Abstracts

Abstract

Conference signed language interpreters traditionally work between their national sign language and the national spoken or written language. During their careers, interpreters may add other spoken or signed languages to their repertoire. Some also acquire International Sign (IS) as a working language and interpret between IS and other signed and spoken languages. Being highly context dependent, IS has limited conventions and there is no established educational path toward learning to interpret IS. Generally, the acquisition of IS by any signer happens through interaction with signers of other signed languages. In this article, we explore the concept of IS conference interpreters as a Community of Practice (CoP), where novices acquire and experienced IS interpreters further their IS interpreting competences through situated learning. Such learning in practice may ultimately lead to the development of interpreting expertise and expert performance in IS conference interpreting. We present new data from a 2019 global survey of IS conference interpreters and follow-up interviews with eleven selected survey respondents. The results of our study suggest that there is indeed a CoP of IS conference interpreters and that it is essential for individual interpreters to participate in that community to develop the required competences and professional practices.

Keywords:

- conference interpreting,

- international sign,

- community of practice,

- competences

Résumé

Les interprètes de conférence en langue des signes travaillent traditionnellement entre leur langue des signes nationale et leur langue vocale nationale. Au cours de leur carrière, les interprètes peuvent ajouter d’autres langues de travail (écrites ou orales), qu’elles soient vocales ou signées. Certains ajoutent les signes internationaux (SI) comme langue de travail, et interprètent entre les SI et une langue vocale ou une autre langue signée. Hautement lié au contexte d’utilisation, les SI ont des conventions limitées, et il n’existe pas de formation officielle pour apprendre comment interpréter avec les SI. Généralement, l’acquisition des signes internationaux provient de l’interaction avec d’autres signants qui utilisent d’autres langues des signes. Dans cet article, nous examinons le concept d’interprète en signes internationaux en tant que communauté de pratique, où les novices apprennent, et les interprètes expérimentés renforcent leurs compétences par le biais d’un apprentissage situé. Cet apprentissage en pratique peut conduire au développement d’une expertise en interprétation et d’une expertise en interprétation de conférence avec les SI. Nous présentons de nouvelles données provenant d’une enquête internationale réalisée en 2019 à propos des interprètes de conférence SI, et des entretiens de suivi menés avec 11 participants. Les résultats de notre étude suggèrent qu’il existe effectivement une communauté de pratique d’interprètes de conférence SI et qu’il est essentiel pour les interprètes de participer à cette communauté pour développer leurs compétences et les pratiques professionnelles requises.

Mots-clés :

- interprétation de conférence,

- signes internationaux,

- communauté de pratique,

- compétences

Resumen

Las intérpretes de conferencias de lengua de signos, trabajan tradicionalmente entre la lengua de signos nacional y la lengua oral o escrita del país. Durante su carrera profesional, las intérpretes pueden añadir otras lenguas orales o signadas a su repertorio lingüístico, de esta manera, algunas adquieren los Signos Internacionales (IS) como lengua de trabajo, interpretando así de IS a otras lenguas signadas u orales y viceversa. Los Signos Internacionales varían enormemente según el contexto de uso, ya que los acuerdos con respecto a su utilización son limitados y no existe itinerario formativo preestablecido para su aprendizaje. Habitualmente, para cualquier persona signante, la adquisición en IS se da a través de la interacción con personas signantes de otros territorios con lenguas de signos diferentes a la propia. En este artículo, exploramos el concepto de intérpretes de IS de conferencias como una comunidad de práctica, donde las intérpretes principiantes adquieren y las experimentadas profundizan en competencias interpretativas a través del aprendizaje situado. Este tipo de aprendizaje mediante la práctica, puede llevar al desarrollo de una destreza y un desempeño profesional excelentes en la interpretación de conferencias en IS. Presentamos datos de una encuesta internacional realizada a intérpretes de IS de conferencias en 2019, así como 11 entrevistas en profundidad llevadas a cabo con participantes seleccionadas tras realizar la encuesta para ahondar en la materia. Los resultados de nuestro estudio sugieren que existe una comunidad de práctica de intérpretes de IS de conferencias y que es esencial para las intérpretes participar en la misma para desarrollar las competencias requeridas para el desempeño de la profesión.

Palabras clave:

- interpretación de conferencias,

- signos internacionales,

- comunidad de práctica,

- competencias

Article body

1. Introduction

Conference interpreting between a spoken and a signed language is becoming more common (Turner, Grbić, et al. 2021). In conferences with multilingual signing participants, it is an option to provide interpretation into and from International Sign (IS), instead of, or in addition to, interpretation into and from multiple national sign languages (NSL). We start this article with a brief overview of what IS is and a description of the current landscape of conference interpreters who work with IS. Carried out by a relatively small group, conference interpreting in IS is perceived as a comprehensive set of specialist language and interpreting skills for which no formal training program exists, other than ad hoc courses. We suggest that interpreters therefore participate in a Community of Practice (CoP) to acquire the relevant competences and expertise. We will take a closer look at the concepts of interpreter competence, interpreter expertise and CoP and apply these to the results of our study. In our discussion, we will highlight the key competences of IS conference interpreters and conclude with how these can be best acquired.

2. International Sign (IS)

Signed languages are fully fledged natural languages with their own lexicon and grammar (Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2001). There are at least two hundred known NSLs in the world and, when signers from different countries meet, they typically do not know each other’s signed language (Quinto-Pozos and Adam 2015). This is when IS spontaneously occurs: deaf people communicating using gestures, signs and characteristics of different signed languages (also referred to as cross signing, Zeshan 2015). Being created by the interlocutors and influenced by their languages, the use of IS varies across regions and individuals and is context dependent, more so than the sociolinguistic variation of a NSL (Kusters 2021a).

IS is a unique phenomenon which has no equivalence in spoken languages and is used as a lingua franca in international contexts as a neutral form of communication for signers with different language backgrounds (Kusters 2021a). Comparisons have been made with English as a lingua franca since both draw on a range of available resources and use these to shape their in-group norms (Bierbaumer 2021). However, what makes IS unique is that signers do not need to know a common signed language to communicate with each other and, in contrast to spoken languages, the rich iconicity in signed languages enables faster understanding, making communication across language borders easier. Importantly, even though the label suggests otherwise, IS is not instantly understood by all signers and it takes frequent exposure and interaction to acquire IS.

Experiences with international forms of communication by deaf people have for example already been mentioned by Mottez, Fischer, et al. (1993). However, during the last decade, an increasing body of research into IS has provided further insights into what IS is and how it is being used globally. Kusters (2021b) has investigated different forms of IS, for instance at conferences, and reviewed the different language policies at events with direct communication in IS and events where interpretation services in IS or NSL were provided, such as the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) Congress. She found that, in international events where interpretation services were provided, the participants expected to fully comprehend the content and that the limitations of IS, in comparison to an NSL, became more apparent. Müller de Quadros and Rathmann (2021) go a step further and state that, based on their research findings, IS is now a language and call it International Sign Language (IntSL). They reason it is a language is because of its vitality, the rich linguistic diversity including sociolinguistic variation, its omnipresence and the possibility to learn it as a second language. They also claim that, similar to other languages, IntSL has a variability and stability of lexical items and can be seen as a global language on its own which is used by deaf communities worldwide.

As an example, a more conventionalised form of IS, a language-like and more established form of IS, can be seen at international events where deaf people gather, such as those organised by the WFD (Whynot 2016). Although the WFD advocates for the use of national sign languages to ensure comprehensive communication, their most recent 2019 statutes[1] state that “IS shall be used at all WFD meetings” (Art. 6.1) “and for communication within the WFD general assembly” (Art. 20.3). The WFD has a related policy that, during their general assembly, no interpretation services are allowed, obliging all delegates to use IS (Green 2015). At their congress in 2019, in Paris, the WFD allowed only presentations in IS or in French Sign Language (LSF). Even though not all international presenters felt competent, they had to quickly adapt to signing in IS (personal communication, Rebecca Ladd, WFD interpreter coordinator, 7 August, 2019). The advance of IS as the main conference language is also reflected in the decrease of interpreting services into national sign languages for delegates attending the WFD Congress (Nilsson 2020) and other international events, which is considered problematic as it assumes that all deaf audiences can access conventional, expository, interpreted IS (Kusters 2021a).

3. Becoming an IS conference interpreter

In this article, we focus on interpreting IS at the conference level, a setting in which IS tends to be more conventionalized and is often referred to as expository IS (Whynot 2016). In 2015, the World Association of Sign Language Interpreters (WASLI) and the WFD established the first global accreditation system for IS conference interpreters working for the United Nations (UN). As of 2018, thirty interpreters had achieved accreditation and an additional fourteen interpreters were added in 2022 , one interpreter in 2023 and two interpreters in 2024.[2] In 2022, a new category, “pre-accredited,” was added to the WFD-WASLI accreditation system for those working IS interpreters who are guided by mentors to develop their skills to achieve full accreditation.

There are more interpreters working with IS than are accredited. The exact number of IS conference interpreters globally is unknown, but in our 2019 global study, ninety deaf and hearing IS conference interpreters reported that they work for deaf-led organizations on the private market, or for international organizations such as the UN (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021a). Although the WFD sees the use of IS as a threat to national sign languages, they nevertheless do want to ensure high-quality IS interpretation services at the UN through the accreditation system (WFD 2019). Current and prospective IS conference interpreters see the need for the accreditation of IS conference interpreters; however, they also suggest further improvements of the accreditation process, such as a clear definition of what IS is to understand what specifically is accredited (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023).

Other than a module on conference interpreting in an existing sign language interpreting program, there are no master level training programs for conference sign language interpreters similar to those for spoken language interpreters (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021a). The relatively few conference interpreters that have IS in their language combination have learned IS through interaction with and observation of signers and interpreters and have acquired conference interpreting skills through self-learning. Interpreting IS at conferences is seen as a special set of skills that cannot be easily acquired by any sign language interpreter (Moody 2008; Oyserman 2016). Establishing a training program for IS conference interpreters can be one solution to meet the high demand and current practitioners confirm the need for such a program (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023). However, for a training program to be successful, it is essential to identify the specific conference interpreters’ competences (Liu 2009). In the next section, we will look at what these conference interpreter competences are and how they are relevant to IS conference interpreters.

4. Interpreting competences and expertise

Studies on interpreting IS have so far explored selected interpreter competences, such as strategies (McKee and Napier 2002; Stone and Russell 2014; Sheneman and Collins 2016; Nana Gassa Gonga, Crasborn, et al. 2020), preparation (de Wit and Sluis 2016; de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021b) and professional practices (de Wit 2020; de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021a). All these empirical studies underline the importance of the interpreting team collaboration, especially the need for the interpreters to discuss concepts and cooperation strategies ahead of the assignment. However, no study has yet provided a comprehensive framework of IS conference interpreter competences. We will therefore look at the competences of conference interpreters in general (mostly for spoken languages) and how these can inform the competences of IS conference interpreters.

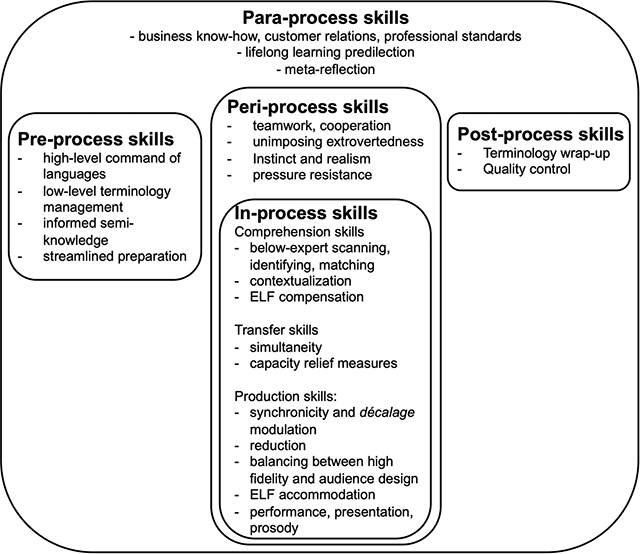

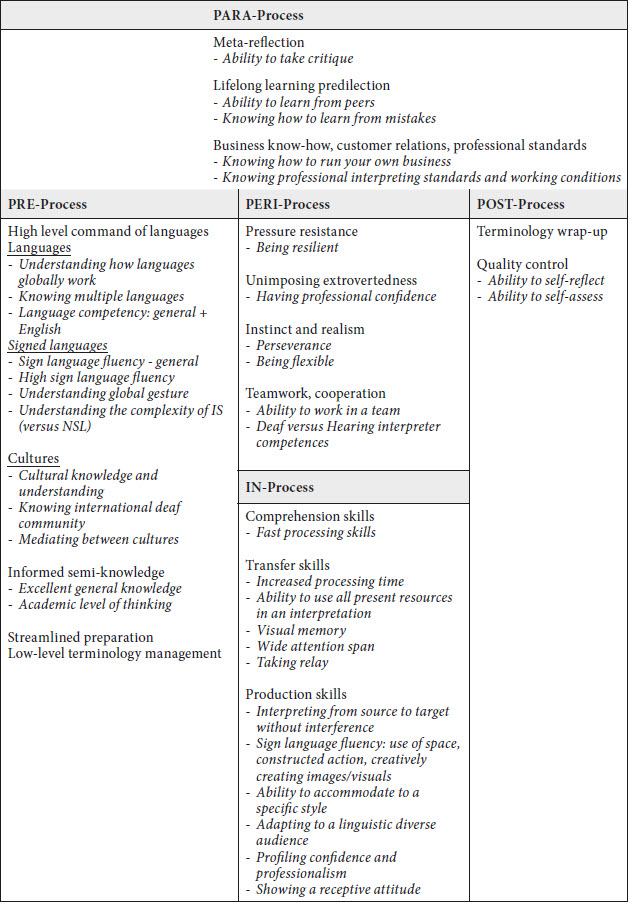

Several handbooks on interpreting list interpreter competences, but empirical research into interpreting competence models is minimal (Tiselius and Hild 2017) and there is no universally accepted model of interpreting competence (Wang, Xu, et al. 2020). In this article, we follow the definition of interpreter competence as summarized by Tiselius and Hild (2017: 426) “a set of different capacities and skills necessary for completing an interpreting task.” In our study, we collect the perspectives of interpreters and therefore take, as a starting point, the process-based and experience-based model of interpreter competence from Albl-Mikasa (2012: 63) (Figure 1), as she describes interpreter competence from the viewpoint of the interpreter. Her model is an adaptation of Kalina’s model (2002) and has five categories: pre-, peri-, in-, post- and para-process skills, the latter having been added to the model to account for the business-related matters which her informants considered a major part of their work. Albl-Mikasa’s model describes the interpreter’s competences within each of the categories, which we refer to in the Results section of this paper when we apply it to our findings.

Figure 1

Process- and experience- based model of interpreter competence (Albl-Mikasa, 2012: 63)

Various studies have shown that an interpreter must possess unique competences that go beyond mere bilingual skills (Angelelli and Baer 2016), and as shown in Figure 1. The foundation of this specialized knowledge and skills can be acquired in an educational program. However, there is no common agreement on how conference interpreters are best trained. The educational programs for conference spoken language interpreting tend to focus on teaching the student cognitive skills and strategies that give the student the tools to automate their interpreting process (Ruiz Rosendo and Diur 2021). Yet upon graduation, these acquired interpreter competences do not necessarily meet the competence level required to work at international organisations (Moser-Mercer 2008; Duflou 2016; Ruiz Rosendo and Diur 2017; Varela Garcia 2021). A blended learning environment is needed for this, conference interpreters acquire their competences via scaffolding: a combination of academic training and learning in practice during training (Motta 2016).

Interpreters must also cultivate their acquired competences post training (Albl-Mikasa 2013) through an interactive process (Kalina 2002) and well-practiced strategies (Liu 2011). This interactive process is fundamental and contributes to expanding and fine-tuning the key competences during their early career. Undertaking deliberate interpreting practices in authentic interpreter situations gives the interpreter the accumulation of interpreting experiences which ultimately leads to expertise (Sunnari and Hild 2010; Albl-Mikasa 2013; Tiselius 2013). The theory of expertise was first proposed by Ericsson and Smith (1991) and further expanded until his latest update in 2018 (Ericsson, Hoffman, et al. 2018). In his work, Ericsson showed that expert performance, instead of it being innate, was predominantly based on domain specific knowledge and the accumulation of expert skills through training and deliberate practice.

Expertise in conference interpreting can be defined differently depending on your perspective as an interpreter, consumer, organizer and so on (Moser-Mercer 2021). In this study we take the perspective of the interpreter and will first share our definition of interpreting expertise to allow better comparison of data and analysis (Tiselius 2013). To measure expertise, there are quantitative and qualitative components, such as years of interpreting experience and user satisfaction (Tiselius and Hild 2017). We suggest a combination of such components as proposed by Delgado Luchner (2015). She defines an expert interpreter as an interpreter who has completed academic training, has delivered five thousand or more interpreting hours post training (Moser-Mercer 2010: 264) and who has the competence to shift their attention between interpreting tasks.

Due to the complexity of IS and interpreting thereof (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021b), what is specifically of interest to IS conference interpreting is the distinction between routine versus adaptive expertise (Tiselius and Hild 2017). Routine expertise is situation specific and rule based. An interpreter with adaptive expertise can monitor their tasks while solving a problem and is flexible to make the necessary changes when the applied strategies do not lead to a good result. For this, the interpreter uses their domain-specific knowledge, a higher degree of flexibility and innovation in problem solving and use of meta-cognition in challenging situations (Moser-Mercer 2008). An interpreter cannot simply change from routine expertise to adaptive expertise with some extra practice. To achieve this level of adaptivity, the interpreter must be exposed to situations that challenge their meta-cognition to solve problems and organize their knowledge. This type of expert performance can however only be objectively measured in controlled laboratory conditions (Ericsson 2000).

IS interpreting appears to be an expert, adaptive, competence which is predominantly acquired through observation and socialization (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023). We suggest that this acquisition takes place in a CoP of interpreters with varying degrees of experience, which we will explore in the next section.

5. Community of Practice

The concept of a CoP is a learning-based theory originally proposed by Lave and Wenger (1991) and further developed throughout the years. We will first discuss their work around CoP and the concept of Situated Learning before taking a closer look at how the theory can be applied to the IS conference interpreting profession.

Lave and Wenger (1991) defined CoP as a group of people or professionals who share a concern or a passion for a topic they undertake together. This shared interest and participation in the group activity allows the individual to learn. The CoP is open to experienced and novice learners and membership in the CoP is considered essential for learning. Not only does the participant gain knowledge and practice, their learning trajectory in the CoP is also essential for building their identity, which is created through the mutual engagement with others. Critical is that their identity not be fixed but be continuously shaped and negotiated by the present context the participants are in, as well as by the histories of the practice and generational politics (Wenger 1998).

The participant’s learning trajectories in a CoP can take place on the periphery or through partial involvement (Wenger 1998). Those on the periphery demonstrate a degree of non-participation which might change to full participation, referred to as legitimate peripheral participation. This is typically the case with newcomers to the CoP who are not fully participating yet in the CoP. It even might happen that they will never fully participate. Participation can also be defined by non-participation, either by choice as a strategy or by a related institution. For example, an individual may not agree with the regime of competences in the CoP and chooses not to participate. A participant can also decide to join another CoP which they consider more relevant to them. These different levels of participation in the community can also be observed in the WFD-WASLI accredited list of IS interpreters, as some are pre-accredited and still on the periphery of that community and considered newcomers.

Learning in practice in a community takes place when there is an interaction between competences and experiences. Such “situated learning” is not the same as an internship during formal education (Lave and Wenger 1991). In situated learning, the learning transpires through the interactions and the actual experience participating in a particular activity (Roberts 2006). The individual can then transfer and apply the learned knowledge to other domains. As suggested by Moody (2008), IS interpreters need years of experience in the field to apply what they have learned over the course of a dedicated interpreter training.

The theory of situated learning through CoP has been applied to diverse groups, as well as specific professions, for example management professionals (Handley, Sturdy, et al. 2006; Roberts 2006) and interpreters (González-Davies and Enríquez-Raído 2016), specifically community sign language interpreters (Dickinson 2010), community spoken language interpreters (D’Hayer 2012) and conference interpreters (Duflou 2016). Duflou (2016), who studied conference interpreters in the European Parliament as a CoP, concluded that part of the interpreter’s required interpreting knowledge and skills are situated competences which can only be obtained in practice. She suggested that interpreters learn within a community of practice, rather than by undertaking deliberate practice to acquire competences. In this conceptual framework, the interpreter learns by becoming a member of the CoP and linking their individual learning process to that of the community as a whole.

Other than ad hoc opportunities, conference sign language interpreters do not have an opportunity to attend any formal training in IS conference interpreting (Turner, Grbić, et al. 2021). Drawing on Duflou, we suggest that membership in a CoP is therefore a prerequisite for IS conference interpreters to obtain the required competences and knowledge of professional practices. To investigate this idea, we asked practitioners to inform us of their practices and perspectives with regards to required competences for interpreting IS at conferences.

6. Positionality

Before we describe our research methodology, we shall first state our positionalities as interpreter researchers (Bendazzoli and Monacelli 2016). We are all trained national sign language interpreters by profession and two of us are accredited by WFD-WASLI as IS interpreters as well as members of the International Association of Conference Interpreters (AIIC). In addition, in 2014, two of us were also involved in developing the first WFD-WASLI accreditation system, including defining IS interpreter’s skills. Our research has an emic approach (Tiselius 2018) and would not have been possible without the support of our national and international signing communities, of which we are also members.

7. Methodology

To identify the competences and knowledge of IS conference interpreters, we collected the perspectives from current practitioners with various levels of IS conference interpreting experience, ranging from less than a year to over forty years. Their real-world experiences working as an IS conference interpreter provide a first overview of the required competences.

As in our previous study on IS conference interpreting (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023), we used the same mixed method (Hale and Napier 2013): a global online survey on the profile of sign language interpreters who work with IS in conference settings (N=90) and interviews with eleven IS conference interpreters on their perspectives on IS conference interpreter competences and its community. All studies took place in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic.

The comprehensive anonymous survey explored the practitioners’ demographics, language profiles, training, employment and professional practices (see, for a detailed description of our survey methodology, de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021a). In the survey we also used Likert scale questions and focused on the competences and characteristics required of IS interpreters as well as the respondents’ perspectives on professional practices in the IS interpreting community. Based on our literature review on IS interpreting, the survey respondents were presented with descriptions of IS conference interpreter competences and characteristics and were asked to rank these on a five-point Likert-type.

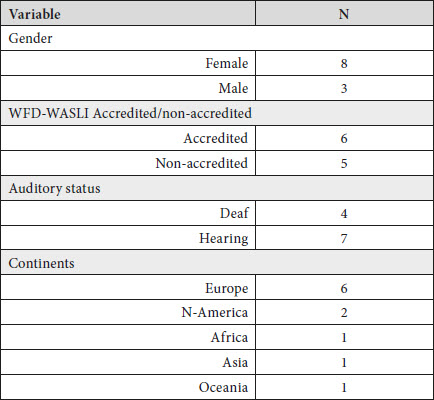

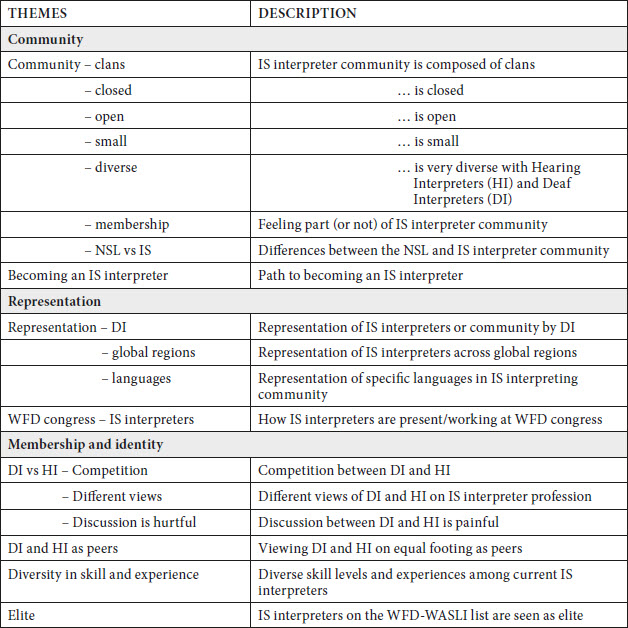

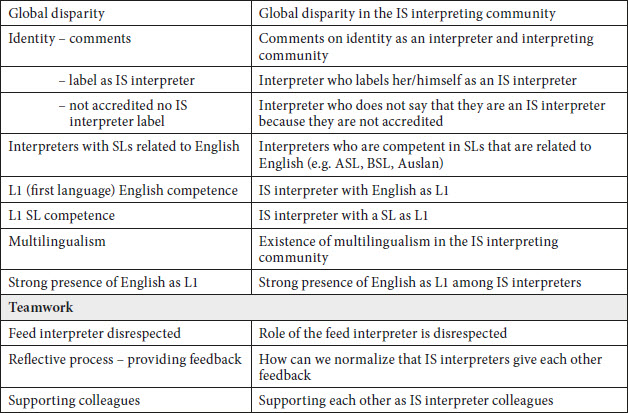

Several survey respondents indicated their willingness to participate in a follow-up interview. We strata sampled the deaf and hearing IS interpreter interviewees by region, accreditation status and gender, representing practitioners’ diversity (see de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023). In the semi-structured interviews, we used questions drawn from salient survey responses focusing on the practitioners’ perspectives on the community, meaning the generally known group of IS interpreters. The interviews were conducted in IS or English according to the interviewee’s preference and video-recorded for analysis. All interviews were annotated in English and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2019) in ELAN[3] (see de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023).

8. Results

We analyzed the survey and interview data on respondents’ perspectives on IS conference interpreter competences, their professional practices and their perspectives on the IS interpreting community. We will first provide the demographics of the respondents and then present the results, starting with the IS conference interpreters’ community, their professional practices, followed by their competences. The interview segments concerning the community and practices are illustrated with respondents’ quotes from the interviews (marked with R). To ensure anonymity within this small group of IS interpreters, the quotes do not disclose demographics or names of the respondents. The quotes from the survey on competences and practices were provided anonymously in the comment sections of the survey answers and are therefore not labeled by respondent (i.e. they are only indented). All the quotes serve as an illustration of the identified themes (listed in full in Appendices 1 and 2).

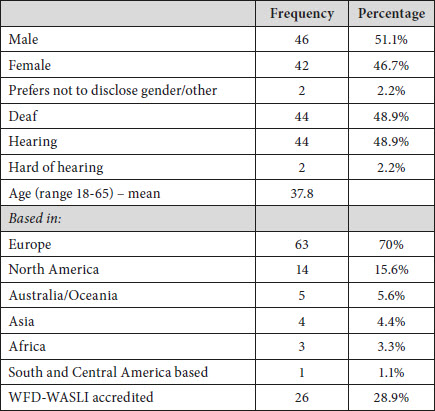

Out of the 108 global survey respondents, a total of ninety sign language interpreters work at conferences with IS (Table 1) and with eleven of those we conducted interviews (Table 2). Of the thirty WFD-WASLI IS accredited interpreters in 2019, a total of twenty-six (87%) participated in the global survey. For further details about the respondents’ work experience and training, we refer to our previous article (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021a).

Table 1

Survey: Demographics of IS conference interpreters (N=90)

Table 2

Interviews: Demographics of IS conference interpreters (N=11)

8.1 Community

The interviewees’ perspectives on IS interpreters, referred to during the interviews as the IS interpreter community, are diverse (Appendix 1). The interviewees describe this community as broader than an IS CoP. Those interpreters that are accredited by the WFD and WASLI as IS interpreter are seen as elite and the core of the community, grouped into different clans. Some feel part of that community and others do not:

R7: I think some accredited interpreters are also turning their backs on others and behave elitist. I have seen it. With both deaf and hearing interpreters.

Some respondents describe the tense relationships between deaf and hearing interpreters. Generally, they would like to see all interpreters be more on an equal footing, which would also bring further opportunity to support each other and normalize providing feedback in deaf and hearing interpreter teams:

R8: All this time, you know, thinking that, you know, we’re all one big happy family, and then to find out that there’s this massive chasm, it’s just uh, and how do you fix it? And I actually don’t see people as deaf or hearing, you know, so I see people as interpreters.

The languages of IS interpreters also influence the representation of IS interpreters globally. Many interviewees call for representation across all global regions rather than predominantly in Europe and North America:

R1: I think with IS it’s more focused on having English, French, and International Sign. Those are the most common languages, or Spanish, that you go into. And we don’t have that kind of balance when you look at global south recognition. So, for example, when you do apply for accreditation it’s in those language combinations and even if you go down the dropdown list for ASL, BSL, you have those, but you don’t have for example Nigerian Sign Language.

Several respondents describe a large global disparity between IS interpreters and suggest that one of its causes is the strong presence of interpreters with English as a native language who are also competent in corresponding signed languages, such as American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL), and Australian Sign Language (Auslan).

R11: Many of the international sign interpreters in Europe have English as a first language and many have more than one sign language, such as ASL, BSL and Auslan, all those sign languages that are related to English. There are only a few international sign interpreters that know other European signed languages. So that is why they also prefer each other to work with as they have the same signed languages. I must add that I appreciate their languages, but it is important that in an interpreter situation the interpreter not only works with the languages they have themselves but that they can also match the languages of those in the setting.

Most importantly, the interviewees describe participation in a CoP as the essential path to become an IS interpreter; however, it is a path that comes with obstacles. The respondents feel that the CoP is open to some and closed to others:

R4: They [The IS interpreters] saw that I was invested, and they were open and welcoming. And now I really feel that they have taken me in.

R8: But there’s there is also gatekeeping by some interpreters, so gatekeeping definitely does happen.

Although the CoP is diverse, there is close cooperation. Sharing knowledge and expertise are an essential function of the community:

R4: So it was good that I did not understand, and I had a hard time understanding. It made me work hard to observe and try to understand […] These endless observations helped me create my understanding. Going to all these places and seeing how the interpreter worked differently, and what worked well, it really helped a lot.

R11: When we are all working as an interpreting team for a conference, we should be open towards our team members. We can then together reach the highest stars. For me it is important not to separate the deaf and hearing interpreters, but we have a common goal to get to.

Even though the respondents do not use the term CoP, overall, all the interviewees agree that a novice IS interpreter can only gain the required competences and knowledge through situated learning with experienced IS conference interpreters who also act as gatekeepers.

8.2 Professional practices

The practices of IS conference interpreters have become more institutionalized in recent years. For instance, the increasing demand for IS interpreting services (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021) has led to the establishment of an accreditation system:

R10: I think what we’re seeing now is a great professionalization of international sign interpreters as opposed to the way I got into it. Which was a deaf person from another country saying oh I can understand you. You know. You come and do this. Which was partly a bit haphazard.

Not all of the ninety IS conference interpreters identify themselves as an IS interpreter. Fifty-two (57.8%) say they are an IS interpreter because they are accredited by WFD-WASLI or have the IS interpreting skills and have interpreted IS for many years. As one respondent says:

IS is the salient part of my language combination because this is what I do and because of my experience and accreditation by WFD-WASLI.

We asked the fifty-two persons who label themselves as an IS interpreter at which level they would rank themselves. Two (3.8%) see themselves as beginner, twenty-two (42.3%) as intermediate and twenty-eight (53.8%) as experienced. The other thirty-eight (42.2%) say they do not want to call themselves IS interpreters because they do not interpret IS frequently, or are not accredited by WFD-WASLI, or do not (yet) have the IS interpreting skills or the opportunity to develop them.

I don’t feel qualified to do that just yet. Right now, I feel like I do the work when no one better qualified can do it and are willing to work with [me] as I muddle through.

Next to language fluency and interpreting competences, interpreters are to show professional conduct in their practices (Albl-Mikasa 2012). Membership in a professional organization informs practitioners and is likely to influence their professional representation. We asked respondents about their membership in organisations. Most respondents are an individual member of their national interpreter and deaf association and many also of international organisations, such as WASLI, EFSLI (European Forum of Sign Language Interpreters) and the WFD. Some are a member of other organisations, such as EUDY (European Union of the Deaf Youth), AIIC (International Association of Conference Interpreters) and regional associations or other national interpreter associations besides their own. The vast majority are members of one or more organisations. Of the twenty-six WFD-WASLI accredited IS interpreters, most, but not all, are a member of the WFD (21; 80.8%) and WASLI (19; 73.1%).

8.3 Competences

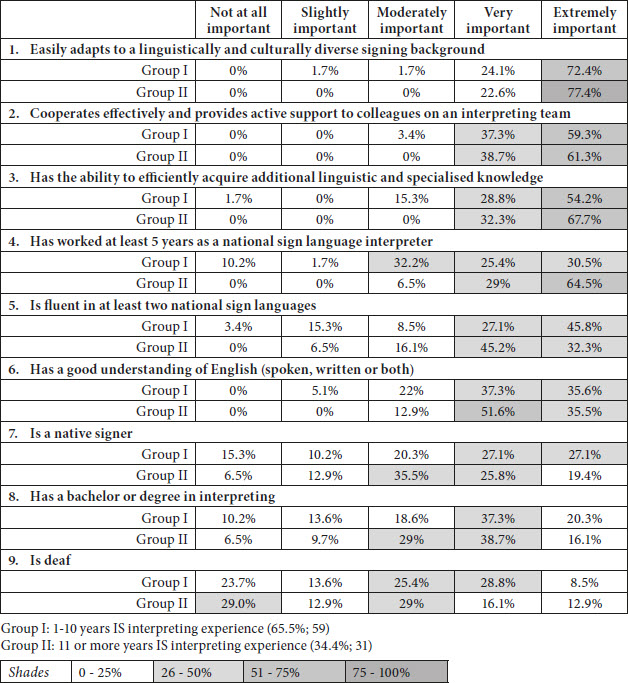

The nine descriptions of IS conference interpreter competences and characteristics (Table 3) were ranked by the respondents on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “not at all important” to “extremely important.”

The experience in interpreting IS at conferences varies among the survey respondents (M = 9.6, SD = 6.3; range 1-30+ years) years. In Table 3, we compare the perspectives of those with an average of less than ten years of IS interpreting experience (n = 59) to those with more than ten years experience (n = 31).

In both groups, the respondents consider the following top three competences as “very important” or “extremely important”:

-

the IS interpreter’s adaptative skills to cultures and languages;

-

the competence to acquire linguistic and specialized knowledge;

-

the ability to collaborate well in a team.

Opinions between the two groups of interpreters start to diverge when it comes to fluency in two national sign languages and the number of years an interpreter should have worked in their NSL before becoming an IS interpreter. Those with less IS interpreting experience consider the number of years of working as a NSL interpreter of lesser importance.

Altogether, the respondents attach the least importance to the following characteristics:

-

being deaf

-

being a native signer

-

having a bachelor’s degree in interpreting.

These three characteristics also have the widest distribution across all levels of importance, within both groups, indicating a greater diversity of opinions compared to the other competences and characteristics.

Table 3

Perspectives on competences and characteristics of IS conference interpreters (N = 90)

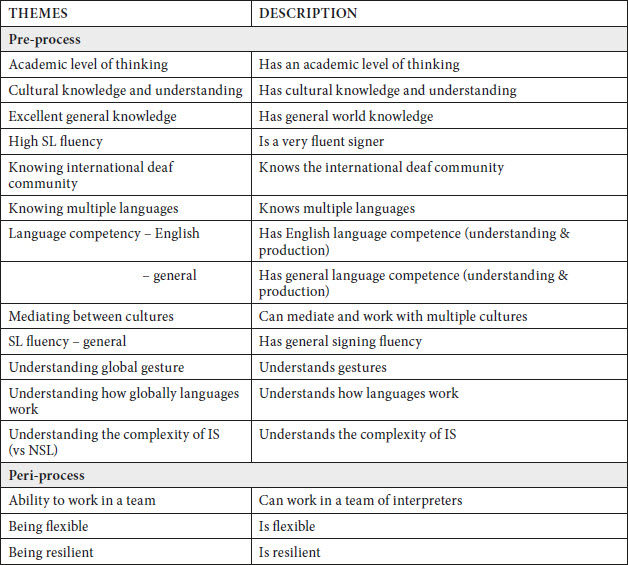

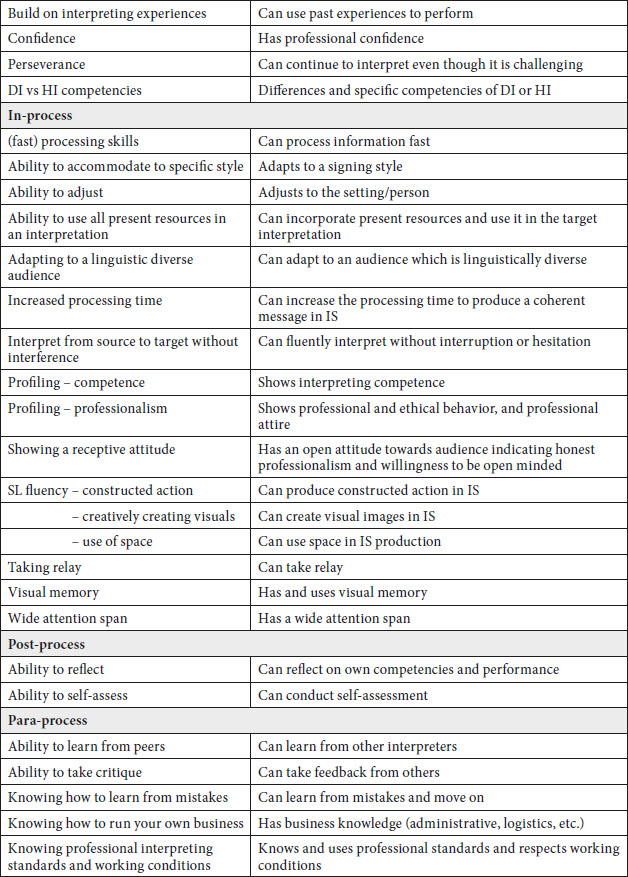

The thematic analysis of the eleven individual interviews provided further details on the IS interpreter competences (Appendix 2). We incorporated these competences into Albl-Mikasa’s (2012) model of interpreter competence (Table 4) by inserting the identified themes in the five categories of the model. The thematic analysis gave us many details on linguistic and cultural competences and we expanded the original model’s pre-process category by adding “cultures” and specified languages and signed languages (underlined in Table 4). The competences related to terminology, a fundamental competence among spoken language interpreters, were not explicitly mentioned by the interviewees as “terminology management” and thus not labeled as a theme by us. Preparation was not explicitly mentioned either, although it was implied in teamwork and expanding knowledge. General interpreting competences were also present in our thematic analysis, such as “ability to self-reflect.” Next, we will discuss several competence clusters that stood out from the thematic analysis, which also illustrate the interviewees’ focus on the specific task of IS conference interpreting.

Table 4

Process and experienced based model of interpreter competence—adapted from Albl-Mikasa

Romanized: Original model

Italics: Inserted themes from the thematic analysis

Underlined: Added categories from the thematic analysis

8.3.1 Linguistic and cultural competences

The respondents emphasize the requirement to know multiple languages and cultures and having a high sign language fluency, as illustrated by the following comment:

I mean I think that’s hard work and I think people have to understand that international sign is not just about changing your sign language but it’s about understanding the people and the culture.

English is also highly recommended as it is the lingua franca for many international organizations and for the WFD and WASLI, but at the same time some respondents warn of the dominant influence of English on IS:

The knowledge of English as an international language is very useful, but too many monolingual English speakers do not have the linguistic flexibility of bilingualism or multilingualism in the same modality, which I believe is important to have.

And since IS is a collaborative language, it is often useful to have people involved in the language negotiation process who are not using English as a framework.

In general, the respondents see it as a key prerequisite that IS interpreters have the competence to understand the complexity of IS versus a national sign language and to be able to navigate between diverse deaf and national cultures.

8.3.2 Knowledge

Essential is also being an expert in mastering specialized knowledge and processing it fast and at a high level. To be able to do this, one respondent comments that interpreters need:

The capacity to use strong visual space is the most important. You must be able to get it fast, integrate it and produce it fast. Not needing the time to think. But take the source, create something and if you are able to do that, then the whole process will go smoothly.

Thus, IS interpreters must have strong cognitive, visual and physical skills to produce a highly visual comprehensible interpretation for a broad international deaf audience.

8.3.3 Teamwork

The core of IS interpreting is being able to cooperate in a team of interpreters, according to the respondents. They emphasize that individual interpreters bring different skills, competences and experiences to the team which are essential to co-create the best possible IS interpretation. As one respondent explains:

If I am co-working, I must discuss with my co-worker beforehand how we are working together. For example, who goes first. It is not about your ego it is a team effort. It is not about me, but it is about “we.” Or more, like three or four people in the team. And you must support each other, and not push each other down, but be supportive and reassure your co-workers.

Accordingly, individual interpreters should be flexible, not only towards colleagues, but also in adapting to a diverse audience and audiences. Resilience and perseverance are two essential traits that stand out from the interviews, as seen in the comment:

I think you must be resilient to interpret in front of a large or small audience. And able to receive feedback from the audience. And that I am confident that I know I can do the job right.

This is because IS interpreting is associated with high and diverse demands that are often not easy to meet.

8.3.4 Reflection and learning

The respondents emphasize the relevance of a high-quality professional interpreter training program, as this would give the interpreter the theoretical foundation to reflect on and discuss interpreting. However, they state that such training does not necessarily have to be at bachelor’s level or via a traditional pathway, especially considering that deaf interpreters currently do not have the same possibility as hearing interpreters to access an interpreter training.

People will feel more confident and more secure if they’ve had some kind of theoretical input or some kind of formal learning. But that doesn’t take away from the need to be able to interact with people in a variety of settings and from a variety of places with a variety of sign languages.

In addition, they suggest that having a mentor for IS interpreting is critical. Because IS changes depending on the contexts and the interlocutors, interpreters are required to continuously update their skills and learn through self-reflection and observation in real live events.

8.3.5 Native signers and deaf and hearing interpreters

Another important theme that stands out is the community members’ skills of deaf versus hearing IS interpreters. The interviewees acknowledge the diversity of skills and experience, but also describe a strong competition among professionals. Some respondents experience the discussion between deaf and hearing IS interpreters as hurtful and as a sensitive political issue and are hesitant to give comments. They do highlight that the lived experience as a deaf person using IS and signed languages, as well as being a native or heritage signer, whether hearing or deaf, can bring specific skills:

Having a deaf view or a strongly visual-kinesthetic view enables creative skills about how to convey meaning in IS.

Furthermore, the respondents find that some skills are more important than the interpreter’s audiological status or being a “native” signer:

I think the technical skill of interpreting is more pronounced in IS so that it is a more important value than whether someone is native or is deaf. […] When it comes to working in a team, I want skilled professionals by my side and doing a good job because they are skilled interpreters, not because they are deaf or hearing.

Overall, respondents emphasize the relevance of the linguistic and cultural competences as a requirement for IS conference interpreters, but do not list being deaf as sole requirement.

9. Discussion and conclusion

In our study, we confirm the presence of a CoP of IS conference interpreters. IS interpreters learn by observing and collaborating with peers (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2021a). Novice and experienced IS conference interpreters can cultivate their learning through deliberate practice (Ericsson 2000). Respondents state in practice that self-learning is critical, the IS interpreter must: be able to self-assess, reflect, take critique and learn from others. When they are encouraged by IS interpreters and deaf communities to interpret IS, they can become part of the IS interpreting CoP. Engagement with the members of the CoP gives them access to knowledge and practice (Roberts 2006).

In this CoP, novice IS interpreters can acquire the skill set needed for interpreting IS at conference level and experienced interpreters can cultivate their own skills. As there is no formal training program for IS conference interpreters, participation in this CoP provides the main opportunity to acquire the needed competences and practitioners therefore consider it a requirement.

The responses show that the CoP of IS interpreters is not homogeneous and has different degrees of interpreters’ involvement as not each member aspires to full participation (Handley, Sturdy, et al. 2006). Not everyone who is interested in becoming an IS conference interpreter is automatically given access to the CoP. Those who want to participate in the CoP say they first must show dedicated interest and involvement with the international signing community. The membership to this CoP is informally controlled by members, practitioners themselves, as well as through the accreditation by WFD-WASLI. The CoP members are considered by some practitioners as gatekeepers as they are the ones responsible for guiding novice interpreters through their acquisition process. The accreditation status given by WFD-WASLI to individual interpreters defines who is fully participating in the CoP, accredited, and who is on the periphery, pre-accredited or not accredited at all. Being accredited gives the interpreter the external validation to call themselves an IS interpreter. The interpreter’s participation in the CoP can, next to creating a sense of belonging, also influence the development of their identity (Bierbaumer 2021). Even though most respondents see themselves as an intermediate or experienced IS interpreter, only a slight majority publicly states they are an IS interpreter.

Learning in practice is an essential part of building up the needed competences (González-Davies and Enríquez-Raído 2016) and must be supplemented with extensive experience to acquire the needed skills (Varela Garcia 2021). Next to situated learning, IS conference interpreters suggest formal training for IS conference interpreters, deaf and hearing, where also an academic foundation in IS conference interpreting skills can be acquired.

This study presented a first model of IS conference interpreter competences which can be used for training future practitioners. We followed Albl-Mikasa’s (2012) process and experienced based model of spoken language interpreter competence and adapted it with the competences stated by IS conference interpreters. The interpreting competences for IS conference interpreters differ from those for spoken languages and NSLs. Practitioners state that these differences are due to the unique flexibility of IS and its users, requiring interpreters to be competent in continuously adapting linguistically and culturally.

The respondents emphasize that the IS conference interpreter must display professional confidence and a receptive attitude. For example, when audience members indicate they do not understand the IS interpretation, the IS conference interpreter needs to quickly adapt the IS in a non-disruptive manner. This adaptive expertise is a competence that develops over time in authentic interpreting settings, where the interpreter’s meta-cognitive skills are challenged. The interpreter cannot use ready-made solutions but must strategize their knowledge to solve any issues (Moser-Mercer 2008).

Cooperation skills are also essential within the IS interpreting team. IS interpreters say they rely heavily on their team members to co-construct the most comprehensible interpretation. They do this by bringing together their individual knowledge, experiences and skills to create a broader pool of competences that they can source from.

Unlike NSLs and spoken languages, IS is not conventionalized and can vary greatly depending on the context, requiring interpreters to acquire IS interpreting competences in practice. To learn these adaptative linguistic and cultural cross-signing skills, the interpreter needs to interact in authentic settings with other signers, for example, by actively engaging with signers from across the world in international deaf events. This will give them insight into the complexity of IS, which is different from learning a national sign language in a formal educational program. Practitioners underline the importance of an IS interpreter’s fluency in multiple languages, but find it less relevant whether the interpreter is a native signer or deaf. Above all, they state that IS interpreting requires a lot of perseverance and resilience as well as the willingness to keep learning.

In summary, the situational nature of IS necessitates IS conference interpreters to possess expert skills in interpreting. The findings of our study indicate that these key competences can currently only be acquired and cultivated alongside experienced interpreters in a CoP. Considering the demand for a formal training by current IS conference interpreters (de Wit, Crasborn, et al. 2023), efforts should be made to explore the possibility of establishing a training program to provide the theoretical foundation for IS conference interpreting in combination with situated learning opportunities in a CoP.

The world is globalizing and so are signing communities. The Covid-19 pandemic has influenced the dissemination of expository IS. For example, the WFD organized an increasing number of webinars in IS and more international events are being made accessible via remote IS interpretation services.[4] These effects are not accounted for in this study, which was conducted in 2019 before the pandemic. However, as more public events are hosted remotely, it is reasonable to assume that the visibility of IS interpreters has increased. This increase is likely providing more online learning opportunities for all novice and experienced IS interpreters around the world, especially for those who find it difficult to gain access to the CoP in a more traditional manner. It would be of interest for future studies to see how this change has affected the CoP of IS conference interpreters and the acquisition of IS interpreter competences. We might see a catalyst effect on the conventionalization of expository IS and, as remote work has no geographical borders, more opportunities for IS interpreters located outside of Europe and North America. This would also give more opportunity for new interpreter team combinations and online situated learning in a larger CoP.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1. Themes on IS interpreting community

Appendix 2. Themes on competences

Acknowledgements

This study was partly made possibly by VICI grant no. 277-70-014 from the Dutch Research Council.

Notes

-

[1]

World Federation of the Deaf Statutes. World Federation of the Deaf. Consulted on 25 June, 2024, <https://wfdeafnew.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/WFD-Statutes-26-July-2019-FINAL.pdf>.

-

[2]

IS Accredited Interpreters. World Association of Sign Language Interpreters. Consulted on 2. June, 2024, <https://wasli.org/is-accredited-interpreters>.

-

[3]

ELAN (version 6.0) (2020): The Language Archive. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. Consulted on June 25, 2024, <https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan>

-

[4]

See for example the events on the WFD’s Facebook page. Consulted on June 22, 2024. < https://www.facebook.com/Wfdeaf.org/events>.

Bibliography

- Albl-Mikasa, Michaela (2012): The importance of being not too earnest: a process- and experience-based model of interpreter competence. In: Barbara Ahrens, Michaela Albl-Mikasa and Claudia Sasse, eds. Dolmetschqualität in Praxis, Lehre und Forschung. Festschrift für Sylvia Kalina. Tübingen: Narr, 59-92.

- Albl-Mikasa, Michaela (2013): Developing and Cultivating Expert Interpreter Competence. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. (18):17-34.

- Angelelli, Claudia V. and Baer, Brian James, eds. (2016): Researching Translating and Interpreting. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bendazzoli, Claudio and Monacelli, Claudia, eds. (2016): Addressing Methodological Challenges in Interpreting Studies Research. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bierbaumer, Lisa (2021): A comparison of spoken and signed lingua franca communication: the case of English as a lingua franca (ELF) and International Sign (IS). Journal of English as a Lingua Franca. 10(2):183-208.

- Braun, Virginia and Clarke, Victoria (2019): Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 11(4):589-597.

- D’Hayer, Danielle (2012): Public Service Interpreting and Translation: Moving Towards a (Virtual) Community of Practice. Meta. 57(1):235-247.

- Delgado Luchner, Carmen (2015): Setting up a Master’s programme in conference interpreting at the University of Nairobi: an interdisciplinary case study of a development project involving universities and international organisations. Doctoral thesis. Geneva: Université de Genève.

- Dickinson, Jules Carole (2010): Interpreting in a Community of Practice a Sociolinguistic Study of the Signed Language Interpreter’s Role in Workplace Discourse. Doctoral thesis. Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt University.

- Duflou, Veerle (2016): Be(com)ing a Conference Interpreter: An ethnography of EU interpreters as a professional community. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Ericsson, K. Anders (2000): Expertise in interpreting: An expert-performance perspective. Interpreting. 5(2):187-220.

- Ericsson, K. Anders, Hoffman, Robert R., Kozbelt, Aaron and Williams, A. Mark, eds. (2018): The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ericsson, K. Anders and Smith, Jacqui, eds. (1991): Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- González-Davies, Maria and Enríquez-Raído, Vanessa (2016): Situated learning in translator and interpreter training: bridging research and good practice. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 10(1):1-11.

- Green, E. Mara (2015): One language or maybe two, direct communication, understanding, and informal interpreting in international deaf encounters. In: Michele Friedner and Annelies Kusters, eds. It’s a Small World: International Deaf Spaces and Encounters. Washington D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 70-82.

- Hale, Sandra and Napier, Jemina (2013): Research Methods in Interpreting. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Handley, Karen, Sturdy, Andrew, Fincham, Robin and Clark, Timothy (2006): Within and Beyond Communities of Practice: Making Sense of Learning Through Participation, Identity and Practice. Journal of Management Studies. 43(3):641-653.

- Kalina, Sylvia (2002): Quality in interpreting and its prerequisites A framework for a comprehensive view. In: Giuliana Garzone and Maurizio Viezzi, eds. Interpreting in the 21st Century: Challenges and opportunities. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 121-130.

- Kusters, Annelies (2021a): A global deaf lingua franca? Considering International Sign and American Sign Language. Sign Language Studies. 21(4):391-426.

- Kusters, Annelies (2021b): International Sign as a Conference Language. (Deaf Academics Conference online, Montreal, June 2021). Mobile Deaf. Consulted on 22 June, 2024, https://mobiledeaf.org.uk/presentations/isconferencelanguage/.

- Lave, Jean and Wenger, Etienne (1991): Situated Learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Liu, Minhua (2009): How do experts interpret? Implications from research in Interpreting Studies and cognitive science. In: Gyde Hansen, Andrew Chesterman and Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast, eds. Benjamins Translation Library. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 159-177.

- Liu, Minhua (2011): Methodology in interpreting studies. A methodological review of evidence-based research. In: Brenda Nicodemus and Laurie Swabey, eds. Advances in Interpreting Research. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 85-120.

- McKee, Rachel Locker and Napier, Jemina (2002): Interpreting into international sign pidgin: an analysis. Sign Language & Linguistics. 5(1):27-54.

- Moody, Bill (2008): The role of international sign interpreting in today’s world. In: Cynthia Roy, ed. Diversity and community in the worldwide sign language interpreting profession. Coleford, Gloucestershire: Douglas McLean Publishing, 19-33.

- Moser-Mercer, Barbara (2008): Skill Acquisition in Interpreting: A Human Performance Perspective. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 2(1):1-28.

- Moser-Mercer, Barbara (2010): The search for neuro-physiological correlates of expertise in interpreting. In: Gregory Shreve and Erik Angelone, eds. American Translators Association Scholarly Monograph Series. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 263-287.

- Moser-Mercer, Barbara (2021): Conference interpreting and expertise. In: Michaela Albl-Mikasa and Elisabet Tiselius, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Conference Interpreting. London: Routledge, 386-400.

- Motta, Manuela (2016): A blended learning environment based on the principles of deliberate practice for the acquisition of interpreting skills. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 10(1):133-149.

- Mottez, Bernard, Fischer, Renate and Lane, Harlan (1993): The deaf mute banquets and the birth of the Deaf movement. Looking back: A reader on the history of Deaf communities and their sign languages. Hamburg: Signum Press, 143-155.

- Müller de Quadros, Ronice and Rathmann, Christian (2021): International Sign Language: Two perspectives. Lingua de Sinais Internacional. Consulted on 22 June, 2024, https://youtu.be/wcXrG39zUfo.

- Nana Gassa Gonga, Aurélia, Crasborn, Onno, Börstell, Calle and Ormel, Ellen (2020): Comparing IS and NGT interpreting processing time. A case study. In: Campbell McDermid, Suzanne Ehrlich and Ashley Gentry, eds. WASLI 2019 Conference Proceedings. (Honoring the Past, Treasuring the Present, Shaping the Future, Paris, July 15-19, 2019) Geneva: WASLI, 74-95.

- Nilsson, Anna-Lena (2020): From Gestuno Interpreting to International Sign Interpreting: Improved Accessibility? Journal of Interpretation. 28(2):1-10.

- Oyserman, Joni (2016): Complexity of IS for inexperienced interpreters, insights from a deaf IS instructor. In: Rachel Rosenstock and Jemina Napier, eds. International Sign: Linguistic, usage and status issues. Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press, 192-210.

- Quinto-Pozos, David and Adam, Robert (2015): Sign languages in contact. In: Adam C. Schembri and Ceil Lucas, eds. Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 29-60.

- Roberts, Joanne E. (2006): Limits to Communities of Practice. Journal of Management Studies. 43(3):623-639.

- Ruiz Rosendo, Lucía and Diur, Marie (2017): Employability in the United Nations: an empirical analysis of interpreter training and the LCE. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 11(2-3):223-237.

- Ruiz Rosendo, Lucía and Diur, Marie (2021): Conference interpreting skills: Looking back and looking forward. In: Killian Seeber, ed. 100 Years of Conference Interpreting. A Legacy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 110-121.

- Sandler, Wendy and Lillo-Martin, Diane (2001): Natural Sign Languages. In: Mark Aronoff and Janie Ress-Miller, eds. The Handbook of Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 533-562.

- Sheneman, Naomi and Collins, Pamela F. (2016): The Complexity of interpreting international conferences, a case study. In: Rachel Rosenstock and Jemina Napier, eds. International Sign. Linguistic, Usage, and Status Issues. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 167-191.

- Stone, Christopher and Russell, Debra (2014): Conference interpreting and interpreting teams. In: Robert Adam, Christopher Stone, Steven D. Collins and Melanie Metzger, eds. Deaf interpreters at work: International insights. Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press, 140-156.

- Sunnari, Marianna and Hild, Adelina (2010): A multi-factorial approach to the development and analysis of professional expertise in SI. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 15:33-49.

- Tiselius, Elisabet (2013): Experience and Expertise in Conference Interpreting: An Investigation of Swedish Conference Interpreters. Doctoral thesis. Bergen: University of Bergen.

- Tiselius, Elisabet (2018): The (un-) ethical interpreting researcher: ethics, voice and discretionary power in interpreting research. Perspectives. 27(5):747-760.

- Tiselius, Elisabet and Hild, Adelina (2017): Expertise and Competence in Translation and Interpreting. In: John W. Schwieter and Aline Ferreira, eds. The Handbook of Translation and Cognition. Hoboken: Wiley, 423-444.

- Turner, Graham H., Grbić, Nadja, Stone, Christopher, et al. (2021): Sign language conference interpreting. In: Michaela Albl-Mikasa and Elisabet Tiselius, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Conference Interpreting. London and New York: Routledge, 531-545.

- Varela Garcia, Monica (2021): Is In-House Training the Answer? In: Kilian G. Seeber, ed. 100 Years of Conference Interpreting. A Legacy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 232-236.

- Wang, Weiwei, Xu, Yi, Wang, Binhua and Mu, Lei (2020): Developing Interpreting Competence Scales in China. Frontiers in Psychology. 11:481.

- Wenger, Etienne (1998): Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- WFD (2019): WFD-WASLI Frequently Asked Questions about International Sign. WFD. Consulted on 22 June, 2024, https://wfdeaf.org/news/resources/faq-international-sign/.

- Whynot, Lori (2016): Telling, showing, and representing: conventions of the lexicon in international sign expository text. In: Rachel Rosenstock and Jemina Napier, eds. International Sign: Linguistics, Usage, and Status. Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press, 35-64.

- Wit, Maya de (2020): A Comprehensive Guide to Sign Language Interpreting in Europe, 2020 edition. Baarn: Self-published.

- Wit, Maya de and Sluis, Irma (2016): International Sign. An exploration into interpreter preparation. In: Rachel Rosenstock and Jemina Napier, eds. International Sign: Linguistics, Usage, and Status. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 105-135.

- Wit, Maya de, Crasborn, Onno, Napier, Jemina (2021a): Interpreting international sign: mapping the interpreter’s profile. The Interpreter & Translator Trainer. 15(2):205-224.

- Wit, Maya de, Crasborn, Onno, Napier, Jemina (2021b): Preparation strategies for sign language conference interpreting: comparing international sign with a national sign language. In: Killian Seeber, ed. 100 Years of Conference Interpreting: A legacy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 41-72.

- Wit, Maya de, Crasborn, Onno, Napier, Jemina (2023): Quality assurance in international sign conference interpreting at international organisations. The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research. 15(1):74-97.

- Zeshan, Ulrike (2015): “Making meaning”: Communication between sign language users without a shared language. Cognitive Linguistics. 26(2):211-260.

List of figures

Figure 1

Process- and experience- based model of interpreter competence (Albl-Mikasa, 2012: 63)

List of tables

Table 1

Survey: Demographics of IS conference interpreters (N=90)

Table 2

Interviews: Demographics of IS conference interpreters (N=11)

Table 3

Perspectives on competences and characteristics of IS conference interpreters (N = 90)

Table 4

Process and experienced based model of interpreter competence—adapted from Albl-Mikasa