Abstracts

Abstract

It seems that, for various reasons, indirect translation still occupies a marginal role in Translation Studies (see Pięta 2014) and it has not asserted itself as a research field in its own right. This paper discusses the role of indirect translation and mediating languages in translating children’s literature. The reasons for indirect translations in the Croatian context are explained. The process of indirect translation is investigated within the theoretical background of retranslation. Indirect translation is exemplified by Arnold Lobel’s story The Surprise (from Frog and Toad All Year), a story which has been translated into Croatian through the medium of German. The reasons for indirect translation are investigated as well as the effects of indirect translation on the final translated text. The article examines signals of foreignisation and domestication in the target text and the extent to which they can be attributed to German as the mediating language and German culture as the mediating culture.

Keywords:

- indirect translation,

- mediating languages,

- children’s literature,

- Arnold Lobel,

- Frog and Toad

Résumé

Il semble que, pour diverses raisons, la traduction indirecte occupe toujours un rôle marginal au sein des études de traduction (voir Pięta 2014) et ne s’est pas affirmée comme un domaine de recherche à part entière. Le présent article traite du rôle de la traduction indirecte et des langues médiatrices dans le cadre de la traduction de la littérature pour enfants. Il propose des arguments en faveur de la traduction indirecte dans le contexte croate. Le processus de traduction indirecte est analysé sous l’angle théorique de la retraduction. La traduction indirecte est illustrée par l’exemple de l’histoire d’Arnold Lobel intitulée The Surprise (tirée du livre Frog and Toad All Year), traduite en croate par le biais de l’allemand. Les motifs de la traduction indirecte ainsi que ses effets sur le texte final sont expliqués. On se penche sur les signaux d’étrangéisation et de domestication dans le texte cible, en examinant dans quelle mesure ils peuvent être attribués à l’allemand en tant que langue médiatrice et à la culture allemande comme culture médiatrice.

Mots-clés :

- traduction indirecte,

- langues médiatrices,

- littérature jeunesse,

- Arnold Lobel,

- Frog and Toad

Resumen

Por diversos motivos, la traducción indirecta todavía ocupa un lugar marginal en los estudios de traducción (ver Pięta 2014) y no ha conseguido establecerse como un campo de investigación de manera consistente. Este artículo aborda el rol de la traducción indirecta y los lenguajes de mediación a la hora de traducir literatura infantil. En este trabajo se explican las razones por las que realizar traducciones indirectas en el contexto croata y se investiga el proceso de traducción indirecta dentro del marco teórico de la retraducción. La traducción indirecta se ejemplifica a partir de la historia de Arnold Lobel The Surprise en Frog and Toad All Year, que se ha traducido al croata a partir del alemán. El estudio analiza los motivos de la traducción indirecta así como sus efectos en el texto final. También se estudian las señales de extranjerización y domesticación en el texto final y el grado en el que estas pueden ser atribuidas al alemán como lenguaje de mediación y a la cultura alemana como la cultura de mediación.

Palabras clave:

- traducción indirecta,

- lenguajes mediadores,

- literatura infantil,

- Arnold Lobel,

- Frog and Toad

Article body

1. Introduction

Arnold Stark Lobel (1933-1987) was a prolific illustrator and author of children’s books who won several notable awards,[1] but was not always recognised during his life. Besides being known for his Fables (1980), he is remembered by teachers and scholars alike for his Frog and Toad series, which consists of the following titles: Frog and Toad Are Friends (1970), Frog and Toad Together (1972), Frog and Toad All Year (1976) and Days with Frog and Toad (1979). Each of the four books from the series contains five easy-to-read, short and humorous stories about the humble adventures of Frog and Toad, two anthropomorphised characters who are best friends. Except for the mentioned characteristics, the series is often discussed in regard to some of its most prominent features such as style, setting and the topic of friendship.

The Frog and Toad stories are well-written I-Can-Read books (Lynch-Brown and Tomlinson 1993/2008: 40). Lobel wrote the stories in simple and short sentences that are easy to read and suitable for beginner readers (see Galda, Sipe, et al. 2013: 337), but they can also be considered as “primers for many kinds of literacy, including analytical [and] critical reading from a variety of theoretical perspectives” which makes them also suitable for adult beginners in the analytical reading of children’s literature (Rosenberg 2011: 72). The timeless setting of the stories is a “child’s paradise,” pastoral and Victorian, self-contained and secure, without intrusions from the outside world and adults (Silvey 2002: 270), an environment conveyed through both text and pictures.

The main topic of the series is a sincere and gentle friendship between two male characters with complementary personality traits. According to Silvey (2002: 270), the main reason why the Frog and Toad stories are considered classics is “because they exemplify friendship, acceptance, and reliability.” Frog can be considered the more adult of the two because he is more practical and rational than Toad (Rosenberg 2011: 84), but can sometimes seem bossy. Complementarily, Toad is more passive and pessimistic and needs guidelines (Silvey 2002: 271).

Recently, the topic of friendship in the Frog and Toad series has been discussed through a scope which includes the author’s biographical elements. Rosenberg (2011: 84-85) argues that Lobel’s background and later-in-life confirmed homosexuality supports homosexual readings of the stories, but since “there is no overt sexuality in any of the stories” concludes that the more appropriate description of Frog and Toad’s friendship is simply homosocial.[2]

On the other hand, Lobel’s works can frequently be found on lists of gay-friendly picture books (see, for example, Barbara Bader’s review [2015] or James Marshall’s obituary for Lobel [1988] in the Horn Book Inc. journal).

Lobel is relatively unknown to the wider Croatian audience as there is no direct translation of Lobel’s work into Croatian. However, he is relatively often mentioned in academic circles where his works are included in overviews of Anglophone children’s literature, or in connection with teaching English to young learners (see Narančić Kovač and Likar 2001).

Interestingly, the only Croatian translation of Lobel’s work is an indirect translation from English via German and is connected to educational settings: the Croatian translation of the story The Surprise from the book Frog and Toad All Year (1976) appeared in various literary readers.

That is why the following article will discuss indirect translation and the role of the mediating language[3] in translating children’s literature from English into Croatian, based on the example of Lobel’s story. The text will be analysed with respect to the translation strategies used, the signals of foreignisation and domestication in the target text (Venuti 1995) and the extent to which German, as the mediating language, and German culture, as the mediating culture, have contributed to the final product.

2. Indirect translation

In spite of its huge and sometimes crucial influence in literary and cultural mediation,[4] indirect translation (ITr) has largely been marginalised in Translation Studies, mostly due to prejudices and misconceptions caused by demands of faithfulness and closeness to the source text (Pięta 2014; Rosa, Pięta, et al. 2017; Li 2017). This may be one of the reasons why it has not become established as a research field in its own right.

One of the reasons may lie in the lack of comprehensive Anglo-American research on the use of English as a main mediating language in today’s world (see Ringmar 2012). Besides, such translations are discouraged by the UNESCO recommendations (1976), suggesting a translation should be made from the original work, with exceptions only where absolutely necessary, probably anticipating possible poor translations from the source language (SL) into the mediating language. Another, perhaps more significant reason, has to do with the fact that “research in Translation Studies has been marked by reductionist, if not imperialistic approaches” (Pięta 2019: 28). It predominantly concerns translations from, into or between the so-called (hyper)central languages (Heilbron 1999). On the other hand, ITr is typically assumed to occur in communication between peripheral languages (Heilbron 1999), including scholars linked to languages like Catalan, Chinese, Dutch, Hebrew, the Scandinavian languages, etc. (Ringmar 2012), that is, occurring much less commonly and therefore less studied linguistic combinations (see Pięta 2019: 28).

According to Kittel and Frank (1991: 3), ITr is “based on a source (or sources) which is in itself a translation into a language other than the language of the original, or the target language.” Gambier (1994) speaks of a translation of a translation, or a “new translation” into a target language where there already exist one or more versions of the same work (see also Gambier 2003: 49). For Toury (2012: 82) ITr involves “translating from languages other than the ultimate source language.” According to Ringmar (2007), ITr also frequently highlights the power relations between cultures/languages, showing that the mediating language is, as a rule, a dominant language, whereas the target language (TL) is dominated. The Croatian context is no exception. The examples of ITr with English as the source language which we were able to trace have shown that some indirect translations reached Croatian readers through German, Italian or Russian. We will attempt to explain the reasons for those indirect translations.

2.1. Indirect translation in the context of children’s literature in Croatia

Although the majority of literary works originally written in English were translated directly into Croatian, the fact that some Anglophone authors reached Croatian readers through mediating languages cannot be overlooked. Historically and geographically, strong socio-political links can be observed between Croatian and two other languages: German and Italian. The former influenced Croatian mostly because Croatia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from the 16th century until the end of the First World War. Towards the end of the 18th century, German became the dominant language of communication throughout the monarchy, as well as the official language of education and science (see Glovacki-Bernardi and Jernej 2004). In the Croatian parts of the Habsburg Empire, German was used as a second language by a number of educated Croatian native speakers. In the same way, Italian was used as a second language in the Croatian littoral regions of Dalmatia and Istria, which had been under the rule of Venice, and later of the Kingdom of Italy. Glovacki-Bernardi and Jernej (2004: 203) refer to this phenomenon as “civic bilingualism.” These were most probably the reasons why a number of literary works by Anglophone authors reached Croatian readers through their German or Italian translations, since the majority of educated Croatian native speakers were fluent in either German or Italian. Besides, German translations of some well-known Anglophone authors, such as William Shakespeare or Daniel Defoe, seem to have had an easier way reaching Croatian readers than their originals, particularly in the 18th and 19th century. For example, Shakespeare’s works reached Croatian readers through Schlegel’s German translations/adaptations of his works. In a similar way, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe first appeared in Croatian as a translation of the German adaptation of Campe’s novel Robinson der Jüngere, zur angenehmen und nützlichen Unterhaltung für Kinder, from 1779. Its Croatian translation, by Antun Vranić, was published in 1796 under the title Mlajši Robinzon: iliti jedna kruto povoljna i hasnovita pripovest za detcu od J. H. Kampe (Majhut 2012). The translator dedicated the book to children and their teachers and educators. The text follows the German text and is structured in dialogical form, containing a few didactic poems written in octosyllabic verse.

The practice of ITr continued in the 20th century. According to Špoljarić (2007-2008), during the first half of the 20th century, Viktor Dragutin Sonnenfeld, a renowned translator and philosopher, who is known to have translated from German, also published novels in the series Biblioteka Hrvatskog lista[5] starting in 1936. His translations included works by Arthur Conan Doyle, Zane Grey, Tex Harding, Philip McDonald, Edward Philips Oppenheim and Edgar Wallace. Since there is no mention that he was a translator from English, it is reasonable to assume the titles by the mentioned Anglophone authors which appeared in this series were translated from German.

The following example of ITr is important in children’s literature and Anglophone-Croatian literary connections. The classic of American children’s literature The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by Lyman Frank Baum was originally published in 1900. As a result of a remarkable reception by both critics and readership, thirteen more sequels were published by the year 1920. The first translation of Baum’s novel into Croatian appeared in 1963. Although seemingly culturally significant, it actually represents an indirect translation of the adaptation of Baum’s novel from Russian. The novel was translated into Russian and adapted by Alexander Volkov[6] and subsequently rendered in Croatian by Slobodan Glumac.[7] The translation can be found in the catalogue of the Zagreb City Libraries under the heading of Russian literature. The first translation from English was published only 14 years later, in 1977, followed by numerous new editions and (re)translations (for details see Kujundžić 2017).

Another series of English texts which reached Croatian readers as ITr were four books from the Little Women series by Louise May Alcott (1868; 1886; 1871; 1880). This time the mediating language was Italian. The translations were published in 1968 in Zagreb, but the target language was Serbian.[8] At the time, it was not unusual to publish translations of books in Serbian and then distribute them in libraries throughout the country.

As can be seen from these examples, besides direct translations from English into Croatian, there is also a history of indirect translations through mediating languages, especially German and Italian.

2.2. The Surprise in Croatian translation

Although an indirect translation by definition, the Croatian translation of the story The Surprise is a result of a rather simple and transparent relay of the German text translated by Karin Schreiner in 2001.[9] The story was first translated into Croatian in 1993 and published in a reader for lower primary school (Lazić and Zalar 1993). It appeared again in the same context 6 years later (Kolanović, Mihoković, et al. 1999). In the meantime, the same text reappeared in 1995 in a set of proposed texts for kindergarten teachers (Anonymous 1995). In all of the above-mentioned cases, the text is the same and is, somewhat surprisingly,[10] an indirect translation from English into Croatian via German.

Blanka Pašagić[11] translated the story from German, which is clearly stated in the paratext next to the translator’s name, under the published text in the reader (1999). That information appeared only in the reader published in 1999, although the exact same text had been published twice before, in 1993 and in 1995. In both paratexts Arnold Lobel is written as the author of the original text, but there is no mention of the German translator.

The reasons for translating the text into Croatian were most probably educational, with the purpose of compiling a literary reader for third grade primary pupils. Sadly, Blanka Pašagić passed away and therefore we can only speculate about the reasons for this particular indirect translation. However, according to the customary practices regarding compilations of literary readers for pupils in lower primary grades in Croatia towards the end of the 20th century, one of the two following scenarios is highly probable. Firstly, several prolific translators and children’s literature authors often published in popular children’s journals. The editors and/or authors of literary readers would then choose freely among the texts published in those journals and include them in their readers if they found the texts suitable—topic-wise or in any other way. Secondly, it is also possible and highly probable that a colleague, a teacher or a friend prompted the translation of a certain literary text deemed suitable after having used it in the classroom and then, through professional and private contacts, the text made its way into a literary reader.

The authors/editors of the literary readers in question were thus not always aware of the origin of some of the texts they published, since the author’s or translator’s names did not regularly appear in the readers. In this particular case, the translator herself and the fact that she translated the text from German were signals possibly leading to a false conclusion—namely that the text originally belonged to German literature. Once the translation entered a corpus of texts for literary readers, it was simply reused in a different reader, such as the one published in 1999 (Milković 2023: 154).

3. Methodology

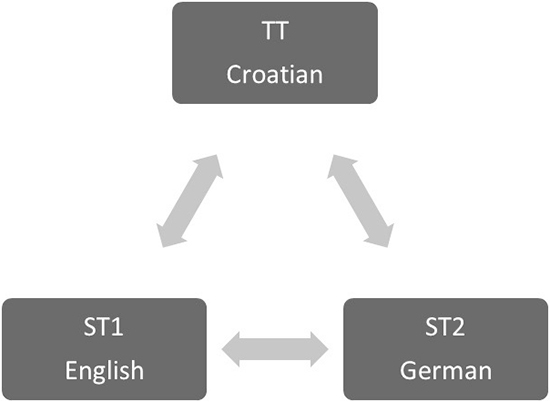

In order to avoid misunderstandings and terminological discrepancies, the terms source language 1 (SL1) and source text 1 (ST1) are used for the language of the original (English), source language 2 (SL2) and source text 2 (ST2) for the mediating language/text (German) and target language (TL) and target text (TT) for the final translation, in our case Croatian. The process of translating from SL2 to the TL is referred to as indirect translation (ITr) (see Špirk 2014).

We first compared the ST2 to the original (ST1) to establish that the translated text (ST2) was longer. Consequently, the same was established for the TT. Having taken this as the starting point for our analysis, we conducted a detailed analysis of linguistic and culture-related features of the ST2 and the TT and compared them to the ST1.

Translation strategies were broadly analysed in the following two categories:

-

characters’ names

-

other text characteristics of the source text (ST1) and the German translation (ST2), including the use of short sentences, simple vocabulary and repetition.

Next to the connections and strategies observed in the target text (TT) in relation to the German text (ST2), the analysis also required constant comparison with the source text in English (ST1), in order to find possible explanations for the strategies used in the TT and the extent to which the ST1 reflected on the target text. Thus, the analysing process in each of the categories required constant comparison of all the three texts involved (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The process of analysing translation strategies in the target text which is the product of an indirect translation

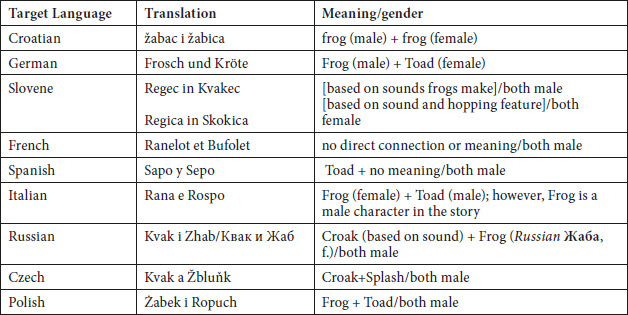

Furthermore, in the analysis of the first category (translation of characters’ names), the methodology and classification often used in similar research in children’s literature translation was used (Nord 2003; Fernandes 2006) along with Van Coillie’s classification of translations strategies (2014).[12] The findings were then compared to available translation solutions in other languages (French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Czech, Polish and Slovene).

The second category required a partial immersion in detailed translation-oriented text analysis adapted for the purpose of this particular text. The analysis focused on the following intratextual factors of the source-text analysis suggested by Nord (2005: 93-131): subject matter (focus on the title and the topic), content, microstructure of text composition (organisation of sentences and clauses), lexis and sentence structure (construction and complexity of sentences). The strategies were partly modified and adapted to suit the analysed texts.

When looking into the extent to which the translation strategies used can qualify as foreignisation or domestication (Venuti 1995), a model based on Franco Aixelà’s (1996) taxonomy was used (see Milković 2023: 162).

4. Results

4.1. Characters’ names

In the ST1 there are two male characters: Frog and Toad.[13] Their names are common nouns, turned into proper names by capitalisation. Although they are both anthropomorphised amphibians, there are biological differences between them. Frogs are smaller, with legs longer than their body, which are normally used for leaping. Toads, on the other hand, have shorter legs and prefer to crawl rather than jump. Also, a frog’s skin is slimier and smoother, while toads have drier skin covered with warts.

In ST2, Frosch and Kröte are the exact/literal translations of their names in ST1, based on the biological differences between the two animals and according to the grammatical gender in German. Der Frosch is a masculine noun, while die Kröte is feminine, which results in a gender change for the latter character (Toad) in ST2. While making sure that the translation preserves the biological characteristics of the two characters, a shift in gender is introduced. In ST1, both characters are male/masculine, which is supported by the illustrations. On the other hand, ST2 uses Lobel’s original illustrations showing two male characters, whereas in the text Frog is male, and Toad is female, possibly creating some confusion for the reader.

The Croatian translation (TT) of ST2 relies on the fact that Frosch is a male character and is thus translated as žabac (a male frog). In the same way, Kröte is translated as žabica, which denotes a little female frog. This is again a simple translation strategy, but apparently the translator’s goal was to preserve the male-female equivalence rendered in ST2. In addition to this gender change, in both cases the function of the nouns has been altered, since both žabac and žabica have been turned into common nouns. Possible reasons for such a change might lie in the fact that, while in German all common nouns are capitalised, in Croatian, capitals are only used for proper nouns. Not being aware of the ST1, it seems that the Croatian translator did not recognise that Frosch and Kröte are not common, but proper nouns in ST2. On the other hand, had the translator realised that those were in fact the characters’ names, she might have resorted to a different translation strategy since the Croatian words for both frog and toad are feminine nouns.[14] This could have resulted in a different translation strategy since the translator would have had to be more creative in inventing two male names if the goal was to preserve this feature of the ST1.

Table 1

Translation of characters’ names in several languages

As can be seen from Table 1, the same gender shift that occurred in the German and Croatian translations is noticed in the Italian translation, but here the female form for frog (Ital. rana, f.) became a male proper name (Rana, m.). The French, Spanish, Russian, Czech and Polish translations resorted to different translation strategies (that is, invention and onomatopoeia), in order to remain true to the ST1. In Slovene, two translations of the story are available, the first one with two male characters, relying on the onomatopoeic words imitating the sounds frogs and toads produce in Slovene (Slo. rega, kvak) in creating two male names (Regec, Kvakec). In the second example, the translator relied on the sound (Slo. rega) and the noun for hopping or jumping (Slo. skok), which resulted in female names for both characters (Regica, Skokica). Accordingly, this version contains new illustrations showing Frog and Toad as female characters.

4.2. Text characteristics

As established earlier, the ST1 consists of short sentences, it uses simple vocabulary and relies on repetition. An analysis and close reading of the story reveals that those features are used with a purpose and are further discussed in the categories of subject matter, content, text composition, lexis and sentence structure.

4.2.1. Subject matter and content

The title of the story in ST1 is The Surprise, perfectly announcing the topic of the story: the two friends want to surprise each other by raking the leaves from one another’s lawn. But, typically for October, by the time they reach their homes the leaves have been blown everywhere again. Consequently, they never see how clean their own lawn was after raking, but are convinced the other one will be happy and surprised to see their lawn has been cleaned.

The story takes place in October, which is clearly stated in the first sentence of ST1, ST2, and the TT. It is impossible to fathom why the title in ST2 is expanded to Herbstüberraschung (Autumn/Fall surprise) and why this additional explanation is employed, since it is clearly stated from the beginning (both ST1 and ST2) when the story happens. Interestingly, the Croatian translation omits the season from the ST2 title and gives the exact translation of the title as given in ST1: Iznenađenje (Surprise).

A more significant change can be detected in both ST2 and the TT, leading to a possible difference in reading and understanding the topic in both translations. As mentioned above, ST1 is a story about two male friends wanting to do something nice for one another, although this requires substantial physical effort. However, the change of gender occurring in the translation of names in ST2 and the TT results in a possible change of topic. Since the story now deals with a male and a female character in ST2 and TT, it is not necessarily about friendship anymore, but possibly about courtship. On the other hand, as Lobel’s private life may have influenced the homosexual interpretation of the relationship between the two main characters, it is also possible that, to avoid possible connotations or allusions to homosexuality that were hardly deemed appropriate for children readers almost 30 years ago, especially in the largely conservative culture and educational context of the TT, the gender shift caused by the change of names was welcomed as an appropriate solution. However, it is more probable that the text was simply translated in the most efficient way from German and that the Croatian translator was not aware of the male-female shift that had occurred in the translation from English to German.

4.2.2. Text composition

In the following stage, text composition is investigated. The analysis of the text’s microstructure encompasses the organisation of sentences and clauses, lexis and sentence structure. Additionally, the construction and complexity of sentences are analysed. The results are presented with the focus on repetition and rhythm, the use of the past tense and translation inaccuracies.

4.2.2.1. Repetition and rhythm

Lobel’s use of repetition and rhythm in ST1 helps create the characters and their world—a specific structure preserved in the ST2. This is achieved through the use of the same verbs describing the activities Frog and Toad do and by preserving the sentence structure of the original wherever possible. However, in the TT, the translator does not pay attention to these features. It seems that the translator intentionally avoided repetition, looking for words that could replace the verbs in ST1/ST2, probably supposing the text would be richer if synonyms were used instead of repetition (see examples 1 and 2).

2)

Toad ran through the high grass so that Frog would not see him.

Lobel 1976: 45, our underlininga)

Kröte läuft durch das hohe Gras, damit Frosch sie nicht sieht.

[Toad runs through the high grass so that Frog does not see her.]

Lobel 1976/1981: 45, translated by Schreiner, our underliningb)

Žabica pojuri kroz visoku travu da je ne primijeti žabac.

[Toad dashes through the high grass so that Frog does not notice her.]

Lobel 1976/1999: 20, translated by Pašagić, our underliningFor the same reason, the Croatian translation resorts to addition/expansion and longer phrases, even though the ST2 is true to the original regarding this feature, too (see example 3).

The third feature causing a change in rhythm is the use of compound and complex sentences instead of short ones and linking them with conjunctions (see examples 3 and 4). As a result, the Croatian text loses its specific melody, especially when read aloud or used as reading practice with young beginner readers.

3)

Soon Toad’s lawn was clean. Frog picked up his rake and started home.

Lobel 1976: 48, our underlininga)

Bald ist Krötes Rasen sauber. Frosch nimmt seine Harke und geht nach Hause.

[Soon Toad’s lawn is clean. Frog picks up the rake and starts home.]

Lobel 1976/1981: 48, translated by Schreiner, our underliningb)

Ubrzo je žabicin travnjak blistao od čistoće. Žabac naprti na leđa grablje i pođe svojoj kući.

[Soon Toad’s lawn was clean and shiny. Frog packed the rake on his shoulder and started home.]

Lobel 1976/1999: 20, translated by Pašagić, our underlining4)

I will rake all the leaves that have fallen on his lawn. Toad will be surprised.

Lobel 1976: 42, our underlininga)

Ich harke die Blätter zusammen, die auf Krötes Rasen gefallen sind. Kröte wird staunen!

[I will rake the leaves that have fallen on Toad’s lawn. Toad will be surprised.]

Lobel 1976/1981: 42, translated by Schreiner, our underliningb)

Pograbljat ću lišće koje je popadalo na žabicin travnjak. Kako li će se samo začuditi kad vidi da je sve počišćeno!

[I will rake the leaves that have fallen on Toad’s lawn. How surprised Toad will be when she sees everything has been cleaned!]

Lobel 1976/1999: 20, translated by Pašagić, our underliningExample 4 illustrates another change in the microstructure of the text that creates the specific rhythm of ST1. In ST2 the word all is omitted from the sentence. Accordingly, the word is not translated into the TT. This omission does not affect the understanding of the text but could be seen as a small cog in the stylistic wheel of rhythm. However, when combined with the following sentence in the TT, which is expanded and complex, the tone and style of the TT have obviously changed in comparison to ST1.

There are other instances of word or sentence omission (examples 5, 6 and 7). Three sentences from the original text have been omitted in ST2 and, consequently, in the TT as well. A comparison of the German and Croatian text has shown that the same sentences are left out in both texts. As those sentences do not appear in ST2, it can be assumed that the Croatian translator did not consult the original English text.

5)

Frog worked hard.

Lobel 1976: 486)

Toad pushed and pulled on the rake.

Lobel 1976: 487)

It [the wind] blew across the land.

Lobel 1976: 50Example 8 is an interesting instance of combined omission and addition: an entire word phrase was restructured. First, ST2 used einschlafen [to fall asleep] instead of the phrase go to bed from ST1. In the TT, the verb is simply translated from ST2 (Cro. zaspati). As a direct consequence of this change, there is no longer need for the phrase they each turned out the light, omitted in ST2 and in the TT. However, in ST2 the adjective happy was expanded and translated into besonders glücklich und zufrieden [particularly happy and satisfied], emphasising both Frog and Toad had a reason to be happier than usual. This meaning is lost in the TT, since the Croatian translator omitted the reason why they fell asleep so happy and satisfied. In this case, the TT apparently followed ST2 in translating the phrase, but omitted the word besonders. It can be concluded that although the TT can be traced back to ST2, the Croatian translator did not feel obliged to translate every single word, but was inclined to create what she deemed appropriate for the Croatian readers, not being aware of the rhythm of the original English text.

8)

That night Frog and Toad were both happy when they each turned out the light and went to bed.

Lobel 1976: 53, our underlininga)

An diesem Abend schlafen Frosch und Kröte besonders glücklich und zufrieden ein.

[In the evening Frog and Toad fall asleep particularly happy and satisfied.]

Lobel 1976/1981: 53, translated by Schreiner, our underliningb)

Te su večeri žabac i žabica zaspali sretni i zadovoljni.

[That evening Frog and Toad fell asleep happy and satisfied.]

Lobel 1976/1999: 21, translated by Pašagić, our underlining4.2.2.2. Use of tenses

In the original, Lobel uses the simple past tense to tell the story. According to Martin (1986: 74), “narratives concern the past.” The past tense as a convention of narratives is adopted at a very early age (Applebee 1978) and is often used when sharing past experiences, such as telling a story. By using past tenses in ST1, Lobel tells a story about friendship and puts the illustrations in the background of the story—the accompanying illustrations do not convey any new meaning to the story, thus the focus is on the verbal text. ST2 is also accompanied with the same illustrations as ST1 and illustrations tend to have “a present-tense quality” (Pullman 1989: 167). Thus, when the story starts with the sentences Es ist Oktober. Die Blätter sind von den Bäumen gefallen. Sie liegen auf der Erde. [It is October. The leaves have fallen off the trees. They are lying on the ground.], the “on the scene narrator” of the text (Lathey 2003: 234) and the reader of the story find themselves immediately in the illustration, surrounded by fallen leaves.

ST2 includes a combination of the German present (Ger. das Präsens) and past tense (Ger. das Perfekt), whereas the TT resorts to the perfective form of the verbs, denoting an action that has been completed, but in their present form. This is made possible by the feature of Slavic languages where verbs often have two aspects—the imperfective, standing for processes and the perfective one, for completion. The Croatian translator makes abundant use of this strategy and skilfully avoids the use of the Croatian equivalent of the English simple past tense (Cro. perfekt). Thus, he took is not translated as uzeo je (Cro. uzeti; uzeo je = Eng. take; he took), but the perfective aspect of the verb in the present is used instead (Cro. uzme). Similarly: gledati-pogleda, misliti-pomisli, trčati-potrči, juriti-pojuri, grabljati-pograblja.

In Croatian, this form is referred to as the historical or narrative present. It is used in narration in Standard Croatian to retell an action which took place in the past. It can also be referred to as relative present, as it denotes past actions and has a stylistic value of live retelling (Katičić 1981: 5), adding dynamics to the story. Having in mind that the TT does not include illustrations but only the verbal story, we can conclude that the Croatian translator wanted to tell the story in the past tense, but was prompted by the present tense in the ST2. The obvious choice was the use of the historical present, which denotes past actions but offers immediacy and emotional emphasis.

4.2.2.3. Inaccuracies in the TT

To conclude this short analysis, a few possible inaccuracies in the TT need to be mentioned. There are two expressions which can be characterised as inaccurate translations. Lobel uses the term closet—this is where Toad keeps his rake. The German translator decides to replace closet with Keller [cellar] and the same word is used in the Croatian text (Cro. podrum). The example may also be seen as a culture-specific item. In ST2, the translator decided that in German-speaking cultures rakes are kept in cellars rather than in closets. Thus, the item was translated by using the domestication strategy (Franco Aixelá 1996). There was no need to apply a translation strategy during the translation of the text in the Croatian language and culture, since rakes are also often kept in cellars in Croatia. A typical family house can contain a cellar, which can be used for storing garden tools, especially in the countryside.

Another inaccuracy regards the word lawn (Ger. Rasen; Cro. travnjak) which is inaccurately translated into Croatian as meadow (Cro. livada) on two occasions, signalling that the translator was possibly not aware of the difference in meaning between lawn and meadow.

5. Conclusion

With our analysis of the Croatian translation, we have attempted to discover possible reasons for indirect translation, the translation strategies used and, consequently, find out what effects they had on the target text.

As mentioned earlier in the text, there is a long history of indirect literary translation in Croatia, mostly due to its geopolitical, linguistic and literary connections to neighbouring countries. In the 20th century, most indirect translations came into existence out of convenience. We believe this is also the case with the Croatian translation of The Surprise from German, supported by the possible connection to the educational context and the appropriateness of the text for educational purposes.

The translation strategies detected in the process of this particular case of indirect translation were analysed having in mind the interconnectivity and the sequence of texts: from the English original (ST1), through German translation (ST2) into Croatian (TT). The analysis focused on characters’ names and text characteristics.

Due to the domestication of names in the TT, through which proper nouns were changed into common nouns, a gender change of the characters also occurred. This seems to be a common issue as it occurs in the translations of the story into Italian, German and Slovene. However, the change in gender has further consequences as it inevitably changes the topic of the story causing a shift from friendship to courtship. In this case, the shift occurred in the German translation and was simply conveyed in the Croatian text, too.

An analysis of text composition and its microstructure revealed changes of style. Lobel’s recognisable style of simple and short sentence, repetition and rhythm is preserved in ST2. However, in the TT, the translator avoids repetition, uses synonyms, longer phrases and expands sentences which results in complex structures and the loss of Lobel’s style.

The educational purpose of the text left an imprint on the TT. It is possible that the translator avoided repetition of the same words and used synonyms in order to expand the vocabulary used in the story. Such educational inferences in translations of children’s literary classics are common in the Croatian educational context in order to create as appropriate a text as possible, but as a consequence leaving out important literary qualities (see Kujundžić and Milković 2021). In this case, next to the loss of a certain style, the TT also lost the topics of friendship and humour in the text due to domestication strategies and changes made in ST2, and added domestication in the final transfer to TT. It seems that, with each translation, the text moved further away from its original form, style and purpose.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1. Corpus of Lobel’s works (originals and translations)

Lobel, Arnold (1976): Frog and Toad All Year. New York: HarperCollins Children’s Books.

Lobel, Arnold (1976): Les Quatre saisons de Ranelot et Bufolet. (translated from English by Adolphe Chagot). Paris: L’école des loisirs.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/1981): Frosch und Kröte bei jedem Wetter [Frog and Toad in any weather]. (translated from English by Karin Schreiner). Reinbek bei Hamburg: Carlsen Verlag.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/1983): Regica in Skokica [Frog and Toad]. (translated from English by Petra Vodopivec) Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/1999): Iznenađenje [Surprise]. (translated from German by Blanka Pašagić). In: Dubravka Kolanović, Davorka Miholović and Ivo Zalar, eds. Hrvatska čitanka 3, čitanka za 3. razred osnovne škole [Croatian reader 3, reader for the 3rd grade of primary school]. Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 20-21.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/2000): Regec in Kvakec. Za vse čase [Frog and Toad. For all times]. (translated from English by Petra Vodopivec). Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/2001): Sapo y Sepo todo el año [Frog and Toad all year]. (translated from English by Nuria Molinero). New York: Scholastic.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/2001): Kvak i Zhab kruglyy god (Квак И Жаб Круглый Год) [Frog and Toad all year round]. (Translated from English by Yevgeniya Kanischcheva [Евгения Канищева]). Москва: Розовый жираф.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/2016): Żabek i Ropuch. Przez cały rok [Frog and Toad. Throughout the year]. (translated from English by Wojciech Mann). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie.

Lobel, Arnold (1976/2018): Kvak a Žbluňk od jara do Vánoc [Frog and Toad from spring to Christmas]. (translated from English by Eva Musilová). Praha: Albatros.

Appendix 2. Other indirect translations from English to Croatian

Alcott, Louise May (1868/1968): Devojčice [Piccole donne/Little girls]. (translated from Italian by Jugana Stojanovi). Zagreb: Epoha.

Alcott, Louise May (1886/1968): Deca gospođe Džo [I ragazzi di Jo/Jo’s Boys]. (translated from Italian by Mara Krmpotić). Zagreb: Epoha.

Alcott, Louise May (1871/1968): Dečaci [Piccoli uomini/Little Men]. (translated from Italian by Mira and Emilija Bruneti). Zagreb: Epoha.

Alcott, Louise May (1880/1968): Devojčice rastu [Piccole donne crescono/Little girls grow]. (translated from Italian by Jugana Stojanović). Zagreb: Epoha.

Volkov, Alexandre Melentyevich (1939/1946): Čarobnjak iz Oza [Волшебник Изумрудного города/The Wizard of Oz]. (translated from Russian by Slobodan Glumac). Novi Sad: Budućnost.

Notes

-

[1]

Among other awards, Lobel won the Caldecott Medal in 1981 (Fables), Caldecott Honor in 1971 and 1972 (Frog and Toad are Friends) and Newbery Honor Award in 1973 (Frog and Toad Together).

-

[2]

The concept of homosociality describes and defines social bonds between people of the same sex. A popular use of the concept is found in studies on male friendship, male bonding and fraternity orders. It is also frequently applied to explain how men, through their friendships and intimate collaborations with other men, maintain and defend the gender order and patriarchy (Hammarén and Johansson 2014). For a more complex and dynamic view of homosociality, see Kosofsky Sedgwick (1985).

-

[3]

Piȩta’s terminology (2019) is used throughout the article.

-

[4]

The Croatian example is by no means an isolated case, since many scholars report an important role of indirect translations in their own culture, as in the example of Hans Christian Andersen’s tales which reached the Chinese readership through indirect translations and greatly influenced Chinese literature and culture (Li 2017).

-

[5]

Hrvatski list [Croatian Journal] was a daily paper published in Osijek from 1920 to 1945. Between 1936 and 1945. the paper occasionally published popular titles by Croatian and foreign authors.

-

[6]

See Appendix for the bibliographic information of indirect translations from English to Croatian.

-

[7]

Slobodan Glumac (1919-1990) was a Yugoslav journalist, translator and screenwriter.

-

[8]

In the former Yugoslavia (1945-1991), two of the official languages spoken in the Socialist Republics of Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro were Croato-Serbian and Serbo-Croatian. With the fall of the communist regime and the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, the Croatian language became the official language in Croatia, whereas Serbian became the official language of Serbia. The status of the two languages depended on the number of speakers of the former or the latter in the respective republics (the language had to be spoken by a majority of 70% of the population to become the official language).

-

[9]

See Appendix for references to Lobel’s works (originals and translations).

-

[10]

The surprise for scholars lies in the fact that in the 1990s English-Croatian literary connections were well established (for more information about cultural and literary connections with Anglophone cultures see Narančić Kovač and Milković 2009) and that the great majority of Anglophone children’s literature classics available in Croatian had been translated directly from English.

-

[11]

Blanka Pašagić (1948-2017) was a Croatian author and translator of children’s books. She mostly translated from German and French into Croatian.

-

[12]

Van Coillie (2014: 125-129) distinguishes ten different strategies in the translation of characters’ names: non-translation (reproduction, copying), non-translation plus additional explanation, replacement of a personal name by a common noun, phonetic or morphological adaptation to the target language, replacement by counterpart in the target language (exonym), replacement by a more widely known name from the source culture or an internationally known name with the same function, replacement by another name from the target language (substitution), translation of names with a particular connotation, replacement by a name with another or additional connotation and deletion.

-

[13]

There is no doubt that both characters are male as is proven in the illustrations accompanying ST1 and ST2, but not in TT, since there are no illustrations.

-

[14]

Frog is žaba (f.) and toad is žaba krastača (f.), which emphasises that its body is covered with warts (kraste).

Bibliography

- Anonymous (1995): Proza: odgojno-obrazovni rad [Prose: reader in education]. Osijek: Centar za predškolski odgoj.

- Applebee, Arthur (1978): The Child’s Concept of Story: Ages Two to Seventeen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bader, Barbara (2015): Five gay picture-book prodigies and the difference they’ve made. Hornbook. Consulted on January 20, 2022, https://www.hbook.com/?detailStory=five-gay-picture-book-prodigies-and-the-difference-theyve-made.

- Fernandes, Lincoln (2006): Translation of names in children’s fantasy literature: Bringing the young reader into play. New Voices in Translation Studies. 2:44-57.

- Franco Aixelá, Javier (1996): Culture-specific items in translation. In: Román Alvarez and M. Carmen-África Vidal, eds. Translation, Power, Subversion. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 52-78.

- Galda, Lee, Sipe, Lawrence R., Liang, Lauren A. and Cullinan, Bernice, eds. (2013): Literature and the Child. Eighth edition. Wadsworth: Cengage Learning.

- Gambier, Yves (1994): La retraduction, retour et détour. Meta. 39(3):413-417.

- Gambier, Yves (2003): Working with relay: An old story and a new challenge. In: Luis Pérez González, ed. Speaking in Tongues: Language across Contexts and Users. València: Universitat de València, 47-66.

- Glovacki-Bernardi, Zrinjka and Jernej, Mirna (2004): On German-Croatian and Italian-Croatian language contact. Collegium antropologicum. 28(1):201-205.

- Hammarén, Nils and Johansson, Thomas (2014): Homosociality: In between power and intimacy. SAGE Open. 4(1):1-11.

- Heilbron, Johan (1999): Towards a sociology of translation. Book translations as a cultural world-system. European Journal of Social Theory. 2(4):429-444.

- Katičić, Radoslav (1981): Kategorija gotovosti u vremenskom značenju glagolskih oblika [The category of completion of temporal meaning in verb forms]. Jezik. 29(1):3-13.

- Kittel, Harald and Frank, Armin Paul (1991): Introduction. In: Harald Kittel and Armin Paul Frank, eds. Interculturality and the Historical Study of Literary Translations. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 3-4.

- Kolanović, Dubravka, Mihoković, Davorka and Zalar, Ivo (1999): Hrvatska čitanka 3, čitanka za 3. razred osnovne škole [Croatian reader 3, reader for the 3rd grade of primary school]. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

- Kosofsky Sedgwick, Eve (1985): Between men: English literature and homosocial desire. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kujundžić, Nada (2017): The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in Croatian: Picturebook adaptations and translations. XI Congreso internacional ANILIJ / XIth ANILIJ International Conference. Granada, Spain.

- Kujundžić, Nada and Milković, Ivana (2021): Reading Winnie-the-Pooh in Croatian primary schools. In: Jennifer Harrison, ed. Positioning Pooh: Edward Bear after One Hundred Years. Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 120-147.

- Lathey, Gillian (2003): Time, narrative intimacy and the child: Implications of the transition from the present to the past tense in the translation into English of children’s texts. Meta. 48(1-2):233-240.

- Lazić, Dubravka and Zalar, Ivo (1993): Hrvatska čitanka 3, iz književnosti za 3. razred osnovne škole [Croatian reader 3, in literature for the 3rd grade of primary school]. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

- Li, Wenjie (2017): The complexity of indirect translation: Reflections on the Chinese translation and reception of H. C. Andersen’s tales. Orbis Literarum. 72(3):181-208.

- Lynch-Brown, Carol and Tomlinson, Carl M. (1993/2008): Essentials of Children’s Literature. Sixth Edition. Boston: Pearson.

- Majhut, Berislav (2012): Fragments from Mlajši Robinzon (1796). Libri & Liberi. 1(1):105-128.

- Marshall, James (1988): Arnold Lobel. The Horn Book Inc. Consulted on January 20, 2022, https://www.hbook.com/story/arnold-lobel.

- Martin, Wallace (1986): Recent Theories of Narrative. Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press.

- Milković, Ivana (2023): Prijevodi dječje književnosti kao (među)kulturni potencijal: književnost u hrvatskim čitankama za niže razrede osnovne škole [Translations of Anglophone literature as an (inter)cultural potential: literature in Croatian readers for lower primary school]. Zagreb: Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb.

- Narančić Kovač, Smiljana and Likar, Danijel (2001): Reading authentic stories in English as a foreign language with seventh graders. In: Yvonne Vrhovac, ed. Children and Foreign Languages III. Zagreb: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, 149-167.

- Narančić Kovač, Smiljana and Milković, Ivana (2009): English and Croatian literary and cultural connections in the first Croatian children’s magazine. Književna smotra. 4(154):111-128.

- Nord, Christiane (2003): Proper names in translations for children: Alice in Wonderland as a case in point. Meta. 48(1-2):182-196.

- Nord, Christiane (2005): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam/New York: Routledge.

- Pięta, Hanna (2014): What do (we think) we know about indirectness in literary translation? A tentative review of the state-of-the-art and possible research avenues. In: Ivan Garcia Sala, Diana Sanz Roig, and Bozena Zaboklicka, eds. Traducció indirecta en la literature catalana. Barcelona: Punctum, 15-34.

- Pięta, Hanna (2019): Indirect translation: Main trends in practice and research. Slovo.ru: Baltic accent. 10(1):21-36.

- Pullman, Philip (1989): Invisible pictures. Signal. 60:156-186.

- Ringmar, Martin (2007): “Roundabout routes.” Some remarks on indirect translations. In: Francis Mus, ed. Selected Papers of the CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2006. Consulted on 7 February 2022, https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/files/ringmar.pdf.

- Ringmar, Martin (2012): Relay translation. In: Yves Gambier and Luc Van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies. Volume 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 141-144.

- Rosa, Alexandra Assis, PIĘTA, Hanna and Bueno Maia, Rita (2017): Theoretical, methodological and terminological issues regarding indirect translation: An overview. Translation studies. 10(2):113-132.

- Rosenberg, Teya (2011): Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad Together as a primer for critical literacy. In: Julia Mickenberg and Lynne Vallone, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature. New York: Oxford University Press, 71-91.

- Silvey, Anita, ed. (2002): The Essential Guide to Children’s Books and Their Creators. Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Špirk, Jaroslav (2014): Censorship, Indirect Translation and Non-translation: The (Fateful) Adventures of Czech Literature in 20th-century Portugal. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Špoljarić, Marijana (2007-2008): Legat Viktora D. Sonnenfelda u Gradskoj i sveučilišnoj knjižnici Osijek [Bequest of Viktor D. Sonnenfeld at the City and University Library Osijek]. Glasnik Društva knjižničara Slavonije i Baranje [Bulletin of the Librarians’ Society of Slavonia and Baranja]. XI-XII:1-2.

- Toury, Gideon (2012): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Revised edition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Original edition, 1995.

- Unesco (1976): Recommendation on the Legal Protection of Translators and Translations and the Practical Means to improve the Status of Translators. Consulted on February 22, 2022, https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-legal-protection-translators-and-translations-and-practical-means-improve-status.

- Van Coillie, Jan (2014): Character names in translation: A functional approach. In: Jan Van Coillie and Walter P. Verschueren, eds. Children’s Literature in Translation: Challenges and Strategies. London and New York: Routledge, 123-140.

- Venuti, Lawrence (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London and New York: Routledge.

List of figures

Figure 1

The process of analysing translation strategies in the target text which is the product of an indirect translation

List of tables

Table 1

Translation of characters’ names in several languages