Abstracts

Abstract

In this article, we investigate journalist-translators’ strategies in dealing with English-language embedded social media quotes (ESMQs) in Norwegian and Spanish online news texts. Embedded social media quoting is a relatively new, but fast-growing phenomenon, which has yet to receive much scholarly attention. A few possible reasons for the (non-)translation of ESMQs in their surrounding main texts have been suggested in the hitherto scant literature, but one important hypothesis has not yet been introduced, namely that journalist-translators’ assumptions regarding the degree of English proficiency in their readers might influence their decisions regarding whether to translate (and how to translate). In this article, we present a comparison of the (non-)translation of 120 ESMQs in Norwegian vs. Spanish online news texts, which shows that there are in fact no significant differences in the rate of non-translation of these quotes, despite the fact that Norway and Spain are countries where English proficiency is assumed to be high vs. low, respectively. This means that assumed proficiency in the source language does not play the expected role in guiding journalist-translators’ decisions in our study, except if one can say that non-translation is chosen for two different reasons in the two groups: 1) a high degree of faith in the English proficiency of readers (in the Norwegian case), and 2) a low degree of confidence in one’s own English proficiency leading to translation avoidance (in the Spanish case). We conclude that qualitative research looking into various groups of journalist-translators’ motivations for (non)translation is needed.

Keywords:

- news translation,

- journalators,

- translingual quoting,

- English,

- embedded social media quotes

Résumé

Dans cet article, nous examinons les stratégies utilisées par les journalistes-traducteurs en rapport avec la langue anglaise, à travers les citations des médias sociaux (ESMQs) intégrées dans les textes d’actualités en ligne norvégiens et espagnols. Les ESMQs sont un phénomène relativement nouveau, mais en croissance rapide, qui n’a pas encore reçu beaucoup d’attention de la part des chercheurs. Quelques raisons possibles pour la (non-)traduction des ESMQs dans leurs textes principaux environnants ont été suggérées dans la littérature jusqu’ici peu abondante à ce sujet, mais une hypothèse importante n’a pas encore été introduite, à savoir que les suppositions des journalistes-traducteurs concernant le degré de maîtrise de l’anglais chez leurs lecteurs pourraient influencer leurs décisions concernant l’opportunité de traduire (et comment traduire). Dans cet article, nous présentons une comparaison de la (non-)traduction de 120 ESMQs dans des textes d’actualités en ligne norvégiens et espagnols, qui montre qu’il n’y a en fait pas de différences significatives dans le taux de non-traduction de ces citations, malgré le fait que la Norvège et l’Espagne sont des pays où la maîtrise de l’anglais est censée être, respectivement, élevée ou au contraire faible. Cela signifie que la maîtrise supposée de la langue source ne joue pas, dans notre étude, le rôle attendu pour guider les décisions des journalistes-traducteurs, sauf si l’on peut dire que la non-traduction est choisie pour deux raisons différentes dans les deux groupes : 1) un haut degré de confiance dans la maîtrise de l’anglais de la part des lecteurs (dans le cas norvégien), et 2) un faible degré de confiance dans sa propre maîtrise de l’anglais conduisant à éviter la traduction (dans le cas espagnol). Nous concluons qu’une recherche qualitative examinant les motivations de divers groupes de journalistes-traducteurs pour la (non)traduction est nécessaire.

Mots-clés :

- traduction journalistique,

- journalistes-traducteurs,

- citations translingues,

- anglais,

- citation de médias sociaux intégrée

Resumen

En este artículo investigamos las estrategias que utilizan los periodistas-traductores para las citas de redes sociales integradas (ESMQ, según sus siglas en inglés), en textos periodísticos en línea en noruego y español. El ESMQ es un fenómeno relativamente nuevo que, a pesar de su uso cada vez más extendido, aún no ha recibido mucha atención. En los pocos artículos sobre el tema, se mencionan algunas de las razones de la (no)traducción de los ESMQs en los textos en los que se encuentran integrados pero no se menciona la hipótesis de que haya periodistas-traductores que se planteen traducir o no (o cómo traducir) según el supuesto nivel de conocimiento de inglés de sus lectores. En este artículo comparamos la (no)traducción de 120 ESMQs en noruego y español en textos periodísticos en línea, demostrando que, de hecho, no hay diferencias significativas en la cantidad de citas que no se traducen, a pesar de que se asume que en Noruega la competencia del inglés es alta y en España baja. Esto significa que en nuestro estudio una supuesta competencia en la lengua de partida no es el elemento decisivo en la toma de decisiones de periodistas-traductores, con la excepción de que la no-traducción se elige por dos razones distintas en los dos grupos: 1) un alto grado de competencia en inglés por parte de lectores (en el caso noruego), y 2) un bajo grado de confianza en la propia competencia de inglés, lo que lleva a evitar la traducción (en el caso español). Al final abogamos por un estudio cualitativo sobre las motivaciones que llevan a los periodistas-traductores a la (no)traducción.

Palabras clave:

- traducción de noticias,

- perioductor/periodistas-traductores,

- citas translingües,

- inglés,

- citas de redes sociales integradas

Article body

1. Introduction

In the last couple of decades, social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, have become increasingly important as news sources for journalists the world over. Content posted on such platforms is nowadays frequently quoted in news texts, and when the source text (ST) quote is in a language other than the language of the news text, it is often, but not always, translated. The practice of quoting in translation has recently been given the label translingual quoting, defined as “the sub-process of news-writing by which utterances from sources are both quoted and translated” (Haapanen and Perrin 2019: 15), a double task that is mostly undertaken by the journalists themselves (Hernández Guerrero 2020: 378).

While there is abundant research on the use of social media in news production and dissemination (for example, Broersma and Graham 2012; 2013; Artwick 2013; Hedman and Djerf-Pierre 2013; Moon and Hadley 2014; Paulussen and Harder 2014; Canter 2015; Barnard 2016; Canter and Brookes 2016; Santana and Hopp 2016; Gulyas 2017; von Nordheim, Boczek, et al. 2018; Willnat and Weaver 2018), the ubiquitous phenomenon of translingual quoting in digital news texts is so far surprisingly underresearched. One notable exception is a recent article by Hernández Guerrero (2020) on the translation into Spanish of English-language tweets on the Universo Trump [Trump Universe] blog published by the Spanish digital newspaper El País.[1] In this article, the author draws attention to the fact that translingual social media quotes may be represented in news texts in two basic ways: either without their source text counterpart, in which case readers may not even be aware that what they are reading is a translation, or with the source quote embedded in the news text, that is visible to the reader, and accompanied (mostly) by a translation somewhere in the body of the text: “the original text and its translation are shown in the same space as if it were a bilingual edition” (Hernández Guerrero 2020: 382). Hernández Guerrero (2020) proceeds to analyse the translation procedures used in both types of quotes, finding that the overwhelming tendency was for the journalist-translator to paraphrase them or to leave them untranslated. The frequent use of embedded social media quotes (henceforth ESMQs) as a predominantly graphic element for illustrative purposes (Broersma and Graham 2013: 450) is suggested as the likely reason for the relatively large number of untranslated tweets.

In Hernández Guerrero’s study (2020), the source language of the ESMQs was English, which, as we know, is not just any language, either from a global perspective or a translational one. Despite the difficulties in obtaining precise numbers, English is generally assumed to be the world’s largest language in terms of its number of native and non-native speakers combined.[2] Still, Hernández Guerrero does not delve into the idea that the special position of English in the world might have something to do with journalists’ choices to translate or not to translate these ESMQs: given that English is such a widely understood language, and the prototypical function of translation is to render something that is not understandable to a given group of recipients, is it not fair to assume that journalists’ assumptions regarding their readers’ degree of English as a second language (ESL) proficiency will play a role in their decisions whether to translate or not, and even how to translate?

We wanted to investigate this further by studying similarities and differences in translational patterns in regard to such ESMQs for two different language pairs, English/Norwegian and English/Spanish, chosen because of a well-documented, clear contrast in the degree of ESL proficiency between speakers of Norwegian in Norway (higher degree) and speakers of Spanish in Spain (lower degree) (see section 3.1.1.). If ESMQs are left untranslated more frequently in the Norwegian news texts than ESMQs in the Spanish texts, then this could be an indication that an assumed ability to understand the ESMQ plays at least some role in influencing which translation procedures are chosen. In the study we are presenting here, we examined 60 English-language ESMQs in three Norwegian digital newspapers, two tabloids and one broadsheet, and 60 English-language ESMQs in two Spanish digital newspapers, one tabloid and one broadsheet (see section 3.1.2.). We looked at whether the ESMQs were translated or not, and if they were translated, we looked at whether they were fully or only partially translated, and which microlevel procedures (literal translation, calque, domestication, or interpretation) were used. In addition to presenting quantitative overviews of the main results, we also looked more closely at individual examples in order to show how the procedures come across in actual texts. In the discussion, we evaluate whether our hypothesis—that an assumed degree of ESL proficiency determines whether ESMQs are translated, and how they are translated—has been confirmed, and outline the most likely factors to have influenced the choice of both macro- and microlevel strategies and procedures.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The use of social media as source in journalism

Journalists today are strongly expected to interact with online platforms in their production of news stories (for example, Broersma and Graham 2013; Hedman and Djerf-Pierre 2013; Barnard 2016; Willnat and Weaver 2018). The most frequently used platforms used by journalists are Twitter and Facebook (Santana and Hopp 2016). Barnard (2016: 196-198) lists eight different journalistic practices involving Twitter. Of these, six involve journalists actively participating on social media platforms, posting content and interacting with others (news dissemination/sharing information/retweeting; public note-taking/live-tweeting; public engagement/interacting with the public; development of journalistic meta-discourse/discussions of ethics and practices; other professional interactions; personal interactions).[3] The remaining two practices listed by Barnard are what could be called mining practices, that is, information collection and sourcing. Social media such as Twitter can function as a journalistic beat (Broersma and Graham 2012), traditionally understood as a topically more or less contained area for newsgathering (such as the police, courts of law or parliaments). In a social media context, it is understood as “a virtual network of social relations of which the journalist is a part with the purpose of gathering news and information on specific topics” (Broersma and Graham 2012: 405).

In 2012, Broersma and Graham referred to the practice of including tweets as quotes in newspaper reporting as a “new textual convention” (405). Today, this kind of practice, which can hardly be called new anymore (von Nordheim, Boczek, et al. 2018: 807), has recently seen an upsurge in research. Researchers have looked at the use of social media content, predominantly from Twitter, in, for example, British (Broersma and Graham 2012; 2013; Canter 2015; Canter and Brookes 2016), Dutch (Broersma and Graham 2012; 2013), Belgian (Paulussen and Harder 2014), German (von Nordheim, Boczek, et al. 2018) and US (Artwick 2013; Barnard 2016) newspapers. A main finding is that while there is considerable variation between countries (von Nordheim, Boczek, et al. 2018: 813; Willnat and Weaver 2018: 891), practices are becoming more similar in some regions (Gulyas 2017). Both tabloids and broadsheets (that is, “quality newspapers”) have been studied, and Broersma and Graham (2013: 453) found differences between popular and quality papers to the effect that the former sourced tweets more often than the latter. Social media quotes are used both in “hard” and “soft” news coverage (Paulussen and Harder 2014: 547), but more often in soft news (Broersma and Graham 2013: 453; von Nordheim, Boczek, et al. 2018: 812).[4] Both official sources and regular members of the public are quoted and of these, the former are found to be relied on more regularly than the “vox populi” (Broersma and Graham 2013: 457; Moon and Hadley 2014: 289; Paulussen and Harder 2014: 548; Wallsten 2015: 34). Social media quotes were found by Broersma and Graham (2013: 450-451) to have four different purposes in news articles: they are considered newsworthy in and of themselves (they trigger news stories), they illustrate—add flavour to—a larger story, they are standalone (for example, as “tweet of the day”) or “part of a question and answer exchange in the article.” Overall, Broersma and Graham (2013: 456) state that, “illustration was the most frequent function” in their material, consisting of articles drawn from British and Dutch tabloids and broadsheets.

2.2. Translation of ESMQs

With global news flows and social media, source material is increasingly in other languages (Haapanen and Perrin 2019: 15). And when incorporating this kind of material in their writing, the journalists themselves do the translations (Filmer 2014: 145; Hernández Guerrero 2020: 378). Often, however, journalists who translate for reporting have little or no formal training in the source language—they have what Filmer (2014: 145) characterises as a “do-it-yourself approach to language learning”—and mostly, they do not have formal training in translation. Filmer, who interviewed a number of British foreign correspondents in Italy, uncovered a dominant we-take-it-in-our-stride attitude among the journalists studied (2014: 146; see also Hannerz 1996: 120). One of her interviewees did point to potential problems with not having a formal background: “We are correspondents, we are not trained translators and if we do have the language it’s been learned in an informal way. Given the pressures of deadlines, the translation process is an informal one that is open to error” (Filmer 2014: 149). In light of these risks, several of Filmer’s interviewees report sometimes soliciting help from native-speaker colleagues or using native-speaker assistants (Filmer 2014: 145, 147).

2.2.1. News translation

The task these journalists perform is quite different from the most prototypical forms of translation, and one that they can certainly be said to be experts in (Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 59), that is pulling together various pieces of information from various sources, untranslated as well as translated, to create a new text in a process that has become known as transediting (Stetting 1989). The nature of this kind of translation has earned these journalist-translators a label that separates them from “regular” translators (and non-translating journalists), that is journalator (van Doorslaer 2012: 1049).

The main characteristics of the translation tasks carried out by journalators have been laid out by van Doorslaer (2012: 1047-1051) as being the following:

A traditional ST-TT relationship is rarely seen: One ST can be translated into many different TTs, and several STs can occur within or be “collapsed” into one TT.

Information in the ST is subject to radical selection and deselection decisions; partial translations get intermixed with the journalist’s original writing (see also Perrin and Ehrensberger-Dow 2012: 367).

The translation process is a mix of summarizing, paraphrasing, transforming, supplementing, reorganizing and recontextualizing.

The journalist’s main allegiance is to his or her reader; taking “into account the new circumstances of the target situation and audience … the journalator’s interventions simultaneously manifest characteristics of a translator, a communicator, a manipulator, a mediator and a transmitter” (van Doorslaer 2012: 1050).

In sum, “what matters most in news trans-editing is not ‘faithfulness’ or ‘equivalence’ but ‘rewriting’ by dint of various types of textual manipulation” (Chen 2009: 204). Of special relevance to the present project is van Doorslaer’s fourth point, which seems to support our hypothesis that readers’ ESL proficiency will play a role in decisions regarding whether or not to translate, and how to translate.

Holland (2013: 336-341) lists a number of constraints on news translation which are also likely to affect the target text in various ways:

Time pressure: journalists typically work under strict deadlines (“speed is part of the job” [Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 91])

Resources: these may differ between different news media

Differences in sociolinguistic conventions and target culture acceptability

The pervasiveness of English as a world language, which leads to a majority of the world’s news being produced in that language, creating an increasing translational load on journalists

When we consider ESMQs, the last point takes on an even broader significance than that envisaged by Holland in 2013. The growth of the convention of including such elements in news texts is more likely than not fuelled by the fact that English dominates the internet today (Bokor 2018), and by extension also has a considerable presence in social media. This means that English is a language that many readers across the world can, if not necessarily understand, at least recognise and relate to. Even when the language is not understood, the use of English-language ESMQs adds an international flavour to a story and creates a connection between the writer and their news organisation on the one hand and connotations of modernity, cosmopolitanism and attractiveness on the other (typically cited as connotations arising from use of English in the context of non-English languages and cultures, see Al-Naimat and Saidat 2019: 5).

2.2.2. Translation of quotes, including ESMQs

Quoting is an important sub-genre of newswriting. Referring to Bell (1991) and Cappon (1991), Chen (2009: 207) defines quotation thus: “Quotation, both direct and indirect … [is] concerned with what people say, such as announcements, statements, opinions, responses and criticisms.” Quotes “perform important functions in journalistic narration: they enhance the reliability, credibility, and objectivity of an article and characterize the person quoted” (Haapanen and Perrin 2019: 17). Using direct quotes, Haapanen and Perrin continue, can imbue a text with authenticity and liveliness (2019: 21) and give the journalist the possibility of creating and upholding a distance between themselves and the content of the quotation (Chen 2009: 208).

The translation of quotes from sources in news reporting—translingual quoting (Haapanen and Perrin 2019)—is a frequent occurrence. Studies that focus on quotations in translation are, however, few and far between. Available studies focus mostly on translations between English and Asian languages and Arabic, and on how ideology causes translational manipulation (Kuo and Nakamura 2005; Chen 2009; Matsushita 2020), sometimes to the effect that the same ST is translated completely differently by newspapers with different ideological leanings (Kuo and Nakamura 2005: 397). Zagood (2019) looks specifically at social media quotes from the perspective of the influence of ideology. The object of study is Donald Trump’s tweets, which are found to pose considerable challenges for journalist-translators on Arab online news websites. Drawing on Vinay and Darbelnet’s (1958/1995) model for analysing translation procedures, the author concludes that due to the journalists-translators’ ideological agency the translations of these tweets tend more towards the oblique than to the direct.

The only study to date (to our knowledge) that discusses not only social media quotes per se, but embedded social media quotes and their translation, is the one by Hernández Guerrero (2020) mentioned at the outset of this article. As stated, this study analyses tweets translated on the Universo Trump blog of the Spanish digital newspaper El País, and the focus of investigation is the procedures used when tweets are used as quotes in these news texts. In the sample analysed by Hernández Guerrero (2020: 382), there was a large predominance of cases where the original tweet was embedded, and in the sample analysed, the large majority of ESMQs were either left untranslated or paraphrased. The main function of the untranslated ones was said to be that of providing

additional information and support in the articles. Readers who know English read them and the tweets complement the information provided. When, on the contrary, readers do not know the language or have a very low level of proficiency and cannot understand the tweets then the tweets function as an informational design element.

Hernández Guerrero 2020: 386

In other words, ESMQs are seen to have a function vis-à-vis both types of audiences but function differently in the two cases.

In a minority of cases, literal translation was found to be used, sometimes with an unidiomatic TT as a result, sometimes not. Cases of the former, which Hernández Guerrero classifies as “mistakes” (2020: 386), are explained as a result of journalist-translators’ typical lack of formal translation training and/or translation competence, possible time pressure, and “the socio-cultural conditions in which translations are performed” (Hernández Guerrero 2020: 386).

3. Material and method

The present study is a product-oriented, descriptive (Toury 1995), more specifically descriptive-explanatory (Saldanha and O’Brien 2013: 50), comparative study of the translation of 120 English-language ESMQs in five newspapers (tabloids and broadsheets) in two different languages, Norwegian and Spanish, which aims to uncover whether or not they are translated and the procedures used to translate them.

3.1. Material and sampling

3.1.1. Language pairs

The language pairs English/Norwegian and English/Spanish were chosen because of the marked differences in ESL proficiency between Norway and Spain. Such differences in proficiency levels could be argued to explain any differences one might find regarding the use of (non-)translation strategies and translation procedures, since an assumed level of proficiency could potentially be one factor playing on the journalist-translator’s mind in the translation process.

Norwegian ESL proficiency is among the highest in the world. According to Education First’s (2019) English proficiency index, which ranks countries and regions by English skills, Norway has been among the top five in the world since 2011.[5] English is a core subject in school during all ten years of compulsory primary and lower secondary education, and the language is “everywhere” in Norwegian society. Popular culture—music, gaming, undubbed film and television—is an obvious space where this plays out (Jakobsen 2019: 2-3), but many types of workplace within, for example, academia and business are experiencing domain loss of Norwegian (Haberland 2005) with English becoming an increasingly common working language (Ljosland 2014; Sanden 2020). In Spain, ESL proficiency is among the lowest in the European Union. Although according to Eurostat, the EU’s statistical office, “[a]ll or nearly all (99-100%) primary school pupils in Cyprus, Malta, Austria and Spain learned English as a foreign language in 2018,”[6] reports from Education First (2019) indicate that Spain ranks 25th of 33 European countries, and 34th worldwide, in English proficiency. Furthermore, according to a 2021 survey carried out by the National Statistics Institute (INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística), only 15% of Spaniards feel confident in their English skills, while 75% confess to knowing little or no English.[7] Hernández Guerrero (2020: 386) concludes that available data on the ESL proficiency level in Spain “indicates that a significant proportion of readers cannot read … [untranslated] tweets.”

3.1.2. Newspapers and topic areas

The newspapers chosen were two Norwegian national tabloids, Dagbladet [The Daily Magazine][8] and Verdens Gang (VG) [Way of the World][9] as well as one national broadsheet, Aftenposten [The Evening Post]. For the Spanish part of the study, one Spanish broadsheet, El País [The Country][10] and one “tabloid-like” newspaper[11] (in the following referred to simply as “the (Spanish) tabloid”), El Confidencial [The Confidential],[12] were chosen. Some of these newspapers appear both in paper and online format. We accessed examples only from the online versions. Despite the fact that differences between “tabloids” and “broadsheets” have become more blurred in the last 25-30 years[13] (Alba-Juez 2017), not least as a result of newspapers’ move into a digital space, the decision to distinguish between them was based on a desire to create comparability with previous studies, which often do make this distinction (see section 2.1.). The choice is also justified in that the distinction is still possible to make: tabloids tend to emphasise soft news (especially from popular culture), broadsheets the opposite (Pugh 2011; Alba-Juez 2017), and are thus regarded as more “serious,” aiming at a readership who consumes less entertainment, but more objective information. In this regard, the Norwegian newspapers Dagbladet and VG are prime examples of tabloids, while Aftenposten, traditionally a broadsheet, remains so also in its online version, with more stories on high culture and art within the area of soft news, and more emphasis on politics and societal issues. In regard to the Spanish newspapers, the broadsheet and tabloid description is not applicable as the larger format ceased to exist some years ago. Today, most newspapers in Spain are published in the “tabloid” format (Armentia Vizuete 1992). However, in this study, where the broadsheet is synonymous with hard news, we chose to gather these Spanish examples from El País. El Confidencial, while not strictly a tabloid, publishes much more entertainment or soft news.

The reason for the difference in the number of newspapers for the two languages has to do with the topic areas chosen for this study which were 1) sports, 2) politics and 3) social/celebrity. These were chosen with the hard/soft news distinction in mind, to see whether this distinction could be argued to impact on choices made in the translation. The tabloid initially chosen for the Norwegian part of the study was Dagbladet, which turned out to have no examples of ESMQs in their politics articles. In order to be able to harvest examples in this category, Norway’s only other large, national tabloid, VG, was included in the study. The reason why Dagbladet could not be exchanged altogether for VG as a source of examples is that VG and the broadsheet Aftenposten collaborate on their sports news, meaning that many of the articles in this category contained the same ESMQs and the same translations of these. In turn, the dearth of large, national broadsheets in the small country of Norway necessitated the choice of Aftenposten.

3.1.3. Sampling

The examples were selected over a period of about ten months in 2020/2021. The fact that the selection process lasted for a relatively long time is accidental and not due to a lack of examples. Examples were generally abundant and easy to find. For each of the languages, 60 ESMQs and their (non-)translations were harvested, 30 from the tabloids (10 from each topic area) and 30 from the broadsheets (10 from each topic area), that is, 120 ESMQs altogether. The sampling was systematic: for each topic area, articles would be checked one by one, scanned for ESMQs and whenever one or more ESMQ was encountered, it would be included in the pool of examples. Some articles would contain more than one ESMQ, and in these cases, all the ESMQs in that article would be entered into the pool.

By contrast with many other studies on social media quotes, non-translated or translated, we did not focus on one or more specific platforms because we did not find that there was reason to think that quotes from different platforms would be translated in fundamentally different ways. The majority of the quotes nevertheless ended up being from Twitter. A couple were from Facebook (found in the Norwegian material) and the slightly newer messaging service Signal (found in the Spanish material), and a great deal were from Instagram, especially in the social/celebrity category.

3.2. Analytical procedure

Each ESMQ representation in the main text was initially classified as no translation, full translation (all of the content is somehow represented in the translation), or partial translation (some of the content is somehow represented in the translation). This is a somewhat more detailed scheme than that of Hernández Guerrero (2020), who does not distinguish between full and partial translation (her category “paraphrase” covers both). The reason why the full/partial distinction was a relevant category for the present study is because of the possibility that the journalator’s assumption of a high degree of English proficiency in readers might trigger not only more non-translation, but also more partial translation (than full translation). In considering whether or not a text should be classified as a full or a partial translation, it is important to note that we did not take into consideration emojis or instances of non-conventional use of punctuation (for example, double or triple exclamation or question marks). That is, if all the verbal text was represented in a given translation but not such symbols, it was nevertheless classified as a full (not a partial) translation.

For each fully or partially translated ESMQ, coupled pairs (Toury 1995: 79) were identified. A coupled pair—consisting of a replaced item in the ST and its replacement item in the TT—was, for the purpose of this analysis, further defined as co-extensive with the beginning and end of the use of one and only one translation procedure (examples are given in section 4.2. below). Each ESMQ and its associated translation might contain one or several coupled pairs.

Each coupled pair was classified as either literal translation, calque, domestication, or interpretation. The first two categories, literal translation and calque, were defined along the lines of Vinay and Darbelnet’s (1958/1995) model. That is, literal translation is a word-for-word translation that happens to result in an idiomatic TT because the source and target languages are similar enough for this to be possible in the given instance. Calque is also a word-for-word translation, but one that results in an unidiomatic TT, either on the syntactical or the lexical level or both. Note that these two categories (literal translation and calque) are subsumed under “literal translation” in Hernández Guerrero’s (2020) model, and that literal translations that result in a TT that does not quite conform to target language conventions (our calque) are given a negative characterisation by her, as “interference,” or “negative transfer” (Toury 1995: 274-279). Here, we wish to avoid such evaluation, especially since, in many languages—and this is very much the case for Norwegian—many calques from English are steadily working their way into the regular lexicon, gaining at least folk status as perfectly appropriate, both in original texts and in translated texts.

The categories of domestication and interpretation, in the present model, both refer to translations that are not word-for-word. Domestication involves linguistic shifts, either obligatory or non-obligatory ones (that is due vs. not due to differences between the linguistic systems of the source and target language; Vinay and Darbelnet 1958/1995). Non-obligatory shifts may also involve corrections of errors in the source. Crucially, however, in cases of domestication, the original, quoted source still comes across, in the TT, as the enunciator of the message. When the interpretation procedure is used, the shifts are, for a start, often greater (more in the direction of paraphrasing, summarising, etc.), but most importantly, the enunciator of the message is no longer the quoted source, but the journalator and/or the newspaper he or she represents. This manifests itself as shifts from direct to indirect quotation.

4. Analysis and findings

In this section, we present overviews of the number of full, partial and non-translations (“macrolevel analysis”) and of translation procedures used (“microlevel analysis”), in order to enable an overall comparison between the Norwegian and the Spanish results. In the microlevel analysis (section 4.2) examples of the different translation procedures from both parts of the corpus will be shown and discussed.

4.1. Macrolevel analysis: translation vs. non-translation

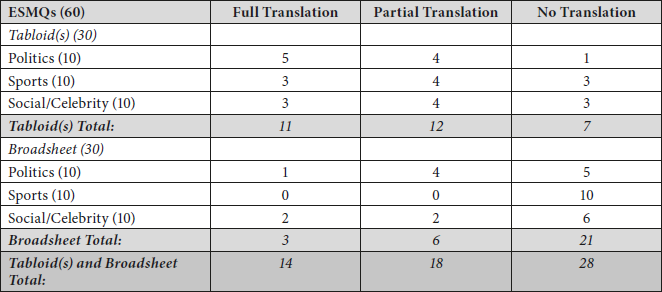

Table 1 below shows that approximately half of the 60 ESMQs in the Norwegian corpus were either fully or partially translated (32 ESMQs), while the other half (28 ESMQs) were not translated. The number of full vs. partial translations was more or less even.

Table 1

Macrolevel analysis of the Norwegian corpus

Furthermore, we see that the ESMQs in the tabloids were translated more frequently than those in the broadsheet: in the tabloids 23 of the 30 ESMQs were translated and only 7 were left untranslated, while in the broadsheet the result is almost the exact opposite. Here, only 9 of 30 ESMQs were translated, while 21 were left untranslated. When it comes to topic area, there is, within the tabloids, a more or less even distribution of full, partial and non-translation between the three topics (politics, sports and social/celebrity). Among the Norwegian broadsheet examples, the one striking finding is that none of the ESMQs in the sports category are translated at all. All 10 examples are left untranslated.

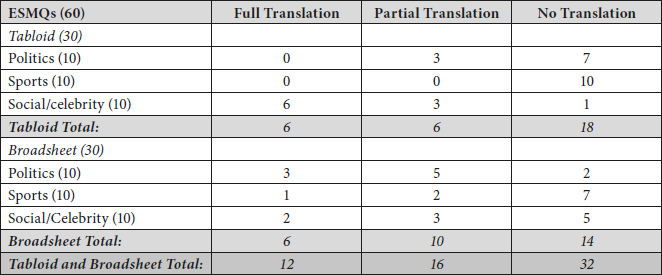

Table 2

Macrolevel analysis of the Spanish corpus

In Table 2, it immediately becomes clear that our initial hypothesis—that degree of journalator-assumed English proficiency among readers will (co-)determine whether an ESMQ will be translated—is not supported by the data in this study. Where we expected there to be less translation in the Norwegian corpus (due to high ESL proficiency) and more translation in the Spanish corpus (due to lower ESL proficiency), we see instead that the ratio of fully and partially translated vs. non-translated ESMQs in the Spanish corpus as a whole is more or less equal to that of the Norwegian corpus, with a weak tendency (perhaps too weak strictly speaking to be called a “tendency”) in the opposite direction in the Spanish case—towards non-translation (28 ESMQs are translated, while 32 are left untranslated).

This could be an indication that the prototypical, or core, function of translation—to render content understandable to a reader who does not know the source language (very well)—is not a major influencing factor in these translational processes and that general quoting practices and other factors are much more strongly at play in determining whether a translation is provided. This is something which will be discussed in more depth in section 5 below.

In the Norwegian corpus, we saw that the tabloids showed a pattern of employing more translation than the broadsheet. In the Spanish corpus, the pattern is again the opposite, even more distinctly so. Here, the tabloid leans more strongly towards non-translation (12 translated, 18 untranslated) than the broadsheet, where, in contrast to the Norwegian results, the numbers of translation vs. non-translation are more equal (16 translated, 14 untranslated). In the Spanish tabloid, the tendency towards non-translation is strongest in the politics category (3 translated vs. 7 untranslated ESMQs) and—especially—in the sports category, where none of the sampled ESMQs are translated. The results within the sports category (zero translated, 10 non-translated ESMQs) echoes the Norwegian results; however, in the latter, the same striking finding is located in the broadsheet part of the corpus. In the Spanish broadsheet, we also find a tendency towards a prevalence of non-translation in the sports category, although the tendency is not quite as strong as in the Norwegian corpus (3 translated vs. 7 non-translated ESMQs). The number of examples here is of course too low to enable us to draw any definite conclusions, but the results within the category of sports in the Spanish tabloid and broadsheet, and the Norwegian broadsheet, taken together, could indicate the presence of a specific quoting sub-practice within this particular topic area which is not local but shared across a larger geopolitical area.

4.2. Microlevel analysis: procedures

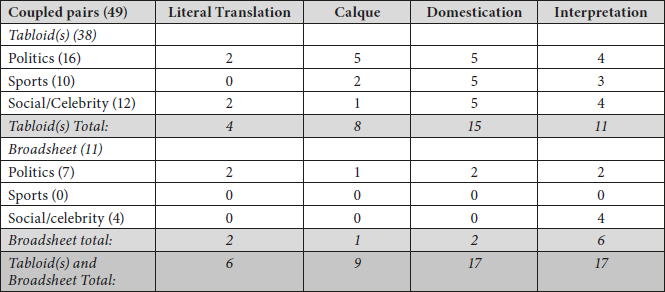

Table 3 shows the number of coupled pairs found within the 32 translated ESMQs in the Norwegian corpus, and which procedures the journalist-translators have used in translating them. The overall finding is that there is considerably less use of literal translation and calque than of domestication and interpretation. Of the 49 coupled pairs found in the Norwegian corpus, 15 were translated using the first two procedures, while 34 were translated using either the domestication or interpretation procedure.

Table 3

Translation procedures in the Norwegian corpus

Despite considerable typological similarity between English and Norwegian, literal translation—a strict word-for-word, structure-for-structure rendering of an ST item that does not result in an unidiomatic ST counterpart—is not a frequent occurrence. In the Norwegian corpus, translations occur slightly more frequently in the tabloids, in the politics and social/celebrity topic categories, than in the broadsheet, where they only occur in the politics category. The following example is a celebrity Instagram post in Dagbladet containing two items that are both translated literally in the body of the text (these are analysed as two coupled pairs rather than one because there is intervening text between them):

Here, both translations are obviously literal. What TT1 and TT2 also illustrate is the overall tendency to omit nonstandard punctuation in translation (here, the repetition of question marks and exclamation marks) and symbols (here, a heart emoji). As stated earlier, the fact that this is a general tendency in all the examples studied led to the decision to leave these out of consideration in this particular analysis. Another thing to note here is the addition of quotation marks in both TTs, which signals the use of direct quotation, meaning that the original source is allowed to retain the role as enunciator—to have a voice—in the new text.

As expected, some calques were found. In Norway, due to the prevalence of the English language in everyday life, code switching with English has become a very common occurrence both in speech and writing, and there is a growing use of calqued expressions, especially in young people’s language production (see Sunde and Kristoffersen 2018). And although no hard evidence of this has yet been produced, it is reasonable to believe that the tendency towards calquing from English into Norwegian is even greater when translation is involved because of the pressure of the ST on the TT (see the law of interference; Toury 1995). The 30 ESMQs in the tabloids presented 8 calques (the majority in the politics category), while the broadsheet Aftenposten only contained 1, again in the category “politics.” The broadsheet example is reproduced in Example 2 below, an ESMQ in the form of a tweet, posted as a response to France’s attempts at banning the wearing of the hijab in public by minors. The ST is partially translated in the surrounding text using several translating procedures; the replaced element of the coupled pair under discussion here, however, is “we are standing with you.”

“We are standing with you” is not a fixed expression in Norwegian; the replacing element, a direct translation — “vi står med dere” [we stand with you]—has a distinct unidiomatic ring to it and is thus analysed as a calque. The shift from gerund to simple present is, obviously, a domesticating move, but the main procedure used here is calque.

Domestication was found within all the topic areas in the tabloids, but (like literal translation and calque) only in the politics area in the broadsheet. The following coupled pair is a typical example of domestication in the Norwegian corpus; this fully translated ESMQ is extracted from the tabloid VG, from the topic area of “politics.”

In this example, the TT clearly renders Jarrett’s voice in the form of a direct quote (despite the lack of use of quotation marks). The domestication comes in the form of three minor shifts. The first and second of these shifts consist in the correction of a linguistic and a text-conventional error in the original tweet, respectively: “the incredibly seventeen year old” (which features an adverb where there should be an adjective, and is missing hyphenation between the three final words) is rendered correctly in Norwegian, as “den utrolige 17-åringen” [the incredible 17-year-old]. The third and final shift is due to the choice of the translator to adjust the phrase “may never” to its Norwegian, idiomatic counterpart “ville kanskje aldri” [would maybe never].

Interpretation was used in all three topic areas in the tabloids, and in the politics and social/celebrity categories in the broadsheet. Example 4 below is taken from Aftenposten, from the topic area “social/celebrity.”

This ESMQ is a post taken from pop artist Justin Bieber’s Instagram account containing Bieber’s take on a conflict between Taylor Swift and a representative from her previous record company, Scooter Braun, regarding contractual rights to reproduce Swift’s music. Clearly, this example verges on what some would not accept as a translation (see Valdeón 2015: 643-646), but it is clearly some kind of rendering of what Bieber said, albeit in a minuscule nutshell.

Even though the translation is much shorter than its ST counterpart, it could nevertheless be argued to render the full meaning of the ST—Bieber’s whole speech is indeed a defence of Braun—and it has therefore been analysed, here, as a full translation.

In the ST, Bieber is the enunciator; in the TT, however, it is the journalator’s voice that is foregrounded, channelling what Bieber has said, which further supports the classification of this procedure as interpretation.

Let us turn now to the Spanish findings.

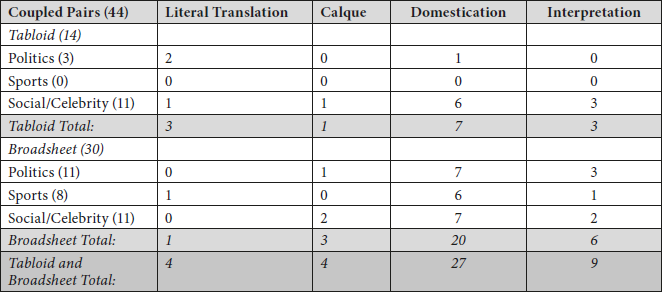

Table 4

Translation procedures in the Spanish corpus

An initial observation is that the number of coupled pairs identified in the Spanish corpus is quite close to the number of the coupled pairs identified in the Norwegian corpus (49 in the Norwegian vs. 44 in the Spanish corpus). Furthermore, the overall trend seems to be the same: there are considerably fewer literal translations and calques (13 altogether) than examples of domestication and interpretation (45 altogether). In fact, the contrast is more pointed here than in the Norwegian corpus.

In the Spanish corpus, literal translations occur slightly more frequently in the tabloid than in the broadsheet, which mirrors the Norwegian findings (although the numbers are too low, of course, to rule out the possibility of this being merely accidental). The largest number of literal translations in the Spanish corpus were found in the category “politics.”

In this example, a lengthy tweet by Boris Johnson is partially translated, reduced to a quotation of two lone words, which have been literally translated: “profundamente angustioso” [deeply distressing]. This kind of reductive approach seems, incidentally, to be a general strategy used by this newspaper; another example in the Spanish corpus contains a reduction of another lengthy tweet, in that case to one single word (“terroristas”).

In the Norwegian corpus there are nine examples of calque; in the Spanish, there is less than half that number, four in total. Of these four, one is found in the tabloid (in the social/celebrity category) and three in the broadsheet (in the categories “politics” and “social/celebrity”). This is the opposite finding from the Norwegian part of the study where the majority of calques were found in the tabloids.

“Worst shape” [peor forma] is analysed as a calque here given that the journalator’s word-for-word translation renders an unidiomatic form in Spanish. One might speculate that an idiomatic expression would not only have been much longer, but would not have mirrored the order of the speaker’s original words.

Domestication is by far the largest category in the Spanish corpus. Interestingly, the instances in the Norwegian and Spanish tabloids and broadsheets are flipped: in the Norwegian corpus there are more domesticated coupled pairs in the tabloid (15 examples vs. only 2 in the broadsheet) and in the Spanish there are more in the broadsheet (20 examples, vs. 7 in the tabloid). In the Spanish broadsheet, cases of domestication were divided fairly equally among all three topics, while most examples of domestication in the Spanish tabloid were found in the “social/celebrity” category.

In this example of domestication in the tabloid-like newspaper one can see the grammatical changes typical of this translation procedure: the possessive “whose plane” is replaced by a longer phrase, “el avión … en el que viajaba” [the plane … in which he was travelling]. There is also some explicitation, such as replacing “him” by “periodista” [journalist]. Furthermore, this example lays bare the typical intervention of some journalators. The quote begins with the addition “Como muchos otros” [as many others] (not present in the source text), which introduces a number of unspecified “others” in addition to the “we” that Boris Johnson is talking about in the source tweet, who are presumably the British. This strategy of adding information (sometimes collected from elsewhere), even as the source is still presented as the enunciator, occurs further on in the Spanish rendition with the addition of “Ryanair” to describe in greater detail the type of plane the protagonist of this news, the Belarusian journalist Roman Protasevic, was on—information that does not appear in the tweet in English.

While the Norwegian corpus showed a perfectly even distribution of domestication and interpretation overall (17 and 17), the Spanish corpus displays considerably fewer interpretations (9) than domestications (27). In the Norwegian corpus, the majority of the examples of interpretation are found in the tabloid, while in the Spanish corpus, they are found in the broadsheet. The following is an example of interpretation.

This is arguably a particularly complex example of interpretation as the source text, in this case, is not a statement made directly by an enunciator (which then, subsequently, “loses their voice” in translation, which would unambiguously make this a case of interpretation). Instead, it is in itself a quote. Thus, we have two enunciators in this tweet: the Taking the Initiative Party (TTIP), and the person quoting the TTIP. What the journalist-translator arguably does here is to directly quote the enunciator within the tweet. The enunciator of the tweet (quoted by the journalator in all of the other examples discussed in this article) is merely quoted indirectly, by virtue of the mere presence of the embedded tweet, which allows readers—at least those who are proficient in English—to infer that the journalist-translator is quoting the enunciator of the tweet. In this way, the voice of the author of the tweet is “taken over” by that of the journalator, making this a case of interpretation. Examples of this nature highlight the complexity of the ways in which information is typically disseminated today, both in non-translated and in translated texts, and illustrate the idea of “transediting” so often referred to in studies of journalistic translation. According to van Doorslaer, “the journalator’s interventions simultaneously manifest characteristics of a translator, a communicator, a manipulator, a mediator and a transmitter” (2012: 1050). Disentangling these roles and making sense of how they play out in actual texts is not an easy task, but it is nevertheless an important exercise insofar as imprecise understandings of them can have negative factual as well as ethical consequences.

5. Discussion

Van Doorslaer connects journalators’ interventionist role to the idea that their main allegiance is to their reader, taking “into account the new circumstances of the target situation and audience” (2012: 1050). In light of this assumed duty to take care of readers’ needs, it would be reasonable to think that paving the way for an actual understanding of the content of the various messages presented in a given news story would be given high priority. The overall result of this small-scale study—that English-language embedded social media quotes are not translated any more frequently in news stories in newspapers aimed at an audience that have lower proficiency in English—would seem to indicate that this is not necessarily the case. When it comes to the fact that many quotes indeed are translated, in both corpora, this could of course be due to the prototypical function of translation (to make content understandable); it could, however, simply be seen as an extension of general quoting practices: even when ESMQs in the target language are included in news articles, one still often sees use of paraphrase in the surrounding text. By paraphrasing and translating, journalists and journalators meld their own voices together with those of the quoted subjects, putting their own spin on the issues in question, overtly signalling their roles as mediators and communicators, establishing a relationship built on authority and trust vis-à-vis readers. And when it comes to the cases where there is no translation, we need look no further than to other, more general functions of (embedded) quotes such as enhancing the reliability, credibility and authenticity of the article (Haapanen and Perrin 2019: 17, 21), and graphic illustration (Broersma and Graham 2013: 456), to explain why journalators choose to include such quotes. Even when readers do not (fully) understand the meaning of the words in ESMQs, their use will give the impression of a journalist with “nothing to hide,” someone who is “playing with an open deck,” which readers will find reassuring; and the images, symbols, links and typographical elements in the ESMQ will in and of themselves trigger aesthetic and emotional responses in readers. This use of ESMQs might be due to a desire to break up a possible tediousness from the written word and fall in line with other aspects of the online medium. Already in 1992, Hurtado Santón, González López, et al. (1992: 82) stated that the use of Anglicisms in the Spanish press could be due to a desire to avoid monotony or even to surprise the reader.

Even in light of all this, the notion of ESL proficiency could still possibly play some kind of role in explaining the results of the macrolevel analysis. For a start, the high number of non-translations of English-language ESMQs, even in countries where ESL proficiency is low, could conceivably be due to something like a “Global-English effect”: the highly dubious, but nevertheless quite potent, myth that “everyone in the world knows English” might lead journalists in such countries to overestimate the degree of English proficiency in their readers. Another possibility is that the high rate of untranslated English-language quotes in the Norwegian as well as the Spanish corpus has different proficiency-related explanations in the two cases. Could it be the case that the reason why Norwegian journalators so often feel free not to translate is because they know that their readers are likely to understand the content of the quotes without translation, while Spanish journalators, belonging to the same, general ESL-proficiency category as their readers, avoid translating because they do not feel confident enough in English to undertake such a task? As pointed out by Holland (2013: 336-341), more and more news content everywhere is originally in English, something which imbues journalators with an increasingly heavy translational load. This load is bound to be experienced as heavier in countries where ESL proficiency levels are low to medium. This is perhaps a hypothesis worth pursuing, in the form of surveys and/or interviews with journalators themselves.

Other interesting findings on the macrolevel concern the differences in overall strategy use in tabloids vs. broadsheets and between topic areas. When it comes to the tabloid/broadsheet distinction, there was a distinct difference in translational practices between the two corpora. While a tendency towards more use of social media quotes in tabloids (than in broadsheets) has been recorded in the literature (Broersma and Graham 2013: 453), there was, in the Norwegian corpus, also significantly more translation than non-translation in the tabloid newspapers than in the broadsheet. In the Spanish corpus, the result was the opposite, which aligns itself with the findings in Broersma and Graham, where it was shown that in Britain and the Netherlands, “[t]he quality papers […] used tweets more as an illustration of news events or larger trends that were covered in either news reports, analysis, or background articles” (2012: 412). In light of the (currently weakened, of course) hypothesis that assumed ESL proficiency is an influencing factor in decisions regarding whether to translate or not, only the Norwegian result makes sense, since writers in tabloids are likely to work on the assumption of a readership with a less consistently high level of education (that is with “less good English”) than writers in broadsheets (see Chan and Goldthorpe 2007), implying that they would need more help in understanding the English in the ESMQs in the form of translation. But this, of course, does not explain the Spanish data at all. A more likely explanatory avenue to pursue here would be that there exists a pan-European convention shared by Spanish journalators (but not by the Norwegian ones), or that there are differences in institutional conventions or editorial policies either between different types of newspapers or just among newspapers generally (whether tabloid or broadsheet) in Norway vs. Spain (see Matsushita 2020: 158). To find out, a broader selection of newspapers in both categories would have to be studied, preferably in combination with qualitative studies into the editorial policies of the different newspapers.

As regards macrolevel differences according to topic area, there is one striking finding, namely the tendency not to translate ESMQs in news stories within sports sections. The tendency is slightly stronger in the Norwegian corpus, but nevertheless quite noticeable in the Spanish corpus, too. The number of examples at this level of the analysis is, as we pointed out, too low to be able to draw any definite conclusions, but it is still interesting to speculate that there might be something about that topic area that invites—across language areas—a lack of translation of ESMQs. A great number of articles on sports, at least in Norwegian newspapers, are about football (soccer), which at least in northern Europe has traditionally been dominated by English football. This has led to a situation where the English language is fairly ubiquitous whenever and wherever the sport is played, in English-speaking countries or outside. In fact, this sport has even been accused of being a considerable factor in causing the spread of English as a global language, and “football English” (Bergh and Ohlander 2020: 359) as a phenomenon in non-native-English-speaking countries has become an established concept. English, in this context, is a strong element in constructing authenticity and translation might conceivably ruin this perception of authenticity. It is even possible that seasoned fans might be offended if the language was translated for them, implying, as it might do, a lack of competence in the language and thus a reduced right to their in-group identity as a football fan.

On the analytical microlevel, where we looked at the distribution of the use of four different translation procedures, literal translation, calque, domestication and interpretation, individual numbers are too low to draw any conclusions, but we nevertheless allow ourselves to draw attention to at least some possible patterns. The main finding in both corpora is that there is considerably less use of literal translation and calque than of domestication and interpretation. These findings concur with those of Hernández Guerrero (2020: 387), who found that “paraphrase” (her term) is a dominant procedure.

The dearth of literal translation—defined quite strictly in our study as word-for-word translation that produces an idiomatic result in the target text—is easily explained as a result of the differences between the languages involved in the two different pairs: even though there are systemic similarities between English and Norwegian on the one hand and English and Spanish on the other, the differences are so great that literal translation cannot be upheld over larger stretches of text. The relatively low numbers of calque are perhaps slightly more surprising, especially in the Norwegian corpus, since English-based calque is strongly on the rise in Norwegian (Sunde and Kristoffersen 2018), which has created a higher degree of acceptability for this phenomenon, traditionally associated with “bad writing” and “bad translation.” This fact can, however, explain the somewhat higher numbers of calque in the Norwegian corpus than in the Spanish corpus. Spain is among the many countries that have reacted to the onslaught of English in the world in different ways. After years of journalists being accused of diluting Spanish by incorporating Anglicisms into Spanish newspapers, there have been concerted efforts to try to put a stop to this.[23]

As stated, both corpora showed a prevalence of domestication and interpretation. According to Bielsa and Bassnett (2009), domestication (which in their case refers to the larger, overall strategy and not to the more specific procedure as defined by us, and thus encompasses interpretation) is generally the most prevalent approach in news translation and so this finding, then, is hardly surprising. Domestication is a prevalent norm (Chesterman 1993) in translation generally, of course, not just in news translation, but journalist-translators are perhaps in its grip even more strongly than “regular” translators due to the expectation that they “take charge” of the issues they are reporting on, imbuing them with their own agency as writers.

As for the distribution of domestication vs. interpretation in the two corpora, there was far less domestication (as compared to interpretation) in the Norwegian corpus, than in the Spanish corpus. One possible explanation for this is that the greater English proficiency of Norwegian journalators gives them more confidence and freedom to “manipulate” the news, producing a higher number of interpretations. Some studies (not all) have shown that novice translators tend to stay closer to the source text than more experienced translators (see Płońska 2014: 70-72)—this is a tendency that could perhaps also transfer to the distinction between less and more linguistically confident journalators, explaining the reluctance of Spanish journalists to “throw themselves into the deep end.”

In the present corpora, all the various translation procedures were spread out across newspaper type (tabloid vs. broadsheet) and across topics in ways that could in some cases suggest some patterns, but the numbers are too low and these patterns are too unclear to warrant any further discussion.

6. Summary and avenues for further research

The overall conclusion of this study is that contrary to what we hypothesised at the outset, the fact that English is a language that many newspaper readers understand, and readers in some countries understand better than readers in other countries, is probably not a significant factor in determining overall ESMQ translation strategies (that is non-translation vs. translation). The only thing that might challenge this conclusion is if it turns out that the Norwegian and Spanish journalators refrain from translating (a considerable number of ESMQs) for two different reasons: the assumption of readership ESL proficiency and a lack of confidence in one’s own proficiency in English leading to a reluctance to translate, respectively. This could fruitfully be studied by means of qualitative methods where journalators are asked about their motivations for (not) translating.

Even if it turns out that ESL proficiency does have something to do with it, this would not be the only explanation, of course. Translation vs. non-translation of ESMQs is affected by a number of different factors that have to do with the general functions of quotes in news texts as producers of reliability, credibility and authenticity. Tweets or Instagram/Facebook posts constitute the visible presence of the source on the page and are able to fulfil these functions, whether they are translated or not. They can also work as illustrations breaking up the monotony of the text. When an ESMQ is translated, this is often a reflection of the customary blending of voices in news stories—journalators intertwining their own voices with those of their sources, thus appropriating a degree of control over the text and its content, ultimately for the benefit of the reader, who picks up that there is indeed a main voice in the story leading them safely ashore on the other side, as it were.

Although the Norwegian and Spanish corpora were quite similar in their overall results, they generally differed considerably on slightly lower analytical levels, for example regarding distribution of translations vs. non-translations across tabloids and broadsheets as well as across topic areas. Differing institutional conventions and editorial policies might be the reason; this, too, will have to be studied further.

As regards the microlevel analysis which looked into translation procedures, it was found that both corpora displayed less literal translation and calque, and more domestication and interpretation. This is in line with previous research which has shown that domestication is the main strategy used in news translation. Again, however, there were differences on the lower analytical levels, especially with regard to the numbers of domestication vs. interpretation, where the Norwegian corpus displayed significantly more use of interpretation, while the Spanish corpus more use of domestication. This could potentially be due to some sort of “proficiency assumption”: a Norwegian journalator, who can assume a high degree of ability to read and understand the ESMQ without translation can allow him or herself to stray further from the original source. A Spanish journalator, on the other hand, possibly uncertain about his or her own English proficiency, might find him or herself obliged to provide a close rendering for a reader who needs the help. In order to get closer to a definitive answer, however, we need, again, to actually ask the journalators themselves.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Universo Trump. Consulted on 5 October, 2023, <https://elpais.com/noticias/agr-universo-trump/>.

-

[2]

Lane, James (2021): The 10 most spoken languages in the world. Babel Magazine. Consulted on 6 November, 2021, <https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/the-10-most-spoken-languages-in-the-world>.

-

[3]

Others have drawn attention to the practice of reporters driving “traffic to their legacy platform” (Canter 2015: 888) by linking to their own newsroom content (Artwick 2013. 212) as a way to market their stories (Broersma and Graham 2012: 403).

-

[4]

We follow Paulussen and Harder (2014. 547) in classifying soft news as stories from and on media and show business, popular culture, arts, sports and human interest stories. We acknowledge that the hard/soft news dichotomy somewhat underplays the complexity of the issue, especially in light of the doubtless existence of crossovers between soft and hard news (for example, when showbusiness personalities comment on political issues). The classification that we chose (social/celebrity, sports, and politics) did however allow us to identify types of news cases with a reasonable amount of certainty regarding which category they belong to and, therefore, we have not deemed the issue of such crossovers relevant in this particular study.

-

[5]

Education First (2019): EF English proficiency index (EF EPI). Education first. Consulted on 10 October, 2021, <https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/>.

-

[6]

Eurostat (2021): Foreign language learning statistics. Eurostat: Statistics Explained. Consulted on 10 October 2021, <https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Foreign_language_learning_statistics>.

-

[7]

INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadístic (2021): Encuesta de Características Esenciales de la Población y Viviendas (ECEPOV). Consulted on 6 October, 2023, < https://www.ine.es/prensa/ecepov_2021.pdf>.

-

[8]

Dagbladet [The Daily Magazine]. <https://www.dagbladet.no>.

-

[9]

Verdens Gang (VG) [Way of the World]. <https://www.vg.no>.

-

[10]

One of the newspapers in Spanish in this study, the broadsheet El País has two Latin American versions—El País América and El País México—as well as El País Brasil, and El País Catalán and El País English, but this study is circumscribed to its first iteration: El País España [The Country Spain]. <https://www.elpais.com/espana>.

-

[11]

Although tabloids and broadsheets are still distinguishable in terms of the frequency of certain topics they tend to favour and the ways in which they write about these topics, some have argued that the differences have become more blurred in the last 25-30 years (Pugh 2011. Alba-Juez 2017). While the distinction is relatively clear in the case of the Norwegian newspapers, it is perhaps somewhat more blurred in the case of the Spanish ones.

-

[12]

El Confidencial [The Confidential]. <https://www.https://www.elconfidencial.com/>.

-

[13]

Pugh, Andrew (2011): Study: ‘Tabloid-broadsheet divide has blurred.’ PressGazette: The Future of Media. Consulted on 5 November, 2021, <https://www.pressgazette.co.uk/study-tabloid-broadsheet-divide-has-blurred/>.

-

[14]

Elements in coupled pairs are placed in bold.

-

[15]

Johansen, Martine (2020): Blokkerte mora etter Instagram-blemme. [Blocked her mother after Instagram blunder] Consulted on 10 October, 2021, <https://www.dagbladet.no/kjendis/blokkerte-mora-etter-instagram-blemme/72979465>.

-

[16]

Nissen, Sofie Grønntun (2021): Et lovforslag i Frankrike vekker sinne verden rundt: - Ikke rør hijaben min! [A proposal for a new law in France arouses anger around the world: - Don’t mess with my hijab!] Consulted on 10 October, 2021, <https://www.aftenposten.no/verden/i/lERgGk/et-lovforslag-i-frankrike-vekker-sinne-verden-rundt-ikke-roer-hijabe>.

-

[17]

Matre, Jostein (2021): Darnella (18) blir hyllet som helt etter Floyd-dommen. [Darnella (18) is celebrated as a hero after the Floyd verdict] Consulted on 10 October, 2021, <https://www.vg.no/nyheter/utenriks/i/R97lWJ/darnella-18-blir-hyllet-som-helt-etter-floyd-dommen>.

-

[18]

Schwencke, Morten (2019): Elsket av Justin Bieber og hatet av Taylor Swift. Scooter Braun er musikkbransjens kanskje mektigste bakmann. [Loved by Justin Bieber and hated by Taylor Swift. Scooter Braun is perhaps the most powerful mastermind in the music business] Consulted on 10 October, 2021, <https://www.aftenposten.no/kultur/i/XgEwrn/elsket-av-justin-bieber-og-hatet-av-taylor-swift-scooter-braun-er-mus>.

-

[19]

Ec/Agencias (2021): El «angustioso» vídeo de Roman Protasevich, el periodista detenido en Bielorrusia. Consulted on 5 November, 2021, <https://www.elconfidencial.com/mundo/europa/2021-05-25/video-roman-protasevich-periodista-bielorrusia_3098307/>.

-

[20]

S Moda (2021): La rebelión contra la «cínica dieta» de Will Smith y el lucrativo negocio del ‘antes y después’ de los famosos. Consulted on 5 November, 2021, <https://smoda.elpais.com/celebrities/dieta-will-smith-criticas/?a>.

-

[21]

Ec/Agencias (2021): El «angustioso» vídeo de Roman Protasevich, el periodista detenido en Bielorrusia. Consulted on 5 November, 2021. <https://www.elconfidencial.com/mundo/europa/2021-05-25/video-roman-protasevich-periodista-bielorrusia_3098307/>.

-

[22]

Agencias (2021): La activista de Black Lives Matter Sasha Johnson, grave tras recibir un disparo en Londres. Consulted on 5 November, 2021, <https://elpais.com/internacional/2021-05-24/la-destacada-activista-de-black-lives-matter-sasha-johnson-grave-tras-recibir-un-disparo-en-londres.html>.

-

[23]

See, for example, this video made by the Spanish Real Academia de la Lengua [Royal Academy of Language] created to combat the use of unnecessary Anglicisms in Spanish. Consulted on 10 October, 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBEomboXmTw&t=157s>.

Bibliography

- Alba-Juez, Laura (2017): Evaluation in the headlines of tabloids and broadsheets: a comparative study. In: Ruth Breeze and Inés Olza, eds. Evaluation in Media Discourse. Bern: Peter Lang, 81-119.

- Al-Naimat, Ghazi K. and Saidat, Ahmad M. (2019): Aesthetic symbolic and communicative functions of English signs in urban spaces of Jordan: typography, multimodality, and ideological values. Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics. 10(2):3-24.

- Armentia Vizuete, José Ignacio (1992): El diseño de la prensa española. Revista TELOS. 31(5):7-12.

- Artwick, Claudette G. (2013): Reporters on Twitter: product or service? Digital Journalism. 1(2):212-228.

- Barnard, Steven R. (2016): “Tweet or be sacked”: Twitter and the new elements of journalistic practice. Journalism. 17(2):190-207.

- Bell, Alan (1991): The Language of News Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bergh, Gunnar and Ohlander, Sölve (2020): From national to global obsession: football and football English in the superdiverse 21st century. Nordic Journal of English Studies. 19(5):359-383.

- Bielsa, Esperança and Bassnett, Susan (2009): Translation in Global News. New York: Routledge.

- Bokor, Michael J. K. (2018). English dominance on the internet. In: John I. Liontas, ed. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 1-6.

- Broersma, Marcel and Graham, Todd (2012): Social media as beat: Tweets as a news source during the 2010 British and Dutch elections. Journalism Practice. 6(3):403-419.

- Broersma, Marcel and Graham, Todd (2013): Twitter as a news source: how Dutch and British newspapers used tweets in their news coverage, 2007-2011. Journalism Practice. 7(4):446-464.

- Canter, Lily (2015): Personalised tweeting: the emerging practices of journalists on Twitter. Digital Journalism. 3(6):888-907.

- Canter, Lily and Brookes, David (2016): Twitter as a flexible tool. Digital Journalism. 4(7):875-885.

- Cappon, Rene J. (1991): Associated Press Guide to News Writing. New York: Macmillan.

- Chan, Tak Wing and Goldthorpe, John H. (2007): Social status and newspaper readership. American Journal of Sociology. 112(4):1095-1134.

- Chen, Ya-Mei (2009): Quotation as a key to the investigation of ideological manipulation in news trans-editing in the Taiwanese press. TTR. 22(2):203-238.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1993): From ‘is’ to ‘ought’: laws, norms and strategies in Translation Studies. Target. 5(1):1-20.

- Filmer, Denise (2014): Journalators? An ethnographic study of British journalists who translate. Cultus. 7:135-157.

- Gulyas, Agnes (2017): Hybridity and social media adoption by journalists. Digital Journalism. 5(7):884-902.

- Haapanen, Lauri and Perrin, Daniel (2019): Translingual quoting in journalism: behind the scenes of Swiss television newsrooms. In: Lucile Davier and Kyle Conway, eds. Journalism and Translation in the Era of Convergence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 15-42.

- Haberland, Hartmut (2005): Domains and domain loss. In: Bent Preisler, Anne Fabricius, Hartmut Haberland, et al., eds. The Consequences of Mobility. Roskilde: Roskilde University, 227-237.

- Hannerz, Ulf (1996): Transnational Connections. London: Routledge.

- Hedman, Ulrika and Dierf-Pierre, Monika (2013): The social journalist: embracing the social media life or creating a new digital divide? Digital Journalism. 1(3):368-385.

- Hernández Guerrero, María José (2020): The translation of tweets in Spanish digital newspapers. Perspectives. 28(3):376-392.

- Holland, Robert (2013): News translation. In: Carmen Millan-Várela and Francesca Bartrina, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies. London: Routledge, 332-346.

- Hurtado Santón, María Teresa, González López, Manuel and Encinas Berga, Irene (1992): Anglicismos en la prensa española. Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete. 7:67-82.

- Jakobsen, Ingrid K. (2019): Inspired by image: a multimodal analysis of 10th grade English school-leaving written examinations set in Norway (2014-2018). Acta didactica Norge [Acta didactica Norway]. 13(1):1-27.

- Kuo, Sai-Hua and Nakamura, Mari (2005): Translation or transformation? A case study of language and ideology in the Taiwanese press. Discourse & Society. 16(3):393-417.

- Ljosland, Ragnhild (2014): Language planning confronted by everyday communication in the international university: the Norwegian case. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 35(4):392-405.

- Matsushita, Kayo (2020): Reporting quotable yet untranslatable speech: observations of shifting practices by Japanese newspapers from Obama to Trump. AILA Review. 33(1):157-175.

- Moon, Soo Jung and Hadley, Patrick (2014): Routinizing a new technology in the newsroom: Twitter as a news source in mainstream media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 58(2):289-305.

- Paulussen, Steve and Harder, Raymond A. (2014): Social media references in newspapers: Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as sources in newspaper journalism. Journalism Practice. 8(5):542-551.

- Perrin, Daniel and Ehrensberger-Dow, Maureen (2012): Translating the news: a globally relevant field for Applied Linguistics research. In: Christina Gitsaki and Dick Baldauf, eds. Future Directions in Applied Linguistics. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 352-372.

- Płónska, Dagmara (2014): Strategies of translation. Psychology of Language and Communication. 18(1):67-74.

- Saldanha, Gabriela and O’Brien, Sharon (2013): Research Methodologies in Translation Studies. Manchester: Routledge.

- Sanden, Guro R. (2020): Language policy and corporate law: a case study from Norway. Nordic Journal of Linguistics. 43(1):59-91.

- Santana, Arthur D. and Hopp, Toby (2016): Tapping into a new stream of (personal) data: assessing journalists’ different use of social media. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 93(2):383-408.

- Stetting, Karen (1989): Transediting—a new term for coping with the grey area between editing and translating. In: Graham Caie, Kirsten Haastrup, Arnt Lykke Jakobsen, et al., eds. Proceedings from the Fourth Nordic Conference for English Studies. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 371-382.

- Sunde, Anne Mette and Kristoffersen, Martin (2018): Effects of English L2 on Norwegian L1. Nordic Journal of Linguistics. 41(3):275-307.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2015): Fifteen years of journalistic translation research and more. Perspectives. 23(4):634-662.

- van Doorslaer, Luc (2012): Translating, narrating and constructing images in journalism with a test case on representation in Flemish TV news. Meta. 57(4):1046-1059.

- Vinay, Jean-Paul and Darbelnet, Jean (1958/1995): Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A Methodology for Translation. (Translated from French by Juan C. Sager and Marie-Josée Hamel) Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Von Nordheim, Gerret, Boczek, Karin and Koppers, Lars (2018): Sourcing the sources: an analysis of the use of Twitter and Facebook as a journalistic source over 10 years in The New York Times, The Guardian, and Süddeutsche Zeitung. Digital Journalism. 6(7):807-828.

- Wallsten, Kevin (2015): Non-elite Twitter sources rarely cited in coverage. Newspaper Research Journal. 36(1):24-41.

- Willnat, Lars and Weaver, David H. (2018): Social media and U.S. journalists: uses and perceived effects on perceived norms and values. Digital Journalism. 6(7):889-909.

- Zagood, Mohammed Juma (2019): An analytical study of the strategies used in translating Trump’s tweets into Arabic. Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies. 3(1):22-34.

List of tables

Table 1

Macrolevel analysis of the Norwegian corpus

Table 2

Macrolevel analysis of the Spanish corpus

Table 3

Translation procedures in the Norwegian corpus

Table 4