Abstracts

Abstract

Audio Description is typically used to describe the visual aspects of various cultural products in the creative industries: performed plays, films, sports matches, art gallery and museum items. Such descriptions offer alternative sensory input for blind or partially sighted audiences and have been the staple of research in Audiovisual Translation Studies. There are, however, rather few studies focusing on museum environments and none that examine the niche area of comic art. This article addresses such a gap in two ways. First, it explores comics from an audiovisual translation/accessibility perspective. Second, it reports findings from a pilot study of accessible comic art where the views of selected professionals (curator, comic artists, audio describer) were collected, descriptions for three comics were commissioned and the responses of blind visitors to a comic art museum were gauged. The audio described comics—not without their limitations, as will be shown—are the result of a contingent collaboration of actors in the space of the museum.

Keywords:

- accessibility,

- audiovisual translation,

- comics,

- disability,

- museum space

Résumé

L’audiodescription sert typiquement à décrire les aspects visuels de divers produits culturels dans les industries créatives : les pièces de théâtre, les films, les événements sportifs, les objets dans les galeries d’art et les musées. Ces descriptions offrent des données sensorielles alternatives à un public aveugle ou malvoyant et sont la base de la recherche en traduction audiovisuelle. Il existe cependant bien peu d’études portant sur les musées et aucune n’examine le domaine niche de l’art de la bande dessinée. Le présent article répond à cette lacune de deux façons. D’abord, il explore la bande dessinée du point de vue de la traduction audiovisuelle et de l’accessibilité. Ensuite, il présente les conclusions d’une étude pilote sur l’art de la BD accessible pour laquelle on a recueilli les points de vue de professionnels sélectionnés (conservateur, artistes BD, audiodescripteur), commandé les descriptions de trois bandes dessinées et évalué les réactions de visiteurs aveugles d’un musée de la BD. Les bandes dessinées audiodécrites – non sans limites, dont il est fait mention – sont le résultat d’une collaboration d’acteurs dans l’enceinte du musée.

Mots-clés :

- accessibilité,

- traduction audiovisuelle,

- bandes dessinées,

- handicap,

- espace muséal

Resumen

La audiodescripción sirve típicamente para describir los aspectos visuales de productos culturales en las industrias creativas: obras de teatro, películas, eventos deportivos, objetos de galerías y de museos. Esas descripciones ofrecen una contribución sensorial alternativa a un público ciego o con deficiencia visual y han sido la base de investigaciones en traducción audiovisual. Sin embargo, existen muy pocos estudios sobre los museos y ninguno que examine el campo especializado del arte del cómic. Este artículo aborda la laguna de dos maneras. En primer lugar, explora los cómics desde la perspectiva de la traducción audiovisual y la accesibilidad. En segundo lugar, presenta las conclusiones de un estudio piloto sobre el cómic accesible por el que se recogieron las opiniones de varios profesionales (curador, artistas de cómic, audiodescriptor), se encargaron las descripciones de tres cómics, y se midió la respuesta de visitantes ciegos a un museo de arte del cómic. Los cómics audiodescritos—con las limitaciones que se exponen—son el resultado de una colaboración de diferentes actores dentro del espacio del museo.

Palabras clave:

- accesibilidad,

- traducción audiovisual,

- cómics,

- discapacidad,

- espacio del museo

Article body

1. Introduction

Audio Description (AD) is a verbal commentary offering those who may have lost some degree of vision, or were born with no visual experience whatsoever, what sighted viewers habitually and automatically absorb through sight (Kleege 2018: 100). This commentary helps convey the detail of information, the logical/narrative sequence and aesthetic artifice of a text or cultural artifact. AD can thus play a cardinal role in education, healthcare settings, business environments and in the creative industries. With a gradual change of legal frameworks over the last few decades (Fryer 2016: 19; Kleege 2018: 97), the volume of AD has increased. Just as practitioners, businesses and institutional bodies have been discussing the challenges and opportunities that have arisen, so too, and in parallel to developments in AD practice, the academic community has tried to shed light on the communication specificities and changing professional or technological contexts of AD (Taylor and Perego 2022). Experiencing a veritable boom, AD research has focused on various angles, ranging from audience engagement (Fryer and Freeman 2013; Fryer 2016) to creative uses of language that may optimise user experience (Holland 2009; Walczak and Fryer 2017; Mazur 2022).

Conspicuous with their scarcity are studies on museum contexts. Where available, these studies focus on collected electronic corpora of AD art gallery texts (Jiménez Hurtado and Soler Gallego 2015) in order to prise open specific lexical patterns (categories of verbs, nouns, adverbs), or on the element of subjectivity in language (Soler and Luque 2018), or on audience perceptions, engagement and recall among both BPS (blind and partially sighted) and sighted audiences who may use AD as assistive text for different reasons in each case (Hutchinson and Eardley 2019).

Unlike the studies above, which focus exclusively on the finished products of mainstream museum/gallery items, such as sculpture pieces or paintings, this study will investigate a niche area, where, to my knowledge, there has been no AD before: comic art; “comic art,” which I will use interchangeably with the generic “comics,” refers to a medium of expression (see mediality in Section 3) with increased narrativity (even though other communicative functions are also possible) and historically derived/recognised constraints, such as image(-language) interactions, linear and tabular presentation (and reading of said interactions) and a style of graphic representation unique to the creative team behind it. As the study is exploratory, it focuses on the process of crafting accessible comics with a museum display brief in mind; this constitutes a first step towards what is also known as “interpretation” or “translating meaning” in Museum Studies, that is aligning audience needs (levels of emotional comfort, educational simplicity, inclusion), means of delivering content (media) and an available pool of practitioners (Jimson 2015: 535, 541). This pilot study is the result of a small-scale project that took place at The Cartoon Museum in London in summer 2022 and sought to address the challenges of describing comics. This was done by organising a focused discussion (among a group of comic artists, the curator and an audio describer) at the museum, by commissioning the audio description for selected excerpts from the work of three creators with markedly different approaches to art and, finally, by collecting feedback from blind visitors at the museum (ethics clearance for research with human participants ref. FHMS21-22FASS015EGA). In what follows, I will present a framework for understanding this new niche of AD practice. I will also plot the phases of the pilot in order to answer the question of how accessible comics description may be prepared and what its impact may be. I will finally conclude by exploring future directions.

2. A Heuristic Map of accessible comics media

Responding to the project’s advertisement for participants, a BPS social media user enthused: “[emoji] fuck yeah! I miss comics/Graphic novels so much! It would be great if there were audible versions which this could well lead onto [emoji]” (my emphasis). The frisson of personal interest aside, this response throws up the question of types of access.

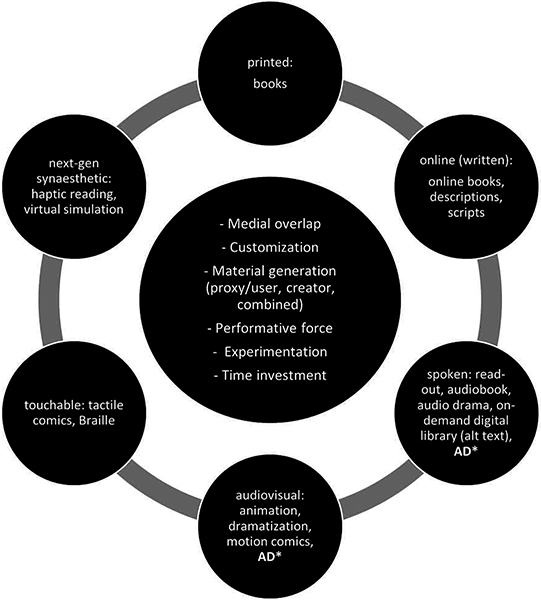

There are various possibilities. Examples may be found in Comics Studies journals (keywords: accessible comics, visual impairment, tactile), in streaming or video-sharing platforms (keywords: motion comics, audible comics, accessible comics, comics description) and on the website of cartoonist and art critic Nick Sousanis, who lists examples from diversity/inclusion journals, grey literature, news items, academic articles and articles written by accessibility charities.[1] Searchable and listed examples are rather disparate and a quick overview reveals a certain bias towards digital, text-to-speech forms. To find unity in this diversity, affinities and interactions must be identified. A conceptual map helped me distil these (see new AVT practices and types of linguistic transfer through conceptual maps; Díaz Cintas 2018; Van Doorslaer 2007 respectively). A first organising principle I used in the outer ring of schematic presentation (Figure 1) was that of medium or channel through which messages reach us and which typically involves a type of technology (Pérez González 2014: 187), from printing to simulations. The typology is fluid, subject to further technological changes, possible pathways of use in specific settings and the human agents involved (see AD crafting in section 3).

A second set of organising principles was subsequently envisaged. This was a combination of (shared) semiotic, technological and social characteristics of accessible media (inner circle), loosely corresponding to basic areas of “interpretation” (audience, media, actions). First, media may overlap, say, when a printed or online book is read out loud. The level of customisation, and thus user autonomy, may vary as does creative input: material may be generated by a single artist, it may be crowd-sourced or remediated (Pérez González 2014: 235) from existing commercial material by proxy users showing allyship to the interests of BPS communities, or it may be the result of co-creation with BPS users, often with the involvement of librarians and information technologists. Performative force (Aaltonen 2013) may range from monotone, text-to-speech machine output, to human acting. Depending on the level of technological experimentation, some media may be eclectic, others broadly available. Finally, the interaction of all of the above characteristics (plus degrees of professionalisation) may render cycles of production lengthy or short.

Figure 1

Accessible comic art

Printed books are an option. Blindness, partial sight and low vision create a very diverse group of readers (Kleege 2018: 2). Some of them had or still have the ability to form a visual or broadly synaesthetic memory of comic books as artefacts.

Online formats can include online books, which may be read with screen readers (see Spoken category) and AI-guided zoom-in. Some web comics also come with transcriptions and/or accessible descriptions from the creative team, such as Hicks and Nichols’s Woven (2018); stand-alone descriptions of existing works can be prepared by other creative industry fans, such as Kerr’s Watchmen (2015) description. In both cases, descriptions proceed panel by panel, offering details on the background, general mood, characters, body language and the visual presentation of the book. A related resource is comic book scripts, which can be bought online from publishers, or found in libraries and in dedicated databases, such as the comics script archive.[2] Scripts normally contain the author’s plain instructions (basic-plot style) or detailed, definitive instructions (full-script style) to the illustrator; these may include “the setting, angles, characters’ emotions, as well as the words of each character [and relative] position of characters,” instructions which are either carried out or extensively discussed/reworked when illustrations come to life (Asimakoulas 2019: 34). BPS readers use scripts as entry points, to discover comic art, to glean rich contextual information and to understand formal aspects (Shifrin 2016). A script, for instance, can explain colour, degree of stylisation or the way three-dimensionality and scale are suggested in two dimensions. Yet there are drawbacks, such as the varied quality, completeness (final drafts) and erratic availability of scripts.[3]

As mentioned above, books may be read by a sighted viewer. This can be someone close to a BPS individual who simply uses their voice, or a more tech-savvy online community tuned into accessibility issues. For instance, a tutorial by Assistive Technology Blog offers tips on creating accessible scene descriptions, acting out a text, and combining these tracks with freely downloadable sound effects, using Audacity, an open-source sound editing application.[4] Greater reader autonomy in genre selection and reading pace can be expected in audiobooks, some of which score high on the performability scale and therefore have long production cycles. There are characteristic examples: Amazon’s Sandman (2022), adapted from DC’s dark fantasy comic (1989-1996), an 11-hour audio, narrated by 8 well-known artists plus the creator, Neil Gaiman; or the four audiobook volumes of The Boys,[5] each approximately 4-hours long and based on Garth Ennis and Darrick Robertson’s quasi-satirical superhero drama comics. [6] The primary audience of audiobooks are sighted users, hence the occasional lack of detail in narration (Shifrin, n.d.) and the fact that audiobooks capitalise on visual media synergies; the two titles above coincided with the highly successful launch of the TV series on Netflix (2022) and Amazon Originals (2019-2022) respectively. A more nuanced approach is instantiated in the “blind-assassin-hero-with-superpowers” audio comic/drama Unseen (2019), created by blind artist Chad Allen for both sighted and BPS audiences. Unseen is complete with a teaser and audio introduction by Allen; a rustling-paper sound effect indicates panel change and the action is professionally performed by male and female voice artists; it features elaborate sound effects and music, part of which (drumbeat and flute score) recalls videogame ambient music.[7] The female narrator follows the action of characters and guides the listener with descriptions on the setting, mood and perspective on each scene.

Perhaps a special category of the audio medium is that of the written-to-be-mechanically-spoken alt(ernative) text. Alt texts are descriptions of images embedded in code so that the descriptions can be pulled up in screen readers. In a pilot project that took place in 2018, Osolen and Brochu were forced to reconsider their practice after a National Network of Equitable Library Service patron requested not the typical book formatting job, but an accessible version of Kirkman and Moore’s horror graphic novel The Walking Dead: Volume 1 Days Gone By (2003) (Osolen and Brochu 2020: 109). This led to a change in their workflow, which they modelled after film AD guidelines and the work of an experienced comics describer-publisher (Guy Hassan): they formed a co-authoring, co-editing duo of alt text authors whilst integrating feedback from users with reading impairments. Their output included a description of The Walking Dead based on the principles of objectivity, brevity, relevance, plus introductory producer’s notes with explanations on page and panel configuration and other formal or narrative specificities (textual effects, point of view/angle) (Osolen and Brochu 2020: 112-113). Despite the vicissitudes of human resource, time and capital, this workflow optimised user engagement and experience. With a view to spoken production quality and further customisation, Lee et al. (2021) have tested a prototype reader system that incorporates eBook/audiobook descriptions and benefits from varied voice output (Amazon Polly); the system allows BPS users to change reading units (panels, strips, pages) and to filter out information they might not need (e.g. panel number).

Customised comic art AD in the spoken medium will be discussed in the next sections, but its duplication under the audiovisual category is intentional. Here it refers to conventional/mass-produced film AD. Audiovisual products are particularly effective in acclimating audiences to a broad range of genres, such as Brian K. Vaughan and Pia Guerra’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi book series Y: The Last Man (2002-2008), which aired as Hulu’s action-drama series (2021), or Hajime Isayama’s dark fantasy tankōbon books Attack on Titan (2009-2021), which have been adapted to an anime TV series (2013-present) and four anime films (2014-2020). Thanks to AD quota requirements in different locales, BPS viewers can autonomously explore a plethora of similar adaptations and keep abreast of the latest, high-grossing products.

An inter-related area is that of the distinctly uncategorisable motion comics. Contemporary formats of motion comics started experimentally, became monetised and declined, all in the short period between 2001-2014 (Morton 2015: 355-356). With the help of modest budgets, small production teams and animation software, these comics can feature variable degrees of intra- and inter-panel animation, read-out text and soundtrack (Morton 2015: 356-357). Motion comics are nowadays a non-commercial, fan-based enterprise. As noted in the credits of a 13.08.22 Star Wars YouTube channel:

This comic book dub is a fan film. […] We make no claim of ownership to the source material. This video was produced for noncommercial use, to be enjoyed by ourselves, fellow fans and the original creators as a tribute to Star Wars.[8]

Motion comics are not specifically made for the blind. However, they could be repurposed, provided that descriptions are detailed enough.

Tactile comics interrogate the methods of creating comic art as well as the ways of understanding it through active tactile exploration. Thus, on one extreme, there are examples such as Philip Meyer’s Life (2013), a story of “an individual moving from solitude to companionship to family and then back to solitude and finally death” (Christopher 2018: online). The story is colourless and each character (a simple, tactile circle), each panel and page are represented by a braille-inspired, embossed/perforated paper format. The book comes with a conventional braille and print introduction explaining the format of the book.[9] Meyer’s art capitalises on tactile input and is aimed at all readers, irrespective of sightedness or prior comic book experience. Other works, on account of being less abstract and/or mimicking extant comics, constitute “translations” of such pre-existing material. In 2018, the Charles M. Schulz Museum created two tactile versions of one of the earliest strips of Charlie Brown and Snoopy (1951). The first set consisted of raised lines and braille descriptions and the second consisted of progressively complex relief textures and materials, not unlike translations of paintings that help visitors understand the volumetric and stylistic values of a work of art (Secchi 2022: 133, 135). The Schulz museum offers visitors the opportunity to consult Schulz’s Twin-Vision version of Happiness is a Warm Puppy (1962), which features braille text and raised paper translations of the art.[10] In between these two levels of abstraction, one may place Boat Tour, developed collaboratively by artist Francesc Capdevila Gisbert, blind participants of Blind Wiki and a co-curator of the Catalan contribution to the 57th Biennale of Venice (2017). This abstract comic uses introductory braille and print legends (listing shapes, such as “boat” and textures, such as “Water,” “Echo”) and embossed forms to represent the flow of a boat along a canal and to evoke the sound and sensation of a trip (Fraser 2021: 742-743). As such, it simultaneously draws on the tradition of wordless comics, destabilises the idea that comics are a visual art (or that a boat trip is a strictly visual experience) and experiments with traditional forms (the canal dividing the work in two panels is in fact part of the diegesis) (Fraser 2021: 739).

The last category entails the most experimental accessible media in terms of tech-user interaction. Vizling, for instance, an application compatible with tablets, may read texts out loud; or it may employ screen-touch responses (vibrations) to guide the reader through the narrative arc and the Z-shaped, panel-to-row reading direction on the page; for more customization, there is an exploration mode whereby the reader can touch any part of the page to get relevant contextual spoken descriptions.[11] Accessible comics have also entered the sphere of virtual simulation. Headgear fitted with a reaction wheel array developed at MIT creates sensations in the inner ear (our centre of balance) that mimic the acceleration or forces a user typically feels in physical actions, such as jumping, pulling, falling and kicking.[12] Combined with 3D-sound of the Daredevil audiobook, these sensations offer an immersive experience from the point of view of the superhero.

Mapping out accessibility in the field of comics is useful in highlighting unity in diversity as well as feasibility. Not all BPS users and not all cultural practitioners or museum staff may be aware of the full range of options available. Academics from different areas may also be equally unaware of the extendibility of the medium of comics, which may result in fragmentation and lack of development. A map such as the above could help with awareness raising. It also shows possibilities, delineating a transcreation brief congruent with semiotic, technological or social specificities suitable in each case. In a museum context, for example, interpretation requires making decisions vis-à-vis accessibility medium, managing medial overlaps effectively (say film-comic book), setting realistic timescales and levels of message customisation. These possibilities may be regarded in a positive way, by de-emphasising the constraints of visuals and instead adopting a flexibly logo-centric (written/spoken word) conceptualisation of comic art. An accessibility brief for human-voiced AD for comics will be presented in the next section, from the angle of important interactions serving the interpretation of comic samples as distinct display items.

3. Medial transformations in a museum network

Comics have traditionally been labelled a medium, which, in Comics Studies may entail any of the following: the system of semiotic resources used to convey information (image/language); the physical instruments of artistic expression (and related technologies); the social norms underpinning production, distribution and reading (Mikkonen 2017: 16-18). Debates on the definition or specificity of the comics medium are not entirely settled, except through a realisation that comics convey messages in a historically derived, socially agreed upon manner and that they bear affinities to both literature and cinema. More crucially, as already prefigured in Section 2 from an accessibility perspective, a prototype logic applies. Comics normally combine image and language to tell a story, they use panels as units of time and pages as larger units of composition, thus allowing readers a certain level of autonomy in reading linearly or across several panels (Mikkonen 2017: 20).

A more theoretically nuanced perspective may be found in Bartosch’s (2016) application of Latour’s sociological model of Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to comics mediality. To summarise key points, ANT suggests that the interaction between heterogeneous human and non-human actors (e.g. texts) induces action, and actions are consequently linked to further actions, to form a network of goal setting, identity negotiation and expression of agency (Latour 1996: 336-338). Forming alliances and setting goals is contingent upon a network, which may grow in size or evolve unpredictably, depending on the activity of its actors.

Mediality too, Bartosch claims, consists of shifting alliances and is underpinned by a process of materialisation, or distribution of agencies between human and non-human entities so that “bodies, objects and subjectivities emerge as relational effects” (2016: 245). To illustrate, Brian Fies’ four, fictitiously old comics accompanying his book Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? (2009) was the result of a network: the creator (Fies), his editor, paper suppliers to the publishing house, old newsprint paper, a scanner, image editing software. Fies modelled his comics after the style and format of different ages of comics production, complete with progressively phased out stains and printing blemishes, (i.e. indices of ageing and cheap production). This effect he achieved by scanning old paper (the creator and editor had to negotiate with paper suppliers to secure it), by uploading the scanned paper image as a layer, which was then used as a canvas to create the books (Bartosch 2016: 246-247). Mediality here is tantamount to tracing the relations between (non-)human actors.

What Bartosch suggests about creating original works, Translation Studies scholars have said, mutatis mutandis, about the transfer of works across languages. Agents with a specific interest in foreign literature, for example, negotiate a space for it in a given target culture through negotiation and contingent alliances (Buzelin 2005: 207)—nowadays, one may add the deployment of technology, be it neural machine translation or sound/image-editing and subtitling software. Such an approach destabilises the text-context and subject-object distinctions Latour was so keen to challenge (Latour 1996: 337-338). Most importantly, it is an idea that can be extended to a museum setting, be it in an official exhibition, or, as in this case, a workshop activity that goes beyond the typical outreach activities and workshops organised by the museum. Following the actors in a contingent network here may help shed light on the translation process (project brief, collaborative work, skills required), the translation product (physical format, creative language transfer) as well as on how a museum’s outreach agenda may be served by engaging audiences and by creating texts accessible to those with limited or no proficiency in the official language of the museum.

Creating AD comics for a museum propels this idea further—in terms of experimenting with a medium as well as in terms of offering access to audiences with limited or no proficiency in the visual language of comics due to their disability. Creating AD comics was possible after a network formed: an academic, a curator, comic artists, an audio describer, BPS visitors, electronic and/or hard copies of comics, voice recording software, voice editing software and a laptop with speakers. The project was instigated after I directly contacted the Marketing Team and the curator of The Cartoon Museum in London; my personal motivation may be traced in my own experience of AVT postgraduate programme directorship and academic experience in comics research/networking events (in the last 15 and 6 years respectively). My role ultimately was one of “selling the idea,” sourcing participants and ensuring deliverables were produced on time. Thus the curator was supportive of the idea of comics AD. I consequently placed adverts in the newsletters of two London-based charities supporting BPS communities, in relevant social media groups used by BPS communities and in (snowballed) professional network groups of two comics publishers and two Comics Studies academics known to me. The audio describer is a former colleague whom I contacted directly. The entire project lasted five months: three months for recruiting participants and two months to conduct interviews, commission the AD and display it.

In the first phase of the project, a focused interview (1 h 40 min. long) with four comic artists, the audio describer and the curator took place at a hired studio of The Cartoon Museum (round table format with two digital recording devices used from opposite ends of the table). One week before the interview, artists were primed to expect a question on audiences of comic art and were asked to bring along one of their representative works. Once at the venue, all participants were asked a single question: how they imagined a comic art exhibition for BPS visitors. They freely discussed this responding to each other’s comments with minimal intervention from me.

The second phase of the project entailed the transformation of comic excerpts into audio description. Three of the four comic artists agreed to send samples (as .PDF or .JPEG). Excerpts were selected by the artists and/or myself and the audio describer (see Section 4). The audio describer had the opportunity to ask questions about the art in each case, she authored the descriptions and sent those descriptions to the creators as .DOCX files for feedback. She then performed the descriptions, generating discrete .WAV audio files corresponding to pages/panels in ADEPT (AD software). After receiving the audio clips, I used Audacity (a sound editing application) to splice them together and ensure sound quality was consistent throughout. The audio describer was finally interviewed about her work via a video-conferencing platform (37 min.). The main aim of the interview was to ask her questions on AD practicalities: introductory, professional background-related questions and concluding questions on her views regarding the outcome were asked too.

The third phase took place in a hired studio of The Cartoon Museum with BPS participants, a room with ample space (can host 30 people) and a big table in the middle. Out of the eight participants who responded to recruitment messages, two opted out in due course and four committed to a mutually convenient date. The sample excerpts/chosen pages of comic art were colour-printed in A3 sheets and hard copies of the (physical) comics were available (placed on the table) in case participants wished to consult them. Participants were met and greeted at the entrance of the museum and sat at the table of the studio (each one was accompanied by a sighted friend and in one case, a guide dog). They were subsequently asked questions about their degree of visual impairment (not ascertained in advance) and museum-going habits. Then they listened to each AD audio clip (out of a laptop with speakers) and were asked to evaluate it. Finally, they were prompted to offer their thoughts on future prospects of this type of AD. The listening and the interview parts lasted 21-22 minutes each (i.e. the entire session was close to 44 min. long). The only exception was the interview of one participant, who identified herself as an expert user of AD—she was more (constructively) critical and expansive in her interview, which lasted 33 minutes. Interviews were done in tandem, and after an interviewee finished, museum staff gave them and their sighted partners an introduction to the museum and the current exhibition (this latter activity was not part of the official study).

All sets of interviews (focused and individual) were transcribed and analysed in MAXQDA, using a combination of in-vivo, descriptive and values/emotion coding (see Saldaña 2012). In what follows, I will trace the creative processes and impact, in phase two and three of this five-month project, in the AD product and the interviews with those involved. The first phase (to be explored in forthcoming work) will only be cursorily mentioned, given the scope of this article.

4. Creating AD comics

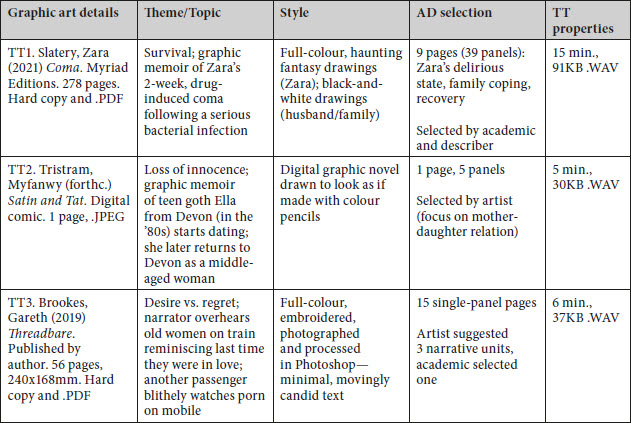

Table 1 offers an overview of the comic art, excerpt selection and the AD target texts (TTs), in the order in which they were played at the museum.

Table 1

Comic art selections

Excerpt selection was made either by the artist at the outset (TT2), with the suggestion of the artist (TT3) or by the describer and me (TT1). All TTs are admittedly longer than typical written/audio museum object descriptions.[13] This was because of a pre-production perceived need to contextualise stylistically different works as well as introduce coherent samples of narrative arcs.

In order to gain a better understanding of the creative process, the audio describer interview will be discussed. The interview shed light on two themes: AD profile (sub-themes: knowledge, AD skill, personal investment) and scripting approach (sub-themes: priorities, working with others). In terms of profile, this is a describer with limited/passive knowledge of graphic novels and fragmented knowledge of bande-dessinée comics. Yet she is currently authoring a new standards document for the European Blind Union, she has over 30 years of experience in film AD and has worked with museums twice. For the latter, she relied on the domain-specific knowledge of curators. Such a collaborative mindset became relevant in comics AD too. Indeed, frequent mentions of the opportunity to collaborate with artists and the joy of discovery (graphic novels) point to her motivation to participate in the project in the first place. Further evidence of personal investment can be seen in statements on social relevance:

Everything should be as accessible as possible, and comics certainly have been ignored […] and it’s a pity […] we have to fight. It’s a question of finances, it’s a question of all sorts of thing, but first and foremost, is there going to be an interest?

audio describer interview transcript

The quote additionally points to a typical skill in AD, knowing the target group (ADLAB PRO 2017). More specifically, before the interview, the describer tapped into her personal network. She took the initiative of reaching out to BPS people she frequently works with in order to gauge their opinion on comics AD. She found out that they were more familiar with funny comic strips read out to them and that they were uncertain about the gains of having a longer, serious, unfamiliar format. BPS participant interviews (see Section 5) partially confirmed this view.

With respect to a scripting approach, the describer referred to a typical dual responsibility: on one hand, to preserve artistic intentions (which can be labelled as loyalty) and on the other, to achieve clarity for BPS audiences (coherence); this dual responsibility requires one to be “neutral without being disinterested,” she added. She also noted that in film, there is ample paratextual material to consult at the research stage and yet the describer has the freedom to de-select such information and to describe what they see (objectivity), without intruding with constant commentary in between the unfurling film dialogue and other sounds (economy), i.e. by “letting the film breathe,” as she put it.

When I prompted the describer to comment on the three comics, there was a sense that the above-mentioned priorities translated in slightly different ways. There is freedom to describe the plot and aesthetic design as it is a static medium, yet the onus is on the describer to create a coherent message that “makes the image come to mind through words.” She contrasted other gallery artefacts to comics, which do not come with a touch tour to complement the audio. She therefore felt that text in comics AD should be free-standing, complete and have a number of words that does not overburden the listener (saying something concisely is a key linguistic skill; ADLAB PRO 2017). Crucially, objectivity was linked to the creators’ intentions, which render comics more complex than film, she conceded. Conveying intentions requires collaborative work:

You need to be able to explain, you know, the thinking behind the static image because it’s not necessarily totally obvious […] I would have struggled you know if it’s just been up to me to try and work out what things are, and that was fantastic.

audio describer interview transcript

More generally, the report contains various references to “saying the right thing,” “factual correctness,” “capturing [authorial] intentions” and “understanding the emotions.” These are comments that chime with an acknowledged clash between standard AD guidelines on objectivity and the inherent ambiguity of museum artefacts, which in their turn are part of the cognitive, emotional and social experience derived in a museum setting (Hutchison and Eardley 2019: 46, 51). The describer was able to address this issue by following the discussion in the focused interview and, thereafter, by posing questions to and getting feedback from artists via email. Questions and responses were collected (Gareth Brookes, the ST3 author, and the describer had a phone conversation, about which the describer was asked at the interview). Feedback helped the describer: i) have all information on the creative process for each piece; ii) understand symbols; iii) verify place names and verify/correct names and age of secondary characters; iv) disambiguate panel background.

Feedback given to the describer, in conjunction with the scripting themes identified above, are highly reminiscent of the call for “mindful translators” who keep audiences “contexted” in other parts of the creative industries (Katan 2016: 71, 84). To paraphrase, contexting may entail explaining field-specific terms or cultural references, explaining aspects of the (visible/invisible) environment (actions, beliefs, emotions), adapting style or layout and changing the message orientation (e.g. an incomplete message relying on context vs. information fully present in the text) (Katan 2016: 84). There are several cases of such mediation in comics AD in this project. Here I will discuss representative examples that hark back to actions in the network that has formed around The Cartoon Museum.

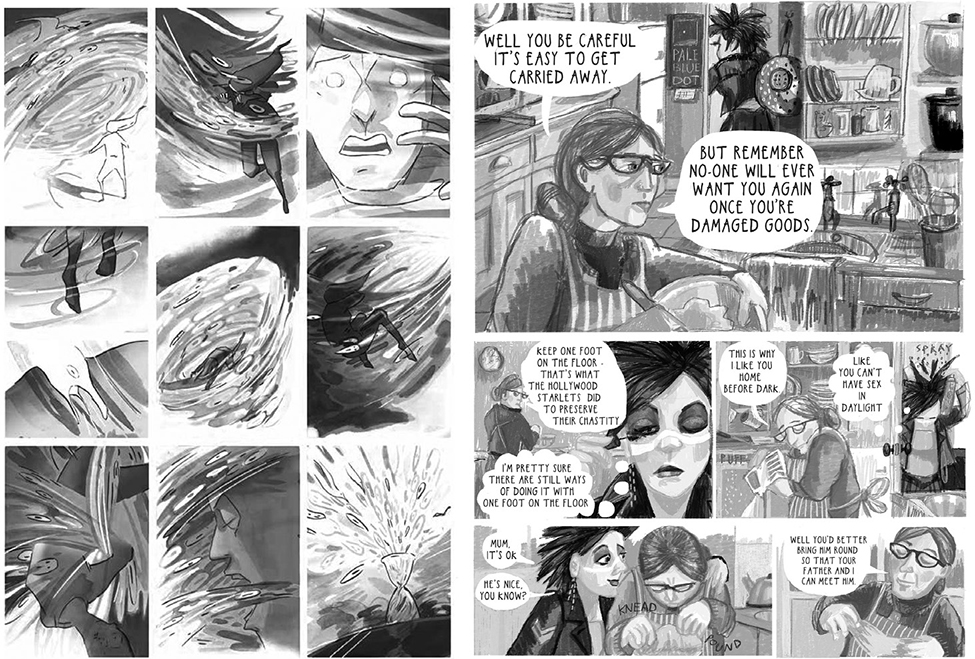

Immediately on starting to work on the descriptions, the describer was faced with visual metaphors, especially in TT1. This prompted her email questions about three specific forms: the shadow of a bird, a monster and an hourglass, the latter appearing in the last panel of the page in Figure 2. The artist explained: the hourglass is the pain and pathogen tornado rushing her into an hourglass; the monster is the coma—in her comments on the first AD draft later, the artist recommended replacing “monster” with “benign beast or creature [… as i]t is both protective and helpless & I’m carried in the belly of it” (emailed feedback by comic artist); the bird is a circling crow symbolising death. For further reference, she attached a map labelling all creatures in Coma. At this point, I was also able to email an excerpt from the focus group transcription where the artist talked about her art, making a reference to visual metaphors and this page in particular:

[…] pain is measured as one to ten and I think this is kind of like a […] way of describing something that’s so visceral. So I was thinking more about sound and, for me, my ten is like a thousand seagulls screaming inside you, whereas a one might be the hoot of an owl. […] it’s a nine-panel grid, the colours are very cool, quite cold. I’ve got a figure that’s at the base of a tornado and is being blown by that tornado. And in that tornado are seagulls and what look like the eyes of seagulls but they’re actually symbols for pathogens which are not dissimilar to the eyes of the seagulls kind of, like, close up.

Slattery, focus group trascript emailed to audio describer

Another artist present at the group discussion conceded: “I never noticed that about the seagulls’ eyes” (Tristram, focus group transcript). Visual metaphors were opaque even to a professional in the field who has read the work several times. Interactions with the artists allowed the describer to pinpoint thoughts, sensations, emotions and beliefs relevant to each panel which would not readily be overt to a reader.

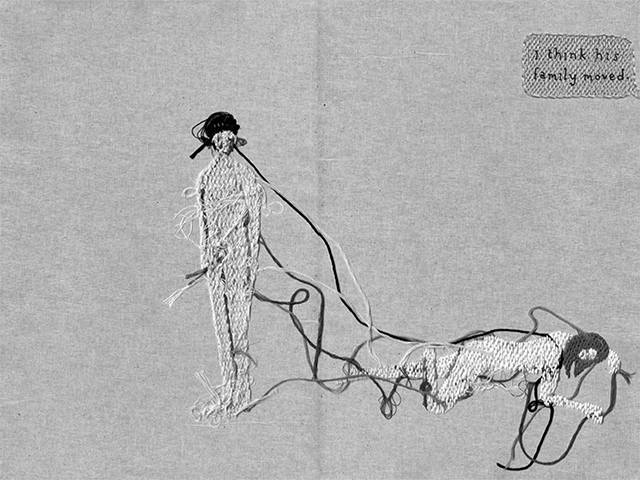

Figure 2

Coma, p. 18 (left), Satin and Tat, n.p. (right)

Figure 3

Threadbare, verso-recto, n.p.

The below excerpt comes from TT1, the piece that took the describer the longest, that is, two days to complete (as comparison, a two-hour film typically takes her three to five days). To paraphrase her, for films she resorts to direct writing (Elbow 1998: 30-31), followed by revision only when her instinctive, linear drafting (rooted in her long film AD experience) proves to be ineffective in the filmic context. Here, however, the opacity of authorial intentions ran counter to her head-start approach. Visual metaphors in particular rendered TT1 the most challenging of the three. A closer look at the first and last panels of a wordless page in Coma (Figure 2), rendered in 119 and 34 words respectively, may shed light on problem-solving:

In the first panel, in a simple black-line drawing, a small slender female figure with long hair flowing behind her, watches helplessly as a tornado of grey and white circular brushstrokes, bowls towards her; a gull, with its piercing eye, caught in its angry waters, looks like the eye of a storm. The gull, Zara tells us, is her inaudible way of signalling pain, on a grid from nought to ten. One shrieking gull is unsettling, several shrieking gulls represent bone-crushing agony. However, the gulls within the gushing water not only represent pain, but also symbolise pathogens. As the tornado gains strength, they become skulls and then gulls once again as her body is twisted and contorted with pain.

[…] The final image on this page is of an hourglass or a sand timer with water and seagulls rushing down into it. The timer represents the brutal speed and ferocity of the infection.

audio description text; TT1 Coma

The description is front-loaded to frame the interpretation of all metaphors on the page. A web of semantic relations assists interpretation. Words signalling the intensity of weather phenomena (“tornado,” “angry waters,” “eye of the storm,” “gushing water”) swiftly morphs into the author’s intended sound perception (“inaudible,” “shrieking gull/s,” “bone-crushing”) and the illness itself (“pain,” “grid from nought to ten,” “agony,” “twisted and contorted,” “pathogens”). The AD for the final panel qualifies intensity with time (“hourglass,” “sand timer,” “rushing down into,” “brutal speed”). The excerpts are dotted with sound games, such as the repetition of /l/, /s/, /f/, /b/ (see first utterance). Although a detailed sound act (Bosseaux 2015) analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, the following characteristics apply to the delivery of the above: soft voice, mid-to-low pitch, narrow range (but not monotone), slightly nasal, slow-to-medium tempo and generally smoothly flowing rhythm (except for brief pauses at sentence-final positions for emphasis, e.g. before “—bone-crushing agony,” “—of the infection”). Delivery, coupled with the intensity-signalling nouns/adjectives above, convey drama and sombreness. It is what the artist intended. A slippage in reporting (“Zara tells us”) and the use of verbs of representation (“signalling,” “represent/s,” “symbolise”) tether the description to this intention.

Each piece starts by acclimating listeners to the themes and style used. This the describer achieves by resorting to her own (world) knowledge, audio description experience, background research and interactions with the artists. As such, introductory texts constitute bindings, or texts engendered through a network of interactions and multiple agencies, which in their turn elucidate relations between a text-object as cultural event and the discourses of the time (Harvey 2003: 177, 180). The introduction of Threadbare (TT3; Figure 3) includes an almost verbatim (bar the last sentence) iteration of the artist’s email message to the describer. The excerpt below frames interpretation through a key theme: the incongruity between what is/could be. The theme is undergirded by the belief that technology may exacerbate existing tensions:

[…] The tactility of the book, embroidery behind glass, heightens the idea of desire and regret, of not being able to touch the embroidered surface in the same way you can never go back and re-live the embodied experience of the desired thing; also the tactile paucity of internet experience, watching people have sex via the smooth cold screen of a smart phone on a train. You look at images that create desire but which you can’t touch.

audio description text; TT3 Threadbare

Semantic signification helps instantiate the theme: time (“go back,” “re-live”), emotions (“regret,” “desire,” “desired thing”), visual perception (“behind glass,” “surface”) and touch (“tactility,” “smooth cold screen,” “touch”). The comic book was subjected to medial transformation (embroidery-to-soft-bound book) to only appear touchable or within our reach, like other things in life. At the group discussion, Brookes described his art as a “provocation,” adding that what might need to be salient in AD is: “the touch, the feel, the process, I’ll say that it would probably need to be said the artist did this and that. The problems that that brings with it” (Brookes, original emphasis). Just like subtitlers or film describers who have recourse to director interviews and, on very rare occasions, preproduction scripts or story boards (Romero-Fresco 2019: 183), so too the comic book describer in this network ventriloquizes the creators to bring artistic themes to the fore.

A final, crucial area of mediation is character introduction. Characters take a physical form, perform actions and have distinct narrative missions, all controlled by the genre at hand (Asimakoulas 2019: 130-131). They are entities with a visible outside (albeit stylised) and an assumed inner self, which is the source of their intelligence, volition and emotions (Mikkonen 2017: 179). Comic artists (progressively) reveal characters to readers through actions, mental states and words, and through the illusion of objective showing, even though characters are anchored to ever-present elements of subjectivity and telling (Baetens 2013: 86-88): style of drawing; the interaction, sequencing and variety of words and images; size and framing of panels (e.g. close-ups); layout; plot (often crafted to elicit empathy). Readers, on their part, decode characters on the basis of this subjective showing-telling as well as their own experiences of similar situational contexts to the ones experienced by characters, their experience of similar characters in other cultural products and their reading (or listening, in this project) of paratexts (Mikkonen 2017: 180-184).

Comics AD in the museum is short, yet characters must somehow be “revealed” if readers are to channel their inferences with respect to plot and the grander themes tackled in each book. The technique used by the describer, and which is especially pronounced in the shorter of the three pieces, TT2, is an inverted pyramid structure: theme, topic, style, setting, characters, character perspectives.

[…] In the artist’s own words, her book is a story of lost innocence interwoven with the rich details of her time, in terms of pop culture, music, hairstyles, fashion and so on […] [THEME] The heroine is Ella, a self-styled teen Goth […] we observe her relationship with her mother at their home in Devon, far from the madding crowd at some point in the 1990’s [TOPIC] There are six panels on this page, the largest taking up half the page […] The style of illustration is loose and sketchy, vivid and detailed, in subtle, non-primary colours [STYLE] […] We are in a country kitchen, but though we only see a corner of it, it looks very familiar and also very different from the hi-tech styles of today. There is a terracotta tiled floor, pale wooden kitchen units on the left-hand side […] [SETTING]

audio description text; TT2 Satin and Tat

This initial part of the AD explains the theme (loss of innocence) and the topic, the who, when, where. The topic contains clues to the main character’s traits. Key phrasing, “self-styled, teen Goth,” places Ella under a specific social group, foreshadowing her appearance, habits and intensity of adolescent convictions. Then follows the style of drawing, which generally constitutes the imprint of the comic artist’s subjective narration or even a clue to the situation characters find themselves in. Exceptionally, graphic style here carries extra narrative significance. Vivid drawing, a flashback in the book, is later contrasted with middle-aged Ella’s perspective in black-and-white. This distinction was not divulged (or remembered) by the describer. On the other hand, “loose and sketchy,” “vivid and detailed” draw attention to a dynamic relation between type-like qualities and individual-like qualities (Mikkonen 2017: 192): Ella the adolescent rebel vs. Ella the main character, an individual with intense, changing emotions that any reader can relate to. Continuing with the setting, the describer adds her own evaluation, thus both demarcating temporal timelines and helping imbue the scene with a nostalgic perspective of cosiness (“looks very familiar”).

After this opening, the two characters are introduced:

How to describe Mum? For anyone who remembers The Good Life, this mum would fit right into that setting. This is a woman who likes to bake and clearly doesn’t spend much time looking at herself in a mirror. You feel this is a woman who has more important things to be thinking about, the state of the planet, banning the bomb, yes, and looking after her child. Mum has long dark hair with a few grey streaks, tied back in a low bun and wears dark-rimmed spectacles, no make-up or jewelry. She is wearing a grey green turtlenecked top with a brown cardigan and a blue and white striped apron on top. The overall effect is one of dowdiness and dressing older than her years. [CHARACTER 1] Her daughter in stark contrast is a girl who is living the moment, for whom image is everything. She has spiky black hair, dangly earrings, black eyebrows, lashings of purple eye shadow giving her the look of a panda. She’s wearing black lipstick, a short black army jacket over a pale t-shirt and short black skirt and she’s getting ready to go out on a date. [CHARACTER 2]

[…] She continues in panel two, looking over her shoulder at Ellie whom we now see front on in close up as she puts on her mascara. [STYLE] “Keep one foot on the floor, that’s what the Hollywood starlets did to keep their chastity.” [ASPECT OF CHARACTER 1] Ellie’s thought bubbles out of her head: [STYLE] “I’m pretty sure there are still ways of doing it with one foot on the floor.” [ASPECT OF CHARACTER 2]

audio description text; TT2 Satin and Tat

For the mother, the describer took the risk of creating an analogy to The Good Life (1975-1978) (see Section 5). The meta-comment (rhetorical question) at the very beginning constitutes a salient sign of subjective telling, also facilitating a more varied and dialogic style in the description. The contrastive mother-daughter perspective is relayed from the inside out, as it were. First, each character’s beliefs are laid bare. Hyperboles zoom in on their respective values: “state of the planet, banning the bomb,” “lashings of purple eye shadow giving her the look of a panda” are key phrases. The mother is down-to-earth, with a collectivist mindset and a distinct long-term orientation; she clearly places emphasis on values rather than external appearance. Her daughter, on the other hand, is self-absorbed, has a short-term orientation and indulgence is of paramount importance to her. External appearance follows, with particular attention to each character’s hairstyle and fashion options. Panel two presents an interaction where these antitheses play out. The mother metes out conventional pieces of advice from the background of the panel. Delivery in AD is tense, mid-to-high pitch, wide range (giving mum a more sing-song intonation quality), in relatively fast tempo. Ella’s response is lax, low pitch, in narrow monotone range and slow tempo. Such features serve as indices of age, attitudes towards life and levels of engagement. Ella’s character, for instance, comes across as bored and focused on an activity far removed from the musings and truisms of her mother. As performed words, thoughts and described interactions start to accrue, characterisation may be achieved.

5. Visitor reactions: “making it accessible to somebody like me”

Interviews with visitors at The Cartoon Museum generated three themes: cultural consumption habits, AD performance (sub-themes: delivery, style), visitor-as-subject (sub-themes: emotions, comprehension).

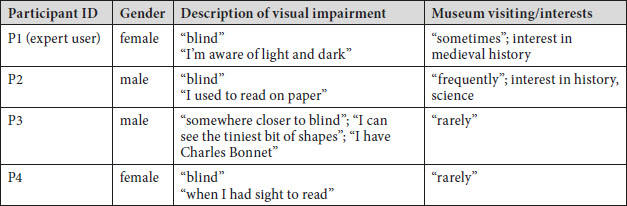

Interviews yielded brief moments where participants (Table 2) could spell out their experiences with or general perception of museums. Two presented an object-oriented, self-exploration perception (see Stylianou-Lambert 2011: 411-412): P1 “sometimes” goes to museums and heritage sights (cathedrals) as she has an interest in medieval history; P2 does so “frequently” and enjoys science museums or history museums with touchable objects and AD provision. By contrast, two visitors had a perception of exclusion; P3 and P4 “rarely” visit museums as they find the lack of AD and difficulty of physical access off-putting.

Table 2

BPS visitors to The Cartoon Museum

All participants described AD as a crucial service which, when available and done well, can transform the experience of a cultural product, be it a film, a play or a museum exhibit. Two participants suggested that The Cartoon Museum adopt a nuanced approach to future exhibitions. This, according to P2, can entail: addressing individual taste (fantasy, adventure), integrating multi-sensory experience and activities for families, making the space more accessible physically (braille, large-print, lighting, easy stair-access); P1 suggested museum staff upskilling by sharing good practice (in AD) and saw a need to bridge two cultures: the “counterculture,” as she put it, of comics and the culture of the visually-impaired; as she said, it is an issue of “comics coming and finding out, you know, looking at VI[the Visually Impaired] culture, looking at some of the visuality within our culture and understanding what they already do do that connects with us” (P1). Similarly, she noted that future comics AD must be tailored (see critique below) to the needs of those who have had a stroke, were born blind, have facial blindness, neuro-processing difficulties and developmental disorders such as Asperger’s Syndrome (P1). An unexpected response to this comment came from P3, a visitor with Charles Bonnet Syndrome, which causes visual hallucinations. He appreciated the diversification allowed by AD:

So, them hallucinations can be on top of my daily visuals. So, having something like this [AD comics] can sort of distract you quite easily into something more engrossing.

P3

In terms of AD performance, three participants (P1, P3, P4) characterised delivery as “very good.” They found the describer’s voice engaging and appropriate for key moments in the narrative:

[I]t’s a human voice, not a mechanical one so […] bearing in mind most of us have mechanical voices throughout our life, it’s a pleasant change and the voice was engaging, you know, it was tonally interesting, the way that different things were emphasised or not emphasised.

P1

[…] the storyline was like serious [in TT1…] And I think on reflection now, you know, the tone of the delivery reflected the storyline.

P4

TT2 (Satin and Tat) received the most positive comments for delivery; words used by the participants included, “clear,” “soft delivery,” “slow.” Slow delivery was equated to a better pace. By contrast, lapses of fast delivery were critiqued (P1, P2, P4), especially in TT1 (Coma), the longest AD comic. P1 noticed a gradual increase of tempo in TT3 (Threadbare) too, which she critiqued. P2 was the most critical of all participants and felt minimally engaged. As will be shown below, this is due to a combination of factors rather than solely tempo of delivery. Finally, P3 detected a higher-than-normal treble in the sound quality in TT1, which he would normally not prefer.

The style of language used was generally praised; positive attributes were “clarity” (P1, P2, P4), “humour” (P4), and “simplicity” (P1, P3), especially in short words or phrases one can instantly relate to physically or emotionally (“gushing water,” “animated face” in TT1, “warm hug” in TT2, “deliriously happy” in TT3). Suggestions for improvement included the need to balance word count detailing emotions vs. word count dedicated to the setting in TT2 (P3, P4).

The interviews contained various comments on the subjective experience of AD comics vis-à-vis emotively marked language in the reports revealed a variety of reactions. Thus, P3 and P4 enjoyed the experience, with P3 pointing out the novelty of the medium:

I mean, first time I’ve listened to something like that, apart from talking books […] I like this because it’s making it more accessible to somebody like me, who just thought it was a bit, sort of, not my sort of thing.

P3, added emphasis

Positive references were made to the value of realistic scenarios presented in graphic memoirs (P1, P3, P4), with P4 now harbouring a curiosity about the rest of the longest piece (TT1), which she would like to listen to in the future. By contrast, P2, who declared his allegiance to sci-fi or fantasy genres, was alienated by the characters and the plot, especially in TT1 and TT3: he “was not impressed,” as he said, could not relate to the story and did not feel motivated to listen till the end. P1 enjoyed the experience overall; she praised TT3 for the “powerful image” it conjured up as well as the tactility of the medium and its presentation. Unlike P3 (see quote above), she felt frustrated by the fact that AD did not fall squarely under the tradition of audio books, which affected comprehension. In her view, the AD contained specialised, opaque references to style (“brushstroke,” “watercolour,” “italics”) and referred to sequences of “panels” in an unsystematic way. Thus, she found it difficult to understand self-referential artistic elements in the midst of run-on narration and performed dialogue.

Here lies the greatest challenge facing the describer. Sighted individuals are assisted by their life-long comics literacy to appreciate interactions between dialogue, visual narrative elements and sequencing of panels within a specific layout on the page. This gestalt-like processing of graphic style supports a sighted reader’s sense of units (and rhythm) of reading, formal aspects of design and, ultimately, the subjective telling of a story and characterisation. Converting such multimodal interactions into a monomodal spoken delivery may require further systematicity in the chronological sequencing of panels and the interactions between graphic style and the telling of the story. Two concrete suggestions distilled from P1’s comments are highly relevant here: describing the page layout, reading orientation and panel transition at the beginning of each page so that a linear flow of images is understood; using bridging sentences when referring to aesthetic elements. With respect to the latter point, there are parts where bridging statements are missing (see discussion of “sketchy style” in TT2 in Section 4), but even when links exist, they need to be strong enough. For instance, participants (P1, P2, P3) could not follow how threads of embroidered characters interlocked in TT3 panels. As P3 said, “you know, from the back of the tapestry, the threads coming out, I wasn’t sure whether that was the front or the back at times.” A strategically placed phrase/sentence could strengthen the link between this local aesthetic feature to the artist’s overarching metaphor of neat facades (our presentation to the world) versus threads at the back of calico (our messy feelings), a feature that was explained in TT3’s introduction. Here it must be noted that all participants without exception found introductions to the TTs “clear” especially as they “help set the scene” (P4). Local aesthetic elements may be usefully linked to the overarching frame of interpretation intended by the artist and relayed in these introductions.

In terms of character presentation, the most critical participant, P2, was only able to fully understand TT2, which featured just two characters. His level of comprehension dropped dramatically in TT1 and TT3 where he found multiple characters and varied narrative perspectives confusing. As noted above, P2’s alienation can also be traced in the serious autobiographic genres used here, which he admitted lay outside his personal preferences. Overall, participants were able to “get a sense of the characters [their] thought process […] what they were going through” (P4). They generally found the descriptions clear. In terms of improvements, P1 suggested more description for secondary characters, who she thought remained faceless in TT1 and P3 said he needed more description of the main character when she was in bed in TT1. The same participant noticed the analogy in TT2:

[T]he characters were good, you know. You had a feeling for how she looked in her Good Life look. I suppose in your head, you picture Felicity Kendal wearing that sort of gear [laughs].

P3

The risk the describer took in linking the mother in TT2 to a sitcom character paid off here as it boosted visualisation (possibly enjoyment too). Strategically placed, the analogy activates genre expectations vis-à-vis character appearance, behaviour and development (Mikkonen 2017: 193-194). Genre expectations here are directly accessible, as the visitor has watched the sitcom before. A highly popular sitcom, The Good Life, has had a sustained presence in UK media, including DVD versions (2005-2010) and a “complete collection” audible version released in 2019. [14] Even without direct experience of the programme, there is still the possibility of visitors having fragmentary, passive knowledge of the programme.

6. Conclusion

This pilot study suggested a conceptual map for an accessible ninth art, both a rudimentary awareness-raising act and a positive take on possibilities going beyond fixed picto-centric views of this art. Whilst the rather small body of scholarship dedicated to accessible comics focuses on screen readers, this project innovates by following the route of audio description, which remains terra ingognita both in terms of practice and academic research. This is astonishing, given the volume of AD research in other sectors (especially AVT) and given that comics represent multi-billion industries in hotspots of production (e.g. Japan, USA); fans, creators, businesses and academics acknowledge their significance for technological, genre and storytelling innovation and as barometers of socio-historical circumstances, especially as they address a range of issues, from escapist topics to grand challenges, such as environmental disasters and armed conflict (e.g. Citi Exhibition — Manga 2019; Graphic Brighton festival 2016-2022). Thus, designing accessible comics may facilitate inclusion of individuals with sensory impairment, or, as shown in the (creative team) interviews, offer distinct benefits to neurotypical users (e.g. by bringing to the foreground comic art characteristics routinely missed in acts of superficial/fast reading). Combining accessible comics and audiovisual translation, and adopting a contingent network approach, the study brought together an academic, a curator, four comic artists and a describer in order to explore/extend comics mediality and canvass views on new AD practice. The resulting products, three audio described comics by Gareth Brookes, Zara Slattery and Myfanwy Tristram, were sampled by blind visitors at The Cartoon Museum, in London. Although realistic conditions of a small-scale exhibition have not been recreated, participants worked with a comics museum creative brief, negotiating the way in which original artistic messages could be transformed into an accessible audio format. Close reading of the final produce ant the combined views of participants offered a glimpse into best practice on a global or local level of the AD text:

-

Global (Framing): using introductions to acclimate readers; this is similar to findings in audiovisual AD, where diegetic elements, characters and plot are described in advance (see Fryer and Romero-Fresco 2013); for comics, introductions are effective in explaining the theme, topic and formal/narrative aspects of graphic style;

-

Global (Characters): striking a balance between inner lives of characters and setting descriptions as well as paying attention to main characters, but not at the expense of secondary characters; this finding corresponds with a theory of “following” a certain character to establish narrative coherence (Mikkonen 2017:103);

-

Local-Global (Style): deploying bridging statements locally to connect graphic style in a given panel to the artist’s intention; this finding recalls debates around camera work in audiovisual AD with filmic pace, genre and practitioner views tipping the scales towards inclusion or omission (Fryer 2016:132); comics, by contrast, are precisely appreciated because they are read slowly and by having frequent recourse to both dialogue and visuals; AD users commented on the need to maintain a good flow of reading and to clearly signal crux points where graphic style or perspective changes;

-

Local (Delivery): delivering the audio in slow tempo, with voice modulation that matches characterisation;

-

Local (Language Quality): exploiting figures of speech (both tropes and schemes, the latter including sound games); figures of speech are often associated with creative language use, often seen in AD prepared for other sectors of the creative industries (Fryer 2016: 66-70);

-

Local (Language Quality): using simple, concise descriptions and explaining terminology, an edict repeated in AD guidelines around the world;

-

Local (Language Quality): creating lexical networks in the text that sustain (visual) metaphors; this is a particular feature of comic art as visual metaphors are indissolubly linked to the grander themes of a work and/or the spatio-temporal attachment and character-bound perspectives (Mikkonnen 2017:147).

Given the limited time, scope and resources of this ground-breaking project, networking operated linearly, with the creative teams collaborating first, and blind visitors sampling the art and offering feedback later. This is a limitation that should be addressed in a future project, if co-creation is to be promoted systematically. For instance, it would be interesting to explore how audio describers (in the plural) and (a greater number of) blind visitors can learn from each other and/or how the comics literacy of both groups may be boosted. Despite this caveat, some of the techniques listed above, only materialised because of collaborative work at the pre-production stage. Further avenues to explore would be to generate more collaborations between institutions (libraries, museums, publishing houses), tailoring descriptions to suit the needs of a diverse BPS community, in dedicated outreach activities, ideally in a thematically unified exhibition, or considering using comics AD for sighted users too; the curator of The Cartoon Museum has already committed to using one of the three pieces produced here as a permanent piece so that typical sighted visitors may respond to it. Such a flexible approach would be fully aligned with the general mission of comics as engines of memory creation and enjoyment among diverse, non-elite audiences around the world.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The Expanding Excellence in England project (Project code: AN1999) offered financial support for room hire, interview transcriptions, participant and audio description fees.

Notes

-

[1]

See the Nick Sousanis and the Paul K. Longmore Institute of Disability Studies websites (<https://spinweaveandcut.com/blind-accessible-comics/> <https://longmoreinstitute.sfsu.edu/>); after the project ended in June 2022 and an article was submitted to META in September 2022, Sousanis and Beitiks completed “Comics Beyond Sight” in June, 2023 (https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/06/28/1074341/comics-beyond-sight/); Comics Beyond Sight entails, a bespoke comic panel sequence created for accessibility purposes and then described (with human voice) in six different ways (following different levels of granularity in the information provided in each case).

-

[2]

Comic Book Script Archive. Consulted on September 30, 2022. <comicbookscriptarchive.com/archive/the-scripts>

-

[3]

As discussed by Osolen, personal communication, 04.07.2022; see also Shifrin 2016.

-

[4]

Convert Comic Books to Audiobooks for Blind People. Assistive Technology Blog. Consulted on September 30, 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MaVfnW-F7WM/>

-

[5]

Ennis, Garth. The Boys. Volume 1. Consulted on September 30, 2022, < https://www.audible.co.uk/pd/The-Boys-Volume-1-Dramatized-Adaptation-Audiobook/1648816649/>

-

[6]

Ennis, Garth and Robertson, Darick. The Boys. < https://www.dynamite.com/htmlfiles/viewProduct.html?CAT=DF-The_Boys/>

-

[7]

Allen, Chad. Unseen. Consulted on September 30, 2022, <https://www.unseencomic.com/>.

-

[8]

Star Wars: Lando#4 (Audio Comic). Star Wars Audio Comics. Consulted on September 30, 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i9xvEGsxwP0>.

-

[9]

Meyer, Philipp. Life. Consulted on September 30, 2022 (< https://crlcc.com/life/>).

-

[10]

Peanuts Comic. Lighthouse. For the Blind and Visually Impaired. Consulted on September 30, 2022, <https://lighthouse-sf.org/tag/peanuts-comic/>.

-

[11]

Vizling Comic. Wichita State University. Consulted on September 30, 2022, <https://www.wichita.edu/academics/fairmount_college_of_liberal_arts_and_sciences/english/deptenglish/vizling.php>.

-

[12]

Quach, Tina. Project daredevil. Learning how to make… Consulted on September 30, 2022, <http://fab.cba.mit.edu/classes/863.18/CBA/people/tina/portfolio/week00_final_project_tracker/>.

-

[13]

See average 2.5-minute descriptions on the museum website. Audio App. British Museum. Consulted on September 30, 2022, <https://www.britishmuseum.org/visit/audio-app#how-to-use>.

-

[14]

Davies, John Howard (dir.) (2019) The Good Life: The Complete Collection. BBC Worldwide. Consulted on September 30, 2022 <https://www.whsmith.co.uk/products/the-good-life-the-complete-collection/5036193032745.html/>.

Bibliography

- Aaltonen, Sirkku (2013): Theatre translation as performance. Target. 25(3):385-406.

- Adlab Pro (2017): IO2 REPORT | UNITS: Audio Description Professional: Profile definition. Consulted on September 30, 2022, https://www.adlabpro.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IO2-REPORT-Final.pdf.

- Asimakoulas, Dimitris (2019): Rewriting Humour in Comic Books: Cultural Transfer and Translation of Aristophanic Adaptations. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan.

- Baetens, Jan (2013): Comics and Characterization: the Case of Fritz Haber (David Vandermeulen). Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 4(1):84-91.

- Bartosch, Sebastian (2016): Understanding Comics’ Mediality as an Actor-Network: Some Elements of Translation in the Works of Brian Fies and Dylan Horrocks. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 7(3):242-253.

- Bosseaux, Charlotte (2015): Dubbing, Film and Performance. Uncanny Encounters. Berlin: Peter Lang.

- Buzelin, Hélène (2005): Unexpected Allies. How Latour’s Network Theory Could Complement Bourdieusian Analyses in Translation Studies. The Translator. 22(11):193-218.

- Christopher, Brandon (2018): Rethinking Comics and Visuality, From the Audio Daredevil to Philipp Meyer’s Life. Disability Studies Quarterly. 38(3).

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge (2018): “Subtitling’s a Carnival”: New Practices in Cyberspace. The Journal of Specialised Translation. 30:127-149.

- Elbow, Peter (1998): Writing with Power. Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process. 2nd edition. Oxford: O.U.P.

- Fraser, Benjamin (2021): Tactile Comics, Disability Studies and the Mind’s Eye: on “A Boat Tour” (2017) in Venice with Max. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 12(5):737-749.

- Fryer, Louise (2016): An Introduction to Audio Description: A Practical Guide. London/New York: Routledge.

- Fryer, Louise and Freeman, Jonathan (2013): Cinematic Language and the Description of Film: Keeping AD Users in the Frame. Perspectives. 21(3):412-426.

- Fryer, Louise and Romero-Fresco, Pablo (2013): Could Audio-Described Films Benefit from Audio Introductions? An Audience Response Study. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness. 107(4):287-295.

- Harvey, Keith (2003): “Events” and “Horizons.” Reading Ideologies in the “Bindings” of Translations. In: Maria Calzada-Pérez, ed. Apropos of Ideology. Translation Studies on Ideology – Ideologies in Translation Studies, Manchester: St Jerome Publishing, 43-69.

- Hicks, Veronica and Nichols, Alesha (2018): Woven. remus maurice jackson. Consulted on August 19, 2022, https://remusjackson.com/woven.

- Holland, Andrew (2009): Audio Description in the Theatre and the Visual Arts: Images into Words. In: Gunilla Anderman and Jorge Díaz Cintas, eds. Audiovisual Translation. Language Transfer on Screen. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan, 170-185.

- Hutchinson, Rachel S. and Eardley, Alison F. (2019): Museum Audio Description: the Problem of Textual Fidelity. Perspectives. 27(1):42-57.

- Jiménez Hurtado, Catalilna and Soler Gallego, Silvia (2015): Museum Accessibility through Translation: A Corpus Study of Pictorial Description. In: Jorge Díaz Cintas and Josélia Neves, eds. Audiovisual Translation. Taking Stock. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 277-298.

- Jimson, Kerry (2015): Translating Museum Meanings. A Case of Interpretation. In: Conal McCarthy, ed. The International Handbooks of Museum Studies. Vol. 2. Oxford: Wiley and Sons, 529-549.

- Katan, David (2016): Translating for Outsider Tourists. Cultural Informers Do It Better. Cultus. 9(2):63-90.

- Kerr, Liana (2015): Description of Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. Liana’s Paper Dolls. Consulted on August 19, 2022, https://lianaspaperdolls.com/uploads/watchmen/Watchmen%20Chapter%201%20At%20Midnight,%20All%20The%20Agents.txt.

- Kleege, Georgina (2018): More than Meets the Eye. What Blindness Brings to Art. Oxford: O.U.P.

- Latour, Bruno (1996): On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications. Soziale Welt. 47(4):369-381.

- Lee, Yunjung, Joh, Hwayeon, Yoo, Suhyeon and Oh, Uran (2021): AccessComics: An Accessible Digital Comic Book Reader for People with Visual Impairments. Proceedings of the 18th International Web for All Conference (W4A ’21). (18th International Web for All Conference, Lyon, April 19-20, 2021) Ljubljana: ACM.

- Mazur, Iwona (2022): Linguistic and Textual Aspects of Audio Description. In: Christopher Taylor and Elisa Perego, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Audio Description. London/New York: Routledge, 93-106.

- Mikkonen, Kai (2017): The Narratology of Comic Art. London/New York: Routledge.

- Morton, Drew (2015): The Unfortunates: Towards a History and Definition of the Motion Comic. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 6(4):347-366.

- Osolen, Rachel Sarah and Brochu, Leah (2020): Creating an Authentic Experience: A Study in Comic Books, Accessibility, and the Visually Impaired Reader. The International Journal of Information, Diversity and Inclusion. 4(1):108-118.

- Pérez-González, Luis (2014): Audiovisual Translation. Theories, Methods and Issues. London/New York: Routledge.

- Romero-Fresco, Pablo (2019): Accessible Film Making. Integrating Translation and Accessibility into the Filmmaking Process. London/New York: Routledge.

- Saldaña, Johnny (2012): The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing.

- Secchi, Loretta (2022): “Ut Pictura Poiesis” The Rendering of an Aesthetic Artistic Image in Form and Content. In: Christopher Taylor and Elisa Perego, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Audio Description. London/New York: Routledge, 127-142.

- Shifrin, Matthew (2016): Panel by Panel: Comic Book Access for the Blind. Future Reflections. 35(3).

- Shifrin, Matthew (n.d.): Augmenting the Power of Language. TEDxNatick. Consulted on August 19, 2022, https://www.ted.com/talks/matthew_shifrin_augmenting_the_power_of_language.

- Soler, Silvia and Luque, María Olalla (2018) “Paintings to My Ears”: A method of studying subjectivity in audio description for art museums. Linguistica Antverpiensia. 17:140-156.

- Stylianou-Lambert, Theopisti (2011): Gazing from Home: Cultural Tourism and Art Museums. Annals of Tourism Research. 38(2):403-421.

- Taylor, Christopher and Elisa Perego (2022) ‘Introduction.’ In: Christopher Taylor and Elisa Perego, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Audio Description. London/New York: Routledge, 1-9.

- Van Doorslaer, Luc. (2007): Risking Conceptual Maps: Mapping as a Keywords-Related Tool Underlying the Online Translation Studies Bibliography. Target. 19(2):217-233.

- Walczak, Agnieszka and Fryer, Louise (2017): Creative Description: The Impact of Audio Description Style on Presence in Visually Impaired Audiences. British Journal of Visual Impairment. 35(1):6-17.

List of figures

Figure 1

Accessible comic art

Figure 2

Coma, p. 18 (left), Satin and Tat, n.p. (right)

Figure 3

Threadbare, verso-recto, n.p.

List of tables

Table 1

Comic art selections

Table 2

BPS visitors to The Cartoon Museum