Abstracts

Abstract

This article deals with the ethics of intralingual translation and cultural accessibility. Based on the analysis of five characteristic text examples of the Volxbibel, a German intralingual translation of the Bible which makes excessive use of local adaptive strategies and whose central aim is to make the Scriptures accessible to youngsters, it will be shown that cultural accessibility can only be achieved if the ethical dimension of semiotic translational transfer is taken duly into account. Methodologically, the analysis will be based on a contrastive pragmatic analysis of the Volxbibel and its canonical counterpart, the Lutherbibel. The results of the analysis reveal that ethically grounded intralingual translation can only be achieved when transfer actions are oriented, not only towards the translational skopos and the target-text, but, at the same time, respect the source-text author’s intention(s) and the source-text’s ideological and socio-cultural background. Finally, on the grounds of these results, a slight adjustment of Zethsen’s and Hill-Madsen’s criterial definition of translation is proposed, by explicitly integrating therein the ethical dimension. This would contribute to a more precise delineation of both intralingual and interlingual translation.

Keywords:

- synchronic intralingual translation,

- Bible for special target groups,

- cultural accessibility,

- ethical dimension,

- criterial definition

Résumé

Cet article traite de l’éthique de la traduction intralinguistique et de l’accessibilité culturelle. Sur la base de l’analyse de cinq exemples de textes caractéristiques du Volxbibel, une traduction allemande intralinguistique de la Bible qui fait un usage excessif des stratégies d’adaptation locales et dont le but central est de rendre les Écritures accessibles aux jeunes, il sera montré que l’accessibilité culturelle ne peut être atteinte que si la dimension éthique du transfert sémiotique traductionnel est dûment prise en compte. Méthodologiquement, l’analyse s’appuiera sur une analyse pragmatique contrastive de la Volxbibel et de son pendant canonique, la Lutherbibel. Les résultats de l’analyse révèlent qu’une traduction intralinguistique fondée sur l’éthique ne peut être réalisée que lorsque les actions de transfert sont non seulement orientées vers le skopos traductionnel et le texte cible, mais, en même temps, qu’elles respectent l’intention ou les intentions de l’auteur du texte source et le contexte idéologique et socioculturel du texte. Enfin, sur la base de ces résultats, un léger ajustement de la définition critérielle de la traduction de Zethsen et Hill-Madsen est proposé, en y intégrant explicitement la dimension éthique. Cela contribuerait à une délimitation plus précise de la traduction intralinguistique et interlinguistique.

Mots-clés :

- traduction intralinguistique synchronique,

- la Bible pour groupes cibles particuliers,

- accessibilité culturelle,

- dimension éthique,

- définition critérielle

Resumen

Este artículo trata de la ética de la traducción intralingüe y la accesibilidad cultural. A partir del análisis de cinco ejemplos textuales característicos del Volxbibel, una traducción intralingüe alemana de la Biblia que hace un uso excesivo de estrategias adaptativas locales y cuyo objetivo central es hacer la Palabra Sagrada asequible a los jóvenes, se demostrará que la accesibilidad cultural sólo puede lograrse si se tiene debidamente en cuenta la dimensión ética de la transferencia semiótica traduccional. Metodológicamente, el análisis se basará en un análisis pragmático contrastivo del Volxbibel y de su homólogo canónico, el Lutherbibel. Los resultados del análisis revelan que la traducción intralingüe con fundamento ético sólo puede lograrse cuando las acciones de transferencia se orientan no sólo hacia el skopos traduccional y el texto meta, sino que, al mismo tiempo, respetan la(s) intención(es) del autor del texto fuente y el trasfondo ideológico y sociocultural del texto fuente. Por último, sobre la base de estos resultados, se propone un ligero ajuste de la definición criterial de la traducción de Zethsen y Hill-Madsen, integrando explícitamente en ella la dimensión ética. Ello contribuiría a una delimitación más precisa tanto de la traducción intralingüística como de la interlingüística.

Palabras clave:

- traducción intralingüe sincrónica,

- Biblia para grupos destinatarios especiales,

- accesibilidad cultural,

- dimensión ética,

- definición criterial

Article body

1. Introduction

In recent years, the translation of the Bible for special target groups has known an unprecedented boom worldwide. Though many of these translations are interlingual ones, there is, however, also a great amount of intralingual translation of the Scriptures for children and youngsters.[1] Motives and reasons that have elicited this astonishing increase may, of course, vary. It may be due to the efforts of religious institutions or of single individuals to counteract an all too visible decline in faith among the younger members of society; or it may even be motivated by sheer entrepreneurial initiatives; or it may be explained as a “side-effect” that follows the adoption of the Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2006 by the United Nations which “facilitate[s] the equal participation of persons with disabilities in all modern society manifestations” (Seel 2020: 19).[2]

In any case, this bulk of recent or relatively recent publications leads us to two central thoughts that have to be seen as being intertwined with each other: (1) the research field of intralingual translation is nourished by a new fertile matrix of abundant empirical material; (2) this obviously quickens the interest to investigate the quality of these intralingual translations of the Bible and its potential implications for intralingual translation theory. We will reach out to this endeavour based on a German publication that was released in 2005 to trouble the windy waters of Bible translation: the Volxbibel.

First, a few introductory words on this synchronic intralingual translation of the Bible. The Volxbibel was initiated by the theologian Martin Dreyer, who had been working for several years with youngsters in a Cologne youth centre in Remscheid, Germany. There, he became aware of the necessity to make the Biblical texts comprehensible and, as such, mentally accessible to young Germans who are not used to reading and who do not have a Christian socialisation/education. Dreyer’s mission was to make them better understand the Biblical texts by relating them to their own lives more easily and to establish a relationship with God. To achieve this goal, Dreyer intralingually adapted already existing German translations of the New Testament by extensively using modern youth language.

Since 2006, the Volxbibel-project has been an online crowdsourcing project, the so-called “Volxbibel-Wiki,” where the Biblical texts have been publicly intralingually translated and are constantly updated.[3] Recently, the wiki moved to a Google Docs Site.[4] There is also a Volxbibel-Podcast as well as an Audio-CD of the Volxbibel.[5] Since 2019, the Volxbibel has offered free apps for iOS and Android smartphones. There is also an independent publishing company, the Volxbibel-Verlag. Until 2012, the Volxbibel had sold more than 250,000 copies.[6] In autumn 2014, a Volxbibel volume, including both the Old and the New Testaments, was published (Dreyer 2014).

Dreyer does not explicitly mention the source-text-version(s) he grounds his intralingual translation on. According to the German Bible Association, he probably relied on the Nestle-Aland and the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, as well as on the Textus receptus as source-texts.[7] However, at least with regard to the former and the letter, this is highly doubtful as Dreyer does not know Ancient Greek.[8] It is to be assumed that the author mainly used the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia and also relied on other German Bible translations. Thus, the Volxbibel has been initiated foremost as a second-hand intralingual translation. This is confirmed by the author himself. In one of his first announcements of the project in 2005, Dreyer explicitly refers to the Volxbibel as a modern “intralingual translation.”[9] Later on, probably due to protest and the uproar it generated in German Christian society, Dreyer spoke of it as a “Bearbeitung,” that is, “adaptation,” or as a “freie Übersetzung,” that is, a “free translation” which uses modern language.[10]

But how can the Volxbibel be defined in terms of Translation Studies? We would like to stress already at this point of the discussion that the main transfer characteristic of the Volxbibel is that it makes excessive use of local intralingual adaptive strategies only, but not global strategies (Bastin 2011; Bastin 2014), the latter being the strategy to follow when producing a target product of more “radical” changes, such as, for example, “adapting a novel for a play” (Volkova and Zubenina 2015: 91).[11] Here, however, in the Volxbibel, no part of the source-content is omitted, nor is the macro-structure altered or the medium as such changed. Any adaptive transfer actions are confined to semantic and/or pragmatic in-text-alterations on the level of the word or, in some cases, of the whole utterance/verse. The linguistic register, the cultural specificities, the religious terminology of the source-texts are substituted in the target-text by German youth language, including slang expressions and the latest culture-specific references of the targeted age and social group (see Section 2). Psalms are rendered intralingually as rap, poems and songs that rime. The religious parables and secular items of biblical times are adapted to equivalent schemes of our times, by abundantly using Anglicisms, slang and foul language. Thus, for example, the resurrection is briefly called “Jesus’ is celebrating his comeback.” (“Jesus feiert sein Comeback.” [Matt 28, 1; Dreyer 2014: 1710]) The angel who appeared to the two Marys at the open tomb and who told them about Jesus’ resurrection “shone almost like a lightning and his clothes were white as snow.” (“leuchtete fast so hell wie ein Blitz und seine Klamotten waren weiß wie Schnee.” [Matt 28, 3; Dreyer 2014: 1710]) The soldiers at the grave “wet their pants with fear” (“machten sich fast in die Hosen vor Angst.” [Matt 28, 4; Dreyer 2014: 1710]), while the women were “super happy.” (“superglücklich.”) [Matt 28, 8; Dreyer 2014: 1710] It is teeming with expressions such as “if God takes over completely the joystick of this world,” (“wenn Gott […] den Joystick der Welt komplett in die Hand [nimmt].” [Matt 22, 2; Dreyer 2014: 1691]), “Jesus’ McDonalds,” (“Jesus’MacDonald’s” [Matt 14, 15; Dreyer 2014: 1673]), “He probably didn’t give a damn about it,” (“aber es ging ihm wohl am Arsch vorbei.” [1. BüdK 11, 10; Dreyer 2014: 624]), “hit a really big win” (“ganz fett absahnen.” [Matt 5, 12; Dreyer 2014: 1646]), “be up for it” (“Bock drauf haben.” [Hes 45, 5; Dreyer 2014: 1504]), and many more.[12] Given the above, the Volxbibel has to be regarded as an intralingual adaptation. It could also be designated as being an “intralingual translation as popularisation” based on adaptive strategies on the micro-level only. The Translation Studies literature refers to this form of strategy on the micro-level as “local adaptation” (Bastin 2011: 5) and has to be regarded as one possible strategy among others in the context of translation.

It is obvious that any form of adaptation genuinely entails changes with regard to its source and these changes are mainly guided by its target audience and its overarching skopos. This is also the case in the Volxbibel (see Section 2). As previously mentioned, this intralingual adaptation as popularisation target group declared skopoi are (a) to make the messages of the Bible comprehensible and (b) to make a cultural product accessible and, through this, to foster social inclusion of German youngsters with no theological socialisation/education. Dreyer posits that the Volxbibel serves as a medium of cultural accessibility, that is, a medium that makes cultural products accessible and, hence, leads to better social inclusion.[13]

One should note that “accessibility” constitutes, according to the European Disability Forum (EDF) with reference to Article 9 of the CRPD, an essential human right (Greco 2016: 5; Greco 2018). This is also reassured by the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), which adopted in 2014 an Opinion (as a result of a public hearing in 2013) in which it acknowledges that “Article 9 of the CRPD constitutes a human right in itself, and as such it is pivotal for the full enjoyment of civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights of persons with disabilities.”[14]

However, what is all too problematic is that the Volxbibel’s in-text-alterations entail an extreme distancing of the semiotic gamut of the canonical original(s) (see Section 2). Hence, the question arises whether the Volxbibel as an intralingual adaptation as popularisation really makes the original messages of the Bible comprehensible, and if so, to what extent? And does it serve as a medium of cultural accessibility for its special target group and, through this, also as a medium of social inclusion? And if so, at what cost? And, moreover, what are the issues in terms of translation ethics (see Section 3.1) that the Volxbibel as a an intralingual translation based on local adaptive strategies touches upon? In view of the above, there are the following research questions that emerge from a semiotic and translational point of view, which are obviously interconnected:

-

As a new modern narrative of the biblical text, does the Volxbibel succeed in bridging cultural difference over time and in conveying the Scriptures to contemporary young Germans with no theological socialisation/education?

-

Does the Volxbibel really achieve cultural accessibility and, by this, social inclusion?

-

To what extent does the Volxbibel, as intralingual translation, conflict with translation ethics?

-

Where should the limits be set between adaptive intralingual transfer strategies and the achievement of accessibility/social inclusion through translation?

-

What are the implications of all of the above for (intralingual) translation theory?

I would like to attempt an answer to these questions with the help of some selected text examples from the Volxbibel, which were chosen based on the magnitude of their semiotic quality as local adaptations on the micro-level. These text excerpts will be shortly presented, analysed and contrasted with the according text segments of the Lutherbibel as an assumed source-text, which is a canonical version of the Bible.[15] Methodologically, the analysis has to be twofold: it will have to semiotically analyse the target-text segments of the Volxbibel, which will then be contrasted with the analysis of the same segments in the modern Lutherbibel, which is the classical and canonical German translation of the Scriptures and assumed source-text.[16] The analysis will take the whole semiotic gamut of the contrasted text segments into account. It is therefore helpful to make use of an approach in the analysis that, on the one hand, considers the various aspects of linguistic signs, but on the other hand also allows the investigation of extralingual, pragmatic and cultural dependencies as well as communicative intentions in comparison to both target-text segments and source-text segments. To this end, the analysis will be based on two main pillars: the first of the two pillars is a contrastive pragmatic approach as developed by Batsalia (1997), which itself is grounded on the speech act theory of Austin (1962), Searle (1969) and the well-known German linguists Maas and Wunderlich (1976), but also lends from structuralism (Saussure 1967). According to Batsalia (1997: 88), linguistic signs comprise a specific form and a specific content. The content has a cognitive side, which includes denotative and connotative elements as well as an associative and an emotive side. This will help analyse the semiotic gamut and the layers of meaning of both the target-text segments as well as the source-text segments. However, in cases where the text segment under discussion requires a more profound theological interpretation, the analysis will recur to canonical biblical criticism as a point of reference of established hermeneutical validity, which is the second pillar of analysis.[17]

The utmost aim of this article is, other than offering answers to the aforementioned five research questions, to nourish and foster the discussion on the intricate domain of synchronic intralingual translation(s) of the Scriptures which, ultimately, may deliver new insights in intralingual translation theory.

2. Contrastive pragmatic analysis of the Volxbibel[18] and the Lutherbibel: five examples

Based on the aforementioned approach, in the following section, selected target-text forms/segments/verses of the Volxbibel will be analysed and contrasted to the according text forms/segments/verses in one of the conventional, canonical German Bibles, probably the most well-known one, the Lutherbibel, as an assumed source-text. The aim of this contrastive analysis is to unveil the semiotic alterations in the intralingual rendering by the Volxbibel with regard to the canonical biblical text.[19] To this end, wherever necessary, the verses/segments/forms under discussion will be illuminated by contemporary canonical exegesis.

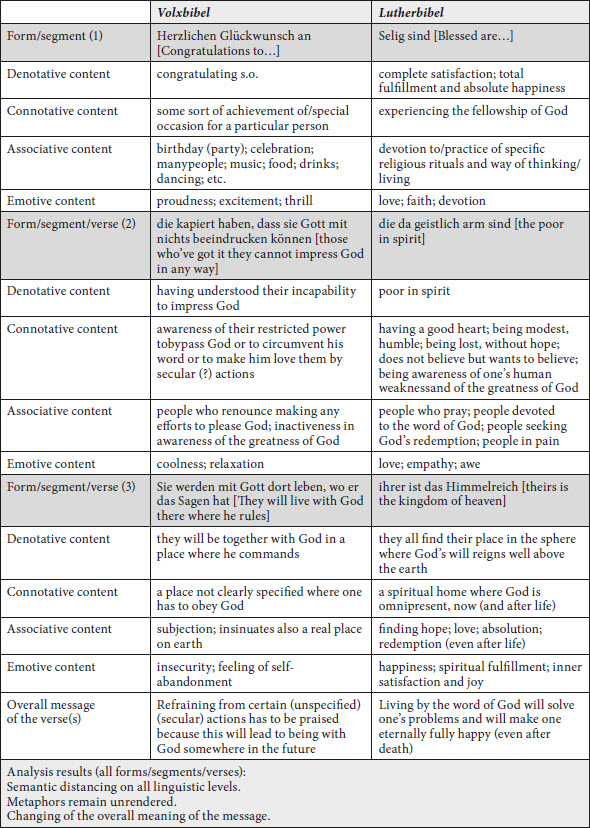

Table 1

Contrastive analysis 1

How can the results of this analysis be justified? As we can ascertain, there is no semiotic convergence of how the Beatitudes reads in the Volxbibel with the canonical text in any of its segments. As Table 1 shows in an elaborate manner, the semiotic distancing in every category of investigation between the Volxbibel and its canonical counterpart is numerous. For reasons of space and brevity, I will only mention the decisive differences hereafter.

We ascertain on all levels of analysis that the semiotic multiperspectivity of the canonical text and its metaphors remain unrendered. Hence, the overall meaning of the verse is changed. Thus, even if “selig” [blissful] is initially more difficult to understand for some young people than the everyday expression “to get into a good mood,” this biblical technical term means much more than a momentarily elevated mood. This particular term reads in the Greek original as μακάριος [makarios], a word that describes the state of complete satisfaction, total fulfillment and absolute happiness that is experienced in fellowship with God. Thus, blessed is one who is completely filled with God, regardless of earthly circumstances. This is definitely more than just to be “congratulated.” Also in segment/verse (2), the semiotic deviance is amazing, as the polyvalent nature of the adjectives “geistlich arm” [poor in spirit] with its religious underpinnings (love, empathy, awe) is monovalently rendered by “mit nichts beeindrucken können” [they cannot impress God in any way]. This goes also for the rendering of the segment “ihrer ist das Himmelreich” [theirs is the kingdom of heaven] with the verse “Sie werden mit Gott dort leben, wo er das Sagen hat” [They will live with God where he rules]. Not to speak of the overall message of this important verse of the Bible (see Table1), which is in the Volxbibel completely altered in contrast to its canonical counterpart, as it leaves the reader with a flattened and unspecified attitude towards God and his word, insinuating at the same time a certain kind of passive subjection to him.[21]

Let us now proceed to a second example that will illuminate more the semiotic particularities of the Volxbibel.

2)

Volxbibel: “Universal-PIN-Code von Gott”

Offb 7.2.; 9.4; Dreyer 2014: 2164, 2167

[“universal PIN code of God”; my translation]

a)

Lutherbibel: “Siegel des lebendigen Gottes”

Offb 7.2.; 9.4

[“Then I saw another angel coming up from the east, having the seal of the living God”]

NIV, Rev 7.2., 9.4

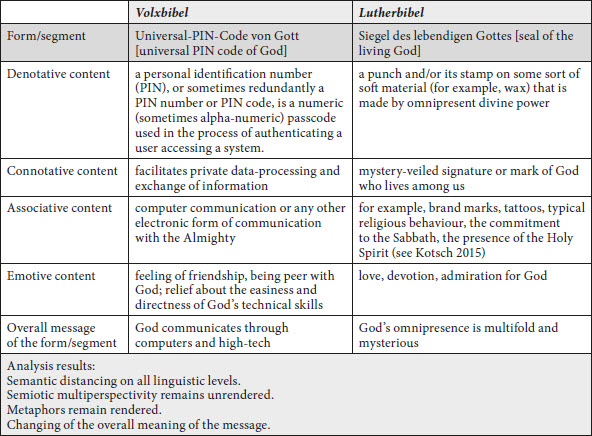

Table 2

Contrastive analysis 2

Here, once again, we can ascertain on all levels of analysis that the semiotic multiperspectivity and the metaphors of the canonical text remain unrendered, which leads to a changing of the overall message of the verse. The justification of the results of this analysis is obvious. The exegetical tradition has given many different interpretations of the “seal of God.” According to canonical exegesis it may represent, among others, brand marks, tattoos, typical Christian forms of behaviour, the commitment to the Sabbath, the presence of the Holy Spirit (Kotsch 2015). In the Volxbibel, this quickly becomes the “universal PIN code of God.” In view of current technical possibilities, a divine PIN code makes perfect sense. At the same time, however, in order to attain its skopos of a popularising intralingual translation, this definition restricts the range of possible meaning variants without reason and also reduces the emotive content which the Scripture conveys according to canonical exegesis (Paulien 1992: 61-63).

Now, let us look at a third example.

3)

Volxbibel: “Was denkt denn ihr: Wenn jemand hundert Meerschweinchen (form/segment 1) hat und eines büchst plötzlich aus dem Stall aus (form/segment 1) und ist verschwunden, was macht der dann? Er wird sich doch sofort aufmachen und seinen ganzen Garten durchsuchen, bis er das eine Meerschweinchen gefunden hat”

Mt 18,11-14; Dreyer 2014: 1682

[“What do you think: If someone has a hundred guinea pigs and one suddenly escapes from the stable and disappears, what does he do then? He’ll set out right away and search his whole garden until he finds this guinea pig”; my translation].

a)

Lutherbibel: “Was meint ihr? Wenn ein Mensch hundert Schafe hätte und eins unter ihnen sich verirrte: lässt er nicht die neunundneunzig auf den Bergen, geht hin und sucht das verirrte?”

Mt 18, 11-14

[“What do you think? If a man owns a hundred sheep, and one of them goes astray, will he not leave the ninety-nine on the hills and go to look for the one that wandered off?”]

NIV, Mt 18, 11-18

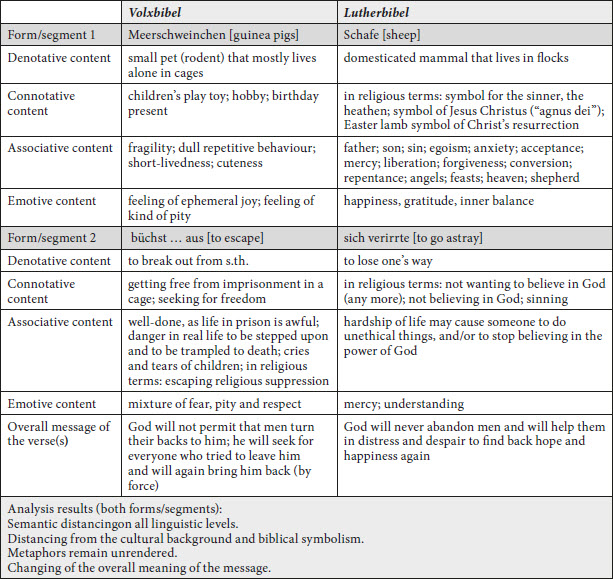

Table 3

Contrastive analysis 3

As in the other two text examples of the Volxbibel before, we here also notice on all levels of analysis a semantic distancing as well as a distancing from the cultural background and its biblical symbolism, a non-rendering of metaphors, all which, again, leads to a changing of the overall message of the verses as conveyed by the parable that represents a vision of a better world. Concretely, these results can be justified as follows: the cultural background to which Jesus refers with his parable of the lost sheep is completely neglected in the translation of the Volxbibel. The hundred sheep become one hundred guinea pigs (Mt 18, 11-14) and in the parallel passage twenty cats (Lk 15: 1-7). The Volxbibel does not take into account canonical biblical symbolism, nor does it awaken the inner-biblical associations of Christians as “sheep” (Mt 10: 16) and the one of Jesus Christ as “Lamb of God” (Acts 8: 32). Not to speak of the unrendered metaphor through the translation of “sich verirren” [to go astray] by “ausbüchsen” [to escape], the former being a metaphor for “losing oneself (unwillingly) in the tribulations of life or/and losing faith,” and, by that, becoming a sinner, whom God, disguised as a good shepherd, does not forsake and helps find again the right way, as long as the “gone-astray” is willing to follow His will. The latter choice, that is, “ausbüchsen” [to escape], evidently does not convey this metaphorical meaning.[22]

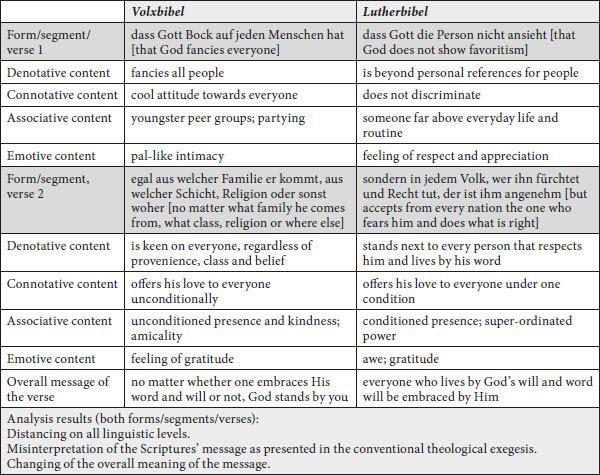

4)

Volxbibel: Petrus legte los: “Ich hab jetzt erst richtig begriffen, dass Gott Bock auf jeden Menschen hat (form/segment 1), egal aus welcher Familie er kommt, aus welcher Schicht, Religion oder sonst woher (form/segment 1)”

ApG 10, 34; Dreyer 2014: 1903

[Then Peter opened his mouth and spoke: “I’ve only now really understood that God fancies everyone, no matter what family he comes from, what class, religion or where else.”; my translation]

a)

Lutherbibel: Petrus aber tat seinen Mund auf und sprach: “Nun erfahre ich in Wahrheit, dass Gott die Person nicht ansieht; sondern in jedem Volk, wer ihn fürchtet und Recht tut, der ist ihm angenehm”

ApG 10, 34-35

[Then Peter began to speak: “I now realize how true it is that God does not show favouritism but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right”]

NIV, Acts 10, 34-35

Table 4

Contrastive analysis 4

How can these results be justified? Besides the colloquial style used (which, of course, is justified by the utmost aim to better reach the addressed target group), we ascertain again a distancing on all levels of analysis that leads to a misinterpretation of the Scriptures’ message and, therefore, to a changing of the overall message of the verse. God’s love for the representatives of other religions is conveyed as to correspond to a pluralistic zeitgeist, but not to the biblical original. Of course, God does love everyone. The wording chosen here could easily give the reader of the Volxbibel the impression that the followers of a non-Christian religion would also spend eternity with God if they only tried to live decently. However, according to canonical exegesis, this would not suffice, if they did not live by Gods will and word (Kotsch 2015).

We move now over to our last example.

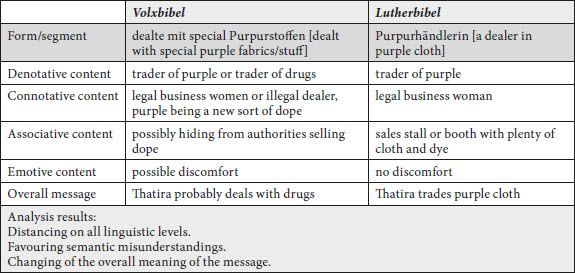

5)

Volxbibel: “Wir pflanzten uns zu ihnen und quatschten ‘ne Runde mit den Frauen, die gerade da waren. Eine von denen hieß Lydia […]. Sie kam ursprünglich aus Thatira und dealte mit special Purpurstoffen”

ApG 16, 13-14; Dreyer (2014: 1916-1917)

[We plonked ourselves to them and chatted with the women who were there. One of them was called Lydia […]. She was originally from Thatira and dealt with special purple fabrics/stuff”; my translation]

a)

Lutherbibel: “[…] und wir setzten uns und redeten mit den Frauen, die dort zusammenkamen. […] Und eine Frau mit Namen Lydia, eine Purpurhändlerin aus der Stadt Thatira, eine Gottesfürchtige, hörte zu”

ApG 16, 13-14

[“We sat down and began to speak to the women who had gathered there. One of those listening was a woman from the city of Thyatira named Lydia, a dealer in purple cloth”]

NIV, Acts 16, 13-14

Table 5

Contrastive analysis 5

These results can be justified as follows: as we can infer from the distancing on all levels of analysis, the Volxbibel favours misunderstandings, which lead to a changing of the overall message of the verse. Whoever reads in it that Lydia “deals with special purple fabrics/stuffs” might get the obvious misunderstanding in German that she deals with drugs because the meaning of the German word “Stoff” is ambivalent, as it may mean “fabrics,” but it can also mean “drugs”/“dope.” However, what is meant in the canonical counterpart is that Lydia sold purple as a valuable cloth or rare dye.

In view of the above, we can conclude that in all five examples of the Volxbibel, the semiotic distancing on all four levels of linguistic analysis have to be regarded as decisive, affecting the level of culture too. In this context, we ascertained that the semiotic multiperspectivity of the canonical text remains unrendered as well as a distancing from the cultural background and biblical symbolism, the non-rendering of metaphors, which obviously leads to a changing of the Scriptures’ message and to the favouring of misunderstandings. Hence, in all five analysed examples, the overall message of the canonical text’s verse(s) was altered. This obviously also leads to the conclusion that the analysed verses of the Volxbibel lack in every one of the five cases semiotic affinity to the canonical exegesis of the Bible.

On these grounds, we will now attempt to give answers to the five research questions, focusing thereby on the ethical dimension of translation and applying it to the Volxbibel as a declared means of cultural accessibility and social inclusion.

3. Answers to the research questions

3.1 Is the Volxbibel a means of cultural accessibility and social inclusion?

Though, at first glance, the local adaptive translation strategy seems to bridge cultural differences over time, this is in reality not the case when taking into account the peculiarity of the biblical texts, which is due to its religious messages encoded in single words, verses, parables with multiple layers of polysemy. However, as we have shown in Section 2, in the Volxbibel, the canonical exegesis of the Bible texts is extensively and semiotically altered with their overall message changed. It is thereby evident that, in its attempt to reach its target group, the Volxbibel puts man into the centre of interest and not God himself. One can assume that this is to be seen as an integral part of the intralingual popularisation’s overall skopos and, as such, a correct approach. However, with regard to the claim that the Volxbibel serves as a medium of cultural accessibility (see Section 1), it has been shown that the bridging of cultural differences over time can be regarded as superficial and semiotically misleading. However, sufficient cultural accessibility can only be granted if the intralingual translation does not alter semiotically the original messages to be transferred into the target-culture. With this in mind, the Volxbibel’s intralingual transfer of the Scriptures to young Germans with no theological socialisation/education has to be regarded as deficient and, therefore, unsatisfactory. If accessibility to cultural assets and heritage has to be granted through intralingual translation, and if this is to be determined as one important translational skopos, this can only be substantially achieved if intralingual translation is a vessel of transfer of the (assumed) source-text’s content and its author’s intentions, that is, if the semiotic dimensions and the overall messages of the canonical text’s verses are rendered according to the meaning and messages of the scriptures. However, in favour of reaching the skopos of popularising the Bible, the intralingual renderings of the Volxbibel lead to decisive semiotic changes with regard to the biblical messages and sense and to an imprecise rendering of God’s word in the sense of its generally accepted canonical exegesis.

In view of the above, and also in view of the abundance of such semiotic alterations throughout the whole target-text, my first and second research question (see Section 1) can be answered as follows: one can posit that the Volxbibel as a new modern narrative of the biblical text does not succeed in bridging cultural difference over time by, at the same time, truly transferring the Biblical text to contemporary young Germans with do not have a theological socialisation/education as its target group. It goes without saying that this only very insufficiently grants cultural accessibility and, by means of this, in-depth social inclusion to German youngsters with the aforementioned characteristic; one can also posit that the Volxbibel merely achieves an outward accessibility and social inclusion of the targeted group. Furthermore, the great distance of the Volxbibel from the receptive canon of Bible translation in German culture may also lead to a certain kind of self-imposed isolation of German youth readers of the Scriptures, thus fostering the growth of the generation gap.

3.2 The Volxbibel and translation ethics

In this section, I would like to give answers to the third and fourth research questions, that is, to what extent the Volxbibel, as an intralingual translation, conflicts with translation ethics and where the limits should be set between radical intralingual transfer strategies and the achievement of cultural accessibility/social inclusion through translation? In order to do so, it is necessary to firstly define “ethics” in order to have a standard point of reference of this particular notion. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, “ethic(s)” can be defined as 1. “a set of moral issues or aspects” and 2. “[…] dealing with what is good and bad and with moral duty and obligation […].”[23] Both of these definitions insinuate two central issues that are interrelated: ethics is directly dependent on the “Other.” It is specified by this and ethics also presumes that the encounter with the Other is guided by specific sets of behaviour and values that are commonly acknowledged; and, in the case that both these issues are not respected, any such case will conflict with ethics. The problem that arises, however, is how these specific sets of behaviour and values are defined. As such, they are subjected to relativity, as they may differ from culture to culture, from historical period to historical period and, of course, from one domain of application to another.

In these terms, it can be posited that the ethical dimension in translational action essentially refers to the relation between the source-text and the target-text as well as to the criteria of translational transfer, which take duly into account the specificities of both sides without inflicting conflict.

However, being a notion subjected to relativity, “translation ethics” reaches a wide span of definitions, depending on the theoretical approach that guides translation action. But, regardless, whether it is more narrowly or more widely defined, there is always a common denominator in all approaches, which is always the aforementioned relation between the source-text and the target-text.

In Translation Studies, there are several approaches that deal with translation ethics differently, which is due to a different way of how translation is perceived and, as such, theoretically grounded. As it would exceed the limits and the scope of this article, a selection of only four central, but more or less diverging, approaches will be mentioned to illustrate their wide gamut.[24]

The first two do not refer to the ethical dimension of translation explicitly, only implicitly. A first and more narrow approach to translation ethics concentrates on the term “fidelity” (Henry 1995) and is associated with the concept of “equivalence” (Halverson 1997; see also Prunč 2005: 175). However, this is not the sole standard of ethical assessment of translational action. The extreme opposite and wider approach is represented by Skopos theory (Reiss and Vermeer 1984/1991) which replaces the demand for equivalence through the demand for adequacy, which is reached when the purpose (skopos) of the translation is achieved.[25]

Between these two ends, there are two other approaches that seem to reconcile both extremes and explicitly refer to the ethical dimension of translation. One of these approaches is Nord’s (1989) functionally oriented dynamic concept of “loyalty,” according to which a functionally correct translation has to respect all the determinants involved in translational action, that is, the client’s commission and the recipients of the target-text, but, at the same time, also the author of the source-text and his intention(s) which are embedded in the source-text. This compatibility of the translation skopos with the source-text is a culture-bound desideratum and altering the intention of the source-text author would result in an “unethical” translational transfer (Nord 2011: 27).

In quite a similar sense, but from a different angle, from the one of “Translationskultur” [translation culture], Prunč (2005) demarcates the boundaries in which a translation is still to be regarded as ethical. His seminal term “translation culture” is defined as follows:

The social framework within which the ethical actions of translators are to be judged is […] called “translation culture.” Translation culture is a historically grown, self-referential and self-regulating subsystem of a culture that has evolved from developing a dialectical relationship to translation practice; this subsystem of culture focuses on the field of translation which is made up by a set of socially established, controlled and controllable norms, conventions, expectations attitudes and values as well as habitualised behaviour patterns that regard all those who are currently or will be potentially involved in translation processes in this culture.

Prunč 2005: 176; my translation

According to Prunč (2005: 175), translation ethics must go beyond textuality and take into account the entire socio-political and ideological context as well as hierarchies of both the source and the target-text. Within this framework, translators have to make decisions which account to it. Only then would an ethically adequate translation would be completed.

In my opinion, the first two approaches, the two opposite ends, impose limitations on the correlation between the intralingual translation under discussion and the ethical issue of translation. The first is too restrictive as it delineates ethical translation on the grounds of equivalence, which has been proven by Translation Studies research to be unfruitful in terms of cultural and textual transfer (see, for example, Reiss and Vermeer 1984/1991: 30; Snell-Hornby 1988: 17, 18; Stolze 1992: 62-64). Here, the focus is too much on the source-text, thus neglecting any cultural or textual issues of the target-text, as well as the scope of translational action. The second one, though absolutely “functional” (also in the wider sense) and, undoubtedly, a helpful instrument in the hands of translators for targeted translational action, is, however, not specific enough when it comes to determining the ethical parameters in the relationship between source-text and target-text. Does a functionally equivalent translation (Reiss and Vermeer 1984/1991) explicitly respect the source-text author’s intention? What if the text author’s intention is changed despite the congruence of the functions of the source-text and the target-text? We can assume that this is potentially even more aggravated when a source-text is translated on the grounds of adequacy where the function of the source-text and that of the target-text differ. In this approach, the focus lies on the target-text and its scope as the utmost translational axiom. This becomes evident in their hierarchically linked “General rules for translational action” where for Reiss and Vermeer (1984/1991: 119) the “coherence” of the translatum with the source-text is only the fifth of, in total, six rules (the last one being the one of their hierarchical linking). Thus, this approach faces two obstacles with regard to translation ethics: 1. Functional Skopos theory does not attach due importance to the compatibility of the Sskopos with the source-text, and 2. although the congruity of the source-text author’s intention and that of the target-text may be given, it is also not explicitly presupposed as such by the theoretical grounding of this particular approach. This makes possible a wide gamut of translational actions among which target-texts can also be generated that are not at all or only loosely source-text-bound. It is evident that such target-text conflict with translation ethics as defined in the beginning of this section.

Given the above, translation ethics are, in my opinion, more precisely demarcated by Nord’s concept of “loyalty” as well as by Prunč’s concept of “translation culture,” especially when combined in a complementary approach. In such a complementary approach, the source-text author’s intention is explicitly set as a main parameter of translational action and, at the same time, the entire socio-political and ideological context of both the source and the target-text are explicitly accounted for.

On the grounds of the aforementioned two latter concept/approaches to the ethical parameters of translation, we can contend that the Volxbibel conflicts with translation ethics, at least as shown above based on a characteristic selection of Translation Studies approaches. As shown by the analysis (see Section 2), we ascertained an intense submission of the source-culture and its ideological aspects as well as an altering of the intentions of the canonical text (as assumed source-text) through extensive and extreme local adaptive mechanisms that disregard the importance of the aforementioned concepts. In a sense, one can posit that the intralingual translation of the Volxbibel imposes a cultural hegemony of the target-culture on the biblical source-text. As a result, not only is a semiotically deviant intralingual translation produced, one which challenges the ethical dimension of translational action as determined above, but, in addition, a weird “third space”-target-text is made, which is dissociated from the vast majority of society and of the literary canon of Bible translation, while transposing the Holy Word in a monodimensional manner.

Hence, we can conclude that adaptive intralingual transfer strategies can only achieve cultural accessibility and, by that, social inclusion, when they are limited by a well-tempered equilibrium between the semiotic diversifications with regard to the source-text, implemented by the intralingual translation transfer actions that aim at reaching the target group, and, at the same time, the respect of the source-text author’s intention and its socio-political and ideological context. This is all the more important when it comes to the intralingual transfer of the Scriptures, whose polysemiotic nature is, to a great extent, hermeneutically predetermined by diachronic canonical exegesis of the past several centuries.

3.3 Some thoughts on the Volxbibel’s impact on (intralingual) translation theory

What are the implications of all the above for (intralingual) translation theory? Based on what was previous stated (see Sections 3.1 and 3.2), if intralingual translation is to go along with the ethical parameter of translation, it has to clearly adopt transfer strategies that harmonise with Nord’s (1989; 2011) concept of “loyalty” and with Prunč’s (2005) complementary, more holistic concept of “translation culture.” While both authors conceive their concepts with regard to interlingual translation, we can ascertain, from the above analysis, that the ethical aspect, as one distinctive feature of the nature of interlingual translation, can also be applied in an unaltered manner to intralingual translation as intrasemiotic transfer by using the same theoretical concepts. In view of this, we can ascertain a common ground for both interlingual and intralingual translation, thus affirming their conceptual proximity. This is all the more important as research in intralingual translation strives for the conceptual integration of intralingual translation in the field of Translation Studies as equal to interlingual translation (see, for example, Zethsen 2007; Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen 2016; Korning Zethsen 2018).

In view of the above, and also answering my fifth research question (see Section 1), I believe that there is at least one more implication for Translation Studies and intralingual translation. In order to conceptually integrate intralingual translation in the realms of Translation Studies, a broad definition of “translational transfer,” which could bear in it both central transfer modes, was conceived. This was, in short, successfully achieved by merging Toury’s (1995: 33) postulates (1. the Source-text Postulate, 2. the Transfer Postulate and 3. the Relationship Postulate) with the theoretical axioms of functional Skopos theory (Reiss and Vermeer 1984/1991). This criterial definition, first presented in Zethsen (2007) and, later, slightly modified, again presented in Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016), delineates the field of Translation Studies and succeeds in conceptually encompassing therein also intralingual and intersemiotic transfer action (in Jakobson’s 1959 sense). The definition reads as follows:

-

A source-text (verbal or non-verbal) exists or has existed at some point in time.

-

The target-text has been derived from the source-text (resulting in a new product in another language, genre, medium or semiotic system).

-

The resulting relationship is one of relevant similarity, which may take many forms depending on the skopos. (Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen 2016: 705)

In view of the results and conclusions with regard to the ethical aspect of translation, this criterial definition does, in my opinion, not take any specific stance on the ethical dimension of translational transfer. On the contrary, it leaves open a space for transfer products of either interlingual or intralingual nature that also may deviate from the ethical dimension of translation as defined above. Such transfer products may be, for example, global adaptations, travesties or “versions” (Nord 2011: 25) or any kind of “assumed translations” (Toury 1980) which trespass the border of ethically grounded translational transfer strategies. This is exactly the case with the Volxbibel which, in these terms, could be also characterised as an “intralingual version” in Nord’s sense.

Hence, if we accept that this definition is open to any kind of transfer, even ones that are not guided by ethical criteria as shown above (see Sections 3.1 and 3.2), it theoretically can bear in itself any kind of transfer whatsoever (for example, the Volxbibel as an intralingual version of the Bible). However, if we want to limit its applicability to translational action with a concern of ethically grounded transfer, Nord’s concept of “loyalty” and Prunč’s main parameters of his “translation culture” concept, should be, in my opinion, included in this definition because, as has been explained in Section 3, the skopos itself does not necessarily presuppose the target-text’s compatibility with the source-text author’s intention and its socio-political and ideological context. Therefore, with regard to the dimension of the ethics of translation, I propose slightly adjusting this definition with the following addition (in italics):

-

A source-text (verbal or non-verbal) exists or has existed at some point in time.

-

The target-text has been derived from the source-text (resulting in a new product in another language, genre, medium or semiotic system).

-

The resulting relationship is one of relevant similarity, which may take many forms depending on the skopos.

-

This relationship is compatible with the source-text author’s intention and with the source-text’s socio-political and ideological context.

There is no doubt that this addition, based on the grounds of the ethical parameter, admittedly restricts the wide gamut of the definition’s applicability (besides making the definition also a bit longer). However, I believe that it may prove to be helpful with regard to its primary aim, that is, the delineation of the boundaries for translational transfer as such, both as interlingual and intralingual transfer, leaving out of these boundaries—in an explicit manner—phenomena of semiotic transfer that are characterised by extreme distancing of the source, regardless of their declared skopos (for example, as mentioned above, global adaptations, travesties, “versions” in Nord’s sense, such as the Volxbibel) where the ethical component is neglected (and probably, have their conceptual belonging in another discipline, for example, adaptation studies). Moreover, this added limitation, with which, as the analysis of the Volxbibel has shown, intralingual translation also totally complies, clearly points to the common grounds between intralingual and interlingual translation. This may contribute to viewing even better the proximity of these two transfer modes and to fending off any critical voices that posit that intralingual translation does not count as “translation” and therefore argue that it conceptually has no place in the field of translation studies (see, for example, Hermans 1995; Koller 1995; Mossop 2016).

4. Conclusion

It has been demonstrated, on the grounds of the analysis of the Volxbibel, that the goal of achieving cultural accessibility through intralingual translation and, through this, of also achieving the social inclusion of the target group can only be accomplished if intralingual translation and the transfer strategies implemented take thoroughly into account the ethical dimension of translation, at least as shown above (see Sections 3.1 and 3.2). In the Volxbibel, it has been found that this is not the case. Therein, the implemented local adaptions to modern German culture and language used as a central intralingual translation strategy compromise the overarching religious semiotics of the Scriptures as presented by the canonical exegeses for the sake of every-day communicability, thus altering to a great extent the canonical meaning of the biblical text. This has led us to the conclusion that, if such semiotic alterations and ethical distancing of the source-text are to be avoided, intralingual text transfer can help itself by orienting its approach on the grounds of Nord’s concept of “loyalty,” while also taking into account Prunč’s concept of “translation cultures” in a complementary manner to the former. This will assure that both the target-text’s function, the target group and the source-text author’s intentions as well as the socio-political and ideological context of the source-text are duly interconnected semiotically in an ethically grounded osmosis of intralingual text transfer.

Finally, given the above, we drew conclusions on (intralingual) translation theory. With regard to the signification of the ethical dimension of translation, it was concluded that Zethsen’s and Hill-Madsen’s wide criterial definition of “translation” does not explicitly take into account the ethical dimension, leaving open a space for intralingual and interlingual transfer which may tend to be criticised as being out of the realms of translation and Translation Studies. Therefore, I have proposed a slight adjustment to the existing definition by including an ethical dimension in it. I hope that this will assist in more precisely delineating the boundaries of what a translation is and, at the same time, to more easily integrating intralingual translation in these boundaries, by illuminating one aspect of the common grounds both interlingual and intralingual translation reside on.

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix 1. Bible texts

Anon. (2008): Catholic Youth Bibles, NRSV. Winona, MS: Saint Mary’s Press.

Anon. (2011): New International Version (NIV) 2011. BibleGateway. Consulted on 15 August 2022, <https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-International-Version-NIV-Bible/>.

Anon. (2015): NIV Bible for teen girls: Growing in faith, hope and love. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Anon. (2017): Lutherbibel 2017. Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. Consulted on 30 July 2022, <https://www.die-bibel.de/bibeln/online-bibeln/lesen/LU17>.

Anon. (2020-): The Kingstone Bible. Leesburg, FL: Kingstone.

Cook, David C. and Cariello, Sergio (2010): The Action Bible: God’s redemptive story. Colorado Springs, David Cook.

Dreyer, Martin, ed. (2014): Volxbibel. Das alte und neue Testament, Stuttgart: Pattloch Verlag.

Dreyer, Martin, ed. (2022): Die Volxbibel 20.X. Volxbibel-online. Consulted on 15 July 2022, <https://lesen.volxbibel.de/>.

Notes

-

[1]

The biblical texts for children, for example, have been translated by the Organisation “Bible for Children” into 452 different languages since 2006 (Consulted 1. July, 2022, https://bibleforchildren.org/). For the smaller bulk of the main dominant languages, it can be assumed that intralingual translations were used, while for the numerous minoritized languages included in this project (for example, Afaan Oromoo, Susu, Sukuma and Zulu), interlingual translations must have been implemented; however, no clear specification is given). Moreover, intralingual English translations for teens were published from 2008 onwards, for example, the Catholic Youth Bibles (see reference for this and all Bibles in Appendix). English Bible translations for teen girls have also found their way to the shelves of the bookstores (e.g. Bible for teen girls: Growing in faith, hope and love). Finally, also comic book adaptations of the Bible, again in English, are available, for example, The Action Bible: God’s redemptive story; see also the Kingtsone Bible with 2000 pages in 1. volumes; most of them were (re-)published in the recent years 2020-2022. These are only a few of several other similar publications. Also very interesting in this context is the initiative of the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft [German Bible Society] to circulate the Bible in a multitude of ways among children (Kinder und Bibel. Consulted on 1. July, 2022. <https://www.die-bibel.de/bibeln/bibel-in-der-praxis/bibel-fuer-kinder/>).

-

[2]

See Seel (2020) for more information on the CRPD and its ramifications for the development of easy-to-read language, with focus on its implementation in Greek oral history testimonies for museum exhibitions.

-

[3]

See Volxbibel website, consulted on 15 July 2022, <https://wiki.volxbibel.com/Hauptseite>.

-

[4]

Consulted on 15 July 2022, <https://lesen.volxbibel.de>.

-

[5]

Consulted on 15 July 2022, <https://www.podcast.de/podcast/2361161/der-volxcast>.

-

[6]

At least according to Wikipedia. Consulted on 18 July, 2022, <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volxbibel>.

-

[7]

See the site of the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft [German Bible Society], consulted on 30 July, 2022, <https://www.die-bibel.de/bibeln/wissen-zur-bibel/wissen-bibeluebersetzung/deutsche-bibeluebersetzungen-im-vergleich/>.

-

[8]

See Hetmank, Maya (2008): Die Volxbibel–das Buch der Bücher als Sprachexperiment [The Volxbibel. The Book of Books as a Language Experiment]. Grin. Consulted on 22 July, 2022, <https://www.grin.com/document/123046>, with reference to Dreyer’s website in 2008.

-

[9]

See the editor’s website, Die Volxbibel. Das alte und neue Testament [The Volxbibel. The Old and the New Testaments], Droemer Knaur. Consulted on 12 July, 2022. <https://www.droemer-knaur.de/buch/martin-dreyer-die-volxbibel-9783629320513>.

-

[10]

See the descriptions on the popular sites, Wikipedia (consulted on 18 July 2022, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volxbibel); and Bibelberater[Bible Counselor] (consulted on 19 July, 2022, https://bibelberater.de/bibeluebersetzung/volxbibel/#%C3%9Cbersetzungstyp)

-

[11]

See Seel (2021: 7) for the differences between “local” and “global” adaptation.

-

[12]

See the review by Gessler, Philipp (2006). Jesus’ fettes Comeback [Jesus’ Awesome Comeback], Taz. Consulted on 21 July, 2022, <https://taz.de/Jesus-fettes-Comeback/!487452/>. The examples used have been translated by the author from German into English.

-

[13]

See again the information on Wikipedia and the review by Storch, Carston (2015). Stellungnahme Volxbibel, consulted on 23 July, 2022. <http://pastor-storch.de/2005/06/23/stellungnahme-volxbibel/>.

-

[14]

EESC (2014): Opinion on accessibility as a human right for persons with disabilities, European Economic and Social Committee, consulted on 12 July, 2022, <http://toad.eesc.europa.eu/viewdoc.aspx?doc=ces/ten/ten515/en/CES3000-2013_00_00_TRA_AC_en.doc>.

-

[15]

For reasons of brevity, the target-text segments will only be compared with the corresponding segments of the Lutherbibel as a main point of reference of a conventional, widely accepted German Bible text.

-

[16]

Luther translated both the Old and the New Testaments from Ancient Hebrew and Greek into the every-day German language of his time. As the Lutherbibel has been constantly intralingually revised since its first publication in 1534 (almost 500 years have passed since then), the recent 2017 version, which we use for our contrastive analysis, has to be regarded, in the wider sense, as an intralingual translation of Luther’s original translation. See Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (2022). Die Geschichte der Lutherbibel [The History of the Luther Bible, Luther Bible]. Lutherbibel. Consulted on 30 July, 2022, https://www.die-bibel.de/bibeln/unsere-uebersetzungen/lutherbibel/die-geschichte-der-lutherbibel/.

-

[17]

See Hayes and Holladay (2007: 154-156) with regard to the five distinctive features of canonical biblical exegesis/criticism. This article adopts the main axes of theological approach of canonical biblical exegesis/criticism which is that canonical exegesis/criticism is “interested in what the text means for the community.”

-

[18]

The edition which will be mainly used is the Volxbibel (2014), abbreviated as (VB). However, wherever regarded as necessary, the recent online-version 2022 (https://lesen.volxbibel.de/) will be consulted.

-

[19]

In order to make the analysis accessible to readers who are not fluent in the German language, the Volxbibel utterances under analysis will be translated by the author of this chapter into English and put in square brackets. In addition to the verses of the Lutherbibel, the equivalent verses of the English Bible, as found in the New International Version (NIV) of 2011, will always be given in square brackets too, for the same reason of maximum intelligibility for non-German speaking readers.

-

[20]

Volxbibel Online, consulted on 23 July, 2022, <https://lesen.volxbibel.de/book/Matth%c3%a4us/chapter/5>.

-

[21]

Kotsch, Michael (2015). Volxbibel – oder Jesus bei McDonald, Bibelbund [Volxbibel – or Jesus at McDonald’s, Bible Society], consulted on 14 July, 2022, <https://bibelbund.de/2015/05/volxbibel-oder-jesus-bei-mcdonalds/>; MEI, Juan (2022). Was für Menschen sind da geistlich arm? Die Bibel Studieren [Who are the spiritually poor? Studying the Bible]. Consulted on 16 July, 2022, https://www.bibel-de.org/die-geistlich-armen.html.

-

[22]

Jesus’ Gleichnis vom verlorenen Schaf. Wo ist Gott? [Jesus’ Parable of the Lost Sheep. Where is God?] Consulted on 29 July 2022. https://www.wo-ist-gott.info/wer-oder-was-ist-gott/jesus/gleichnisse/gleichnis-verlorenes-schaf.php; Gleichnis vom verlorenen Schaf, eine Liebesgeschichte. Postposmo [Parable of the Lost Sheep: a Love Story. Postposmo]. Consulted on 29 July, 2022. <https://www.postposmo.com/de/Gleichnis-vom-verlorenen-Schaf/>.

-

[23]

Ethic. Consulted on 30 July, 2022, <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ethic>.

-

[24]

See Prunč (2005) for a historical overview of ethics in translation theory. See also in this context also Robinson (2003).

-

[25]

The authors determine “equivalence” (Äquivalenz) as a product-oriented concept that refers to the relation of a source-text and a target-text when each of them fulfill the same function in their respective culture. “Adequacy” (Adäquatheit) is defined as a process-oriented concept that refers to the skopos the translator consistently respects when producing the target-text. See Reiss and Vermeer (1984/1991: 139).

Bibliography

- Austin, John L. (1962): How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bastin, Georges L. (2011): Adaptation. In: Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha, eds. Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London/New York: Routledge, 3-6.

- Bastin, Georges L. (2014): Adaptation, the Paramount Communication Strategy. Linguaculture. 1(1):73-87.

- Batsalia, Friederike (1997): Der semiotische Rhombus. Ein handlungstheoretisches Konzept zu einer konfrontativen Pragmatik [The Semiotic Rhombus. An Action-Theoretical Concept for a Confrontational Pragmatics]. Athens: Praxis.

- Greco, Gian M. (2016): On Accessibility as a Human Right, with an Application to Media Accessibility. In: Anna Matamala and Pilar Orero, eds. Researching Audio Description. New Approaches. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 11-33.

- Greco, Gian M. (2018): The nature of accessibility studies. Journal of Audiovisual Translation. 1(1):205-232.

- Halverson, Sandra (1997): The Concept of Equivalence in Translation Studies: Much Ado About Something. Target. 9(2):297-233.

- Hayes, John H. and Holladay, Carl R. (2007): Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner’s Handbook. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- Henry, Jacqueline (1995): La fidélité, cet éternel questionnement. Critique de la morale de la traduction. Meta. 40(3):367-371.

- Hermans, Theo (1995): Translation as institution. In: Mary Snell-Hornby, Zuzana Jettmarova and Klaus Kaindl, eds. Translation as Intercultural Communication: Selected Papers from the EST Congress, Prague 1995. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 3-20.

- Jakobson, Roman (1959): On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In: Reuben E. Brower, ed. On Translation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 231-239.

- Koller, Werner (1995): The Concept of Equivalence and the Object of Translation Studies. Target. 7(1):191-222.

- Korning Zethsen, Karen (2018): Access is not the same as understanding. Why intralingual translation is crucial in a world of information overload. Across Languages and Cultures. 19(1):79-98.

- Korning Zethsen, Karen and Hill-Madsen, Aage (2016): Intralingual Translation and Its Place within Translation Studies – A Theoretical Discussion. Meta. 61(3):692-708.

- Maas, Utz and Wunderlich, Dieter (1976): Pragmatik und sprachliches Handeln. Mit einer Kritik am Funkkolleg „Sprache“ [Pragmatics and Linguistic Action. With a Critique of the Funkkolleg «Language»]. Frankfurt am Main: Athenäum.

- Mossop, Brian (2016): ‘Intralingual translation’: a desirable concept? Across Languages and Cultures. 17(1):1-24.

- Nord, Christiane (1989): Loyalität statt Treue. Vorschläge zu einer funktionalen Übersetzungstypologie [Loyalty Instead of Fidelity. Proposals for a Functional Translation Typology]. Lebende Sprachen. 24(3):100-105.

- Nord, Christiane (2011): Funktionsgerechtigkeit und Loyalität. Theorie, Methode und Didaktik des funktionalen Übersetzens [Functional Appropriateness and Loyalty. Theory, Method, and Didactics of Functional Translation]. Berlin: Frank & Timme.

- Paulien, Jon (1992): Eine Auslegung der Symbolik in der Offenbarung [An Interpretation of the Symbolism in the Book of Revelation]. In: Frank B. Holbrook, ed. Symposium über die Offenbarung. Einführende und exegetische Studien, Band I. Old Columbia Pike: Biblical Research Institute, 61-80.

- Prunč, Erich (2005): Translationsethik [Translation Ethics]. In: Peter Sandrini, ed. Fluctuat nec Mergitur. Translation und Gesellschaft. Festschrift für Annemarie Schmid zum 75. Geburtstag. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 165-195.

- Reiss, Katharina and Vermeer, Hans J. (1984/1991): Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie [Towards a General Theory of Translational Action: Skopos Theory Explained]. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Robinson, Douglas (2003): Becoming a translator: An introduction to the theory and practice of translation. London: Routledge.

- Saussure, Ferdinand de (1967): Grundfragen der allgemeinen Sprachwissenschaft [Fundamental Issues of General Linguistics]. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Searle, John R. (1969): Speech Acts. An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Seel, Olaf I. (2020): Orality, easy-to-read language intralingual translation and accessibility of cultural heritage for persons with cognitive and learning disabilities: the case of Greek oral history testimonies. Bridge: Trends and traditions in translation and interpreting studies. 1(2):18-46.

- Seel, Olaf I. (2021): How Much “Translation” Is in Localization and Global Adaptation? Exploring Complex Intersemiotic Action on the Grounds of Skopos Theory as a Conceptual Framework. IJTIAL. 3(2):1-15.

- Snell-Hornby, Mary (1988): Translation Studies. An Intergrated Approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Stolze, Radegundis (1992): Hermeneutisches Übersetzen. Linguistische Kategorien des Verstehens und Formulierens beim Übersetzen [Hermeneutic Translation. Linguistic Categories of Understanding and Formulating in Translation]. Tübingen: Narr.

- Toury, Gideon (1980): In Search of a Theory of Translation. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Volkova, Tatiana and Zubenina, Maria (2015): Pragmatic and sociocultural adaptation in translation: Discourse and communication approach. Skase, Journal of Translation and Interpretation. 8(1):89-106.

- Zehtsen, Karen (2007): Beyond Translation Proper—Extending the Field of Translation Studies. TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction. 20(1):281-308.

List of tables

Table 1

Contrastive analysis 1

Table 2

Contrastive analysis 2

Table 3

Contrastive analysis 3

Table 4

Contrastive analysis 4

Table 5

Contrastive analysis 5