Abstracts

Abstract

Non-profit corporations benefit from significant tax subsidies, but they are largely regulated by corporate statutes rather than tax law. Recent legislative reforms in Canada have sought to modernize non-profit statutes to reflect the changing non-profit sector, with a focus on increasing accountability and fairness. Yet, despite the increasingly national reach of non-profits, governance and financial transparency requirements can differ considerably between jurisdictions. This article compares non-profit rules about directors and financial review in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, and federally. It demonstrates how modern non-profit law reforms make regulatory choices about governance and financial transparency requirements based on local policy priorities. The article then uses tax expenditure analysis to argue for a national perspective that considers the different regulatory burdens facing non-profits receiving the same federal tax subsidies. It finds that inconsistent rules between jurisdictions raise significant accountability and fairness concerns. For smaller non-profits, uninformed incorporation choices may result in a higher compliance burden. For non-profits seeking a lighter regulatory load, the uneven regulatory landscape may lead to jurisdiction shopping. The article argues that the increased harmonization of non-profit law across Canada is key to continuing the work of modernizing non-profit law. It concludes by identifying potential law reforms and their limitations.

Résumé

Les sociétés à but non lucratif bénéficient d’importantes subventions fiscales, mais elles sont largement réglementées par la législation portant sur les sociétés plutôt que par le droit fiscal. De récentes réformes législatives au Canada ont cherché à moderniser les lois encadrant les organisations à but non lucratif afin de refléter l’évolution de ce secteur, en mettant l’accent sur la responsabilité et l’équité. Pourtant, malgré la portée de plus en plus nationale des organisations à but non lucratif, les exigences en matière de gouvernance et de transparence financière peuvent différer considérablement d’une juridiction à l’autre. Cet article compare les règles encadrant la direction et l’examen financier des organisations à but non lucratif en Alberta, en Colombie-Britannique, en Ontario et au niveau fédéral. Il démontre comment les réformes modernes du droit des organisations à but non lucratif reflètent des choix réglementaires, en matière de gouvernance et de transparence financière, qui varient en fonction des priorités politiques locales. L’article se base ensuite sur une analyse des dépenses fiscales pour plaider en faveur d’une perspective nationale qui prendrait en compte les fardeaux réglementaires différents auxquels sont confrontées les organisations à but non lucratif bénéficiant des mêmes subventions fiscales fédérales. Il constate que les règles incohérentes entre les juridictions soulèvent d’importantes préoccupations quant à la responsabilité et à l’équité. Pour les petites organisations à but non lucratif, des choix d’incorporation mal informés peuvent entraîner un fardeau de conformité plus lourd. Pour les organisations à but non lucratif qui recherchent une charge réglementaire plus légère, le paysage réglementaire inégal peut les conduire à faire un choix de juridiction (« jurisdiction shopping »). L’article soutient que l’harmonisation accrue du droit des organisations à but non lucratif au Canada est essentielle à la poursuite du travail de modernisation de ce domaine de droit. Il conclut en identifiant les réformes juridiques potentielles et leurs limites.

Article body

Introduction

This article critically evaluates the non-profit legal landscape in Canada after law reforms to modernize non-profit legislation by the federal government in 2011,[1] by British Columbia in 2016,[2] and by Ontario in 2021.[3] It analyzes director qualifications and financial transparency requirements for non-profits under tax law, the federal non-profit statute, and non-profit statutes in Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario.[4] Using tax expenditure analysis, the article argues for a national perspective on non-profit regulation that considers the different regulatory burdens facing non-profits across Canada.

Non-profits across Canada benefit from generous federal tax subsidies but face different regulatory burdens depending on the jurisdiction in which they incorporate.[5] The non-profit income tax exemption cost the federal government approximately $95 million in foregone tax revenue in 2019,[6] and its provincial counterpart in Ontario cost the province $50 million.[7] The non-profit income tax exemption is a tax expenditure. Tax expenditures are spending programs delivered through the tax system. For tax scholars and policymakers, tax expenditures provide subsidies through foregone tax revenue and should be evaluated as government spending programs.[8] Key tax policy considerations include whether the subsidy is distributed fairly, the reasonableness of the compliance and administrative burden, and whether the government spending program and its recipients are sufficiently accountable for the funds received.[9]

This article applies tax expenditure analysis to assess the regulation of non-profits receiving non-profit tax expenditures. The uneven rules across jurisdictions raise significant accountability and fairness concerns. For smaller non-profits, uninformed incorporation choices may result in a higher compliance burden. For non-profits seeking a lighter regulatory load, the unequal regulatory landscape may lead to jurisdiction shopping. The article argues that modernizing non-profit law requires increased harmonization of governance and financial requirements. It concludes by identifying law reform options and their limitations.

Why should people living in Canada be concerned about jurisdictional variations in non-profit regulation? Non-profits receive significant public funding through the non-profit income tax exemption and related tax expenditures. Canada has over 170,000 non-profits, and approximately 86,000 of those groups are also registered as charities.[10] The non-profit and charity sector accounted for 8.5% of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2017.[11] Non-profits include large health and education institutions, sports clubs, and community organizations supporting women, new immigrants, people living in poverty, Indigenous people, racialized people, and 2SLGBTQI+ people. Not all non-profit corporations have only altruistic purposes or limited resources. Chambers of commerce, industry lobbying groups, and trade associations are often non-profits, and the top sources of revenue for non-profits reporting income to the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) are sales revenue, membership fees, and government funding.[12]

Most people interact with non-profit organizations regularly, whether as employees, members, service users, donors, or volunteers. The Canadian public has a direct stake in a non-profit regulatory regime that is fair, meets the sector’s needs, provides financial transparency, and protects the public. Yet many people are unaware that the regulation of a Canadian non-profit differs depending on its incorporating statute and other legislation in the jurisdiction where the non-profit operates. Within Canada, a non-profit can incorporate federally or under a local provincial or territorial statute.[13] Significant differences exist between statutes, and for non-profits that also obtain charitable status through the Canada Revenue Agency, charity law adds a layer of complexity. For example, audit requirements under non-profit statutes differ significantly. A non-profit incorporated under the federal non-profit statute may face audit obligations not required under provincial laws in British Columbia or Alberta.[14]

By focusing on the regulation of non-profits under corporate statutes and on non-profit tax expenditures, this article contributes to Canadian legal scholarship on non-profit and charity law. Most existing literature concerns charitable tax expenditures and the regulation of charities;[15] there has been much less attention paid to the regulatory framework for non-profits and non-profit tax subsidies.[16] Following over a decade of non-profit law reform in Canada and increased attention to the non-profit income tax exemption by the Canada Revenue Agency,[17] the article provides a timely addition to the discourse.

The article begins, in Part 2, by providing an overview of the regulatory context for non-profits and registered charities in Canada, including differences between non-profit status and charitable status under the Income Tax Act. Part 3 presents the corporate statutory context for non-profits in Canada, both historically and today, and recent law reforms seeking to modernize non-profit statutes. Part 4 situates federal non-profit tax subsidies as tax expenditures and argues that the non-profit statutes that largely regulate Canadian non-profits should be evaluated from a national perspective to account for federal tax subsidies. In Part 5, the article presents a comparative analysis of directors’ qualifications and financial review rules under the federal non-profit statute,[18] the provincial non-profit statutes in Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario, and charity law.[19] Part 6 argues for the increased harmonization of non-profit law across Canada and identifies potential law reforms.

I. Non-Profit Organization vs. Charitable Status

For the general public, the difference between incorporating as a non-profit corporation and obtaining charitable status is often unclear. A non-profit is not necessarily a registered charity. Incorporating as a non-profit creates a distinct legal entity with a board of directors and voting members. Registering for charitable status is a separate process administered by the Canada Revenue Agency. Both qualifying non-profits and registered charities are exempt from paying income tax,[20] but only non-profits with charitable status can provide tax receipts for donations.

The regulation of charities has been the subject of much public attention and law reform advocacy.[21] The regulation of non-profits under the Income Tax Act is minimal in comparison and has attracted significantly less attention.[22] This section provides an overview of how non-profits and charities are established and their treatment under tax law.

A. Non-Profit Corporations

Under the Canadian Constitution, the federal and provincial governments share jurisdiction over corporate law.[23] When incorporating a non-profit, incorporators have statutory choices to make. They may incorporate under federal non-profit legislation or provincial/territorial statutes. Approximately twenty percent of non-profits are incorporated federally, and the rest are incorporated under provincial/territorial statutes.[24] Non-profits incorporated under Canadian statutes can operate in any province or territory if they meet local registration requirements.

The decision on where to incorporate is guided by an organization’s needs and differences between statutory regimes. Incorporation choices are also influenced by access to justice issues, with self-represented organizations navigating legal choices based on the publicly available legal information. For example, accessible and bilingual information about the federal incorporation process and the rules for federal non-profits are available online on Corporations Canada,[25] but similar legal information about provincial non-profit law may be more difficult to access in some jurisdictions.

An organization incorporated under a non-profit statute does not automatically qualify for the non-profit income tax exemption under paragraph 149(1)(l) of the Income Tax Act. Generally, a non-profit self-assesses as eligible, and there is limited scrutiny unless the Canada Revenue Agency selects the organization for further review.

A non-profit qualifies as a “non-profit organization” (NPO) under paragraph 149(1)(l) of the Income Tax Act if it meets three criteria.[26] First, the NPO must not fall under the legal definition of a charity.[27] An NPO is “a club, society or association … organized and operated exclusively for social welfare, civic improvement, pleasure or recreation or for any other purpose except profit.”[28] Second, the NPO must be organized and operated exclusively for non-profit purposes.[29] NPOs can earn revenue, but profits must be incidental, and the revenue must be earned while carrying out the organization’s non-profit purposes.[30] Third, any income from the non-profit cannot be paid or benefit “any proprietor, member, or shareholder” of the entity.[31]

The Canada Revenue Agency provides that an NPO must file an annual return if:

-

it received or was entitled to receive taxable dividends, interest, rentals, or royalties totalling more than $10,000 in the fiscal period;

-

the total assets of the organization were more than $200,000 at the end of the immediately preceding fiscal period (the amount of the organization’s total assets is the book value of these assets calculated using generally accepted accounting principles);

-

it had to file an NPO (a non-profit organization) information return for a previous fiscal period.[32]

The Canada Revenue Agency estimates that there are 100,000 non-charitable non-profits in Canada. Only twenty percent of NPOs file annual returns.[33]

B. Charitable Status

Provinces have the jurisdiction under the Canadian Constitution to regulate charities and related bodies that are “in and for the province.”[34] Despite these provincial powers, the Canada Revenue Agency is the main regulator of registered charities. Some provinces have also enacted supplemental legislation relating to charitable property and fundraising.[35]

To obtain charitable status under the Income Tax Act, a non-profit must undergo a separate process administered by the Canada Revenue Agency.[36] Eligibility is based on the entity having purposes that are of public benefit and that fall under the four “heads” of charity: relief of poverty, advancement of education, advancement of religion, and other purposes of benefit to the community the courts have found to be charitable.[37] The four categories of charitable purposes have evolved over time, incrementally expanding under the common law as the courts and the tax authorities recognized the charitable nature of numerous purposes.[38]

Registered charities are exempt from income tax and can issue charitable tax receipts for donations, which incentivize donations by reducing the amount of tax that the donor pays.[39] Charities can also receive donations from other organizations with charitable status, including the charitable foundations that help fund the charity sector, such as the United Way. They also obtain tax subsidies through the Goods and Services Tax/Harmonized Sales Tax (GST/HST), provincial taxes, and municipal tax expenditures.

C. Tax Regulation

Registered charities face many legal obligations under the Income Tax Act and from their regulator, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Amongst other rules, an organization must use its resources for its charitable purposes, only engage in allowable activities, and maintain adequate direction and control over its resources to ensure that they are properly used for charitable purposes.[40] Charities are also obligated to respect a disbursement quota, which dictates minimum yearly spending requirements.[41] The ratio of a charity’s fundraising costs to funds raised must be reasonable.[42] Numerous other policies are published by the CRA to advise charities on their legal obligations.[43]

Non-profits without charitable status are subject to comparatively little regulation by the tax authorities. The main source of the CRA’s regulation of non-profits is the rare review of whether a non-profit is an eligible NPO under the Income Tax Act and the requirement that NPOs file annual returns. Due to the lack of regulation by the tax authorities, there is little data about non-profits in Canada, but existing information highlights the need for more transparency. A study of NPO annual returns in Canada found that revenue was “far higher than expected”[44] and concluded that “we know very little” from the data on NPO returns because of the limited number of non-profits required to file returns and the lack of information provided.[45]

A multi-year review of non-profits completed in 2014 by the CRA provides further insight.[46] During the project, the tax authority randomly selected and reviewed 4.5 percent of non-profits claiming the non-profit income tax exemption.[47] The CRA reported that “between 40.7 [percent] and 46.3 [percent]” of the non-profits that it studied did not comply with one or more of the requirements for the exemption.[48] It broke down the non-compliance further, reporting that “between 29.3 [percent] and 34.5 [percent]” of the organizations studied had high-risk non-compliance that “would result in increased tax liability to the organization.”[49] The remaining non-compliance was assessed as “low risk” that “could be corrected through increased education.”[50] Overall, the most common high risk non-compliance issues relate to:

-

profits that were not incidental or income that was not related to its non-profit objectives;

-

organizations that had unreasonable reserves, surpluses or retained earnings; or

-

income payable or made available for the personal benefit of any proprietor, member or shareholder.[51]

The CRA’s review indicates that the rates of non-compliance by non-profits under Canadian tax law are significant. Yet, most regulation of non-profits in Canada is not by the tax authorities but rather by an organization’s governing corporate statute. The following section presents the non-profit statutory landscape in Canada, beginning with the historical context.

II. Corporate Statutes for Non-Profits

Historically, many non-profits in Canada had to incorporate under legislative schemes designed for business corporations, with only a small section of corporate statutes carved out for non-profit corporations.[52] General provisions had to be adapted to fit the non-profit context. Understanding and applying these legislative schemes to non-profit corporations made for a muddled regulatory context, with hybrid rules that were challenging to decipher and use.

Before non-profit law reform, Ontario’s “existing legislation was over 50 years old; at the federal level, it was close to 100 years old.”[53] Similiarly, Alberta’s Societies Act was almost 100 years old.[54]

Prior to the most recent wave of legislative reforms, Saskatchewan modernized its non-profit legislation in 1995.[55] The Saskatchewan legislation is noteworthy for its division of non-profits into two categories – membership corporations, and charitable corporations – with the latter facing more regulatory obligations.[56] Karen J. Cooper and Jane Burke-Robertson described the Saskatchewan legislation as “the most modern and comprehensive non-profit legislation currently in force in Canada” before the more recent law reforms federally and in British Columbia and Ontario.[57]

In response to long-standing calls for non-profit statutory reform, the Canadian non-profit legislative context has changed significantly since 2010.[58] The federal Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act came into force in October 2011.[59] The new federal non-profit sought to increase governance and transparency requirements, “to curb abuses by self-serving Directors, by strengthening member powers to approve significant changes to the corporate form, and by adding record-keeping and filing requirements to facilitate oversight.”[60] The federal government described the legislation as “clearer, modern and flexible, and much better suited to the needs of today’s not-for-profit corporations.”[61]

Ontario introduced the Not-for-Profit Corporations Act in 2010, a year after the federal non-profit statute, although it did not come into force until October 2021.[62] The Ontario government similarly asserts that the Ontario statute “modernizes the way not-for-profit corporations operate,” “clarifies rules for governing,” and “increases accountability.”[63]

The focus on accountability and governance in modernizing non-profit law reflected public preoccupations about the regulation of the non-profit sector. In 2012, Rayna Shienfield wrote in the non-profit sector publication, the Philanthropist,

One only needs to look as far as their local newspaper to observe the increasingly vocal call for the accountability of nonprofit organizations. Whether the issue at hand is administration costs or the need for transparency, stakeholders, including the general public, are taking more interest in organizations that receive “public funds” (whether they be donor dollars, tax benefits, or government grants).[64]

Linda J Godel, writing about the new federal and Ontario non-profit statutes in the Philanthropist that same year, stated that the “clear message from the CNCA and the ONCA is transparency and accountability.”[65] She noted that one of the most significant changes for both statutes is the introduction of a new classification system for non-profits. Both new statutes assign different governance and financial review requirements if a non-profit receives a specific threshold of funds from members of the public or government funding. Note that the new statutes do not include the non-profit income tax exemption or other non-profit tax subsidies in the statutory definition of public funding.

British Columbia also modernized its provincial non-profit law with the new Societies Act, which came into force in 2016.[66] The provincial government highlighting that the legislation “allow[s] for more flexibility in how societies operate, while still protecting the public interest.”[67] Similarly to the new federal and Ontario legislation, the new B.C. statute distinguishes between member-funded organizations and those receiving public funds. Again, there is no reference to income tax subsidies in the legislative definition of public funds. Notably, the new B.C. non-profit statute went in a different direction from the federal and Ontario legislation. Only approximately 1% of non-profits — referred to as “reporting societies” — must undertake audits.[68]

Other jurisdictions have been less successful in modernizing non-profit laws. For example, in Quebec, a major corporate reform took place in 2011, when the new Business Corporations Act came into force.[69] A separate non-profit legislative regime was planned in Quebec alongside the business law reform, and detailed consultations occurred but have yet come to fruition.[70] Quebec non-profits are still constituted under Part III of the Companies Act, and reference must continue to be made to other parts of the Companies Act to ascertain the rules applicable to operating a non-profit.

In Alberta, non-profits can incorporate under the Companies Act or the Societies Act, with quite different rules applying.[71] In 1982, this “legislative mish-mash” led Baz Edmeades to call for a single modern non-profit statute in the province.[72] Over thirty years later, calls for non-profit law reform in Alberta continue. In 2015, the Alberta Law Reform Institute advocated for a new, modernized non-profit statute, but to date the province has only enacted limited non-profit law reform.[73]

Alberta and Saskatchewan both recently amended their legislation governing non-profits to remove residency requirements for directors.[74] Alberta amended the Companies Act in 2020 to decrease the compliance burden for non-profits. It sought “to reduce outdated requirements and make it easier for non-profits to register and operate,” to harmonize “the province with other provinces,” and to provide organizations with “the flexibility to appoint the best-suited candidates, regardless of where they live.”[75] Similarly, in 2021 Saskatchewan described its amendments to their non-profit legislation to remove residency requirements for directors as modernizing law reforms that “reflect current practices, replace outdated rules and language, reduce red tape, and create efficiencies for organizations by emphasizing the use of modern technologies.”[76]

At the local level, each jurisdiction’s non-profit law reforms reflect government policy priorities, often reached in consultation with the non-profit sector. At a national level, however, the lack of regulation of non-profits by the CRA combined with non-profit statutory differences result in uneven accountability mechanisms and compliance burdens at the national level.

The next section introduces the tax expenditure concept and argues for the need to analyze non-profit regulation from a national perspective, with reference to tax policy criteria.

III. Tax Expenditure Analytical Framework

Charities and non-profits are both subsidized through the tax system. These tax subsidies are tax expenditures because but for the preferential tax treatment they provide, the state would earn tax revenue. Stanley Surrey introduced the concept of tax expenditures to describe government programs that reduce tax payable, whether through income deductions, tax credits, or tax exemptions.[77] The Canadian government defines tax expenditures as measures that “are used to achieve a policy objective that deviates from the core function of the tax system, at the cost of lower tax revenues.”[78]

Registered charities receive robust tax expenditures. For example, when individuals donate to registered charities, they receive a tax credit that lowers the amount of tax they pay. This tax credit results in a loss of tax revenue because the individual is effectively transferring the tax amount that they would otherwise pay to the government to a registered charity of their choice.

The total cost of the charitable tax credit to the federal treasury was $3.2 billion in 2019.[79] The federal government estimated that its corporate sibling, the corporate charitable tax deduction, cost $655 million.[80] The Ontario government estimated its provincial equivalents that year to cost $750 million for the charitable donation tax credit and $130 million for the corporate charitable tax deduction.[81] Comparatively, the estimated cost of the federal income tax exemption for non-profits was significantly lower, at $95 million in 2019.[82] At the provincial and territorial level, Ontario reported that the non-taxation of the income of non-profits cost the province $50 million in foregone tax revenue in 2019.[83]

Registered charities and qualifying non-profits also receive GST/HST subsidies. To qualify, at least 40% of a non-charitable non-profit’s revenue must be from government funding.[84] The estimated cost of the federal GST/HST rebate in 2019 was $315 million for registered charities and $75 million for qualifying non-profits.[85] Ontario estimated its provincial portion of the HST rebate for charities at $405 million, and for qualifying non-profits at $60 million in 2019.[86] Non-profit organizations and charities may also be eligible for property tax exemptions and rebates. Eligibility criteria vary from province to province, and some municipalities offer an additional property tax rebate.[87]

Tax expenditure reporting shows non-profits receiving large tax subsidies, although significantly less than registered charities. These non-profit tax subsidies are widely understood to be tax expenditures or spending programs through the tax system that support non-profits through tax exemptions. There has been some limited resistance to this characterization. For example, Boris Bittker argued that non-profit organizations do not earn income, so tax revenue is not foregone.[88] Bittker’s theory has been countered by arguments that it has limited application because he was only referring to organizations that earn revenue through donations.[89] Lori McMillan’s study of annual returns filed by non-profits in Canada found that non-profits do earn income, with the largest sources of income from sales, membership fees, and government funding.[90]

Since non-profit tax expenditures are essentially government spending programs providing grants through the tax system via foregone revenue, they must be regularly evaluated to ensure the programs meet their objectives.[91] Financial reporting on the cost of tax expenditure programs is an internationally recognized best practice recommended by the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.[92] Like many countries,[93] Canada releases a yearly federal tax expenditure report, providing estimates and projections of the annual cost of each program and a brief description of the expenditure and its objectives.[94] The annual report lists the non-profit income exemption alongside other tax subsidies for non-profits and charities.[95]

For tax policy scholars, financial reporting is crucial to government accountability for tax expenditures, but it is only the first step. Tax expenditures should be evaluated just like other government spending programs, including assessing the fairness of distribution of the subsidy, the regulatory burden imposed, and the accountability mechanisms to ensure that public funds are used to carry out the tax expenditure’s objectives.[96] From an equity perspective, for example, tax policy scholars must consider the fairness of the distribution of a tax subsidy. Tax expenditure analysis considers the compliance burden imposed on the targeted recipients of tax subsidies, and the administrative burden imposed on regulators.[97] Accountability through financial and governance oversight rules helps ensure the appropriate use of public funds. Expenditure analysis should also consider equality issues and the potential impact of discrimination, when assessing “who benefits from the expenditure and, of course, who does not.”[98]

The Auditor General of Canada describes the key elements for evaluating tax expenditures as “policy need (relevance), efficiency, effectiveness, equity,” “spending alternatives,” and “foregone revenue.”[99] Similar criteria are recognized by the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.[100] The United States Government Accountability Office analyzes tax expenditure programs by considering their efficiency, equity, simplicity, transparency, and administrability.[101] Tax expenditure evaluation also recognizes that program design requires trade-offs. Some regulatory choices may increase adherence to one policy priority, such as accountability through financial oversight requirements, but result in a higher compliance burden.

Non-profit law reforms in Canada show jurisdictions balancing policy concerns that reflect tax policy criteria such as fairness, efficiency, administrability, and accountability needs. Jurisdictional variations in non-profit regulation result from regulators having different policy priorities and accepting the resulting trade-offs.

IV. Comparative Analysis of Non-Profit Laws

This section analyzes the regulation of non-profits under federal non-profit legislation and provincial non-profit legislation in Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario, as well as any additional requirements if the non-profit is also a registered charity under the Income Tax Act. It focuses on three rules: residency requirements for directors, requirements for a minimum number of directors, and financial review requirements. For each legal rule, the section also presents the policy reasons provided to explain regulatory choices and discusses the potential consequences of uneven regulation.

A. Number of Directors

A minimum number of directors is a well-recognized tool for increasing the accountability of corporations.[102] More directors, particularly outside directors, increase the ability of boards to play an oversight role.[103] A corporation with only one director is more vulnerable to mismanagement.

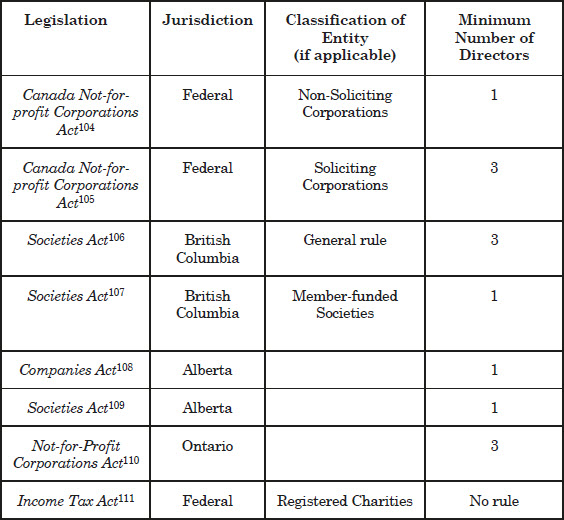

Table 1 below summarizes the rules about the minimum number of directors for non-profits.

Table 1

Minimum Number of Directors[104][105][106][107][108][108][109][110][111]

For Ontario, the need for oversight and accountability led to the requirement of a minimum of three directors for all non-profits incorporated under its provincial non-profit legislation.[112] The province also added an additional requirement for “public benefit corporations.”[113] Public benefit corporations include all registered charities as well as non-charitable non-profits receiving more than $10,000 a year in public funding and donations. Only one-third of the directors of a public benefit corporation can be employees of the non-profit. This additional rule increases outside oversight for organizations benefiting from donations or government funding. Note, however, that even non-profits that do not qualify as public benefit corporations under Ontario’s legislation are likely self-assessing as a non-profit organization under the Income Tax Act and, if they earn income, benefiting from tax subsidies.

At the federal level, the Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act shows similar attention to “transparency and accountability.”[114] The new federal non-profit act establishes different rules for organizations that receive government funding and donations. Soliciting corporations are federal non-profits that receive over $10,000 a year in public funding or donations from non-related parties.[115] This definition does not include public tax subsidies.

Soliciting corporations under the federal act require a minimum of three directors and at least two of those directors must not be employees or officers of the non-profit or its affiliates.[116] Unlike the Ontario provincial non-profit statute, which always requires three directors, the federal non-profit made a different regulatory choice: federal non-soliciting corporations may have only one director, lowering their compliance burden.[117]

British Columbia’s new Societies Act allows for member-funded societies with only one director, but all other societies need at least three directors.[118] Many non-profits do not qualify as member-funded societies under the B.C. legislation, including registered charities, student societies, hospitals, and groups receiving $20,000 or 10% of the society’s gross income in public funding and donations, whichever is greater (with no reference to tax subsidies). The B.C. Minister of Finance’s discussion paper on the reform of the Societies Act explains this regulatory choice:

The Society Act currently requires that all societies have at least three directors. This requirement is intended to help ensure joint decision-making and accountability, and is generally not hard for most societies to fulfill. However, the need for multiple directors can create administrative difficulties in some situations and may lead to the appointment of “straw” directors, put on the board simply to fulfill the requirement.

The three-director minimum would no longer apply to private societies, but would be retained for public ones. The requirement would add an extra assurance of collective oversight and accountability appropriate for publicly-funded societies, and is consistent with requirements for other entities that engage the public trust, including community service cooperatives, financial institutions and publicly-traded companies.[119]

In modernizing its non-profit law, B.C. decided to lower the number of directors for member-funded non-profits, decreasing their administrative obligations, while retaining the need for three directors for publicly funded societies to ensure more oversight and accountability.

Alberta’s Societies Act has no reference to a minimum number of directors and the minimum number is presumably one.[120] There was a minimum number of directors for non-profit organizations incorporated under Alberta’s Companies Act, unless modified at a general meeting, but it was removed.[121] Note that non-profits that incorporate under the province’s Societies Act are not allowed to engage in significant business activities, while non-profits incorporated under the Companies Act are allowed to, provided those funds are used to promote the organization’s purposes.[122]

For non-profits also registered as charities, the Income Tax Act does not require a minimum number of directors.

The requirements for a minimum number of directors under these non-profit statutes and charity law show regulators making different choices with similar policy goals in mind: fairness, accountability, efficient regulation, and a reasonable compliance burden. In Ontario, for example, three directors are a necessity regardless of the nature of the non-profit, creating more oversight but also more compliance obligations. For the federal government, it is sufficient to only require soliciting corporations to have a minimum number of directors.

These disparate rules result in non-profits across the country being subject to different governance standards. For example, a registered charity incorporated federally may have just one director if it is a non-soliciting corporation, while a non-profit incorporated provincially in Ontario requires at least three directors regardless of whether it is classified as a public benefit corporation. A non-profit organization incorporated under Alberta’s statutes could have just one director.[123] The result is a wide variance in minimum governance rules and compliance costs for non-profits receiving the same federal tax subsidies.

B. Residency Requirements

Non-profit corporate statutes differ on whether any directors of a non-profit corporation must be a resident of the incorporating jurisdiction. From a tax policy perspective, residency requirements for directors—whether Canadian or provincial—increase a non-profit’s connection to a jurisdiction. For non-profits benefiting from tax subsidies, residency requirements help ensure that tax subsidy recipients are within the Canadian tax nexus. The removal of residency requirements, however, provides for more flexibility in the digital age where non-profit activities are less localized. It also facilitates international organizations headquartering in Canada.[124]

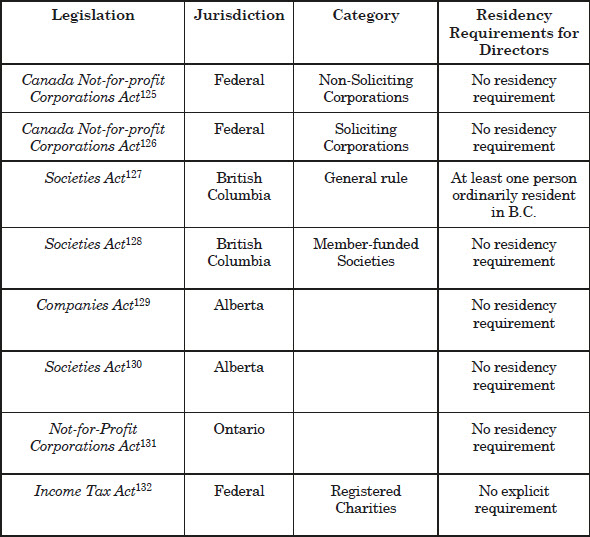

Table 2 below summarizes residency requirements for directors:

Table 2

Residency Requirements for Directors[125][126][127][128][129][130][131][132]

The federal non-profit statute has no Canadian residency requirement for directors.[133] In Ontario, there is no requirement for directors to be residents of the province under the Not-for-Profit Corporations Act.[134]

In British Columbia, for public corporations incorporated under the Societies Act, at least one of the obligatory three directors must ordinarily reside in the province.[135] Private companies incorporated under the same legislation can have only one director that has no residential connection to the province. Alberta’s Companies Act used to require that a minimum of 50% of directors be ordinarily resident of Alberta,[136] but the province eliminated this requirement when the 2020 Red Tape Reduction Implementation Act came into force.[137] There are no provincial residency requirements for directors under Alberta’s Societies Act.[138]

For non-profits with charitable status, the Income Tax Act requires registered charities to be resident in Canada.[139] If a registered charity is a non-profit incorporated in Canada, the Income Tax Act deems it to be a resident of Canada.[140] In practice, a charity must demonstrate adequate direction and control over its resources, and if the charity has foreign activities, the residency of its directors in Canada may be a key factor in determining the charity’s residency status.[141]

The residency rules for directors of non-profits reflect different regulatory priorities. For British Columbia, it was important to maintain a requirement that some directors of publicly funded non-profits have a connection to the province, but it chose to remove that requirement for member-funded organizations. The government discussion paper stated:

There are situations where a single extra-provincial director could be desirable for a private society, and the restriction would therefore be removed for those societies.

The one-BC director requirement would be retained, however, for public societies where the handling of public money increases the benefits of having a local presence on the board. Requiring that one (out of three or more) directors of a public society live in the province is not onerous in our view, and in fact reflects the reality of most BC societies.[142]

The B.C. discussion paper reflects the province’s balancing act between ensuring directors maintain a connection to the province for accountability reasons and ensuring a reasonable regulatory burden.

In Alberta, the government went in a different direction by removing director residency requirements for non-profits under Alberta’s Companies Act. The government explained the policy rationale for these changes:

Changes were made to the Companies Act to reduce outdated requirements and make it easier for non-profits to register and operate. The Alberta residency requirements for non-profit boards of directors was eliminated. This aligns the province with other provinces and gives non-profits the flexibility to appoint the best-suited candidates, regardless of where they live.[143]

The province’s framing of the removal of director residency requirements as a red tape reduction strategy situates residency requirements as an “outdated” and unjustified compliance burden. Not all Albertans agreed with this legal change. Richard Feehan, the NDP MLA for Edmonton-Rutherford, spoke against the removal of similar residency requirements for directors of business corporations, stating:

The directors of the companies don’t need to be Albertans at all. I don’t understand how that helps Albertans. It certainly helps American corporations. It certainly helps corporations from across Canada, but it does not appear to be directed toward protecting the ability of Albertans to make decisions about Albertan questions and problems, does it?[144]

Canada, Alberta, and Ontario all made similar regulatory decisions not to require Canadian or provincial residency for directors. It appears that a lack of director residency requirements is useful for international groups looking to set up in Canada. Mark Blumberg, a Canadian charity lawyer, writes that international organizations are increasingly looking to Canada as a place to set up their headquarters:

Some fear the rising tensions and uncertainty in the US and how this could affect the operation of their organizations. For others they would prefer to have offices or headquarters in Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver rather than in the US or a number of other countries which are increasingly unstable, xenophobic or repressive.[145]

Canada may have good public policy reasons for supporting non-profits with international activities wishing to headquarter in Canada: for example, to support international aid and human rights efforts in another country. From a Canadian tax policy perspective, however, a registered charity may be a more appropriate regulatory framework. Non-charitable non-profits benefit from tax subsidies but are subject to much less regulation. Registered charities are subject to a more robust regulatory framework and must demonstrate that their mission falls within a charitable purpose recognized under Canadian law. Charities must maintain direction and control over their operations, and Canadian resident directors could be advanced as a means to do so.[146] Similar rules for non-profits would increase Canadian accountability for the international operations of non-charitable non-profits. However, since non-profits benefit from fewer tax subsidies than registered charities, the lack of residential requirements may be an acceptable trade-off if there are other accountability mechanisms, such as financial transparency requirements.

C. Financial Review Requirements

When choosing statutory financial review requirements, regulators must weigh the benefits of financial transparency against the costs of increased compliance obligations. Current financial review requirements for non-profits in Canada run on a spectrum between a simple requirement to provide a financial report to members and the rigorous requirement of an audit by an independent professional accountant. As the level of financial review increases, so does the cost.

Corporations Canada provides helpful definitions of financial review options. A financial compilation imposes a lower burden. It requires financial statements in a form that follows Canadian accounting rules, but does not require a professional accountant and offers no assurances about the accuracy of the information.[147] A “review” is more stringent; it is undertaken by an independent public accountant, following accounting principles, but only addresses the plausibility of the financial statements.[148] The most rigorous requirement is an “audit”, which requires an independent public accountant to provide an opinion on whether “the financial statements present a fair picture of the organization’s financial position.”[149]

Even if there are no legal financial review requirements, other factors may impose that requirement. An organization’s bylaws may self-impose financial verification and reporting. Funders may also require a review or audit for grants or for annual funding amounts above a certain level.[150]

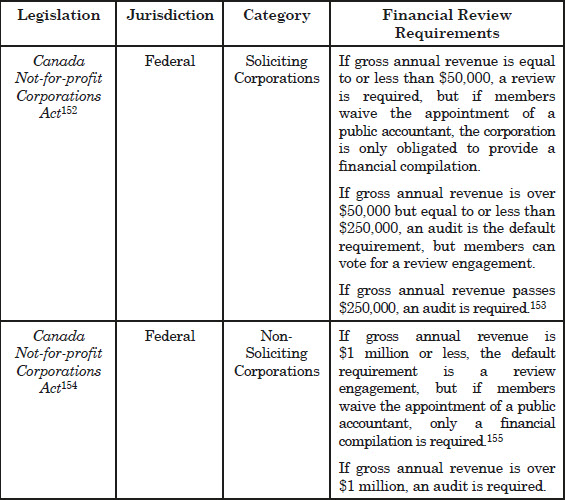

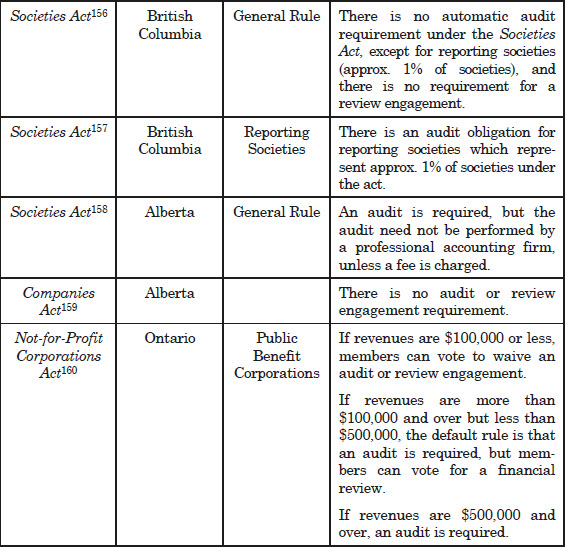

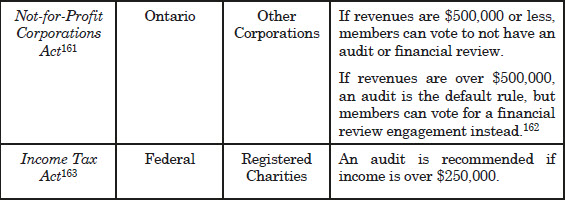

Table 3 summarizes the differences in financial review requirements for non-profits and registered charities under federal, B.C., Alberta, and Ontario legislation, and under charity law.

Table 3

Minimum Financial Review Requirements[151][152][153][154][155][156][157][158][159][160][161][162][163]

Under the federal Not-for-profit Act, soliciting corporations that receive more than $10,000 per year in public funding have financial review or audit requirements.[164] Soliciting corporations with $50,000 or less in gross annual revenue can opt for a simpler and less rigorous financial compilation. Once an organization’s gross annual revenue is more than $50,000, an audit is the default requirement, although members may opt for a financial review until gross annual revenue passes $250,000, at which point the organization must have an audit.[165] For non-soliciting federal corporations with $1 million or less in gross annual revenue, the default requirement is a review engagement, but there is an opt-out mechanism that allows for only a financial compilation.[166] Non-soliciting corporations with over $1 million in gross annual revenue must have an audit.[167]

Ontario’s Not-for-Profit Act also requires more stringent financial review requirements for public benefit corporations, but with a different classification system than the federal legislation. For public benefit corporations with $100,000 or less in revenues, members can vote to waive both an audit and financial review.[168] Once an organization’s revenues are above $100,000 but below $500,000, an audit is needed unless members vote for a financial review instead.[169] When revenues rise to $500,000 and above, an audit is necessary.[170] For Ontario non-profit corporations that are not public benefit corporations, when revenues are $500,000 or less, members can vote not to have an audit or financial review.[171] If revenues are over $500,000, an audit is required but members can vote for a financial review.[172]

In British Columbia, there is no audit requirement for almost all societies governed by the province’s Societies Act.[173] The exception is an audit requirement for reporting societies, which represent 1% of organizations governed by the Societies Act.[174] British Columbia does, however, require the reporting of remuneration paid to directors, employees, and contractors.[175] Alberta’s Societies Act requires an audit, but the audit need not be performed by a professional accounting firm unless required by the non-profit’s bylaws, or if a fee is being paid for the audit.[176]

For registered charities, there is no audit requirement under the Income Tax Act, but CRA recommends annual audited financial statements for charities with a gross annual revenue exceeding $250,000.[177] Charities must, however, disclose financial information in the yearly T3010 Registered Charity Information Return, including revenue, expenses, and director and employee compensation.

Note that where financial review requirements are imposed, non-profit statutes also have voting rules for waiving those requirements which are not detailed in this paper. These rules also serve to add transparency and accountability. For example, for a federally incorporated soliciting corporation with revenues over $50,000 and up to $250,000, a special resolution is required to waive the audit requirement and substitute it with a financial review engagement.[178] Similarly, for an Ontario public benefit corporation with revenues over $100,000 but less than $500,000, an extraordinary resolution is required to change the default audit requirement to a financial review engagement.[179] The same statutes also detail requirements for appointing a public accountant and waiving the requirements for that appointment.[180] The federal act further requires soliciting corporations to file financial statements with Corporations Canada.[181]

Different regulatory choices about financial review requirements for non-profits focus on balancing accountability with the need for a reasonable compliance burden, albeit with different results. The new federal and Ontario non-profit legislation aim to address the need for financial transparency while accommodating smaller non-profits. A 2002 federal non-profit law reform discussion paper notes that audits provide “the maximum degree of transparency and accountability,” but “smaller organizations would be disproportionately affected by the expense of annual audits.”[182] A 2008 Ontario consultation paper similarly addresses the policy balancing act between increased accountability and a fair compliance burden for smaller organizations, noting that “the cost and administrative burden associated with undergoing an annual audit can be considerable, especially for small not-for-profits.”[183]

Smaller non-profits with fewer resources have limited access to professional legal and accounting advice. In the legal realm, the lack of access to counsel is well-recognized. Public legal information websites attempt to help fill these gaps.[184] Michael Blatchford and others note that many professional advisors are not aware of the legal and accounting needs of the non-profit sector.[185] The Ontario and federal non-profit statutes address concerns about compliance burdens and the costs of financial review for small non-profits with a classification system that distinguishes between publicly funded and privately funded organizations. These statutes provide a sliding scale of financial review obligations depending on the non-profit’s size and category.

British Columbia and Alberta took a different approach, deferring to members and others, such as funders, to dictate financial transparency requirements. British Columbia’s Minister of Finance emphasized that non-profits have limited access to legal advice and are often volunteer-run.[186] It noted that “earlier consultations were firmly against any notion of broadening the current Act’s audit requirements”[187] and “[c]omplex legal rules and requirements should be avoided if possible.”[188]

Alberta’s Societies Act “leaves many of the key governance issues to be determined by the by-laws of an individual organization.”[189] The Alberta Law Reform Institute writes that while financial review requirements contribute to “the development of an accountable non-profit sector,” a modernized non-profit statute in Alberta should continue to allow organizations to determine their own financial review obligations.[190] In a nod to increasing accountability, however, the Alberta Law Reform Institute recommends that non-profit statutes contain default financial review requirements as a fallback when non-profits’ bylaws do not contain such rules.

Financial review requirements show each jurisdiction balancing its policy priorities differently, but from a national perspective, the result is a complex and uneven legal landscape, with financial accountability requirements that range from minimal oversight mechanisms to rigorous requirements. A federally incorporated non-profit without charitable status can have more rigorous financial transparency requirements than a registered charity incorporated provincially under the Societies Act in Alberta or British Columbia. If a non-profit is incorporated federally, its financial verification requirements depend on the amount of revenue gathered from public sources, ranging from a simple financial compilation to a full audit.[191] If the organization is incorporated under Alberta’s Societies Act, an audit is required, but that audit does not need to be conducted by a professional accounting firm, so long as no fee is charged.[192] Almost all societies incorporated in British Columbia face no statutory financial review requirements. Small non-profits may make uninformed incorporation choices and opt into a more costly oversight regime, and better-informed non-profits may choose a jurisdiction with less (or no) financial review requirements. The public, who rely on non-profits for many goods and services, and who are potential donors, are unlikely to know that the financial oversight rules binding a non-profit operating in its jurisdiction may differ significantly depending on its governing statute.

This section focused on comparing three key rules about non-profit governance and financial requirements, but these are just a small selection of the jurisdictional variations in non-profit law across Canada that raise policy concerns at the national level. For example, individuals recently convicted of fraud are ineligible to serve as directors of non-profits in British Columbia, or as directors of a registered charity, but may still qualify as a director in another Canadian jurisdiction.[193] To provide another example, only three provinces in Canada have a statutory framework to regulate fundraising: Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Prince Edward Island. However, if the non-profit is also a registered charity, it will be subject to further fundraising rules set out by the CRA.[194] In the digital age—where online fundraising campaigns reach across jurisdictional borders—the lack of consistent fundraising rules may inadequately protect a non-profit’s donors, participants, and members, and fail to provide sufficient accountability for organizations receiving public subsidies.

V. Harmonizing Canadian Non-Profit Law

Federal and provincial/territorial variations in non-profit regulation reflect each government’s policy priorities. In choosing the level of governance and financial review requirements, regulators weigh concerns including fairness, accountability, and the need for a reasonable regulatory burden, mirroring the policy criteria used to evaluate tax expenditures. From a national perspective, however, jurisdictional differences create an inconsistent and at times inequitable regulatory regime for non-profits.

Fairness and accountability issues arise when non-profits without access to informed legal counsel may incur a higher compliance burden due to their incorporation choices, and more resourced non-profits can opt into a lighter regulatory regime. In the American context, Peter Molk found that most non-profits incorporate where their headquarters are located, but those that incorporate out of jurisdiction do so in jurisdictions with lighter regulation.[195] Molk identified “a potential ‘stroll’ to the bottom” for non-profits seeking ‘weaker oversight.’[196] In the Canadian context, there are similar concerns that jurisdictional variations in non-profit regulation allow some non-profits to choose jurisdictions with lower regulatory oversight requirements.

Protecting the public is also a key task of non-profit regulators. Canadian non-profits and charities play an essential role in providing public goods and services.[197] The sector is increasingly the main source of health, cultural, and social services. Non-profits and charities work on the frontlines with some of Canada’s most marginalized populations. Susan Phillips writes that for registered charities, “[t]ransparency, as one component of accountability, has long been an important principle in the charitable sector and is a requirement of most charity regulators.”[198]

For non-charitable non-profits in Canada, however, transparency is lacking. The 2019 report of the Special Committee on the Charitable Sector highlights concerns about the lack of accountability mechanisms for non-profits:

Several witnesses discussed the lack of information and transparency regarding NPOs. For example, the committee heard that the ITA imposes only “minimal” reporting requirements on NPOs and requires “no transparency for what is reported.”

The absence of oversight was also raised by Mr. Blumberg, who reminded the committee that, despite the lack of transparency surrounding their activities, NPOs still receive significant tax benefits.”[199]

To continue the work of modernizing non-profit law in Canada, the regulatory framework requires increased standardization of governance and financial transparency rules across Canada. Minimum non-profit governance and financial transparency requirements would create a floor for oversight and accountability rules for non-profits that benefit from tax subsidies. Standardizing key aspects of non-profit law would help prevent non-profit jurisdiction shopping and reduce complexity for less-resourced non-profits. National minimum standards would also increase the protection of the many members of the Canadian public who interact with non-profits.

Lawyers, scholars, and advocates have long called for the modernization of charity and non-profit law in Canada.[200] Decades of charity law reform advocacy and scholarship include proposals for legislative and regulatory changes. For example, the Uniform Law Conference of Canada (ULCC) introduced the Uniform Charitable Fundraising Act in 2005,[201] but to date, it has not been adopted by any provinces.[202] In 2009, Adam Aptowitzer advocated for a new Federated Canadian Charities Council that heightens the provinces’ regulatory role for charities.[203] In 2011, David Duff called for federal and provincial governments to consider joint regulatory initiatives that extend beyond registered charities to the larger non-profit sector.[204]

In 2018, Susan Phillips, in testifying before the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, asked: “[w]hat is a “modern” regulator in this sector? ... Is the Charities Directorate of the Canada Revenue Agency suited to be a modern regulator?”[205] She went on to state that, “[t]he pros and cons of various models have been debated for years, but I still think we need to revisit them”[206] As Canada grapples with the question of what a modern charity law regime should look like, the ongoing work of modernizing non-profit law must not be left behind. Modernizing corporate legislation to provide non-profits with their own statutory homes was an essential step, but the larger project of modernizing non-profit law in Canada requires increased federal/provincial harmonization and cooperation.

Regulators and researchers should respond to ongoing calls for inter-jurisdictional regulation by evaluating the feasibility of a joint provincial and federal initiative to share the oversight of the non-profit and charitable sector.[207] The Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector (ACCS), founded by the federal government in 2019, could be a key actor in this work, in cooperation with the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Network of Charity Regulators, which was founded in 2004 in response to prior consultations with the charity and non-profit sector.[208]

Sustained regulatory cooperation between federal and provincial/territorial jurisdictions may seem unachievable at this time. Securities regulation in Canada, however, long the subject of jurisdictional contention, provides a potential model. Despite ongoing jurisdictional struggles, securities law necessitates some daily inter-jurisdictional cooperation to protect the public interest and promote economic development.[209] In the non-profit context, there are similar needs to protect the public and support a significant economic sector. National and multi-jurisdictional securities instruments provide an example of daily regulatory cooperation.

Most likely, any standardization of non-profit law in the near future would be through the federal government’s taxing authority. Currently, access to the non-profit income exemption is largely self-assessed by non-profits. The CRA is already the primary regulator of registered charities, through the federal government’s taxing authority, and it has recently increased its attention to the non-profit tax exemption.[210]

From a tax policy perspective, the CRA may be the most appropriate regulator of accountability requirements to access federal non-profit tax expenditures. Additional regulation by the tax authorities would supplement regulation under non-profit corporate statutes. For example, the Income Tax Act could increase financial reporting requirements for non-profits with a certain threshold of public revenue. McMillan recommends that the Income Tax Act require all non-profits in Canada to file an annual return, rather than the approximately 20% that currently must file.[211] Annual information tax returns would also assist governments in more accurately reporting the costs of non-profit tax expenditures based on the amount of tax revenue foregone. The 2019 report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector recommends that the ACCS review the treatment of non-profits under the Income Tax Act, including public disclosure requirements, standardizing financial reporting, and assessing whether to distinguish between public benefit non-profits and membership non-profits.[212] It alsorecommended that the ACCS consider whether non-profit information returns should be publicly available to increase transparency.[213]

In contemplating regulatory changes, governments must also be cautious not to place too large of a regulatory burden on smaller non-profits. During Canadian non-profit law reform discussions at the federal and provincial levels, concerns about overburdening small non-profits were repeatedly raised, particularly the cost of financial review requirements that would “disproportionately affect” smaller organizations,[214] as well as limited access to legal and accounting advice.[215] Nicole Dandridge warns of the undue burden that increased regulation by the federal tax authorities may place on small profits in the United States.[216]

Still, we must be cautious not to assume that all small non-profits are operated for the public benefit. McMillan cautions that while the exemption for non-profits may have been aimed at “small-scale grassroots types of organizations that bettered society,” in the current Canadian content, “there is no societal benefit that must be felt in order for the organization to be granted nonprofit status”. She argues that non-profit organizations operated for private benefit should not be eligible for the non-profit tax exemption.[217]

Reporting from the federal non-profit regulator show that its classification system intended to exclude small non-profits from a heavier regulatory burden may be over-inclusive. Despite the intention of the federal non-profit legislation to increase accountability and transparency, the majority of federal non-profits are classified as non-soliciting corporations and subject to less transparency and governance obligations.[218] Regulators need to find the balance between the need for a reasonable compliance burden for small non-profits with the need for accountability from non-profits benefiting from public funding, including tax subsidies.

Conclusion

The Canadian public depends on the non-profit and charity sector for many public goods and services. In recognition of their essential role, non-profits across Canada benefit from tax and other public funding. At the same time, not all non-profits provide public benefits,[219] and transparency in exchange for non-profit tax subsidies is lacking.[220] By charting the modernizing non-profit legal landscape in Canada, this article helps lay the groundwork for future non-profit law reforms that include a tax policy perspective.

Law reforms sought to modernize non-profit legislation federally and in British Columbia and Ontario. From a national perspective, however, the non-profit legal framework in Canada is too decentralized and uneven for a modern non-profit sector. Non-profits operate in multiple jurisdictions, and in the digital era, activities increasingly reach across provincial/territorial borders. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the digital transformation of the non-profit sector.[221] Online fundraisers reach potential donors across Canada and beyond.

To continue the work of modernizing non-profit law in Canada, it is time for a more coherent regulatory framework. Differences in non-profit rules about governance and financial transparency raise accountability and fairness concerns. Going forward in the project of modernizing non-profit law in Canada, regulators must consider both a national and a local perspective on non-profit regulation. Both viewpoints are needed to balance the key policy concerns of fairness, accountability, and a reasonable compliance burden, while accounting for the heterogeneity of the non-profit sector.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

See Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act, SC 2009, c 23 [CNCA].

-

[2]

See Societies Act, SBC 2015, c 18 [BC Societies Act]. See also Societies Regulation, BC Reg 216/2015, s 12-13.

-

[3]

See Not-for-Profit Corporations Act, 2010, SO 2010, c 15 (This Act came into force eleven years after it was introduced, on October 19, 2021) [Ontario NPCA].

-

[4]

See CNCA, supra note 1; Societies Act, RSA 2000 c S-14, ss 25–27 [AB Societies Act]; Companies Act, RSA 2000 c C-21, ss 89, 131–134 [AB Companies Act]; BC Societies Act, supra note 2, ss 35–39, 43–45; Ontario NPCA, supra note 3, s 23, 68–84; Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp) [Income Tax Act].

-

[5]

Non-profit corporations are referred to as “non-profits” throughout this paper. Non-profit corporations can apply to register as charities, but they can also be non-charitable non-profits.

-

[6]

See Canada, Department of Finance, Report on Federal Tax Expenditures: Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations 2020, Catalogue No F1-47E-PDF (Ottawa: Department of Finance, 2020) at 205 [Federal Tax Expenditures 2020]. One expects that these amounts are underestimated, due to the difficulties in estimating revenue amounts not taxed and/or reported by non-profit organizations.

-

[7]

See Ontario, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Transparency Report, 2019” (last modified 06 November 2019), online: Queen’s Printer for Ontario <budget.ontario.ca/2019/ fallstatement/transparency.html> [perma.cc/8VXB-LSQY] [Taxation Transparency Report].

-

[8]

See generally Stanley S Surrey, Pathways to Tax Reform: The Concept of Tax Expenditures (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973); Government of Canada, “Part 1 - Tax Expenditures and the Benchmark Tax System: Concepts and Estimation Methodologies” (last modified 15 February 2023), online: Government of Canada <www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/services/publications/federal-tax-expenditures/2023/part-1.html> [perma.cc/6XRT-U7FG]; OECD. “Tax Expenditures in OECD Countries” (05 January 2010), online OECD Library <www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/tax-expenditures-in-oecd-countries_9789264076907-en> [perma.cc/M2JT-SFCZ].

-

[9]

See Neil Brooks, “Policy Forum: The Case Against Boutique Tax Credits and Similar Tax Expenditures” (2016) 64:1 Can Tax J 65 at 96.

-

[10]

See Imagine Canada, “Canada’s Charities & Nonprofits” (2021), online (pdf): Imagine Canada <imaginecanada.ca/sites/default/files/Infographic-sector-stat-2021.pdf> [perma.cc/F2LZ-AQU5]. See also Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “2021 NFP Act Statutory Review Consultation Paper” (last modified 18 June 2021), online: Government of Canada <www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cilp-pdci.nsf/eng/cl00910.html> [perma.cc/4CTR-JRGK].

-

[11]

See Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, supra note 10.

-

[12]

See Lori A McMillan, “Noncharitable Nonprofit Organizations in Canada: An Empirical Examination” in Kim Brooks, ed, The Quest for Tax Reform Continues: The Royal Commission on Taxation Fifty Years Later (Toronto: Carswell, 2013) 311 at 321.

-

[13]

A non-profit may need to meet certain registration requirements if operating in a province or territory but not incorporated under a statute in that jurisdiction. See Donald J Bourgeois, The Law of Charitable and Not-for-Profit Organizations, 5th ed (Toronto: LexisNexis Canada, 2016) at 109–111.

-

[14]

See CNCA, supra note 1, s 2(5.1); Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Regulations, SOR/2011–223, s 16 [NFP Regulations]; BC Societies Act, supra note 2, s 111(1); AB Societies Act, supra note 4, s 26(2)(d) (this section of the AB Societies Act requires that societies provide “the audited financial statement presented at the last annual general meeting of the society” (AB Societies Act, supra note 4, s 26(2)(d)) to the Registrar, but these financial statements do not need to be provided by a professional accounting firm).

-

[15]

See e.g. Neil Brooks, “The Tax Credit for Charitable Contributions: Giving Credit where None Is Due” in Jim Phillips, Bruce Chapman & David Stevens, eds, Between State and Market: Essays on Charities Law and Policy in Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001) 457; Kathryn Chan, “Taxing Charities/Imposer les Organismes de Bienfaisance: Harmonization and Dissonance in Canadian Charity Law” (2007) 55:3 Can Tax J 481; Kathryn Chan, “The Function (or Malfunction) of Equity in the Charity Law of Canada’s Federal Courts” (2016) 2:1 Can J Comparative & Contemporary L 33; David G Duff, “Tax Treatment of Charitable Contributions in Canada: Theory, Practice, and Reform” (2004) 42:1 Osgoode Hall LJ 47; David G Duff, “Charities and Terrorist Financing” (2011) 61:1 UTLJ 73 [Duff, “Charities and Terrorism”]; Tamara Larre, “Allowing Charities to ‘Do More Good’ through Carrying on Unrelated Businesses” (2016) 7:1 ANSERJ Can J Nonprofit & Soc Economy Research 29; Adam Parachin, “Funding Charities Through Tax Law: When Should a Donation Qualify for Donation Incentives?” (2012) 3:1 ANSERJ Can J Nonprofit & Soc Economy Research 57 [Parachin, “Funding Charities Through Tax Law]; Adam Parachin, “Policy Forum: How and Why to Legislate the Charity-Politics Distinction Under the Income Tax Act” (2017) 65:2 Can Tax J 391 [Adam Parachin, “Policy Forum]; Susan D Phillips, “Shining Light on Charities or Looking in the Wrong Place? Regulation-by-Transparency in Canada” (2013) 24:3 Voluntas: Intl J Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations 881 [Phillips, “Regulation-by-Transparency in Canada”]; Samuel Singer, “Charity Law Reform in Canada: Moving from Patchwork to Substantive Reform” (2020) 57:3 Alta L Rev 683.

-

[16]

See Lori A McMillan, “Noncharitable Nonprofit Organizations and Tax Policy: Working Toward a Public Benefit Theory” (2020) 59:2 Washburn LJ 301 [McMillan, “Noncharitable Nonprofit Organizations”]; Lori McMillan, “The Concept of Income as Related to the Non-charitable Nonprofit Subsector in Canada” (2010) 16:3 L & Bus Rev Americas 457 [McMillan, “Concept of Income”]; Robert B Hayhoe & Nicole K D’Aoust, “Policy Forum: Using Dual Structures for Political Activities Charities and Non-Profits in the Same Family of Organizations” (2017) 65:2 Can Tax J 357; Baz Edmeades, “Reformulating a Strategy for the Reform of Non-Profit Corporation Law – An Alberta Perspective” (1984) 22:3 Alta L Rev 417.

-

[17]

See e.g. Canada Revenue Agency, “Non-Profit Organization Risk Identification Project Report” (last modified 17 February 2014); Michael Blatchford, Bryan Millman & Esther Oh, “Non-Profit Organizations and Registered Charities – What Should Keep Them (And You) Awake at Night?” (Paper delivered at the 2016 British Columbia Tax Conference), (2016) 12:1 Canadian Tax Foundation 1.

-

[18]

See CNCA, supra note 1, ss 126, 172.

-

[19]

See AB Societies Act, supra note 4, ss 25–27; AB Companies Act, supra note 4, ss 89, 131–134; BC Societies Act, supra note 2, ss 35–39, 43–45; Ontario NPCA, supra note 4; Income Tax Act, supra note 4.

-

[20]

See Income Tax Act, supra note 4, ss 149(1)(f), 149(1)(l).

-

[21]

For more on charity law reform in Canada from 1978 to 2019, see generally Singer, supra note 15.

-

[22]

See McMillan, “Noncharitable Nonprofit Organizations”, supra note 16; McMillan, “Concept of Income”, supra note 16; Hayhoe & D’Aoust, supra note 16 at 359; Edmeades, supra note 16 at 446–49.

-

[23]

See e.g. Constitution Act, 1867 (UK), 30 & 31 Vict, c 3, ss 91(2), 92(11), reprinted in RSC 1985, Appendix II, No 5 [Constitution Act, 1867].

-

[24]

See Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, supra note 10 at para 7.

-

[25]

See “Not-for-profit corporations” (last modified 19 January 2023), online: Corporations Canada <corporationscanada.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cd-dgc.nsf/eng/h_cs03925.html> [perma.cc/ 9JEQ-8H59].

-

[26]

See Terrance S Carter, Maria Elena Hoffstein & Adam Parachin, Charities Legislation & Commentary (Ontario: LexisNexis Canada, 2019) at 8–9.

-

[27]

See Canada Revenue Agency, “Non-Profit Organization Risk Identification Project Report”, supra note 17.

-

[28]

Income Tax Act, supra note 4, s 149.1(1)(l).

-

[29]

See Canada Revenue Agency, “Non-Profit Organization Risk Identification Project Report”, supra note 17.

-

[30]

See David Stevens & Faye Kravetz, “Current Developments In the Application Of Paragraph 149(1)(l) Of the Income Tax Act” (2013) 25:3 The Philanthropist J 1, online: <thephilanthropist.ca/2013/12/current-developments-in-the-application-of-paragraph-14911-of-the-income-ta-x-act/> [perma.cc/PLL6-7M2R].

-

[31]

Ibid.

-

[32]

“Income Tax Guide to the Non-Profit Organization (NPO) Information Return” (last modified 28 February 2020), online: Canada Revenue Agency <www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/publications/t4117/income-tax-guide-non-profit-organization-information-return.html#C1_NPO_return > [perma.cc/UKE8-83R].

-

[33]

See McMillan, supra note 12 at 315–16 (McMillan notes that this number increased steadily since the requirement to file was introduced in 1993).

-

[34]

Constitution Act, 1867, supra note 23, s 92(7) (references to provincial powers in the Constitution include territorial powers).

-

[35]

See e.g. Charitable Purposes Preservation Act, SBC 2004, c 59 [Charitable Purposes Preservation Act]; Charitable Fund-Raising Act, RSA 2000, c C-9 [Charitable Fund-Raising Act]; Charities Accounting Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.10 [Charities Accounting Act]. See also Bourgeois, supra note 13 at 331–35.

-

[36]

See Income Tax Act, supra note 4, ss 149.1(1), (“registered charity”); “Apply to become a registered charity” (last modified 27 November 2019), online: Canada Revenue Agency <www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/registering-charitable-qualified-donee-status/apply-become-registered-charity.html> [perma.cc/ 7FUZ-T6S5].

-

[37]

See Commissioners for Special Purposes of Income Tax v Pemsel, [1891] AC 531, [1981-4] All ER 28; Vancouver Society of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women v MNR, [1999] 1 SCR 10, 169 DLR (4th) 34.

-

[38]

See e.g. Donald J Bourgeois, The Law of Charitable and Not-for-Profit Organizations, 3rd ed (Markham: Butterworths, 2002) at 33 (for a discussion of the evolution of charity law and eligibility for charitable status in Canada); Mayo Moran, “Rethinking Public Benefit: The Definition of Charity in the Era of the Charter” in Jim Phillips, Bruce Chapman & David Stevens, eds, Between State and Market: Essays on Charities Law and Policy in Canada (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001) 251; Mayo Moran & Jim Phillips, “Charity and the Income Tax Act: The Supreme Court Speaks” in Jim Phillips, Bruce Chapman & David Stevens, eds, Between State and Market: Essays on Charities Law and Policy in Canada (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001) 343.

-

[39]

See Income Tax Act, supra note 4, ss 149(1)(f), 149.1(1), 110.1(1)–(2), 118.1(1)–(3).

-

[40]

See ibid, s 149.1.

-

[41]

See ibid, ss 149.1(1)(“disbursement quota”), 149.1(2)(b), 149.1(3)(b), 149.1(4)(b).

-

[42]

See “Fundraising by registered charities” (last modified 10 May 2019), online: Canada Revenue Agency <www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/policies-guidance/fundraising-registered-charities-guidance.html > [perma.cc/9RC2-MF7A].

-

[43]

See “Index of guidance products and policies” (last modified 30 November 2022), online: Canada Revenue Agency <www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/policies-guidance/alphabetical-index-policies-guidance.html > perma.cc/E6MJ-TPBY].

-

[44]

McMillan, supra note 12 at 327.

-

[45]

Ibid.

-

[46]

See Canada, Canada Revenue Agency, Non-Profit Organization Risk Identification Project Report, (Ottawa: CRA, October 2013) [CRA, NPORIP]; Kate Robertson, “CRA’s ‘Non-Profit Organization Risk Identification Project Report’” (26 March 2014), online (blog): Blumbergs Canadian Charity Law <www.canadiancharitylaw.ca/blog/cras_non_profit_organization_risk_identification_project_report/ > [perma.cc/TJ5Z-JCGR]; Carter, Hoffstein & Parachin; supra note 26, Carter, Hoffstein & Parachin at 8–9.

-

[47]