Abstracts

Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine practices in translating adult-oriented linguistic humour in children’s animated movies. The research presents a corpus-based mixed study which draws insights from humour translation, translation of children’s literature (specifically the address problem) and audiovisual translation. The corpus-data were collected from forty randomly chosen Hollywood-made animated movies released between 2010-2019. In order to distinguish a humorous instance as adult-oriented, Akers’ (2013) adult humour categories were applied. The translation strategies applied to the target movies were categorised in accordance with their functions as retainment, replacement and omission. The classification of translation strategies used in this study was developed relying on the available translation strategies of Delabastita (1996) for puns, Leppihalme (1997) for allusions and Mateo (1995) for irony. Further, the data were interpreted both qualitatively, according to Asimakoulas’ (2004) theoretical model for the translation of humour, and quantitatively. The analysis revealed that to preserve adult-oriented humour, the most successful translation strategies belong to the Replacement Set while the least successful set is the Omission Set. According to the overall results, the general tendency is towards the elimination of adult-oriented humour.

Keywords:

- humour translation,

- adult-oriented humour,

- double address,

- translation of children’s literature,

- animated movies

Résumé

L’objectif de cette étude est d’examiner les pratiques des traducteurs dans la traduction de l’humour linguistique orienté vers les adultes dans les films d’animation pour enfants. La recherche présente une étude de corpus s’appuyant sur la recherche dans les domaines de la traduction de l’humour, de la traduction de la littérature jeunesse (en particulier selon le public visé) et de la traduction audiovisuelle. Les données du corpus ont été collectées à partir de quarante films d’animation hollywoodiens choisis au hasard, parus entre 2010 et 2019. Afin de distinguer les instances d’humour pour adultes, on a appliqué les catégories d’Akers (2013) aux données source et cible. On a adapté des stratégies de traduction qui ont été classées selon leurs fonctions respectives de rétention, remplacement et omission. La classification des stratégies de traduction utilisée dans cette étude a été élaborée en s’appuyant sur les stratégies de traduction proposées par Delabastita (1996) pour les jeux de mots, celles de Leppihalme (1997) pour les allusions et sur celles de Mateo (1995) pour l’ironie. En outre, les données ont été interprétées à la fois qualitativement, conformément au modèle théorique d’Asimakoulas (2004), et quantitativement. L’analyse révèle que pour préserver l’humour adulte, les stratégies de traduction les plus efficaces appartiennent au groupe de remplacement, tandis que le groupe le moins efficace est celui des omissions. L’étude démontre plus généralement que la tendance dominante est à l’élimination de l’humour adulte.

Mots-clés :

- traduction de l’humour,

- humour pour adultes,

- double lectorat,

- traduction de la littérature jeunesse,

- films d’animation

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio es examinar las prácticas de traducción del humor lingüístico orientado a los adultos en las películas de animación infantil. La investigación presenta un estudio mixto basado en corpus inspirado por la investigación en los campos de la traducción del humor, la traducción de literatura infantil (en concreto, la cuestión del destinatario) y la traducción audiovisual. Los datos del corpus se recopilaron a partir de cuarenta películas de animación de Hollywood elegidas al azar y estrenadas entre 2010 y 2019. Para distinguir una instancia humorística como orientada a adultos, se aplicaron las categorías de humor adulto de Akers (2013). Las estrategias de traducción aplicadas a las películas de destino se clasificaron de acuerdo con sus funciones de retención, sustitución y omisión. La clasificación de las estrategias de traducción utilizadas en este estudio se desarrolló basándose en las estrategias de traducción disponibles de Delabastita (1996) para los juegos de palabras, Leppihalme (1997) para las alusiones y Mateo (1995) para la ironía. Además, los datos se interpretaron tanto cualitativamente, de acuerdo con el modelo teórico de Asimakoulas (2004) para la traducción del humor, como cuantitativamente. El análisis reveló que, para preservar el humor orientado a los adultos, las estrategias de traducción más exitosas son las de sustitución, mientras que las menos exitosas son las de omisión. Según los resultados globales, la tendencia general es hacia la eliminación del humor orientado a los adultos.

Palabras clave:

- traducción de humor,

- humor para adultos,

- público dual,

- traducción de literatura infantil,

- películas de animación

Article body

1. Introduction

Humour is an essential part of our lives. Whether it is the conversations we have with our friends in our daily lives or shows we watch, humour is everywhere. Especially in the audiovisual field, there are popular works in the humour genre in the form of movies and/or series. One field of humour movies which has existed for years and has been increasingly in demand year after year is Hollywood-made animated movies. Appealing to both children and adults, these movies are big box-office hits. This demand can also be depicted from large production companies, such as Walt Disney Studio Animation, Pixar Animation Studios, DreamWorks Animation, investing larger budgets every year, spending millions of dollars in order to produce animated movies.

Other than the animation, script and dubbing, one of the foremost reasons for a movie’s success is the large audience spectrum of the genre. In the past, adults watched animated movies with the purpose of simply spending time with their children or nostalgically remembering their own childhood; however, over the years, with the broadening of the target age demographics of the movies by some important production companies, animated movies started to attract a more diverse audience in terms of age while continuing to keep young audiences captivated.[1] Adults watching these movies can enjoy the same storyline as children, but the implicit humour added just for their entertainment also attracts them to these movies. A three-decade analysis of the rise of adult-oriented humour in children’s animated movies produced by Hollywood between 1983 and 2012 has shown a five-fold increase in instances of adult-oriented humour since the first 10-year period (Akers 2013: 46).

The popularity of the genre has led to its spread among different countries which has made the translation of these films necessary. For this reason, translation of animated movies, particularly their humorous aspects, has proven to be an important as well as a difficult branch of Translation Studies.

To our knowledge, there have not been any studies examining the translation of adult-oriented humour in animated movies for children. In the case of humour translation in animated movies, cultural and linguistic humour has been examined for different language pairs (to illustrate, De Rosa, Bianchi, et al. 2014; Erguvan 2015; Jabbari and Ravizi 2012; López González 2017; Sadeghpour, Khazaeefar, et al. 2015; Tüfekçioğlu 2013). Overall, the results have revealed that there is a tendency to move towards the target culture.

With this corpus study, we aim to examine translators’ practices while translating adult-oriented linguistic humour in Hollywood animated movies from the source language, English, into Turkish and to determine which of the practices best preserve adult-oriented humour in the target movies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Translating for children

Children’s literature is a broad branch of literature, both with its main audience spectrum starting from toddlers to young adults and with its wide range of material, such as board books, fairy tales, adolescent novels, etc. Likewise, the translation of children’s literature has the same audience spectrum and materials to work with.

One of the features that separate children’s literature from other forms of literature is that children’s literature and, in turn the translation of children’s literature, is written, translated, published, reviewed, read and recommended for children by adults (Ewers 2009). So, writers and translators of children’s literature not only try to appeal to the young audience but also, and probably more so, to the older audience.

Although in principle, the translation of children’s literature is not any different from the translation of other forms of literature, some characteristics of the field call for a separate branch. Alvstad (2010: 22-25) lists these as features of orality, text and image, cultural context adaptation, ideological manipulation (typically, purification) and dual readership.

As mentioned above, children are not the only targeted receivers of children’s literature. So, to have a place in the literary system, writers and translators of the genre have the responsibility of catering to the needs of adults as well as children. This duality is probably the only characteristic that is unique to children’s literature. Shavit summarises this feature as:

The children’s writer is perhaps the only one who is asked to address one particular audience and at the same time to appeal to another […] this demand is both complex and even contradictory by nature […] but one thing is clear: in order for a children’s book to be accepted by adults, it is not enough for it to be accepted by children.

Shavit 1986: 37

While the audience of children’s literature has a wide scope, from toddlers to young adults, some elements of humour, plot, etc. are directed exclusively to adults and cannot (or should not) be understood by children. Therefore, a distinct approach in addressing the reader has emerged in children’s literature and its translation. Wall (1991: 9) points out three different address types for authors of children’s literature as a way of addressing the reader:

-

Single address is when the text is written only for the enjoyment of the children with a disregard for the adult audience.

-

Dual address is when the text is written for both the younger and older audience while keeping both sides at the same level by giving the same message.

-

Double address is when the writer casts the younger reader aside and talks to the adult audience. Egan (1982: 46) describes this type of address as glancing sidelong at the adults listening in the stories and winking. In this kind of situations, the references or the jokes “are not meant to be understood by the younger audience” (Egan 1982: 46). Although this type of address may seem like another ‘single address’ for the adult audience, what constitutes its doubleness is the context. The fact that the text is written primarily for children, but the message is intended for the adult audience, necessitates this second, hence ‘double’ channel.

When faced with challenges such as double or dual address, translators may “use their voices to ‘reduce’ translations” (O’Sullivan 2013: 458). Omission and deletion, substitution, explication and simplification strategies may be used in order to overcome these challenges (Desmet 2007). Wall states that most of the stories for children that have managed to gain a status of classics are those “whose narrators satisfactorily address adults, either as part of a dual audience, or by oscillating between child and adult narratee” (1991: 22) thus, engaging with the adult audience through the double address approach.

Deciding on the intended target reader(s) is an important aspect of translation of children’s literature. In her study, Øster (2006/2014) analyses changes undertaken in the translation of fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen from Danish into English and puts forth that the differences between the source and target texts are a result of the contrasting viewpoint of Andersen and the translator regarding the child reader. In another study, Rudvin and Orlati (2006/2014) investigate the translations of Salman Rushdie’s children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories[2] into Italian and Norwegian in terms of dual readership and conclude that while the Italian translation maintained dual readership, in the Norwegian translation, the translator appeared less constrained by the author’s reputation as a renowned writer and aimed more towards the child reader. Van Coillie and McMartin (2020) also offer various studies on translating for children in different contexts. Specifically, Van Coillie’s (2020) chapter deals with diverse images of child in different cultures and their effects on translation in terms of omissions or alterations. When adult-oriented humour appears in children’s literature, the translator’s task becomes even more challenging since they need to decide to what extent such humour elements should be preserved and/or adopted to the age of the audience and the target culture.

2.2. Translating Humour

Humour, especially verbally expressed humour, has two fundamental characteristics that hinder its travel: cultural and linguistic differences. These limitations lead to some of the most discussed topics in Translation Studies: equivalence and translatability. Such challenges of the translation of humour have attracted scholars within academia since the mid-nineties (to illustrate, Chiaro 2008; 2010a; 2010b; Delabastita 1996; Vandaele 2002).

Since humour is closely related to culture, equivalence cannot be disregarded when it comes to the translation of humour. A distinct approach to the phenomena of equivalence must be taken when humour enters the picture. Chiaro (2010a: 7) explains this divergence in terms of readers’ expectations, using Nida’s distinction of “formal” and “dynamic” equivalence (1964). According to Chiaro (2010a: 7), while recipients of an instruction manual would expect to be given necessary instructions in order to safely use the appliance, in a similar vein, recipients of translated humour would expect to be amused. Therefore, for the translation of verbally expressed humour, formal equivalence is often sacrificed for the sake of dynamic equivalence, that is, so long as the amusement function of the ST is transferred to the TT, the TT may depart from the ST in formal terms (Chiaro 2008: 571). The TT recipients have to be content with exchanges of some features of the ST for a gain in the TL for the sake of functional correspondence.

The aforementioned translational compromises usually concern linguistic barriers which cause humour to be deemed “untranslatable” by some scholars (Burge 1978; Diot 1989). Humour, especially when created with linguistic humour strategies, resists translation. The expectation to be able to create a twin of the ST in the TL would “presuppose the absence of different languages” (Chiaro 2010a: 7). It may be nearly impossible to create the exact pun for the same word with the same meaning between two different languages, so a compromise of sorts is required when dealing with wordplay in interlingual translation.

Another reason for the so-called untranslatability of humour is that translation does not simply represent the substitution of words of one language for those of another language. Humour is as much a cultural phenomenon as a linguistic one and “[a] successful translation does not simply involve the translation of words, but also the translation of worlds” (Chiaro 2008: 587). As a different approach to equivalence for humour, Chiaro (2010a: 10) likens the equivalence level between the ST and TT to a sort of “osmosis,” “a kind of linguistic and cultural give and take which converts the content of the ST into a new form in the TT.” According to Chiaro (2008: 579; 2010a: 10), the possibility of generating humour in the TL is directly proportional to the increase in the area of overlap between the ST and the TT. On this ground, the so-called untranslatability of humour refers, indeed, to the difficulty of achieving the equivalence level necessary for generating amusement in the target recipients.

Additionally, target-culture norms may represent an obstacle for the translator. As every individual has a sense of humour, every culture also has a unique sense of humour. What is amusing for one culture may not be funny, and may even be offensive, for another. It is the translator’s job to find an acceptable translation. Tymoczko (1987) views this notion as the “comic paradigm.” If the “comic paradigm” of the target culture does not coincide with the “comic paradigm” of the source culture, then the humour may not be transferred. According to Vandaele (2010), in cases where there is an incompatibility between the cultures’ sense of humour, ideological, ethical and/or political factors may interfere. Translators may come across humorous instances they find culturally unacceptable and may censor these instances with personal, institutional or political motivations. Unless explicitly stated, the definite cause of an omission of a humorous element is nearly impossible to determine. The reason could be anything from the lack of recognition of the humorous instance to a deliberate translational strategy and/or censorship. While the ethical aspect of these kinds of censorship may be open to debate, with the aforementioned purpose-oriented approach to humour translation, these censorship strategies are not uncommon and may affect the translation of adult-oriented humour in children’s animated movies.

2.3 A General Theory of Verbal Humour and theoretical models for the translation of humour

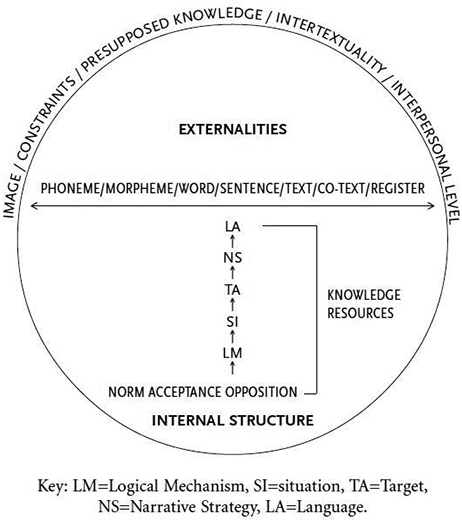

Asimakoulas (2004) adapts Attardo and Raskin’s (1991) General Theory of Verbal Humour (GTVH) to the subtitling of humour with a few additions to the original model. Asimakoulas claims that besides the knowledge resources of language (LA), narrative strategy (NS), target (TA), situation (SI), logical mechanism (LM) and script opposition (SO) put forward by Attardo and Raskin (1991; Attardo 2002), verbal humour also involves social and cognitive expectations which Asimakoulas refers to as “norm acceptance” and “norm opposition” (2004: 824).

Norm acceptance is when something a society has established as funny is used (for example, stereotypes, clichés, etc.). Contrary to incongruity theories of humour, Asimakoulas’ notion of norm acceptance shows that humour can be created without clashes or incongruities, with the help of contextual/social factors that generate socially accepted humour (2004).

Norm opposition operates from the perspective of norms that are deeply rooted in the society. Examples of norm opposition involve situations where there is a clash of some kind (for example, clashing interpretations created with puns, taboo issues, inappropriate situations, etc.). This way, norm opposition may be caused by cognitive (for example, puns) or social (for example, taboo topics) incongruities. Also, deviations from “natural” or “proper” uses of language (for example, stuttering or taking everything literally) are accepted as examples of norm opposition. Verbal humour can simultaneously involve norm acceptance and norm opposition (Asimakoulas 2004: 824).

Asimakoulas also adds contextual variables to GTVH and norm acceptance/opposition. Below, Figure 1 is Asimakoulas’ humour theory model with his additions to GTVH (2004: 825):

Figure 1

Asimakoulas’ humour theory model (2004)

Asimakoulas (2004: 826-827) explains the notion of “externalities” as follows:

-

Image: Some actions, objects, entities that are present on the screen and that affect the perception of humour, and thus, its translation.

-

Constraints: The convenience of creating humour through some words or other textual material (lexical, syntactic ambiguity, spoonerisms, etc.) differs for every language and culture. This externality may also involve the constraints of subtitling and dubbing in terms of translation.

-

Presupposed knowledge: The encyclopaedic knowledge accumulated by experience or cultural assumptions that the receivers possess individually or collectively as a society. The term contains both linguistic and cultural knowledge. This externality can be applied to adult-oriented humour in works aimed for children.

-

Intertextuality: Texts that depend on previously known texts. Allusions, parodies or repeated segments can work as means for humorous intertextuality.

-

Interpersonal level: The expression of an attitude or a feeling that acts in accordance with forms of superiority/disparagement humour. The humour can get personal either with the purpose of being hurtful towards someone or a group of people or not. If making this kind of humorous comments in a given context is unacceptable, a norm opposition is created. If it is a recurring humorous device, then norm acceptance occurs through this norm opposition.

We applied Asimakoulas’ theoretical model for the translation of humour to the analysis of the corpus data of forty movies and compared the STs and TTs in terms of the preservation of adult-oriented humour. In this article, the criteria for success[3] is established as the transfer of linguistic properties of the humorous elements according to Asimakoulas’ humour theory model (2004).

3. Research questions and methods

3.1 Research questions

The paper aims to find the answers to the following questions:

-

What are the tendencies of translators in the translation of adult-oriented humour in children’s animated movies?

-

Which strategies are best in preserving adult-oriented humour in children’s animated movies?

To answer these questions, the following procedures have been pursued.

3.2 Data collection

The corpus data for this study consist of humorous scenes in child-oriented animated movies that cater to the adult audience’s amusement. To create the corpus, forty movies were chosen randomly from the available 144 released from different companies, such as Walt Disney Studio Animation, Pixar Animation Studios, etc. between 2010 and 2019. The corpus was constructed with the use of a free service website[4] created for generating random numbers.

The instances of linguistic adult-oriented humour (Raphaelson-West 1989) in the source movies were compared with their dubbed versions in the translated movies (or target movies). The passages in both source and target movies were filtered according to Akers’ (2013: 31-32) adult humour categories as follows:

-

Adult Appropriate References: When a humorous instance refers to a situation, person or thing that only an adult should understand.

-

Vocabulary: When a type of vocabulary that is often inaccessible to children because of its level of difficulty is used.

-

Intertextual Dialogue: When a humorous instance includes a reference to another movie or a literary work, etc.

-

Sexual Innuendo: When a humorous instance is realised through allusions and references to sexuality.

-

Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords: When unusual terms or methods are used with the aim of hiding or replacing swearwords.

To identify the forms of linguistic verbal humour used in the source and target movies, we have taken Norrick (1994; 2004) and Dynel’s (2009) classifications of linguistic verbal humour strategies (punning, hyperbole, comparison, paradox, spoonerism, irony, sarcasm, allusion, euphemism) as a basis.

For triangulation, three different researchers were requested to watch the movies and identify the items of linguistic adult-oriented humour. Further, the items were discussed and identified in agreement.

3.3 Data Analysis

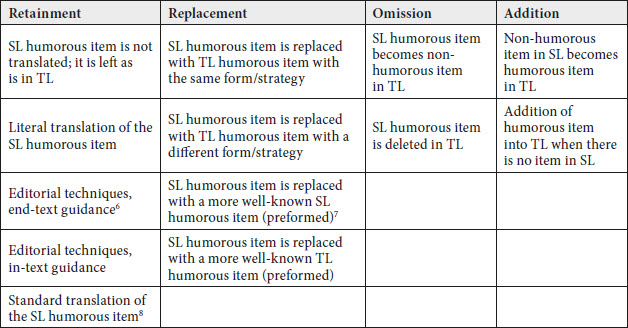

We developed the classification of humour translation strategy sets relying on the available translation strategies of Delabastita (1996) for puns, Leppihalme (1997) for allusions and Mateo (1995) for irony.

These strategies were grouped according to their functions under four translation strategy sets: 1) Retainment, 2) Replacement, 3) Omission and 4) Addition.[5]

Retainment strategies cause minimum change in the meaning of the source item while Replacement strategies change the meaning through replacing the humorous item with other items from the TL. On the other hand, while Omission strategies either delete or change humorous items of the ST in a way that causes the elimination of humour, Addition strategies may be used to create humour in the TT where there is no such item in the ST. This may also occur as a form of compensation.

Below, Table 1 shows the translation strategies gathered under the abovementioned sets:

Table 1

Additionally, we used Asimakoulas’ (2004) humour theory model to analyse the data qualitatively in terms of norm acceptance/opposition and externalities.

4. Findings

4.1 Research question 1

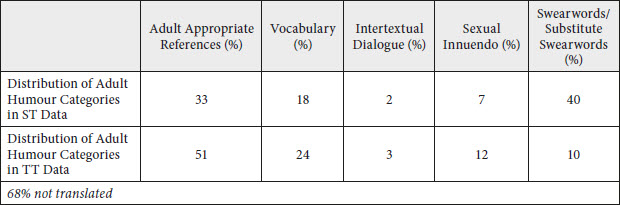

The analysis of forty movies yielded 392 instances of linguistic adult-oriented humour. When these instances were identified as one of the five pre-determined categories of adult-oriented humour, it was found that 40% of the instances belonged to Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords, 33% belonged to Adult Appropriate References and 18% belonged to Vocabulary with Sexual Innuendo and Intertextual Dialogue at 7% and 2% respectively. The TT corpus analysis revealed that 127 (32%) of the 392 instances of linguistic adult-oriented humour were preserved in the TT. Out of the 127 translated instances, 51% belonged to Adult Appropriate References, 24% belonged to Vocabulary and 12% belonged to Sexual Innuendo with Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords and Intertextual Dialogue, with 10% and 3% respectively. The distribution is shown in Table 2. It appears that Intertextual Dialogue is the most preserved adult humour category with 1% loss, closely followed by Sexual Innuendo with 2% loss. Vocabulary follows them with 10% loss, while 19% of the Adult Appropriate References was lost in translation. Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords has the largest loss by far, with 36%. As a result, 68% of the total adult humour categories were not translated as adult humour instances in the target movies.

Table 2

Distribution of adult humour categories

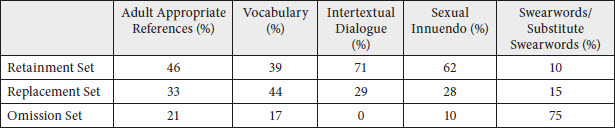

After determining the distribution of adult humour categories, we gathered the instances under the three translation strategy sets (Retainment, Replacement, Omission) according to their translations into Turkish. According to the results obtained, Retainment was the most widely used set for Adult Appropriate References (46%), Intertextual Dialogue (71%) and Sexual Innuendo (62%). Replacement came first for Vocabulary (44%) while for Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords (75%), the Omission set was preferred the most by translators. The distribution of translators’ tendencies according to the various translation strategy sets is shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Distribution of translators’ tendencies for translation strategy sets

Examples for the most used sets for each category are given below.

In Example 1, when Bogo says that he needs to acknowledge the elephant in the room with a serious expression, the scene creates an expectation on the audience that there is a major problem that they have to discuss. However, when Bogo nods to Francine, who is an elephant, and wishes her a happy birthday, the literal meaning of the phrase is realised. This shift from expectation to reality is formed through a pun on the figurative and literal meaning of the phrase the elephant in the room. The scene is adult-oriented because of the cognitive incongruity caused by the pun and the presupposed vocabulary knowledge of the phrase. The fact that linguistic humour is achieved through humorous communication between the screenwriter and the audience also makes the scene adult-oriented since this type of humorous communication is covert and requires the audience to be aware of humorous instances that are outside the plot of the movie. In the TT, the scene is translated via a translation strategy from the Retainment Set. When translated literally, the pun is lost in translation due to linguistic differences between the source and target languages. As a result, the element of linguistic adult-oriented humour is lost.

In Example 2, the source of linguistic adult-oriented humour of the scene is Floyd’s description of Gru’s baldness. In the scene, the term follically challenged is a euphemism for bald. A cognitive incongruity is created with this euphemism. Moreover, to understand the meaning of the euphemism, the audience has to have the required vocabulary knowledge. Also, the fact that being bald is not a bad thing as such, and that Floyd uses a euphemism instead of the word bald produces an instance of disparaging humour, with Gru being the target of the joke. This disparagement forms a social incongruity as making fun of someone’s insecurity in public is not a socially acceptable behaviour. These cognitive and social incongruities result in the norm opposition which constitute the linguistic adult-oriented humour instance of the scene. In the TT, the translator used a strategy from the Replacement Set to translate the instance of linguistic adult-oriented humour. With the translation, saç açısından sorunları olan biri [a person with hair problems], the euphemism is preserved in the TT; however, the required vocabulary knowledge and the level of disdain are reduced to those of a general audience. As a result, although linguistic humour is preserved for the general audience, the elements of adult-oriented humour are lost in translation.

In Example 3, in response to Buttercup’s suggestion, Hamm requests the famous Shakespeare play Hamlet. This scene has two aspects that make it a humorous one: The first aspect is the pun on Hamm and Hamlet. In an indirect way, Hamm wants to get in the show and displays his desire with a pun. The second aspect is the allusion to Shakespeare. This presupposed knowledge of theatre and the intertextuality make the humorous scene adult-oriented. Since Shakespeare is a universally known literary figure and the musical Hamlet has the same title in the TL, the musical’s name is left the same in the TT with a Retainment Set strategy without any attempt at domestication, which in turn keeps the original ST meaning and addressee.

In Example 4, the characters are looking around and Fear thinks he saw a bear. When Disgust says that there are no bears in San Francisco, Anger responds by saying that he just saw a really hairy guy that looked like a bear. In the scene, Anger’s answer represents a form of norm opposition as a result of both cognitive and social incongruities. The cognitive incongruity is created with the pun on the word bear which means both an animal and “a gay or bisexual man with a burly physique and a large amount of body hair”[14] while the social incongruity is a result of having the taboo topic of sexuality alluded to in a children’s movie. Also, vocabulary knowledge is necessary to understand the pun, which is more likely for the adult audience to possess. In the TT, the instance of linguistic adult-oriented humour is translated with a strategy from the Retainment Set. However, as there is no sexual connotation for the word ayı [bear] in the TL, the pun and the sexual innuendo are eliminated in the TT. Only the (disparaging) humour of comparing a hairy man to a bear is present in the TT.

In Example 5, Sid is floating on an ice floe when a huge crab suddenly appears. His exclamation of Holy crab is a euphemism created through a pun on crap – crab. While the pun results in the cognitive incongruity, the use of euphemism in a children’s movie creates a form of social incongruity through a register clash. These forms of norm opposition designate the addressee of the ST scene as adults. In the TT, the scene is translated with a Replacement Set strategy. The euphemised exclamation Holy crap is replaced with another exclamation from the TL that is widely used in children’s movies, hay bin kunduz [a thousand beavers], which has been modified as hay bin yengeç [a thousand crabs] to fit in the scene. Even though the TL version of the exclamation still has an underlying meaning of damnation, it is a euphemism used, especially in children’s movies, for this purpose. As a result, although the element of adult-oriented humour is lost in translation, a general sense of humour is preserved in the TT.

4.2 Research question 2

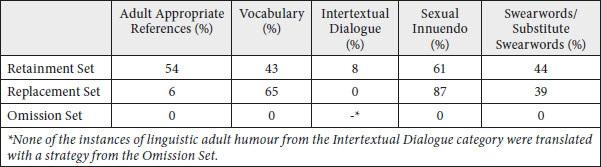

It appears that some instances lost their adult-oriented humour properties and turned into instances of either general humour (20%) with single or dual addresses or no humour at all (48%). It is also apparent that in some of the instances in which the elements of adult-oriented humour were preserved, there was a shift in adult humour categories and/or humour types, namely from linguistic to cultural or universal humour. In line with the aim of the study, the strategy sets that preserved adult-oriented humour the most for each category of adult humour are shown in Table 4. Replacement was the most successful set for Adult Appropriate References, Vocabulary and Sexual Innuendo categories while Retainment was the most successful set for Intertextual Dialogue and Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords categories. Omission was the least successful set for all of the adult-oriented humour categories.

Table 4

Strategy sets for preserving adult-oriented humour

Examples for the most successful sets in preserving adult-oriented humour for each category are given below.

In Example 6, when Finn introduces himself, he only says “British Intelligence” without specifying that he works for them and Mater misunderstands the word intelligence. Instead of the intelligence agency, Mater thinks Finn is referring to his IQ and answers in accordance with that. The linguistic adult humour of the scene comes from the cognitive incongruity created with the pun on the word intelligence, the presupposed knowledge of British Intelligence and the irony of Mater evaluating his intelligence level as average while demonstrating his silliness with this misunderstanding. In the TT, the humorous instance is translated via a Replacement strategy. The pun is replaced with another pun from the TL, haber alma – haber almak [gathering information – receiving news]. As a result, with this replacement, the linguistic adult-oriented humour is transferred to the TT as a pun like the ST linguistic adult-oriented humour instance while the irony is lost.

In Example 7, Wayne’s joke is constructed on a pun on the word litter, which means both trash and “a number of young animals born to an animal at one time.”[18] The presupposed vocabulary knowledge of the two meanings of the word and the cognitive incongruity of the pun create adult-oriented humour. In the TT, the adult-oriented humour is preserved through another pun via a Replacement Set strategy. Although the pun is again on the word group that describes the pack of wolves (it sürüsü), in the TL the meaning is different than the SL version. The definition of it sürüsü changes with the context, the literal meaning of the word group is a pack of dogs, while the idiom version is an insult that means a group of contemptible people. As a result, although the presupposed vocabulary knowledge and the norm opposition created through the pun are kept in the TT, the adult-oriented humour category is changed from Vocabulary to Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords because of the use of an insult in a child-oriented movie.

In Example 8, Open Sesabees is an allusion to the famous quotation “Open Sesame” from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.[20] The pun on bees creates a cognitive incongruity and the intertextuality of the scene requires a knowledge of the original quotation. This norm opposition and presupposed knowledge cause the scene to be adult-oriented. In the TT, the humorous instance is translated with a Retainment Set strategy. With this translation strategy, the quotation is translated with the standard translation of the quotation in the TL, which is “Açıl susam açıl” [Open sesame open], with a wordplay similar to the ST pun, “Açıl kovan açıl” [Open hive open]. Therefore, although the ST pun is lost in translation, the allusion to Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves is preserved with an added allusion to bees. As a result, the aspect of linguistic adult-oriented humour is preserved in the TT.

In Example 9, a panda kid points to the top of Mr. Ping’s body and goes gradually lower while asking questions. When he asks, “What’s that?” and gestures to somewhere below the frame, which happens to be Mr. Ping’s groin area, the sequence sets up idea that the response will be of a sexual nature. Additionally, Mr. Ping responds to the kid’s question by holding out a bowl of dumplings that was hidden until then and says, “My dumplings.” In the context of the scene, this is a euphemism for male genitalia. While the sexual innuendo of the sequence causes social incongruity because it is a taboo subject for a children’s movie, the anticipation and the euphemism constitute cognitive incongruity. When all of these are considered, the scene is an example of linguistic adult-oriented humour. In the TT, the scene is translated with a Replacement strategy. Since dumplings are not well-known in the target culture, the dish is replaced with one from the target culture which can transfer the euphemism into the TT. As a result of this translation, the TT maintains both the adult humour category and the linguistic adult-oriented humour.

In Example 10, Eret’s warning exclamation of “Duck” acts like a censor to Astrid’s rude language in the scene. While this euphemism formed with the censorship creates a cognitive incongruity, the taboo of having coarse language in a children’s movie creates a social incongruity. Because of these forms of norm opposition, the scene becomes a linguistic adult-oriented humour instance. In the TT, the instance is translated with a Retainment strategy. With this translation strategy, while Astrid’s words are translated literally, the incomplete sentence and the element of censorship is preserved. The reason for this successful transfer is the expectation of a curse word the scene provokes in the audience, which is achieved through the intonation and visuals as well as the script. Therefore, for this scene, the external restrictions have become external aids for the translator. As a result, the linguistic adult-oriented humour is preserved in the TT. However, the only reason that the taboo word is preserved is that it is not expressed explicitly in the ST but implied and it can be understood from the context. Basically, the translator did not preserve the taboo word but preserved the context.

The findings revealed that Replacement Set is the most successful set in preserving both adult-oriented humour and humour in general. This may be due to the fundamental motto of humour translation: the sacrifice of formal equivalence for the sake of dynamic equivalence in order to transfer the amusement function of the ST to the TT (Chiaro 2008: 571). With the strategies from the Replacement Set, even if the adult-oriented humour is not preserved, either deliberately or involuntarily, the translators have made an effort to keep the humorous effect for the entertainment of the target audience. Although Retainment Set strategies are not as successful as Replacement Set strategies, Retainment Set is nevertheless successful in preserving adult-oriented humour.

The findings also revealed that the general tendency for the translation of adult-oriented humour is to eliminate the humour altogether; this tendency is mostly centred around the Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords category. Moreover, Omission is the most applied and also the least successful among all sets for preserving not only the elements of adult-oriented humour but of general humour too. The correlation between the two data sets would suggest that the increased preference for Omission strategies led to a decline in the preservation of adult-oriented humour and general humour.

There could be several reasons behind the preferences of the translators that could be valid for the elimination of humour for all categories of adult humour. These reasons may be:

-

Censorship: Censorship may be carried out by translators themselves, the target movie’s production company and/or the authorities responsible. Zabalbeascoa states that in most cases translators do not have the last word on their work and in order to make “radical departures” from the original they need “permission” from an authority (1996: 249). If the humorous instance is in contrast with the values of the authorities and/or society, the translational behaviour is shaped accordingly (Toury 1995). The elimination of humour for adult-oriented humorous instances under the adult humour categories Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords and Sexual Innuendo supports this reason, especially the tendency of the translators to use translation strategies from the Omission Set demonstrates as an example of censorship.

-

Movie Ratings: Movies are rated according to the Motion Picture Association’s (MPA) rating system. The MPA’s rating guide divides movies into five ratings. These ratings are G (General Audiences), PG (Parental Guidance Suggested), PG-13 (Parents Strongly Cautioned), R (Restricted) and NC-17 (No One 17 and Under Admitted).[23] The first three ratings, G, PG and PG-13, are suitable for children; however, the higher the rating is, the narrower the audience spectrum gets. Also, the fact that the rating of the movies is determined by the country the movies are released in puts pressure on the translators to keep the movies’ ratings low enough for children. According to Article 10 of the Regulation on the Procedures and Principles Regarding the Evaluation and Classification of Motion Picture Films (Sinema Filmlerinin Değerlendirilmesi ve Sınıflandırılmasına İlişkin Usul ve Esaslar Hakkında Yönetmelik) by The Republic of Türkiye’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism[24], movies and trailers that are to be released for circulation are evaluated and classified by taking into consideration behaviours that may set negative examples, such as sexuality, nudity, violence, drugs, rude and slang language. The ambiguity of what is considered a negative example may push the translators and/or the target movies’ production companies into being on the safe side by eliminating adult-oriented humour from children’s movies because even getting a PG-13 rating may pose a problem because of the decline in possible audience numbers, which is an unwanted situation when box office ratings are at stake. This reason for eliminating adult-oriented humour may be valid for adult humour categories such as Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords and Sexual Innuendo.

-

Parents’ Preferences: Likewise, and also as a result of the previous reasons, parents’ opinions about which movies are appropriate for their children may affect the norms for translating child-oriented animated movies. As stated earlier, works for children are written, translated, published, purchased, read/watched and recommended by adults for children. So, writers and translators of animated movies for children are not only trying to appeal to their young audience but also to older members of the audience as these adults are the ones who are going to allow their children to see these movies. Parents are not very keen on letting their children watch movies with restricted ratings. This preference can be observed in websites set up for movie reviewing, especially for parental guidance.[25] Naturally, parents’ preferences affect the translation process of adult-oriented humour in children’s movies. The elimination of adult-oriented humour under the categories of Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords and Sexual Innuendo corresponds to this reason.

-

Linguistic Barriers: Another factor could consist in the linguistic issues that translators encounter during the translation process. Since humorous instances are formed through linguistic strategies, such as puns, spoonerisms, allusions, etc., humour is dependent on the linguistic properties of the language. In order to keep the humorous effect, the TT should either have the same or at least similar linguistic features or the translators should make an effort to keep the adult-oriented humour with a creative translation. If the latter is the case, the translation indicates that the elements of adult-oriented humour is preserved in the TT with the purpose of entertaining the adult audience. Since the corpus-data for this study is comprised of linguistic humour, linguistic barriers are a possible reason as a hindrance to humour transfer.

-

Translator’s Incompetence: The competence of the translator is important for every type of translation; however, it is of the upmost importance when it comes to humour translation. As Vandaele (2010) explains, the translator’s sense of humour could be insufficient to recognise the humour, or they could recognise it, but may not find the instance entertaining and laughable. Moreover, they could recognise the humour and find the instance entertaining but may be unable to create it in the TT. In all of these cases, the result would be the elimination of humour, which means that the TT does not fulfil its function. This reason for the elimination of humour may be valid for all humorous instances for all adult humour categories.

-

Poor Working Conditions: Working conditions are also of great essence for the translator’s performance. Time pressure and poor salary may undoubtedly affect any person’s efficiency, especially in the big-buck economy of blockbuster movies. Within the context of humour translation, a lack of time and motivation may indicate less time afforded or spent on the search for more creative solutions.

As analysing the reasons for failure to preserve adult-oriented humour is beyond the scope of this paper; a study focusing on the aforementioned reasons could put forward better-grounded reasons.

To compare our findings with the studies focusing on the translation of double/dual address, as well as cultural and linguistic elements in humour, overall, our study has also demonstrated that there is a tendency to move towards the target culture in order to produce (adult-oriented) humour which makes the text more target-audience friendly.

5. Conclusion

This research aimed to examine translators’ practices while translating linguistic adult-oriented humour in child-oriented animated movies through a corpus analysis of adult-oriented humour in forty Hollywood-made animated movies released between the years of 2010-2019 and translated into Turkish. It also aimed to determine translation trends and the specific practices used to preserve adult-oriented humour in the translated movies. In order to distinguish the various forms of linguistic adult-oriented humour, we applied Akers’ (2013) adult humour categories and Norrick (1994; 2004) and Dynel’s (2009) classifications of linguistic verbal humour. The results revealed that while Intertextual Dialogue is the most translated adult humour category, Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords is the least used category.

The results also revealed that Retainment Set strategies are most commonly used for Adult Appropriate References, Intertextual Dialogue and Sexual Innuendo, while Replacement Set is the most applied strategy for issues of Vocabulary. For Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords, the most commonly used strategies correspond to the Omission Set. Further, Replacement Set strategies are the most successful strategies in preserving adult-oriented humour for Adult Appropriate References, Vocabulary and Sexual Innuendo, while Retainment is the most successful set in preserving adult-oriented humour for Intertextual Dialogue and Swearwords/Substitute Swearwords.

According to our findings, the general trend is towards the elimination of adult-oriented humour. There could be several factors explaning this tendency such as the influence of censorship, movie ratings, parents’ concerns, linguistic differences, the incompetence of translators and poor working conditions.

The fact that the corpus-data were collected from forty movies constitutes a limitation for the study. Further research may focus on the translation of linguistic, cultural and universal (Raphaelson-West 1989) adult-oriented humour in a larger corpus of children’s animated movies.

Appendices

Notes

-

[*]

This article is part of an unpublished, freely accessible MA Thesis “Translation of Adult-Oriented Humour in Children’s Animated Movies: A Corpus-Based Study” written by Gulce Naz Semi, supervised by Prof. Dr. Elena Antonova-Unlu. Consulted on 21 July 2024, https://openaccess.hacettepe.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/11655/25757.

-

[**]

Department of Translation and Interpreting

-

[***]

Department of Foreign Language Education

-

[1]

McKay, Hollie (2016): Is Hollywood ruining children’s movies with adult-focused content?. Fox News. 08 April 2016.

-

[2]

Rushdıe, Salman (1990): Haroun and the Sea of Stories. New York: Penguin.

-

[3]

In this article, the terms “success” and “successful” solely include the transfer of linguistic properties that produce humour in a text. Neither the level of entertainment of the audience nor the commercial success of the target movies are included in the criteria.

-

[4]

Urbaniak, Geoffrey, Plous, Scott (2013): Research Randomizer (Version 4.0). Consulted on 7 January 2020, <http://www.randomizer.org/>.

-

[5]

Translation strategies from the Addition Set will not be applied in the analysis of this article; however, it is included for the entirety of the table and for future research.

-

[6]

“Editorial techniques, end-text guidance” translation strategy from the Retainment Set will not be included in the analysis since the corpus-data consist of audiovisual material.

-

[7]

In these strategies “preformed” refers to an already established item which is different than the SL item mentioned the ST.

-

[8]

“Standard translation of the SL humorous item” refers to the established translation of the item in the TL. “Literal translation of the SL humorous item” and “Standard translation of the SL humorous item” translation strategies may correspond to the same SL item.

-

[9]

Bush, Jared, Howard, Byron, Moore, Rich (2016): Zootopia. Walt Disney Animation Studios.

-

[10]

All back translations belong to the authors and are checked by a professional translator.

-

[11]

Coffın, Pierre, Renaud, Chris (2013): Despicable Me 2. Illumination Entertainment; Universal Pictures.

-

[12]

Unkrıch, Lee (2006): Toy Story 3. Pixar Animation Studios; Walt Disney Pictures.

-

[13]

Del Carmen, Ronnie, Docter, Pete (2015): Inside Out. Pixar Animation Studios; Walt Disney Pictures.

-

[14]

Lexico.com (2022): bear. Oxford University Press. <https://www.lexico.com/definition/bear>.

-

[15]

Martıno, Steve, Thurmeier, Michael (2012): Ice Age: Continental Drift. Blue Sky Studios; Twentieth Century Fox Animation.

-

[16]

Lasseter, John, Lewis, Bradford (2011): Cars 2. Pixar Animation Studios; Walt Disney Pictures.

-

[17]

Tartakovsky, Genndy (2015): Hotel Transylvania 2. Pixar Animation Studios; Walt Disney Pictures.

-

[18]

Lexico.com (2022): litter. Oxford University Press. <https://www.lexico.com/definition/litter>.

-

[19]

Johnston, Phil, Moore, Rich (2018): Ralph Breaks the Internet. Walt Disney Animation Studios.

-

[20]

Galland, Antoine (1704/1884): Les Mille & Une Nuit: Contes Arabes. (Translated from the French by Richard Francis Burton) London: Kamashastra Society.

-

[21]

Carlonı, Alessandro and Nelson, Jennifer Yuh (2016): Kung Fu Panda 3.

-

[22]

DeBlois, Dean, (2014): How to Train Your Dragon 2. DreamWorks Animation.

-

[23]

Motion Picture Association, Inc (1986): Filmratings.com: The Classification & Rating Administration. Consulted on 07 July 2021, <https://www.filmratings.com>.

-

[24]

T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Mevzuat Bilgi Sistemi (2019): Sinema Filmlerinin Değerlendirilmesi ve Sınıflandırılmasına İlişkin Usul ve Esaslar Hakkında Yönetmelik. Consulted on 07 July 2021, <https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=33906&MevzuatTur=7&MevzuatTertip=5>.

-

[25]

Çocukla Sinema (2019): Çocukla Sinema. Consulted on 07 July 2021, <https://www.cocuklasinema.com/>.

Common Sense Media (2003): Common sense media. Consulted on 07 July 2021, <https://www.commonsensemedia.org/>.

Parent Previews (2013): Parent Previews. Consulted on 07 July 2021, <https://parentpreviews.com/>.

Bibliography

- Akers, Chelsie Lynn (2013): The Rise of Humor: Hollywood Increases Adult Centered Humor in Animated Children’s Films Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Utah: Brigham Young University.

- Alvstad, Cecilia (2010): Children’s literature and translation. In: Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies. Amsterdam, Philadephia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 1, 22-27.

- Asimakoulas, Dimitris (2004): Towards a Model of Describing Humour Translation. Meta. 49(4):822-842.

- Attardo, Salvatore (2002): Translation and Humour. The Translator. 8(2):173-194.

- Attardo, Salvatore and Raskin, Victor (1991): Script theory revis(it)ed: joke similarity and joke representation model. Humor-International Journal of Humor Research. 4(3-4). 10.1515/humr.1991.4.3-4.293

- Burge, Tyler (1978): Self-Reference and Translation. In: Franz Guenthner and Monica Guenthner-Reutter, eds. Meaning and Translation: Philosophical and Linguistic Approaches. London: Duckworth, 137-153.

- Chiaro, Delia (2008): Verbally expressed humor and translationessed humor and translation. In: Victor Raskin, ed. The Primer of Humor Research. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 569-608.

- Chiaro, Delia, ed. (2010a): Translation and Humour: Translation, Humour and Literature. Bloomsbury Publishing vol. 1.

- Chiaro, Delia, ed. (2010b): Translation, Humour and the Media. Bloomsbury Publishing vol. 2.

- Delabastita, Dirk (1996): Introduction. The Translator. 2(2):127-139.

- De Rosa, Gian Luigi, Bianchi, Francesca, De Laurentiis, Antonella and Perego, Elisa, eds. (2014): Translating Humour in Audiovisual Texts. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Desmet, Mieke K. T. (2007): Babysitting the Reader: Translating English Narrative Fiction for Girls into Dutch (1946-1995). Bern: Peter Lang.

- Diot, Roland (1989): Humor for Intellectuals: Can it Be Exported and Translated? Meta. 34(1):84-87.

- Dynel, Marta (2009): Beyond a Joke: Types of Conversational Humour. Language and Linguistics Compass. 3(5):1284-1299.

- Egan, Michael (1982): The Neverland of Id: Barrie, Peter Pan, and Freud. Children’s Literature. 10(1):37-55.

- Erguvan, Mehmet (2015): Relevance-Theoretic Approach to the Turkish Translation of Humorous Culture-Specific Items in Family Guy Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Ankara: Hacettepe University.

- Ewers, Hans-Heino (2009): Fundamental Concepts of Children’s Literature Research: Literary and Sociological Approaches. London: Routledge.

- Jabbari, Ali Akbar and Ravizi, Nikkhah Z. (2012): Dubbing Verbally Expressed Humor: An Analysis of American Animations in Persian Context. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2(5):263-270.

- Leppihalme, Ritva (1997): Culture Bumps: An Empirical Approach to the Translation of Allusions. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- López González, Rebeca Cristina (2017): Humorous Elements and Translation in Animated Feature Films: Dreamworks (2001-2012). Monografias de Traduccion e Interpretacion (MonTI). 2017(9):279-305.

- Mateo, Marta (1995): The Translation of Irony. Meta. 40(1):171-178.

- Nida, Eugene Albert (1964): Toward a Science of Translating. E.J. Brill.

- Norrick, Neal R. (1994): Involvement and joking in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics. 22(3-4):409-430.

- Norrick, Neal R. (2004): Non-verbal humor and joke performance. Humor-International Journal of Humor Research. 17(4):401-409.

- Øster, Anette (2006): Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales in Translation. In: Jan Van Coillie and Walter P. Verschueren, eds. Children’s Literature in Translation: Challenges and Strategies. London and New York: Routledge, 141-155.

- O’Sullivan, Emer (2013): Children’s literature and translation studies. In: Carmen Millán and Francesca Bartrina, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies. London: Routledge, 451-463.

- Raphaelson-West, Debra S. (1989): On the Feasibility and Strategies of Translating Humour. Meta. 34(1):128-141.

- Rudvin, Mette and Orlati, Francesca (2006): Dual Readership and Hidden Subtexts in Children’s Literature. In: Jan Van Coillie and Walter P. Verschueren, eds. Children’s Literature in Translation: Challenges and Strategies. London and New York: Routledge, 157-184.

- Sadeghpour, Hamid Reza, Khazaeefar, Ali and Khoshsaligheh, Masood (2015): Exploring the Rendition of Humor in Dubbed English Comedy Animations into Persian. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature. 4(6):69-77.

- Shavit, Zohar (1986): Poetics of Children’s Literature. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies – and beyond. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Tüfekçioğlu, Özlem (2013): Görsel-İşitsel Metinlerin Çevirisinde Mizah Unsurlarının Çevirisi: “Ice Age” Serisi ve Çevirilerinin İncelenmesi Unpublished Master’s Thesis. İstanbul: İstanbul University.

- Tymoczko, Maria (1987): Translating the Humour in Early Irish Hero Tales: A Polysystems Approach. New Comparison. 3:83-103.

- Van Coillie, Jan (2020): Diversity can change the world: Children’s literature, translation and images of childhood. In: Jan Van Coillie and Jack McMartin, eds. Children’s Literature in Translation: Texts and Contexts. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 141-156.

- Van Coillie, Jan and McMartin, Jack, eds. (2020): Children’s Literature in Translation: Texts and Contexts. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Vandaele, Jeroen, ed. (2002): Translating Humour. The Translator. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing 2nd ed., vol. 8.

- Vandaele, Jeroen (2010): Humor in translation. In: Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 1, 147-152.

- Wall, Barbara (1991): The Narrator’s Voice: The Dilemma of Children’s Fiction. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zabalbeascoa, Patrick (1996): Translating Jokes for Dubbed Television Situation Comedies. The Translator. 2(2):235-257.

List of figures

Figure 1

Asimakoulas’ humour theory model (2004)

List of tables

Table 1

Table 2

Distribution of adult humour categories

Table 3

Distribution of translators’ tendencies for translation strategy sets

Table 4

Strategy sets for preserving adult-oriented humour