the lawyer and the client (Tebble 2012) and the lawyer never had a chance to hear what the client and her husband had said.

Example 3 below shows another case of an interpreter shifting to reported speech to assume a helper role in the ongoing interview.

Example 3 is drawn from Interview No. 12 where a Farsi-speaking client was enquiring about how to help her sister, Rosi, who lived in Iran, migrate to Australia. At this moment, the lawyer (L3) attempted to call Rosi to ask some questions about her status in Iran. However, the number she found from the documents was actually the client’s number. Therefore, each time she dialled the number, the client’s mobile phone rang, but the lawyer did not realise this. So the interpreter (I11) intervened by addressing the lawyer directly, as signalled by her use of the third person (“her”) to refer to the client, to explain the misunderstanding. After that, the interpreter also asked the lawyer whether she wanted Rosi’s number, to which the lawyer gave a positive reply. This example shows that the interpreter’s shift to the third person reference was out of an intention to help the lawyer clarify the confusion, which, however, is a deviation from the neutral position. A similar case was reported by Hale (2008) in court interpreting where an interpreter alerted the lawyer that the lawyer had made a mistake about two people’s surnames. According to Hale (2008), an ethical way would be for the interpreter to interpret the mistake and thus let the lawyer and the witness resolve the issue by themselves.

The interpreter in Example 3 was an untrained Paraprofessional Interpreter who was interviewed by the author after the observation. This interpreter was aware that an interpreter should be an impartial party whose role was to provide accurate rendition without interfering in the interpreted exchanges (see Quote 6). The interpreter also added that she was not in a position to help the clients by giving them advice or correcting them (see Quote 7). These perceptions comply with what is required in the code of ethics (AUSIT 2012). Yet, at the same time, the interpreter admitted that when being asked by the lawyers to comment on the clients, she usually told them her “honest opinions” (see Quote 8). This seems to indicate that in spite of the interpreter’s emphasis on impartiality, she did not have a clear understanding of the meaning and implications of this ethical principle. The interpreter was biased in favour of the lawyers by being more concerned with satisfying their needs without realizing this was in itself a breach of the code of ethics.

Quote 6: “Just being impartial. Interpret exactly whatever each person says… I mean I don’t interfere. I don’t get involved.”

I11

Quote 7: “We are not there to help them (clients) to give them advice or correct them (clients), if they (clients) say something they shouldn’t.”

I11

Quote 8: “They (lawyers) wanted to talk more and to know my idea of the clients’ situations… Because some of them (clients), they have been activists. They are political… Because from that region I should know activism is so popular, or the political figure that should be well known. They (lawyers) asked me if I know this person. ‘Do you think he’s right?’ ‘Do you think he’s just making the story?’ I tell them (lawyers) my honest opinion”

I11

The following example shows a face-threatening situation, where an untrained interpreter switched to reported speech to disassociate himself from the interpreted utterance.

Example 4 above is drawn from Interview No. 16 where a Chinese-speaking client was seeing a lawyer (L3) enquiring about a social security matter. At this point, the lawyer asked the client about her legal problem. Instead of providing a direct answer, the client took from her bag several packages of medicine and documents and piled them all over the interview desk. Seeing the client’s behaviour, the lawyer frowned and told the client that there was no need for her to bring the documents because she had them already, indicating that the client could remove the medicine and the documents away. However, the client explained through the interpreter that she had prepared a script, which was among these documents and which she intended to read to the lawyer to describe her legal problem.

The lawyer-client relationship, as in most professional-lay encounters, tends to be asymmetrical in terms of power (Bogoch 1994). In Example 4, the client’s lack of action to the lawyer’s instructions posed a threat towards the lawyer’s authority, constituting a face-threatening act. When rendering the client’s reply, the interpreter was rather hesitant and temporarily switched to the third person (“she”) to refer to the client. In this way, the interpreter reported what the client said and avoided assuming the same voice as the client, highlighting that the face-threatening utterance was from the client. Yet, by attempting to create a distancing effect (Berk-Seligson 2002; Dubslaff and Martinsen 2005; Van de Mieroop 2012), the interpreter deviated from the neutral position because he associated himself with the client’s previous utterance. As previously discussed, interpreting in the first person would not have made the interpreter responsible for the content of the interpreted utterance, as it would have been clear that as a professional, his ethical role was to “relay” whatever the client had said.

Further, what is also worth noting in Example 4 is that the interpreter’s deviation had an impact on the way in which the lawyer made her reply. In response to the interpreted utterance, the lawyer, who had maintained the direct speech style consistently, also shifted to indirect speech. The lawyer’s shift seemed to be prompted by the interpreter’s change, corroborating what was found in Dubslaff and Martinsen’s (2005) study of a simulated interpreted medical consultation: an interpreter’s shift in the choice of address can trigger a change in the speech style of the doctor. Yet, considering the content of the lawyer’s utterance, her shift may also serve another function. Clearly, the lawyer was not happy with the client’s plan and suggested a different approach. Because the lawyer’s reply was face-threatening towards the client, she shifted to the third person to refer to the client and made the interpreter her direct addressee.

The excerpt below shows another case where a lawyer shifted to reported speech to avoid a face-threatening act towards the client and demonstrates the impact of this shift on the interpreter’s choice of interpreting style and its associated interpreting approach.

Example 5 is drawn from Interview 15 where a Chinese-speaking client was enquiring about how to extend her stay in Australia through a new visa. At the start of the interview, the client described how she had suffered from domestic violence at the hands of her husband. However, as the client was very emotional, her account, when interpreted into English, sounded unclear and incoherent. At this moment, the lawyer addressed the interpreter directly to express her confusion rather than speaking to the client directly to clarify her account. The lawyer may have meant that the client’s utterance was unclear or else implied that it was the interpreter’s inadequate interpretation that created a difficulty in understanding the client. In the former case, the lawyer’s practice could have intended to avoid a face-threatening act towards the client. Accordingly, the interpreter needed to decide whether he should relay the lawyer’s utterance to the client or provide another “clearer” interpretation.

As shown in Example 5, the interpreter shifted to reported speech and replied to the lawyer directly. Ostensibly, the interpreter’s shift was induced by the lawyer’s change of speech style. Yet, the underlying reason may be attributed to the interpreter’s understanding of his role at that moment. The interpreter in the post-observation interview stated that his role as an interpreter was just to convey messages between two parties (see Quote 9). Yet, he also revealed that on occasions when the speakers did not “speak logically,” he needed to modify the utterance to “get the message across” (see Quote 10).

Quote 9: “You see, I just interpret between two parties. When a party says something, I interpret what he or she says to the lawyer.”

I2

Quote 10: “Well, just somebody who can come to their assistance… When some people don’t speak logically, I have formed my sentences for them to get the message across.”

I2

The interpreter thus chose to report what the client had said in a summarized polished version to “assist” the client to express herself. However, the interpreter’s deviation from the normative interpreting style and adoption of an advocate role deprived the client of direct and full participation in the interview (Tebble 2012). The client was temporarily excluded from the interpreted interview where she was supposed to be a valid participant and have her own input. Given that the interpreter’s shift to reported speech and its consequent deviation from normative role performance had to do with the lawyer’s change of addressee, it indicates that the lawyer’s speech style had a significant influence on the interpreter’s choice of interpreting approach and performance of role, providing corroborative evidence for the Tamil interpreter’s comment (see Quote 1) in Section 4.1. It also reinforces the importance of lawyers addressing their client directly rather than going through the interpreters (Legal Aid NSW 2014).

5. Conclusion

Relying on data obtained from authentic interpreter-facilitated lawyer-client interviews, a little researched area in interpreting studies, the present study has examined interpreters’ interpreting style choices as reflected in their interaction with lawyers. The findings have shown that using direct speech during interpreting is more than just a simple interpreting style that interpreters can choose to adopt or disobey according to their preference. What lies behind this style choice is the interpreters’ understanding of their role and professional ethics. Interpreters who had undergone professional training adhered to the normative direct interpreting style and were able to justify their choice from an ethical perspective, demonstrating sound knowledge of the interpreter’s professional ethics. In comparison, untrained interpreters were more likely to have difficulty in using direct interpreting style consistently. They shifted to reported speech to achieve a range of purposes other than interpretation, which suggests their adoption of roles extending beyond the interpreter’s ethical role boundaries. These deviations related to the untrained interpreters’ misconceptions about some aspects of the interpreter’s professional role and ethics.

The present study has a number of limitations. As the author was not able to digitally record the interviews and mainly relied on hand-written observation notes, only limited aspects of the interpreted lawyer-client encounters were noted, which confined the scope of the study and the breadth of the data. In addition, although the coverage of a wide range of languages can be considered as a strength of the data set, which reflected a genuine need for interpreting services at Legal Aid NSW, it inevitably limited the data analysis approaches. The present study has only examined interpreters’ interpreting choice in one direction, namely from LOTE to English. Further language-specific study is required to investigate how interpreters perform in the other direction and to compare the interpreters’ performance in both directions to explore how their choice of style is affected by other factors, such as cultural differences and interpreter’s linguistic proficiency. Nevertheless, the present study is among the first to investigate interpreted lawyer-client interviews based on observation of authentic cases over a prolonged period of time. It is hoped that the findings of the present study will generate research interest in this area and yield useful information to inform training and practice.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

NAATI is the interpreting and translation accreditation authority in Australia. At the time when the study was conducted, there were four accreditation levels for interpreting, including Senior Conference Interpreter, Conference Interpreter, Professional Interpreter and Paraprofessional Interpreter. To obtain a NAATI accreditation, training was not compulsory and a prospective interpreter only needed to pass an examination.

-

[2]

Since 2018, NAATI has launched a new certification system, adding new categories of specialist interpreters (in legal and healthcare settings) and making pre-service training compulsory. See <https://www.naati.com.au>.

-

[3]

Technical and Further Education (TAFE) is the primary vocational education and training provider in Australia. TAFE offers interpreting and translation for Advanced Diploma, Diploma and short courses in some languages.

-

[4]

The Samoan interpreter chose to not reveal her training and accreditation levels. The 12 interpreters included the Samoan interpreter, but she is not listed in the table because her professional qualification was unknown.

-

[5]

“Transcript” is used here by mistake instead of “script.”

Bibliography

- Ahmad, Muneer I. (2007): Interpreting Communities: Lawyering across Language Difference. UCLA Law Review. 54:999-1086.

- Angelelli, Claudia (2004): Medical interpreting and cross-cultural communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Angelelli, Claudia (2015): Ethnographic Methods. In: Nadia Grbic and Franz Pöchhacker, eds. Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies. London: Routledge, 148-150.

- AUSIT (2012): AUSIT Code of Ethics and Code of Conduct. Accessed 18 June 2020. https://ausit.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Code_Of_Ethics_Full.pdf.

- Berk-Seligson, Susan (2002): The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the judicial process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bogoch, Bryna (1994): Power, distance and solidarity: Models of professional-client interaction in an Israeli legal aid setting. Discourse and Society. 5(1):65-88.

- Bot, Hanneke (2005): Dialogue interpreting as a specific case of reported speech. Interpreting. 7(2):237-261.

- Cheung, Andrew K. F. (2012): The use of reported speech by court interpreters in Hong Kong. Interpreting. 14(1):73-91.

- Cheung, Andrew K. F. (2014): The use of reported speech and the perceived neutrality of court interpreters. Interpreting. 16(2):191-208.

- Cho, Jeasik and Trent, Allen (2006): Validity in qualitative research revisited. Qualitative Research. 6(3):319-340.

- Colin, Joan and Morris, Ruth (1996): Interpreters and the legal process. Winchester: Waterside Press.

- Dubslaff, Friedel and Martinsen, Bodil (2005): Exploring untrained interpreters’ use of direct versus indirect speech. Interpreting. 7(2):211-236.

- Flynn, Peter (2010): Ethnographic Approaches. In: Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies: Volume 1. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 116-119.

- Gallez, Emmanuelle and Maryns, Katrijn (2014): Orality and Authenticity in an Interpreted-mediated Defendant’s Examination. A Case Study from the Belgian Assize Court. Interpreting. 16(1):49-80.

- Hale, Sandra(2004): The discourse of court interpreting: Discourse practices of the law, the witness, and the Interpreter. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hale, Sandra (2007): Community interpreting. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hale, Sandra (2008): Controversies over the role of the court interpreter. In: Carmen Valero-Garces and Anne Martin, eds. Crossing borders in community interpreting: Definitions and dilemmas. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 99-121.

- Hale, Sandra, Goodman-Delahunty, Jane and Martschuk, Natalie (2020): Interactional management in a simulated police interview: Interpreters’ strategies. In: Marianne Mason and Frances Rock, eds. The discourse of police investigation. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 200-225.

- Hale, Sandra, Martschuk, Natalie, Goodman-Delahunty, Jane, et al. (2020): Interpreting profanity in police interviews. Multilingua. 39(4):369-393.

- Hale, Sandra and Napier, Jemina (2013): Research methods in interpreting: A practical resource. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hosticka, Carl J. (1979): We don’t care about what happened, We only care about what is going to happen: Lawyer-client negotiations of reality. Social Problems. 26(5):599-610.

- Howieson, Jill and Rogers, Shane L. (2019): Rethinking the lawyer-client interview: taking a relational approach. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 26(4):659-668.

- Inghilleri, Moira (2013): Interpreting justice: Ethics, politics and language. New York: Routledge.

- Legal Aid NSW (2014): Guidelines on interpreting and translation. Accessed 22 June 2022. https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/5832/Guidelines-on-interpreting-and-translation.pdf.

- Maley, Yon, Candlin, Christopher, Crichton, Jonathan, et al. (1995): Orientation in lawyer-client interviews. Forensic Linguistics. 2(1):42-55.

- Ng, Eva (2013): Who is speaking? Interpreting the voice of the speaker in court. In: Christina Schaffner, Krzysztof Kredens and Yvonne Fowler, eds. Interpreting in a changing landscape: Selected papers from Critical Link 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 249-266.

- Pöchhacker, Franz (2004): Introducing Interpreting Studies. London/New York: Routledge.

- Roberts-Smith, Len (2009): Forensic interpreting: Trial and error. In: Sandra Hale, Uldis Ozolins and Ludmila Stern, eds. Critical link 5. Quality in interpreting: A shared responsibility. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 13-35.

- Tebble, Helen (2012): Interpreting or interfering? In: Claudio Baraldi and Laura Gavioli, eds. Coordinating participation in dialogue interpreting. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 23-33.

- Van De Mieroop, Dorien (2012): The Quotative “He/She Says” in Interpreted Doctor–Patient Interaction. Interpreting. 14(1):92-117.

- Wadesnjö, Cecilia (1997): Recycled information as a questioning strategy: Pitfalls in interpreter-mediated talk. In: Silvana E. Carr, Roda P. Roberts, Aideen Dufour, et al., eds. The Critical Link: Interpreters in the Community. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 35-52.

- Wadensjö, Cecilia (1998/2014): Interpreting as interaction. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Xu, Han (2021): Interprofessional relations in interpreted lawyer-client interviews: An Australian case study. Perspectives. 29(4):608-624.

- Xu, Han, Hale, Sandra and Stern, Ludmila (2020): Telephone interpreting in lawyer-client interviews: An observational study. Translation & Interpreting. 12(2):18-36.

- Yu, Chuan (2020): Ethnography. In: Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha, eds. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies (Third edition). London: Routledge, 167-171.

List of tables

Table 1

An Overview of the 20 Interpreted Lawyer-Client interviews[2][3]

Table 2

Interpreters’ Choice of Interpreting Style and Their Professional Qualifications[4]