Abstracts

Abstract

This article illustrates perspectives on Métis cultural identity, belonging, and positionality, within the context of wellness. As authors, we have the privilege of sharing stories from 24 Métis women, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse people—living or accessing services on the unceded territory of the Lək’wəŋən-speaking peoples (in so-called Victoria, British Columbia). Their stories illustrate personal and intergenerational journeys of reclaiming Métis identity, while also highlighting the importance of culture, community, family, land, and location. As Métis researchers conducting Métis-specific research, we also share our own positionalities and reflect on our responsibilities to community and to the original caretakers of the land.

Keywords:

- Métis people,

- urban,

- identity,

- culture,

- wellness,

- community

Article body

Introduction

For Métis people, connection to culture, land, and identity are integral components of health and wellness (Auger, 2016; Monchalin, 2019). Research has shown that Indigenous peoples’ health is promoted and protected through the right to speak Indigenous languages, identify as Indigenous peoples, participate in land-based practices, and practice ceremony and other forms of spirituality (Greenwood & de Leeuw, 2012). In this way, cultural identity—which is associated with pride, connection to community, a sense of belonging, and social purpose—is a critical determinant of Métis peoples’ health (Auger, 2021a).

Métis people are one of three constitutionally recognized groups of Indigenous peoples in Canada. As descendants of early fur trade relationships, Métis people have collectively developed distinct cultures, languages, identities, and ways of life (Chartrand, 2007; Macdougall, 2017). Beyond genetics, culture and kinship ties have shaped and supported Métis families and communities, as “Métis identities are nurtured and sustained by the stories, traditions and cultural practices taught by our grandmothers, grandfathers, and ancestors” (Macdougall, 2017, p. 5). As a result of violent colonial policies and practices, the loss of cultural identity has also been cited as a challenge across Métis communities in Canada (Auger, 2021b; Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, 2013). Colonialism has directly impacted the health of Métis families and communities, shaping the quality of available services as well we the barriers that Métis people often face in trying to access and receive these services (Monchalin, 2019).

With the resurgence of Métis identity, Métis people are re-discovering, reclaiming, and remembering their connection to Métis culture and community. Cultural revitalization has been associated with decreased stigma around being Métis (Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, 2013). Beyond decreasing stigma, however, the resurgence of Métis ways of knowing and being contributes to healthy people, families, and communities (Auger, 2021a). This paper presents narratives on Métis cultural identity and journeys to understanding what it means to be Métis from the voices of urban Métis women, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse people living in Victoria, British Columbia (BC). These stories around Métis identity arose within a larger project that aimed to understand the experiences of Métis women, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse people living in or accessing health and social services in Victoria.

Location

Despite BC being home to over 90,000 self-identified Métis people (Statistics Canada, 2017), it has largely been constructed as a “place where no Métis have lived (or continue to live)” (Legault, 2016, p. 229). Métis scholar Legault (2016) explains that this narrative was shaped from “political, legal, and scholarly discourses centered on the expansion of colonialism through the fur trade, notions of cultural essentialism, and legal forms of recognition” (p. 229). And yet, records show that Métis people have existed in what later became known as BC as early as the late 18th century. Métis history in Victoria, BC included the formation of the Victoria Voltigeurs (1851–1858), a military unit that was formed and led by Governor James Douglas (Barkwell, 2008; Goulet & Goulet, 2008). The Victoria Voltigeurs consisted largely of Métis men alongside French settlers and Iroquois men (Barkwell, 2008; Goulet & Goulet, 2008). The Voltigeurs lived in Colquitz Creek—an area within the Saanich municipality in Greater Victoria—and this land was later “given” to the Métis Victoria Voltigeurs upon their retirement (Barkwell, 2008). Douglas rewarded their service, which often required the Voltigeurs to respond to “any hostile First Nations people” (Barkwell, 2008, p. 1). Additional narratives around Métis history in Victoria, BC tend to focus on land-ownership and contributions to the founding of Victoria (see: John Work and Isabella Ross as two prominent examples).

Today, Métis people, in BC and elsewhere, often live in urban settings (Statistics Canada, 2017). Richardson (2016) notes that many Métis people “live assimilated lives” in urban centres, where they are largely isolated from other Métis people geographically (p. 18). The Urban Aboriginal Peoples Survey (UAPS) also reported that less than one-third of urban-dwelling Métis people have a very close connection to their community of origin (Environics Institute, 2010). As the most urbanized of all Indigenous peoples, Métis people also face challenges in connecting to the land that come with living in cities. For example, Peters (2011) has described cities as “places of cultural loss and associated cultural vitality with reserves and rural Métis and Inuit communities” (p. 79). At the same time, false dichotomies of city/homeland or urban/traditional can contribute to the misconception of Canadian cities as non-Indigenous, land-less spaces rather than as active Indigenous territories where culture, community, language, and land are very much alive (Christie-Peters, 2016). In fact, many Canadian cities originally emerged in places significant to Métis and other Indigenous groups as gathering spots or settlement areas (Newhouse & Peters, 2003). For example, the city of Winnipeg, home to the largest Métis population of any Canadian city, has been a traditional gathering place for thousands of years and exists today because of its importance among many Indigenous Nations as a place to conduct trade and to participate in ceremonies (Burley, 2014; Newhouse & Peters, 2003). Many Urban Métis people across Canada are in fact living within their ancestral homelands. Nevertheless, Urban cities can be a particularly contentious place to assert one’s Indigenous identity (Lawrence, 2004).

In their research on urban Indigenous identities, Lawrence (2004) illustrates the significance of severed community ties for people whose identities are rooted in a connection to land and people. Wilson (2008) further suggests that beyond merely shaping identity, the land is part of Indigenous identity and shapes all aspects of our lives. Richardson (2016) describes displacement from land as an ongoing challenge for Métis people who, after being largely relocated from their traditional homeland, Métis “continue to be wanderers in non-Métis spaces” (p. 65). As a result of this positioning, Métis people often report that they walk “between” or “within” multiple worlds; as Leclair (2002) notes: “My people have lived for at least two hundred years within le pays en haut, that ‘middle ground’ between two worlds, indigenous and settler” (p. 163). The practice of walking in multiple worlds has not always been easy for Métis people and many of the participants described a feeling of isolation from both European and Indigenous communities. These experiences are rooted in Métis histories of racism and dispossession from Indigenous communities, as well as contemporary issues of isolation from both Western and Indigenous communities.

Methods

In this project we used the Conversational Method for conducting relational Métis research in an online setting. As Cree scholar Dr. Margaret Kovach (2010) articulates, the Conversational Method involves a collaborative and flexible approach to sharing knowledge through conversational-style interviews. While conversational interviews are not exclusively used within Indigenous research, they align with Indigenous methodologies and storytelling practice and allow for relational practice and reflexivity, which we used throughout the course of this research.

Self-Locating

Indigenous approaches to research emphasize the importance of sharing our positions as researchers (Absolon & Willett, 2005). Our identities and experiences shape the lenses that we use to conduct research; it is therefore both ethical and practical that we, as Métis women and researchers, each share our self-locations through brief introductions (Gaudet et al., 2020). We recognize that Métis scholars have long asserted the need for Métis women to write and (re)right our narratives, particularly through sharing stories that showcase our strengths (Leclair & Nicholson, 2003).

Monique Auger

I am Métis on my mother’s side and French on my father’s side. My family has been living as uninvited visitors on the unceded lands of the Lək’wəŋən-speaking Peoples for six generations. I am a member of the Métis Nation Greater Victoria, one of the local chartered communities within Métis Nation British Columbia. My ancestors were involved in the Fur Trade, but rather than relocating to the Red River Valley after the merge of the Northwest Company and Hudson’s Bay Company, my ancestor Jean Baptiste Jollibois (Métis of Haudenosaunee and French ancestry), maintained his involvement in the industry working in forts across Western Canada. He married into the Nisga’a Nation in the early 1800s to his wife.[1] Jean Baptiste was recruited to Fort Victoria to be part of the Victoria Voltigeurs—the first police force in what is now called British Columbia, and so he and his family relocated to Lək’wəŋən territory. My great-great-great-great grandfather has his name commemorated in the bricks in Bastion Square in Downtown Victoria; it was that same square that he was very likely involved in carrying out horrible acts of colonial law against the Lək’wəŋən peoples. This is both a literal and symbolic truth of the violent and nuanced history that our family has come to understand as Métis people living on lands that do not belong to us.

Carly Jones

I am a proud Métis and Ukrainian woman originally from Saint Adolphe, Manitoba in

Treaty 1 territory. I descend from my mother, Lynn Drobot, and her mother, Fernande

Delorme. The Delorme family lineage carries a proud tradition of French-Michif community

helpers, leaders, organizers and agitators including fur traders, farmers, entrepreneurs,

artists, poets, lifegivers and politicians. Many of our ancestors were community knowledge

gatherers in their own right and I am proud to pick up this work as a contemporary Métis

researcher. I belong to the first generation in my family to be born outside of our

homelands in Manitoba and have lived the majority of my adult life within the Urban

community of East Vancouver, on the unceded, occupied, traditional territories of the

Xwməθkwəy’əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and ![]() peoples. In recent years, I have been privileged to study Indigenous Social

Work at the University of Victoria on the traditional territory the Songhees, Esquimalt

and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples. As an uninvited guest on Coast Salish territories, I strive to

respect the ways of the original people of these lands and to foster good relationships

with other urban Indigenous kin while maintaining close relationships with my relatives

and homelands in Manitoba.

peoples. In recent years, I have been privileged to study Indigenous Social

Work at the University of Victoria on the traditional territory the Songhees, Esquimalt

and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples. As an uninvited guest on Coast Salish territories, I strive to

respect the ways of the original people of these lands and to foster good relationships

with other urban Indigenous kin while maintaining close relationships with my relatives

and homelands in Manitoba.

Renée Monchalin

I am of both Settler and Indigenous background, and my bloodlines flow from Métis-Anishinaabe, Scottish, and French ancestries. I currently reside as an uninvited visitor on the territory of the W̱SÁNEĆ Peoples, and was born and raised in Fort Erie, Ontario, also known as Attiwonderonk (Neutral) territory. I am a citizen of the Métis Nation of Ontario, coming from the historic Métis community of Sault Ste Marie. My ancestors then moved East to Calumet Island on the Ottawa River. Today, I consider my home to be the Niagara River, also known as the Onguiaahra (loosely translated to “thundering waters” or “the strait”) where I grew up. Remembering how water is our first environment, being in the waters that flow through the Niagara River is where I feel most safe, despite the strong current. My oral teachings speak to how many of my ancestors were traditional navigators of the Great Lakes waterways. This teaching was instilled in me by my father, who has a special connection with the water, and reminds me to always show it respect. Like the Niagara River, my bloodlines flow together from many directions and geographies, yet become interwoven as one, and I have the responsibility to respect all of where I am from.

Willow Paul

I am Métis Cree on my father’s side, Gitxsan on my mother’s side, and a mix of white settler on both sides. My traditional Gitxsan name is Zin Zin, a name passed on to me that once belonged to my mother. My family’s connection to our cultures have been disrupted by colonialism, as there are residential school survivors on both my Gitxsan and Métis sides. Despite these attempts at assimilation, my family has continually been resilient. Although we do not live on any of our traditional territories, we have reclaimed identity and culture in multiple ways. The journey of reconnection, relearning, and unlearning is a process of heart work that I am constantly playing with. I am a grateful uninvited guest on the traditional, unceded territory of the Okanagan Syilx people where I have had the privilege to grow up. I study Indigenous Social Work at the University of Victoria, which is situated on the traditional territory of the Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples.

We share our self-locations in written form in a similar way that we shared aspects of ourselves throughout the conversations that we had throughout the research process: as a team in our collective work with this research, with each of the participants during the conversations that were held, and in our process of sharing this work more broadly with our community. We also recognize that we have used our unique lenses—shaped by all of our relationships—in our process of making meaning of the stories and information that were shared with us. In sharing aspects of self, we hope to provide some insight into the lenses we used for this interpretation.

Participants

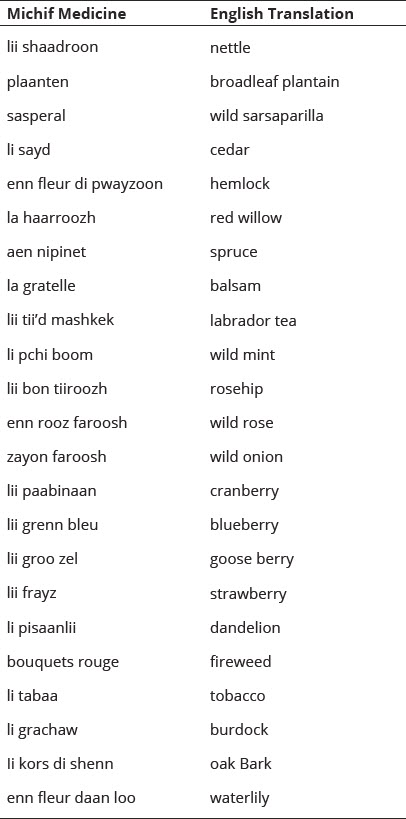

Table 1

Michif medicines used as participant pseudonyms

For this research, we aimed to reach Métis adults who lived in or accessed health and social services in Victoria, BC, and identified as women, Two-Spirit, and/or gender diverse people. We developed a recruitment poster featuring artwork from a local Métis artist, Lynette La Fontaine, which was shared through social media (e.g., Facebook and Instagram), including on the researchers’ accounts and through online community groups. In addition to the visual artwork, the recruitment poster included a description of the research, the study criteria, and contact information. As a result of online engagement, potential participants contacted our research assistant (WP), who had initial conversations with each potential participant to see if they fit the research criteria (related to gender, Métis identity, and location). In cases where participants met the study criteria and maintained interest in participating in the study, an interview over Zoom was scheduled. Within a week of first sharing the poster, we surpassed our recruitment goal, with 24 participants.

Rather than assigning participants a number, we selected Métis plant medicines that can be found on Vancouver Island (Table 1). We wanted to reflect and honour the stories shared with us in this project, as we understand that these stories are medicine (Richardson, 2016). Participants were asked if they were happy to use the Michif medicine name in association with their stories, or if they preferred to use a different name. Table 1 includes the list of Michif plant medicines and their English translations. These names can be found alongside the stories shared in the results of this paper.

Conversational Interviews

Conversational interviews were conducted by two Métis research assistants (CJ, WP). These conversations were hosted online via Zoom or over the phone, given social distancing guidelines during the COVID‑19 pandemic. While online conversations were challenging, through reduced ways of connecting with each participant, the conversations were conducted in a way that honoured our relationships as Métis family and community, as well as the knowledge and stories shared by each participant. Open-ended, flexible interview questions were used, in a way that avoided taking a rigid approach to interviewing. For example, questions related to identity included: (1) How would you describe yourself? And, (2) What does being Métis mean to you? In true conversational fashion, these interviews involved the research assistants sharing aspects of their selves and identities, aligning with our Métis ways of gathering and sharing knowledge through storytelling and kitchen-table conversations (Flaminio et al., 2020). The conversations were around an hour in length, on average.

Each conversation was recorded and transcribed by a third-party professional transcriptionist. To ensure that participants were comfortable with their stories being shared in the research project, each participant was offered the option of having their transcription shared back with them, with an invitation to revise, add, or remove any aspect of the transcript without question. We understand this simple process as a way of operationalizing the Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP™) Principles at a grassroots level, with respect over each person’s ownership of their own story. This process also aligns with a process of “returning to community,” which Anishinaabe scholar Dr. Kathy Absolon (2011) describes in Kaandossiwin: How We Come to Know. Participants were also asked if they were comfortable offering their direct quotes in the analysis; 23 of the 24 participants gave consent to have their direct quotes used, while one preferred to have their stories represented only in summaries.

We sent each participant a thank-you card designed by Métis artist Lynette La Fontaine, as well as a fabric face mask by La Fontaine and Anishinaabe artist Lesley Hampton. Participants were also sent an honorarium of $95 in respect of their time spent interviewing and reviewing their stories.

Thematic Analysis

Analysis refers to the ways that we interpret, or make meaning, of the knowledge shared with us in the research process. Qualitative analytic techniques are used to draw out substantive or conceptual elements and then re-integrate those elements into themes. Métis scholars Cathy Richardson and Jeannine Carriere (2017), among others, assert that thematic analysis can be utilized in Indigenous research as a form of “respectful categorization” that can “contribute to a holistic representation, much like threads woven together… contributing to the integrity of one blanket” (p. 35). They note that this method of meaning making is not exclusively owned by colonial scholars (Richardson & Carriere, 2017).

As a team, we utilized the DEPICT model of analysis, as described by Flicker and Nixon (2014), using NVivo as a tool for assisting our team-based approach to thematic analysis. We developed a codebook based on our initial review of the transcripts, and adapted it collaboratively as needed. Following our group review, we divided the transcripts for a subsequent intensive coding process with two teams. Half of the transcripts were analyzed by WP and checked by MA, and the other half were analyzed by CJ and checked by RM. We met weekly to discuss our interpretations. The thematic analysis, as a whole, was reviewed by the team to ensure there was consensus by way of a shared understanding of across the themes that arose. We recognize that a collaborative approach to analysis—inclusive of participants—would have potentially strengthened our approach to making meaning and interpretation of the knowledge and experiences shared in this research. Due to the sensitive nature of the stories shared, and the concerns around confidentiality expressed by some participants, this approach was not pursued. Instead, sought feedback from participants one-on-one through the optional verification of their transcripts, and through sharing and asking for input on a draft community report.

After finishing our process of thematic analysis, we developed a community report featuring the stories shared by the Métis participants. This report was sent out to project partners and participants for their feedback. Once finalized, the report was sent to Métis communities and local organizations for distribution to service providers and community members. Our approach to disseminating findings from this research was further informed by dialogue with a local Métis Elder, Barb Hulme, and with participants themselves.

Ethics

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Victoria. Aligning with the Chapter 9 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Research Involving First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada, we centred the importance of protecting Métis Knowledge. Additionally, we recognize that the Tri-Council Policy Statement also falls short of fully adhering to Indigenous research ethics, and we sought to operationalize the OCAP™ principles within the context of the grassroots Métis community in Victoria, BC, while prioritizing open and transparent communication throughout the research process. We also sought and received guidance from our Elder, Barb Hulme, from project inception through dissemination.

Results

From a Métis perspective, culture and identity are inseparable. The stories shared by Métis participants demonstrate the ways that Métis culture is embedded into all aspects of life. Participants shared their personal and intergenerational journeys coming to understand and accept what it is to be Métis. They also shared specific aspects of their Métis identity—including land and location, community, family, culture and ceremony, and language—within the context of their personal wellness and experiences accessing health and social services in Victoria, BC.

Survivance and Reconnection With Identity

Participants shared many different journeys that they have had in understanding their Métis identities. A few noted that they have always known; they grew up being raised with strong Métis traditions—understanding who they are and where they come from—as one person said: “I do self-identify as Métis… that identification comes from my mom. She very much instilled that, that part of who we are in us, in all of us kids, but probably most especially in me” (plaanten).

More commonly, however, participants indicated that they were new to discovering or understanding their Métis ancestry and what it is to be Métis:

I am learning what it means to me. I only found out about seven years ago that we were Métis and in the past year is the first time I really like started exploring what that means. So, it’s kind of starting to mean a community of other people but it’s all these other connections that I didn’t know I had.

lii shaadroon

Being Métis is actually becoming more meaningful later in my life. Growing up I didn’t really… I mean I identified as Métis but it didn’t really mean anything outside of the word Métis. We didn’t have any cultural teachings or like ceremonies attached to growing up because we weren’t really immersed in culture.

li pisaanlii

Regardless of how “new” people were to learning about their Métis roots, cultural identity and connectedness was often framed within the context of recovering and ongoing learning:

I feel like I’m still learning about my identity… with that comes a lot of learning and a lot of reflection about my own life and my own upbringing and it’s started different conversations with my mom that we haven’t had before, so that’s been really neat. Sometimes hard.

enn rooz faroosh

Participants frequently spoke openly about the significance of internalized shame fostered within their families in relation to Métis ancestry and identity:

My family hid who we were for a very long time. So my grandfather very specifically would not allow us to talk about being Métis outside of our family. And it was only after he died that my grandmother said, “You can now say who you are” …. Of course it was a big part of that family story to keep quiet because it was about survival. And I interpreted my grandfather’s telling me never to discuss it outside of the family as internalized racism and shame. And I’m rewriting that story as my grandfather loved me and my grandfather was protecting me as opposed to my grandfather was ashamed. I’m not sure my grandfather was ashamed. He might have been. That’s possible because he did experience that racism and I know that. But I’m also not sure that that’s the only reason that he kept that story quiet.

lii groo zel

I think I was 13, sitting with my grandpa, and he was carving and he was saying to me how important it was that I know where it is that I come from and my family’s quite ashamed around their history and… and that definitely comes from the impacts of colonization and residential school because my great-grandma was sent to an orphanage and removed from the community, because she was always considered a half-breed.

li pchi boom

Some participants shared their honest reflections on the challenges they have experienced in terms of their cultural identity. In particular, they broadly spoke about the impacts of colonialism and assimilation on their identities:

For me as a Métis person, I didn’t have any sense of connection and no sense of identity and was completely disenfranchised and made to be really assimilated. Like basically, I am the result of assimilation… So, because of that, knowing your sense of identity or feeling a sense of belonging… you just don’t have it… I’m in the process or reclamation but I still am bearing the brunt of not having close ties and not having a sense of connection and feeling welcomed or wanted or a part of anything.

enn fleur di pwayzoon

In response to ongoing impacts of colonialism, Métis people are working hard to maintain and reclaim their Métis culture and identities. In particular, some peoples spoke beautifully about their processes of reclaiming identity, taking ownership of it through overcoming internalized shame:

To me, it means having more of a voice than the… than my ancestors have. And when I say that, I mean, like, my grandmother. She didn’t really identity and she wasn’t proud of who she was, and she really didn’t have much of a voice. So my mom’s had a little bit more, and I in turn have a little bit more. So it’s like taking ownership of that.

lii frayz

For many people, this journey of strengthening, reclaiming, and asserting Métis identity is a form of healing past, present and future generations of Métis people.

Land, Location, and Positionality

When describing themselves, participants often spoke about where their ancestors came from. In addition to sharing stories about the cities where they grew up, the Métis participants that we spoke with commonly located themselves on the Indigenous lands that they live on. Some spoke about aspects of their histories and responsibilities in relation to the land:

I think to me it means understanding my history and my lineage and my connection to these lands and my responsibilities as well… it means something different to everybody but for me it really means embracing culture and just using Métis history and culture as a way to kind of inform, understand myself and understand kind of where I’m at in my life and how the histories that have brought me to where I am today.

zayon faroosh

As Métis people, our relationship to the land has been shaped by displacement and disconnection. However, Métis women, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse people are also reclaiming these connections through cultural resurgence. Many of these Métis community members also spoke about the ways in which they are raising their children to have a renewed relationship with the land, and to understand their responsibilities to take care of the land:

I understand my own family Métis ancestry and some of the disconnection from culture and how that’s impacted my family through addictions and trauma. And so right now I think I’m in the process of reclaiming my identity in terms of relationship to land, by not necessarily land ownership but, like, land stewardship and trying to bring that back and raise my children around a deeper respect to Mother Earth.

Ii kors di shenn

As city-dwelling Métis, living in urban areas like Victoria, it can be more difficult to engage in our land-based practices. Some participants spoke about the need to travel outside the city to connect with the land.

I kind of took more to it and I was more interested in a lot of the things, like trapping and going out, you know, being away out in the country. So I’m a bit of a fish out of water in the city. I’ve got one foot always somewhere else.

plaanten

At the intersection of location and identity, several participants spoke about their experience of being Métis as one of “walking in two worlds.” For example, enn rooz faroosh shared their experiences of feeling “othered” or not belonging anywhere. Similarly, lii groo zel spoke about walking within and between two worlds: the mainstream society and their cultural ways of knowing. They strive for balance, but often feel “out of step.” They shared:

When I walk in dominant society, I always feel out of step. I always feel like not quite right, I’m not quite balanced, I don’t quite fit. I’m not happy. I’m not well. I’m just never settled. And when I am following the values of my ancestors, it’s like all is right in the world…. I feel like I can’t walk in both. That if I split myself between the two worlds, I am unbalanced and so the last number of years I finally stopped saying, you know what, I want to follow the values of my Aboriginal ancestors. I want to follow the values of my Métis ancestors. And, for me, that has always felt right to me. So I’ve always tried to live in harmony and balance for myself and that is a much more collective way of being. And that has always felt right to me and that has never been valued outside of where I am. So those dominant societal values that surround me, have always told me that that’s wrong and have always told me that I am less than for being that way. And I finally realized genetically I’m wired to be that way. It’s in my blood. It’s in my spirit. It’s in my ancestry. And I am happy and I want to reclaim that and I want to stop fighting that and understand. And I now understand where it comes from instead of thinking that I’m just less than because somehow I don’t fit into this dominant society. I think, “Yeah, damn right I don’t fit in to the dominant society. And, you know what? I don’t want to.”

lii groo zel

Culture, Language, and Ceremony

For many of the people that participated in this project, Métis identity also centres on our culture and ceremony. Participants spoke about participating in ceremony and cultural activities, and working with traditional medicines. One person spoke about the way that they found community through the sweat lodge:

It’s really hard not having a place where you could call home and you could go and talk about your feelings and be supported and held and loved and cherished for sharing your feelings. And that’s what you get when you go to sweat lodges. ’Cause you are loved and you are supported. I could say anything I wanted to in a sweat lodge and know that I’m still good and that all my relations are right beside me, supporting me.

la gratelle

Some people also shared how food is both an important aspect of culture and identity. They shared stories about learning to bake bannock with their grandparents, and in turn passing this knowledge onto their children.

Participants also spoke about the importance of Michif, and other Métis languages, as the foundation of cultural identity. Participants shared stories of the ways that their families would use and incorporate Michif in conversation:

So in our family we use Michif. We didn’t know we were using Michif but it would be funny because every time we would use a word in Michif, and my family’s francophone, I would say, “Well that’s not really a French word. Where does that word come from?” And my family would say, “It’s an old family word and we don’t talk about that outside of the family.”

lii groo zel

Métis cultural expressions through art and crafting were commonly discussed as an important part of our collective identities as Métis people. Some community members spoke about learning how to weave, to bead, and to tuft. Others described their relationship through appreciating the work of Métis artists and artisans.

Connection to Family and Community

For many, Métis identity also involves our connection to family and to our ancestors. Several people told beautiful stories about their grandparents and the strong relationships they had in their Métis families. Aen nipinet shared the importance of family connectedness: “Métis to me really is like family. So, my connection with my family members and my ancestors, its places being a way of living. It’s culture and it’s connection.” These stories often involved baking and cooking, and sharing food. They spoke about trying to remember or imagine what their ancestors’ lives would have been like, as well as honouring their ancestors in ways that made sense to them. For la haarroozh, connection represented ways of acknowledging their genealogy and “the journey of my ancestors and how I came to be.”

As well, connection to community is an incredibly important aspect of Métis identity. Many participants spoke about the importance of belonging, sharing stories about their ways of finding, strengthening, and maintaining their connections to the Métis community in Victoria, the Métis Nation of Greater Victoria. While some participants indicated that they did not have a particularly strong connection to the community, those who did noted that the community is vibrant, comforting, and accepting. One person shared how exciting it was to connect with the Métis community for the first time: “It was exciting because it was like this whole other community… that kind of just like accepted us and showed us what it meant to be Métis.” (sasperal)

Connecting to community can involve gathering, feasting, and visiting. For others, community connections involve acts of service and holding space for others to find their own connections:

I guess for me being Métis and looking at my family… right now it means a little bit of uncertainty but also lots of hopefulness because I am starting to discover different places to further learn and to connect with Métis culture and heritage.

li pisaanlii

At times, however, connection to community can be challenging through the presence of lateral violence and exclusion:

I do want to preface that I have met wonderful people in the Métis community, but as of recently it’s felt very exclusionary in certain circles… it would be nice to see Métis people being a little bit more inclusive, I think, to people who are Métis, but they’re outsiders, I guess.

enn fleur di pwayzoon

Throughout the conversations, when lateral violence was discussed, it was used to describe ways of criticizing, excluding, or attacking one’s own people. This was described as a manifestation of colonialism and oppression. Participants, like li pchi boom, shared reflections that an aspect of exclusion from the Métis community may be based on colonial perspectives:

I think being Métis is beautiful. It’s a combination of Indigenous ancestry and shared understanding with your ancestry - that developed in family anyway… unfortunately through the impacts of colonization but also through partnerships that were based on kinship and reciprocity and love, so they were really beautiful relationships in my family, and it’s something that I resonate quite strongly with because of the practices that have been passed down within my family, and some of the teachings. And, unfortunately, it’s something I don’t always like to disclose because of cultural gatekeepers and the understanding of where Métis is and my Métis family originates on the West Coast, not in the Red River, where I think there’s always this assumption that’s created that people have to be from there in order for Métis Settlements to have existed. And I have met Métis folks across the country who have disclosed that they are Métis, who have felt a lot of lateral violence in communities and have had the same hesitation that I have to talk about it. And that being said, I do have registration as a Métis person in local community.

li pchi boom

Lii groo zel also shared how they see lateral violence having stemmed from the harms of colonialism. Through healing these harms, the Métis community can once again focus on traditional values and ways of caring for one another:

Amongst ourselves, we need to care for each other better. And I think we can and I think we’re trying and I think we still have greater work to do. And so, I think, for me, that’s where my hope is, is that if we can use this to be honest with each other and say, you know, intent and affect are two different things. Right? That our intention is to walk in a good way and sometimes our affect is that we’re still hurting each other even when we’re intending to do good, that we’re still carrying some of that baggage. So, can we look at that? And can we… can we look at that in a way where we’re not shaming each other? Can we do that in a way where we’re not creating more violence toward each other? And can we figure out how we can do this differently so that we can have safer spaces? Because I really love the health and wellness [programs]. I would love to go to more of those things. But, honest to God, sometimes I have to decide; it’s like am I going to go to the drumming workshop? Or am I too scared today because I just don’t have the reserves because someone’s going to be an ass during that time, right?

lii groo zel

Discussion

Métis people are survivors of historical and ongoing colonialism. The literature has detailed the many ways in which colonial attempts at assimilation have disrupted the foundations and maintenance of Métis ways of knowing and being (Auger, 2021b, Edge & McCallum, 2006). This has included, but is not limited to, Canada’s ongoing legacy of dispossession and denial of the Métis people. Despite these ongoing systemic challenges, Métis people have demonstrated their resistance and resilience. Continual and intentional work is required for Métis people to heal, while strengthening cultural capital and continuity. As Métis scholar Kim Anderson (2000) aptly notes, “Identity recovery for our people inevitably involves the reclaiming of tradition, the picking up of those things that were left scattered along the path of colonization” (p. 157). This statement seemingly resonates throughout the findings from this research, which illustrate the powerful process of reconnecting with Métis identity. In many families, Métis ancestry and identity was commonly hidden for protection and other reasons (Richardson, 2006). Métis people’s histories and experiences with colonialism, along with our unique strategies for protecting our families, have created shared stories of survival throughout a period of invisibility (Logan, 2015). Of course, this is not the story of all Métis families, as others shared their families’ journeys of intergenerational resistance and bravery, through continually asserting their cultural identities despite threat of persecution.

During the 2017 Daniels Conference: In and Beyond the Law at the Rupertsland Centre for Métis Research, University of Alberta, Métis Elder Maria Campbell shared her perspective around identity:

We never talked about identity and all of those types of things. I realize those are important but that’s not what I’m here to talk about. I just want to say that what is wrong with many tribes? There’s Métis from Red River. What’s wrong with Métis from someplace else; it’s okay for every other Indigenous Nation in this country to have dialects and different territories that we belong to. Why do we have to be the way that we are? Why does somebody have to tell me that I’m not Michif and I don’t speak Michif because I speak Cree? Most of the old men that I worked with spoke Cree first and considered themselves Indians, not Indians in the way we think in White Man’s terms because that’s how most of us think. We were Indians because we were people of the land, and that’s what that meant. My father called himself an Indian, but he always said, “I’m Michif. I’m a Halfbreed,” after, and he meant that he had always lived off the land. And there’s a whole different thing, when people start thinking and having all of these discussions, they are thinking in colonial western terms, and that’s what we have to stop doing.

The historic Daniels Decision in 2016, which ruled that Métis and non-status Indians are Indians under the Constitution Act, 1867, found that there is no need to place a legal definition for the word “Métis.” Despite this, however, some elected Métis leaders continue to argue for continual use of boundaries, contributing to ongoing issues with Métis identity politics. Beyond issues in the politic arena, identity politics impact Métis people’s wellness; threads of this story were shared by participants in the present research study as well as in previous writing on Métis women’s identity journeys. For instance, Leclair and Nicholson (2003) share, “As Métis women, our path to self-realization can be hindered by people within our own communities. There are some who do not want to offer us the recognition and place we need. Others are living out the patriarchal legacy of our colonial past” (p. 62). Unquestionably, colonialism has intentionally infiltrated the ways in which we conceptualize our identities as Métis and First Nations people. Colonial recognition vis-à-vis the Indian Act, as well as in/exclusion in historic and contemporary treaties, serve to fracture individual and collective identities among Indigenous peoples—thereby challenging solidarity and kinship connections between Métis and First Nations. And while Métis are largely exempt from the Indian Act, Métis identity politics are highly impacted by colonial recognition politics through patriarchal notions and court decisions on who does (not) belong. In order to contribute to decolonizing our thinking around identity, we assert the need to return to our teachings, which have long been upheld by powerful knowledge keepers, Elders, and matriarchs across Métis communities.

Participants in the present study spoke eloquently about recognizing their connection to land and their location in Victoria, BC—on unceded territory of the Lək’wəŋən -speaking peoples. As authors living on Lək’wəŋən territory (MA, RM), and elsewhere (CJ, WP), we echo the words of our community members with respect to our gratitude to the original and ongoing caretakers of this land. We seek to understand our historical and ongoing responsibilities to be good relatives and neighbours as we seek to fulfil our relational obligations to the Lək’wəŋən people. In sharing the story of The Woman Who Married a Beaver, Metis scholar Brenda MacDougall (2018) highlights the role of collectivism in understanding Métis identity, where kinship, family, community are prioritized over any one individual. Our relationships are central to understanding who we are, as identity falls at the intersection of our individual characteristics, our families, our communities, our languages, our connection to land, our knowledge systems, and our spirituality (MacDougall, 2018). It is also well documented that community connectedness and cultural identity are central to health promotion for Indigenous peoples (Goudreau et al., 2008; Howell et al., 2016). Stewart (2007) illustrates the importance of utilizing Indigenous approaches to helping and healing, rooted in culture, ceremony, Elders’ guidance, storytelling, and connectedness to family and community. Similarly, as Jones et al. explain (2020), Métis women and girls have always used and upheld matrilineal kinship networks as a way of sharing healing knowledges, which contribution to collective wellbeing and safety. As demonstrated by the participants in this research, Métis wellness is rooted within our ways of knowing and being, with support from our families, Elders, ancestors, and communities. As we reflect on the knowledge shared throughout these conversations, we are reminded of how Métis women, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse peoples’ stories are medicine; and we, as a research team, felt honoured and uplifted through the process of working through these stories and knowledges and sharing them in the context of Métis identity.

Limitations

This research was conducted during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Recruitment was conducted online, through social media, and we recognize that not all Métis people in Victoria, BC have social media accounts. While word of mouth also may have contributed to informal recruitment, the period of time between the poster being shared online and when we reached beyond capacity for participation was a couple of weeks. With cost savings due to the inability to travel to conduct interviews, we were able to increase our capacity for interviews (from 15 to 24). However, it is likely that there were even more people who were interested in participating than we had capacity to interview. While our sampling was random—based on interest—the Métis participants (n=24) may not be representative of the entire Métis community in Victoria, BC, with a population of more than 6500 (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Conclusion

As a result of violent colonial policy and practice, Métis people’s identities have been challenged—and in some cases fractured (Auger, 2021b; Monchalin, 2020). While narratives around Métis wellness have often focused on family and community deficits, the stories and healing knowledges shared in this research suggest that we return to looking at what makes us, as Métis people, well. In order to reclaim and heal our identities, we can turn to the strengths of our families and ancestors, our culture and ceremonies, and our Elders and communities. We also can dedicate our time to ensuring that the future generations—the present and future children and youth across Métis communities—are raised with a sense of pride and responsibility in what it means to be Métis. In Victoria, BC, this includes a strong understanding of our responsibility to the Lək’wəŋən-speaking peoples who have cared for this land since time immemorial.

Appendices

Note

-

[1]

Her name was Suzette, Susan, or Josephine Jollibois, depending on the record source and the Nisga’a Nation is currently helping me to truly understand who my ancestors are as a process of coming home

Bibliography

- Absolon, K. (2011). Kaandossiwin: How we come to know. Fernwood Publishing.

- Absolon, K. & Willett, C. (2005). Putting ourselves forward: Location in Aboriginal research. In L. Brown & S. Strega (Eds.) Research as resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches (pp. 97–126). Canadian Scholar’s Press.

- Anderson, K. (2000). A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood. Sumach Press.

- Auger, M. D. (2016). Cultural continuity as a determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ health: A metasynthesis of qualitative research in Canada and the United States. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2016.7.4.3

- Auger, M. D. (2021a). “The strengths of our community and our culture”: Cultural continuity as a determinant of mental health for Métis people in British Columbia, Canada. Turtle Island Journal of Indigenous Health. (In press)

- Auger, M. D. (2021b). Understanding our past, reclaiming our culture: Métis resiliency and connection to land in the face of colonialism. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 10(1), 1–28.

- Barkwell, L. (2008). Metis infantry: The Victoria Voltigeurs (Infantrymen). Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research: Victoria Museum of Métis History and Culture. https://www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/07418

- Burley, D. G. (2014). Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s lost Métis suburb, 1900–1960. Urban History Review, 42(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.7202/1022056ar

- Campbell, M. (2017, January). Panel 1: Daniels in Context. Presentation at the Daniels Conference: In and Beyond the Law.

- Chartrand, C., L., A., H. (2007). Niw_Hk_M_Kanak (“All My Relations”): Metis-First Nations relations. National Centre for First Nations Governance.

- Christie-Peters, Q. (2016). Anishinaabe art-making as falling in love: Reflections on artistic programming for urban Indigenous youth. University of Victoria.

- Daniels v.6 Canada (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada) (2016), 2016 SCC 12, 1 SCR 99.

- Flaminio, A. C., Gaudet, J. C., & Dorion, L. M. (2020). Métis women gathering: Visiting together and voicing wellness for ourselves. AlterNative, 16(1), 55–63.

- Flicker, S. & Nixon, S. (2014). The DEPICT model for participatory qualitative health promotion research analysis piloted in Canada, Zambia and South Africa. Health Promotion International, 30(3), 616–624.

- Gaudet, J. C., Dorion, L. M., & Flaminio, A. C. (2020). Exploring the effectiveness of Métis women’s research methodology and methods promising wellness research practices. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 15(1), 12–26.

- Goudreau, G., Weber-Pillwax, C., Cote-Meek, S., Madill, H., Wilson, S. (2008). Hand drumming: Health-promoting experiences of Aboriginal women from a Northern Ontario urban community. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 4(1), 72–83.

- Goulet, G. & Goulet, T. (2008). The Métis in British Columbia: From fur trade outposts to colony, FabJob Inc.

- Greenwood, M. L. & de Leeuw, S. N. (2012). Social determinants of health and the future well-being of Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatric Child Health, 17(7), 381–384.

- Howell, T., Auger, M., Gomes, T., Brown, L., & Young Leon, A. (2016). Sharing our wisdom: An Aboriginal health initiative. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 11(1), 111–132. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ijih/article/view/16015

- Jones, C., Monchalin, R., Bourgeois, C., & Smylie, J. (2020). Kokums to the Iskwêsisisak: COVID‑19 and urban Métis girls and young women. Girlhood Studies, 13(3), 116–132, http://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2020.130309

- Kovach, M. (2010). Conversational method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 40–48.

- Lawrence, B. (2004). “Real” Indians and others mixed-blood urban Native peoples and Indigenous nationhood. University of British Columbia Press.

- Leclair, C. (2002). Memory alive: Race, religion, and Métis identities. Essays in Canadian Writing, 75, 159–176.

- Leclair, C & Nicholson, L. (2003). From the stories that women tell: The Métis women’s circle. In K. Anderson & B. Lawrence (Eds.), Strong Women Stories (pp. 55–69). Sumach Press.

- Legault, G. (2015). Mixed messages: Deciphering the Okanagan’s historic McDougall family. Canadian Archaeological Association, 39(2), 241–256.

- Logan, T. (2015). Settler colonialism in Canada and the Métis. Journal of Genocide Research, 17(4), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.10080/14623528.2015.1096589

- Macdougall, B. (2017). Land, family and identity: Contextualizing Metis health and well-being. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/context/RPT-ContextualizingMetisHealth-Macdougall-EN.pdf

- Macdougall, B. (2018). Knowing who you are: Family history and Aboriginal determinants of health. In M. Greenwood, S. de Leeuw, & N. M. Lindsay (Eds.), Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: Beyond the social (2nd ed.) (pp. 127–146). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Monchalin, R., Smylie, J., Bourgeois, C. & Firestone, M. (2019). “I would prefer to have my health care provided over a cup of tea any day”: Recommendations by urban Métis women to improve access to health and social services in Toronto for the Métis community. AlterNative 15(3), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180119866515

- Monchalin, R., Smylie, J., & Bourgeois, C. (2020). “It’s not like I’m more Indigenous there and I’m less Indigenous here.”: Urban Métis women’s identity and access to health and social services in Toronto, Canada. AlterNative, 16(4), 323–331. https://doi.org/101177/1177180120967956

- Newhouse, D., & Peters, E. (2003). Introduction. In D. Newhouse & E. Peters (Eds.), Not Strangers in These Parts: Urban Aboriginal Peoples (pp. 5–13). http://policyresearch.gc.ca/doclib/AboriginalBook_e.pdf

- Peters, E. J. (2011). Emerging themes in academic research in urban Aboriginal identities in Canada, 1996–2010. aboriginal policy studies, 1(1), 78-105. https://doi.org/10.5663/aps.v1i1.9242

- Richardson, C. (2006). Métis identity creation and tactical responses to oppression and racism. Variegations, 2, 56–71.

- Richardson, C. (2016). Belonging Métis. JCharlton Publishing.

- Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. (2013). “The people who own themselves”: Recognition of Métis identity in Canada. Parliament of Canada. http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/411/appa/rep/rep12jun13-e.pdf

- Statistics Canada. 2017. “Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Key Results from the 2016 Census.” Statistics Canada. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/dailyquotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm.

- Stewart, S. (2007). Indigenous helping and healing in counselor training. Centre for Native Policy and Research Monitor, 2(1), 53–65.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods (6th ed.). Fernwood Publishing.

List of tables

Table 1

Michif medicines used as participant pseudonyms