Abstracts

Abstract

The high numbers of Aboriginal children placed in provincial and territorial care demonstrate the need for effective interventions that directly address the legacy of trauma from colonialization. This paper argues that healing is a critical component of any intervention seeking to help Aboriginal Peoples and their children. Research on healing and recent government initiatives and legislation directed at preserving traditional Aboriginal healing practices are discussed. This article concludes with recommendations for various community members involved in the healing of Aboriginal Peoples.

Keywords:

- healing,

- child welfare,

- traditional healing practices

Article body

Introduction

It has been documented that even before the first treaties were signed, Aboriginal peoples had the ability and collective will to determine their own path in all aspects of their culture and had control over their own political, economic, religious, familial, and educational institutions (Keeshig-Tobias & McLaren, 1987; Lee, 1992).[2] Years of colonialization have led to the devastation and almost complete genocide of Native culture (Lee, 1992; Patterson, 1972; Red Horse, 1980). Residential schools operated in Canada, opening as early as 1894, with the last remaining residential schools closing in 1984 in British Columbia (Barton, Thommasen, Tallio, Zhang, & Michalos, 2005) and in 1996 in Saskatchewan (Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 2003).[3] Approximately 20 to 30 percent (approximately 100,000 children) of Aboriginal Peoples attended residential schools (Thomas & Bellefeuille, 2006). Numerous residential school staff across Canada have pleaded guilty to various types of sexual, physical, psychological, and spiritual abuse towards Aboriginal children placed in their care (Gagne, 1998; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples [RCAP], 1996b). Many children also died from preventable diseases (Milloy, 1999; Trocmé, Knoke, & Blackstock, 2004). Gagne (1998) proposed that most of the family violence, alcoholism, and suicidal behaviour among First Nations citizens originated either directly or indirectly from the abuse suffered by residential school students.

Residential schools do not only have effects on the students who attended but also their children and their grandchildren (Gagne, 1998). Barton et al. (2005) examined differences in quality of life between Aboriginal residential school survivors, Aboriginal non-residential school attendees, as well as non-Aboriginal Bella Coola Valley residents. Based on a sample of 687 residents from the Bella Coola Valley area in British Columbia, Canada, the researchers conducted a retrospective review. Data obtained from 33 questions in the 2001 Determinants of Health and Quality of Life Survey was examined, utilizing a series of descriptive, univariate, and Pearson Chi-square analyses. Aboriginal participants included 47 (27%) residential school survivors and 111 (63%) non-residential school attendees. Ten percent of participants did not answer this question (Barton et al., 2005).

Statistically significant differences emerged between Aboriginal Peoples and non-Aboriginal peoples concerning the overall quality of life (p = 0.05). It is important to note that both Aboriginal residential school survivors and Aboriginal non-residential school attendees reported statistically significantly poorer health on most of the outcomes measures, compared with non-Aboriginal peoples. These results demonstrated the intergenerational pervasiveness of the residential school experience. The authors of this study suggested that Aboriginal residential school survivors may have a higher prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Barton et al., 2005). This suggestion is validated by research that has found that approximately two-thirds of Aboriginal Peoples have experienced trauma as a direct result of the residential school era (Manson, 1996; 1997; 2000).

Yellow Brave-Heart (2003) identified various effects of PTSD. Possible effects include, but are not limited to, the following: identifying with the dead; depression; psychic numbing; hypervigilance; fixation to trauma; suicide ideation and gestures; searching and pinning behaviour; somatic symptoms; survivor guilt; loyalty to ancestral suffering and the deceased; low self-esteem; victim identity; anger; distortion and denial of Native genocide; re-victimization by people in authority; mental illness; triggers, flashbacks and flooding; fear of authority and intimacy; domestic and lateral violence; inability to assess risk; and re-enactments of abuse in disguised form.

Residential schools and the trauma that was experienced has been described as a “de-feathering process,” stripping Native Peoples of their knowledge, spirituality, physical and emotional well-being, and most sadly, has led to the loss of community (Locust, 2000). Native Peoples’ connection with the spiritual, emotional, physical, and mental realms has been abruptly and chronically disrupted (Locust, 2000). Gagne (1998) hypothesized that colonialism is at the root of trauma because it has led to the dependency of Aboriginal Peoples to settlers and then to cultural genocide, racism, and alcoholism.

This trauma is associated with Aboriginal Peoples’ loss of culture. Aboriginal Peoples were forced to relinquish something valuable – cultural identity – that is difficult, if not impossible, to regain (Ing, 1991). In the residential school system, Aboriginal children were forbidden to speak their own languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or maintain their cultural traditions (Trocmé et al., 2004). Oral transmissions of child-rearing practices and values were also lost as a result of suppressed language (Gagne, 1998; Ing, 1991). Residential school included parenting models based on punishment, abuse, coercion, and control. Children in residential schools did not experience healthy parental role models and without appropriate parenting models, many Aboriginal parents lacked the necessary knowledge to raise their own children (Bennett & Blackstock, 2002; Grant, 1996).

The devastating effects of this loss of culture can be seen in the high numbers of Aboriginal children who are removed from their homes and placed in provincial care. The United Nations has stated, “Indigenous children continued to be removed from their families by welfare agencies that equated poverty with neglect” (United Nations, 2003, p. 5). In British Columbia, the number of First Nations children in care increased from a total of 29 children in provincial care in 1955 to 39% of the total number of children in care in 1965 (Kline, 1992). By 1977, 20% (15,500) of children in care across Canada were First Nations (Hepworth, 1980). The highest numbers of First Nations children in care appear in the western provinces, specifically in British Columbia (39%), Alberta (40%), Saskatchewan (50%), and Manitoba (60%) (Hudson & McKenzie, 1981). In 1981, 85% of children in care in Kenora, Ontario, were First Nations. First Nations only make up 25% of the population in Kenora. In this study, it was determined that status Indian children were placed in care at a rate of 4.5 times than that of other children in Canada (Kline, 1992). By the end of 1999, 68% of children in provincial care were First Nations (both status and non-status) (Farris-Manning & Zandstra, 2003). Unfortunately, Indian children are less likely to be adopted (Hudson & McKenzie, 1981; Kline, 1992). According to the Department of Indian Affairs, over 11,132 children of Indian status were adopted between 1960 and 1990 (RCAP, 1996b). This does not include all other types of non-Status Indian children. It has been documented that as low as 2.5 percent of Aboriginal children are placed in race-matched families (Blackstock & Bennett, 2003).

It is estimated that there are currently over 25,000 Aboriginal children in child welfare systems across Canada (Blackstock, 2003). This is approximately three times the highest enrolment figures of the residential school in the 1940s (Philp, 2002). Between 2000 and 2002, approximately 76,000 children and youth were placed in provincial/territorial care (Farris-Manning & Zanstra, 2003). Thirty to 40 percent of children in care are Aboriginal (Blackstock & Bennett, 2003) when less than 5% of the total children in Canada are Aboriginal (Statistics Canada, 1996). Between 1995 and 2001 the number of Status Indian children entering into care rose 71.5% across Canada (McKenzie, 2002). The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child specifically raised concerns regarding the disproportionate risks faced by Aboriginal children in Canada and urged the Canadian government to eliminate all forms of inequalities (United Nations, 2003).

Although lengthy, the introduction of this paper has been used to demonstrate how colonization and forced cultural assimilation of Aboriginal Peoples, through the use of residential schools and then child welfare, has taken a substantial toll on Aboriginal communities across Canada. This is evidenced by the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in care (Blackstock & Trocmé, 2005; Trocmé et al., 2001). The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that healing is an essential component of any intervention aimed at improving the lives of Aboriginal Peoples and their children. As schools of social work in Canada work towards providing interventions that are evidence-based, it is important to consider evidence and science from the perspectives of Aboriginal Peoples. I will begin with a brief discussion of the concept of knowledge and a comparison of Aboriginal and Western scientific practices. Following this discussion, qualitative research regarding the effectiveness of traditional healing practices will be presented. Various legislative impacts on the protection of traditional knowledge will also be discussed. This paper concludes with brief recommendations for the federal and provincial governments, professional associations and organizations, academic institutions, and various health care providers.

Knowledge and Evidence

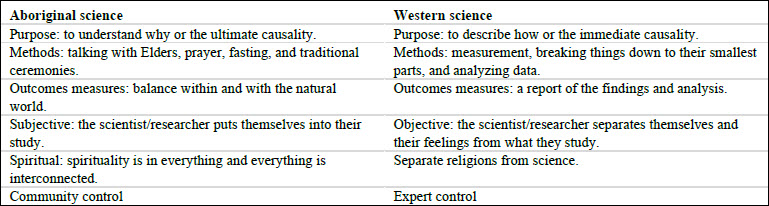

Battiste and Youngblood Henderson (2000) defined knowledge in the Report on the Protection of Heritage of Indigenous People as “a complete knowledge system with its own epistemology, philosophy, scientific and logical validity . . . the plurality of Indigenous knowledge engages a holistic paradigm that acknowledges the emotional, spiritual, physical, and mental well-being” (p. 41). The authors claimed, “Traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous people is scientific; in the sense it is empirical, experimental, and systematic” (p. 44). Aboriginal perspectives on knowledge differ in two important respects from Western science: it is highly localized (geographically) and it is social. The focus of Aboriginal science is the web of relationships between humans, animals, plants, natural forces, spirits, and landforms in a particular locality, as opposed to the discovery of universal laws (Battiste & Youngblood Henderson, 2000). The following chart (Table 1) notes some important differences between Aboriginal and Western science. There are considerable differences in regards to the purpose of research, methodologies, outcome measures utilized, and issues pertaining to control and ownership of research. While keeping these differences in mind, it is important to remember that the diversity of Indigenous Peoples’ cultures, histories, and knowledges should not be a barrier but used as an opportunity to demonstrate the strength of plural knowledges in contemporary contexts (Martin Hill, 2003).

D. Dubie (personal communication, 2007), founder of Healing of the Seven Generations in the Kitchener/Waterloo area, wrote a grant proposal requesting funding for Aboriginal healing programs. The requested document, which she submitted to the federal government, had a section for “evidence”. The “evidence,” from a Western perspective, was likely looking for numbers, data, and statistical analysis of findings. D. Dubie wrote, “I’m sorry it would take me years and years to explain to you how healing works and how we know it works . . . you will just have to take my word” (D. Dubie, personal communication, 2007). This quote represents the complexity of the study of healing and its associated practices. Her proposal was successful and in 1998, the Government of Canada established a $350 million fund that is administered by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, operated by Aboriginal Peoples (Department of Justice, 2005).

Table 1

Healing

Aspects of healing are closely guarded by oral traditions and specific techniques are received directly from Elder healers, from spirits encountered during vision quests, and as a result of initiation into a secret society. It is believed that to share healing knowledge indiscriminately will weaken the spiritual power of the medicine (Herrick & Snow, 1995, p. 35). The Aboriginal Healing and Wellness Strategy (AHWS) provided a framework that can be used in developing community-appropriate guidelines for traditional healing programs. The AHWS does not support the recording or documentation of the practices of Healers, the medicines, the ceremonies, and the sacred knowledge for any purpose (AHWS, 2002). This is done in order to preserve the integrity of sacred knowledge and out of respect for the practitioners who hold this wisdom.

Community members have stated that healing work needs to be intimately aligned to relationships with Elders and other cultural leaders, as well as ceremonies and protocols designed for personal development (Lane, Bopp, Bopp, & Norris, 2002, pp. 2-3). Western/European interventions of mental health have been identified as generally ineffective in responding to the needs of Aboriginal Peoples (McCormick, 1997; O’Neil, 1993; Warry, 1998). It is also well documented that Aboriginal Peoples avoid using mainstream mental health services (McCormick, 1997) and have unusually high dropout rates when such services are utilized (Sue, 1981). Healing is an essential component in addressing the fact that both the federal and provincial governments have inflicted Aboriginal Peoples with many various forms of systematic abuse and discrimination, over several generations, in an attempt to assimilate Aboriginal Peoples into the dominant society through education, religion, law, and theft of land (Morrissette, McKenzie, & Morrissette, 1993; Waldram, 1990).

Aboriginal Peoples argue that supporting and enhancing Aboriginal culture is a prerequisite for positive coping (Peters, 1996). This process of regaining our cultural heritage is essential for survival. Our ancestors have prescribed interventions for many generations and these teachings need to be revived and integrated into current practices. It is essential that we are able to get in touch with our Indigenous identities and ways of being in the world. Until traditional Indigenous therapies are implemented and considered legitimate, there will remain the struggle and suffering of a historical legacy and ongoing trauma will continue (Duran, Duran, Yellow Horse Brave Heart, & Yellow Horse-Davis, 1998). The Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2007) believed that culture is the best medicine.

Research on Healing

The best available evidence for Aboriginal healing is derived from qualitative studies. Thomas and Bellefeuille (2006) conducted a formative qualitative study exploring a Canadian cross-cultural Aboriginal mental health program in Winnipeg, Canada. A recruitment notice was circulated among Aboriginal organizations inviting people, who had prior residential school experience, within the city to participate. Methods utilized were conversational-style interviews (non-scheduled format) and a focus circle/group. Traditional Aboriginal healing circles and focusing (a psychotherapy technique comprised of self-awareness and empowerment practices) were the interventions being evaluated. Traditional healing circles refer to the coming together of Aboriginal Peoples for the purpose of sharing their healing experiences and to further their healing journey (Heilbron & Guttman, 2000; Latimer & Cassey, 2004). Focusing refers to a body-based awareness technique that involves turning one’s attention to the various sensations of the body. It allows people the opportunity to be safe observers of their bodily experiences of trauma and to experience this sensation at their own pace (Gendlin, 1996).

Results demonstrate that the traditional healing circle created a safe environment for the participants, emphasized the sacredness of each story shared, and gave the opportunity, to each of its members, to share without being interrupted. Storytelling, teaching, and sharing within healing circles promoted a spirit of equality in the counselling relationship, empowered the participants, and eliminated hierarchy. Focusing was found to be effective in helping people to overcome self-criticism, overcome feelings of being stuck in life, deal with unsure feelings, get what they are seeking from within themselves, better handle emotions, shift out of old routines, and deal with past traumatic events. It was suggested that focusing could be appropriate for Aboriginal Peoples, as it is a humanistic, person-centred approach to healing, which reflects the core values of respect and non-interference (Thomas & Bellefeuille, 2006).

Kishk Anaquot Health Research collected data from participants of various healing projects funded by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation from September 2002 to May 2003. They utilized a national survey, individual questionnaires, and focus groups. Participation requests were sent out to active grants projects and 826 participants from 90 different healing programs across Canada responded. Challenges affecting more than half of the participants in this study were: denial; grief; history of abuse as a victim; poverty; and addictions (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2003). Western interventions identified as helpful were: individual, group, couples, and family therapy; art therapy; narrative therapy; attachment theory; and genograms. Traditional interventions included sharing circles, sweats, ceremonies, fasting, Métis wailers, and traditional teachings. Alternative interventions were also noted, such as energy release work, breath work, and acupuncture (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2003, p. 68). It was stressed that these various approaches were balanced and/or used simultaneously (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2003, p. 95). This literature suggests that a choice of intervention approaches be offered, with the flexibility to meet special needs.

The participants of this in-depth study identified individual therapy sessions as helpful to improving their self-esteem and finding personal strengths. Individuals found healing programs helpful in the following ways: ability to handle difficult issues (71%, n = 726); ability to resolve past trauma (75%, n = 726); ability to prepare for and handle future trauma (78%, n = 731); and ability to secure family supports (64%, n = 675) (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2003). The most helpful aspects of healing programs were: Legacy education, opportunities for learning (specifically, relationship skills and processing intense emotions), bonding or connecting with other participants, and cultural celebration. Legacy education refers to information regarding residential schools and has been noted for its particular usefulness as it “explains that the reactions to the residential school experience are normal and predictable consequences of institutional trauma and not an individual character flaw or weakness” (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2003, p. 76).

The focus group participants also identified several key characteristics of a healer: a good track record of ethical conduct supported by references; humble; honest; gentle; has worked through their anger; are recognized by others as a healer; listens intently; hears clearly; has reconciled with mother earth; absolute self-acceptance; respected in the community; fearless; free from the need to control; understands professional limitations and makes referrals; and is spiritually grounded (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2003).

Duran and Duran (2000) conducted a study using a combination of culturally-based dream interpretation and Western psychotherapy techniques. First Peoples found these techniques to be helpful in treating PTSD symptoms, with a focus on how they are transmitted across generations. The most promising aspect found was reconnecting clients with their Native identity, which improved self-esteem and sense of identity, which, in turn, was correlated with healthy functioning (Duran & Duran, 2000, p. 89). Within counselling, clients are helped to reconnect with their culture, as well as to understand and cope within the dominant white environment, while still maintaining their cultural sense of identity (Duran & Duran, 2000).

Chandler and Lalonde (1998) examined cultural continuity as a protective factor against suicide among First Nations Peoples. Six factors of cultural continuity were examined: evidence of self-government; evidence that bands had tried to secure Aboriginal title to their traditional lands; the majority of students attend a band-run school; band-controlled police and fire services; band-controlled health services; and established cultural facilities. Data for the study was taken from suicide information (both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) and was gathered from several sources: Statistics Canada, the British Columbia Ministry of Health, Health Welfare Canada, the Canadian Centre for Health Information, Indian Registry, and the Band Governance Database from Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. They hypothesized that when communities have a strong sense of their own historical continuity and identity, vulnerable youth have access to resources in the community that acts as a buffer in times of despair. Therefore, in communities where cultural transmission has been disrupted, vulnerable youth may be at increased risk of suicide due to the lack of such buffers (Chandler & Lalonde, 1998). The researchers found that the rate of suicide was strongly associated with the level of these factors. They discovered lower suicide rates where efforts were being made within the community to preserve and rebuild their culture. Communities with all of the cultural continuity factors had no suicides, while those with none had significantly higher suicide rates (p = .002). They noted that there is no clear reason to label death as a suicide and therefore, deaths are typically recorded as accidental (Chandler & Lalonde, 1998). Accidental death rates are substantially higher within First Nations populations. This suggests a massive underestimation of true suicide rates.

Brave Heart-Jordan (1995) conducted a group intervention among the Lakota, with the primary purpose of grief resolution and healing. Key features of this intervention are congruent with treatment for Holocaust survivors and descendants. Catharsis, abreaction, group sharing, testimony, opportunities for expression of traditional culture and language, and ritual and communal sharing were included in the intervention model. Results demonstrate that 100% of participants found the intervention helpful in the area of grief resolution and felt better about themselves after the intervention. Ninety-seven percent of participants were able to make constructive commitments to memories of their ancestors following the intervention. Seventy-three percent of participants rated the intervention as very helpful (Brave Heart-Jordan, 1995).

It has been found that healers help clients overcome their fear of change, help to clarify their vision, and strengthen their motivation. It was also found that no specific healing technique was better than another but rather appeared to be a vehicle for giving clients the power to access something they already possess (Carlson & Shield, 1990).

Davis-Berman and Berman (1989) conducted an evaluation of wilderness camps and found participation in the camps to foster a strong sense of cultural pride, renew a sense of belonging, and increase trust in relationships. Wilderness camps address physical, spiritual, emotional, and mental aspects of the lives of the youths who attended. These camps were found to foster increased self-esteem in participants because these programs are flexible and diverse, allowing every participant to find a different activity in their area of strength (Davis-Berman & Berman, 1989).

Fuchs and Brashshur (1975) found that Native Peoples believe that Western medical care treats the symptoms of the disease but does not deal with the cause (p. 918). Two hundred and seventy-seven families were interviewed and completed the survey and 170 families (33%) who completed the survey were not interviewed, due to a variety of factors. Results demonstrate that one-third of Native families (in a United States-random sample) used traditional Native medicine in combination with the use of modern Western medicine. A strong relationship between the use of traditional medicine and returning to the reserve was found and it was suggested that this association reflects an unmet need for traditional Aboriginal medicines in urban areas (Fuchs & Brashshur, 1975). Suggestions are made for urban centers to preserve Native culture and promote the availability of traditional health treatments (Fuchs and Brashshur, 1975, p. 925).

Traditional healing practices have also been found to have profound effects on individuals who have sexually offended in the community. For example, counsellors taking part in traditional healing practices with Aboriginal men reported an increased openness to treatment, an enhanced level of self-disclosure, and a greater sense of grounding or stability. “Having attended sweats, I do know that during the ceremony people are able to talk about their own victimization because of the safe and secure nature of the Sweat” – the quote is an expression from a therapist (Solicitor General Canada, 1998, p. 76).

There is a diverse range of traditional healing practices that have roots in Indigenous values and cultures. Some core values of healing practices (holism, balance, and connection to family and the environment) are common to Aboriginal worldviews across cultures, while others are clearly rooted in local customs and traditions. For Indigenous peoples, the concept of holism extends beyond the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual aspects of individual lives and includes relationships with families, communities, the physical environment, and the spiritual realm. These values are seen in traditional interventions in Greenland, Australia, and the United States of America (Archibald, 2006, pp. 39-53). Over time, some of these practices have grown to incorporate Western values and practices. It has been well documented that a cross-cultural approach will allow for both traditional Western clinical practices and Aboriginal healing practices (Culley, 1991; Graveline, 1998; McGovern, 1998; Thomas & Bellefeuille, 2006).

The Aboriginal Healing Foundation published a report of the history of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada in order to enable a future in which Aboriginal people have fully addressed the legacy of historical trauma suffered in the residential school system (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2006). The Foundation stated that healing is a long-term process that occurs in stages. They projected that it takes an average of ten years of sustained work for a community to reach out to individuals and create a trusting and safe environment while disengaging denials of the past and engaging participants in direct therapeutic healing. Healing goals are best achieved through services provided by Aboriginal practitioners and long-term involvement in a therapeutic setting. Participants of services provided by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation rated Elders, healing and talking circles, and traditional ceremonies and practices as the most effective. During a discussion with the commissioners of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), Orten (as cited in Peters, 1996) elucidated the relationship between culture and healing with this quote:

Recovering our identity will contribute to healing ourselves. Our healing will require us to rediscover who we are. We cannot look outside for self-image; we need to rededicate ourselves to understanding our traditional ways. In our songs, ceremony, language and relationships lie the instructions and directions for recovery

p. 320

For many Aboriginal Peoples, healing means addressing approaches to wellness that draw on culture for inspiration and means of expression (Thomas & Bellefeuille, 2006).

The Aboriginal Healing Foundation provided detailed information on best healing practices and stated that healing and reconciliation are central to First Peoples’ ability to address other pressing social issues and to move to better relationships (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2007). Traditional healing practices have demonstrated effectiveness and should be incorporated in all possible interventions involving First Peoples and their children. These practices should be evident in both professional practices and in the development of social policies.

Legislation: Aboriginal Culture and Research

Protection and promotion of existing knowledge

In January 1998, as part of its response to the report of the RCAP, the Government of Canada issued a Statement of Reconciliation. This document acknowledged the contributions made by Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples to the development of Canada. It also recognized the impact of actions that suppressed Aboriginal language, culture, and spiritual practices, which resulted in the erosion of the political, economic, and social systems of Aboriginal Peoples. It acknowledged the role that the Government of

Canada played in the development and administration of residential schools and stated that we need to work together on a healing strategy to preserve and enhances the collective identities of Aboriginal communities. This statement is important because offering an apology and acknowledgement of the wrongs of the past is an important first step to building the foundation for a new relationship with Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples, one founded on trust and respect (Department of Justice, 2005).

The Canadian Medical Association has called on its members to show “openness and respect for traditional medicine and traditional healing practices, such as sweat lodges and healing circles” (RCAP, 1996a). This is in line with the RCAP, which promoted “openness and respect for traditional medicine and traditional healing practices” (RCAP, 1996b).

The Canadian Association of Social Workers (2004) stated that the institutions responsible for providing mental health services to Aboriginal Peoples are embedded in westernized models. They argue that these models do not correspond with the realities of First Peoples and call upon Canadian schools of social work to support the development of culturally appropriate social work education and models of practice.

Recent government initiatives

The Government of Canada has made a five-year commitment of $125 million in order to sustain critical work of healing the legacy of abuse suffered in Canada’s Indian residential school system. Although this is cause for hope and celebration, this funding will only sustain current programming for up to three years and does not allow for funding any new projects. This greatly appreciated financial gift barely touches the tip of the iceberg. The Aboriginal Healing Foundation projected that it will take $600 million, over the next 30 years, to fully address the effects of abuse resulting from the residential school system (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2005).

Aboriginal research

Aboriginal research is comprised of research committees, a research ethics board (REB), and a code of research ethics. James Bay Cree Health and Social Services Commission and the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs have research committees that review proposals to ensure that they are acceptable to their member communities. All funding agencies in Canada require approval from an REB before they will grant funds for research. For research involving First Nations, an REB has to consult with a First Nations expert or with people from the First Nations communities concerned. This is important because the REB and First Nations may have different ideas about what constitutes harm, benefits, and confidentiality (First Nations Centre, 2003a).

The development of ethical guidelines is critical to prevent further exploitation of Aboriginal communities and to protect their knowledge. First Nations Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization provided extensive information and tool kits about understanding research, ethics in health research, privacy, and OCAP: ownership, control, access and possession. The OCAP principles can be applied to all research initiatives involving First Nations (First Nations Centre, 2007). Codes of ethics developed by First Peoples’ communities are also very clear about issues of community rights.

Community rights

It is of the utmost importance that the community being researched also benefits from the research and its findings. Community consent must be obtained from representatives of the people concerned (such as a Band Council or a regional First Nations organization). Oral consent and gift giving are traditional and acceptable for First Peoples. Community control over the research process and how the results are used are very important to First Peoples. There is often an agreement on the sharing of results; the originating community has the right to know the research results. At a minimum, this means that research results should be returned to the community or the participants in a format that they can understand, such as plain-language flyers, radio broadcasts, or public presentations. Ideally, the people involved in the research should be the first to see the results. Community ownership refers to the shared ownership of information collected from a community. The information should remain collectively owned by the community from which it was taken (First Nations Centre, 2007). This is critical in developing strong relationships and rebuilding trust.

Mainstream research organizations consider it good practice, but not mandatory, to involve communities in interpreting research results, whereas, the codes of ethics developed by some First Nations communities state explicitly that if outside researchers are involved, the research results must be jointly interpreted by the community and outside researchers, governments, and universities. In the case of a disagreement over the interpretation of the results, the researcher can go ahead and publish but the community has the right to include a description of why they disagree and how they interpret the findings. The idea is that the public will be able to read both interpretations and decide which one they agree with (First Nations Centre, 2003b).

After reviewing the research regarding the effectiveness of healing and discussing current legislative and government initiatives concerning research involving First Peoples, brief and non-exhaustive recommendations are made in the aspiration of increasing awareness on issues regarding First Peoples’ culture, traditions, values, and best healing practices.

Recommendations: Government

Provide funds to allow for the development of traditional healing awareness, healing programs, and further research in best healing practices.

Continue to fund healing programs and services such as the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, created April 1, 1998, to assist First Peoples communities as they work to heal the legacy of the physical and sexual abuse of the residential school system, including intergenerational impacts. The Foundation provides funding and supports holistic and community-based healing initiatives and projects that incorporate traditional healing methods and other culturally appropriate approaches (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, n.d.).

Provide incentives for other funding organizations to commit a certain percentage of funding to promote research on Aboriginal issues.

Increase awareness with government-initiated awareness campaigns regarding the demographics of Aboriginal Peoples, the disruptive impact of colonization, and governmental obligations and policies regarding health (Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada, 2000).

Recommendations: Professional Associations and Organizations

Set aside time at annual conferences to provide professional education regarding the legacy of residential school and its impacts on First Peoples today.

Hold periodic regional and national sharing and networking conferences across associations and organizations. There is a need for information sharing and the development of relationships among healers and Elders, in conjunction with Western-trained health professionals. For example, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC), has an Aboriginal Health Issues Committee which is a multidisciplinary committee with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal members, with representation from several Aboriginal organizations and backgrounds including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis (SOGC, 2000).

Offer training to health care providers in culturally appropriate practices and interventions for First Peoples.

Encourage employees to increase their own self-awareness regarding their own stereotypes and biases that may affect treatment.

Develop specific best practice principles and guidelines to assist in working with First Peoples clients. This should be done in collaboration with First Peoples.

Provide culturally sound interventions when working with First Peoples and their children that incorporate Legacy education, cultural identity, and opportunities for healing.

Recommendations: Academic Institutions

Educate social work and other health care professional students with regards to the legacy of residential schools and the ongoing effects of colonialization on Aboriginal Peoples today.

Provide social work and other health care professional students with a critical appreciation of the centrality of Aboriginal culture in the healing process and an understanding of the diversity of First Peoples’ expression of culture. The ways in which this diversity affects one’s sense of identity and approaches to social work practice should be incorporated into the curriculum (Thomas & Bellefeuille, 2006, p. 11).

Mandate courses in cultural competency in Canadian schools of social work. For example, Wilfred Laurier University offers courses on different paradigms (Aboriginal and Western models), as well as compulsory courses on multicultural counselling or cultural competency. Wilfred Laurier University offers a one year Masters of Social Work program in the Aboriginal field of study (Wilfred Laurier University, 2007). In this program, students are taught: holistic healing practices from Elders; Indigenous identity, knowledge, and theory; and Indigenous research methodologies. There is also a cultural camp, which includes a five-day program in a camp setting in the presence of Elders, where participants learn about traditional songs, dances, teachings, and values.

Encourage and support further research in collaboration with First Peoples, for First Peoples, utilizing a combination of Western and First Peoples’ methodologies.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

The original version of this article was published in: Quinn, A. (2007). Reflections on intergenerational trauma: Healing as a critical intervention. First People Child & Family Review, 3(1), 78-82.

-

[2]

Throughout this article, the terms Aboriginal Peoples and/or First Peoples is used to collectively encompass First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in Canada. The term Indigenous is used when discussing First Peoples internationally. Other terms, such as Native, Indian, Status Indian, and non-status Indian are used in order to maintain the original language of the specific literature that is referenced.

-

[3]

The earliest documentation of people being forced to send their children to residential school is from the year 1894.

Bibliography

- Aboriginal Healing and Wellness Strategy. (2002). Draft guidelines for traditional healing programs. Author.

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (n.d.). Mission, vision, values: Aboriginal Healing Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.ahf.ca/about-us/mission

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2003). Third interim evaluation report of Aboriginal Healing Foundation: Program activity. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2005). Federal government commits $125 million to Aboriginal Healing Foundation in today’s residential school compensation package announcement. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2006). The Aboriginal Healing Foundation releases three-volume final report. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2007). Best healing practices. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Archibald, L. (2006). Decolonization and healing: Indigenous experiences in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and Greenland. Ottawa, ON: the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.: Ottawa.

- Barton, S., Thommasen, H., Tallio, B., Zhang, W., & Michalos, A. (2005). Health and quality of life of Aboriginal residential school survivors, Bella Coola Valley. Social Indicators Research, 73(2), 295-312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-6169-5

- Battiste, M., & Youngblood Henderson, J. (2000). Protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: A global challenge. Saskatoon, SK: Purich Publishing Ltd.

- Bennett, M., & Blackstock, C. (2002). A literature review and annotated bibliography focusing on aspects of Aboriginal child welfare in Canada. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada.

- Blackstock, C. (2003). First Nations child and family services restoring peace and harmony in First Nations communities. In K. Kufeldt & B. McKenzie (Eds.), Child welfare: Connecting research, policy, and practice (pp. 331-342). Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Blackstock, C., & Bennett, M. (2003). National children’s alliance policy paper on Aboriginal children. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada.

- Blackstock, C., & Trocmé, N. (2005). Community-based child welfare for Aboriginal children: Supporting resilience through structural change. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 24(1), pp. 12-33.

- Brave Heart-Jordan, M. Y. H. (1995). The return to the Sacred path: Healing from historical trauma and historical unresolved grief among the Lakota (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Five Colleges Libraries Catalog. (002001281).

- Brave Heart, M. Y. H. (2003). The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(1), pp. 7-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988

- Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2004). The social work profession and the Aboriginal Peoples: CASW presentation to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. The Social Worker, 62(4), 158.

- Carlson, R., & Shield, B. (Eds.). (1990). Healers on Healing. London, UK: Rider.

- Chandler, M. J. (2000). Surviving the time: The persistence of identity in this culture and that. Culture & Psychology, 6(2), 209-231. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1354067X0062009

- Chandler, M. J., & Lalonde, C. (1998). Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Colorado, P. (1988). Bridging Native and Western science. Convergence, 21(2-3), 49-69.

- Culley, S. (1991). Integrative counselling skills in action. London, UK, Sage.

- Davis-Berman, J., & Berman, D. S. (1989). The wilderness therapy program: An empirical study of its effects with adolescents in an outpatient setting. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 19(4), pp. 45-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00946092

- Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. (2003). Backgrounder: The residential school system. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Department of Justice. (2005). Healing the past: Addressing the legacy of physical and sexual abuse in Indian residential schools. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Duran E., & Duran, B. (2000). Applied postcolonial clinical & research strategies. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 86-100). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Duran, E., Duran, B., Yellow Horse Brave Heart, M., & Yellow Horse-Davis, S.(1998). Healing the American Indian soul wound. In Y. Danieli (Ed.), International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma (pp. 341-354). New York City, NY: Plenum Press.

- Farris-Manning, C., & Zandstra, M. (2003). Children in care in Canada: A summary of current issues and trends with recommendations for future research. Ottawa, ON: Child Welfare League of Canada.

- First Nations Centre (2003a). Research tool kit: Understanding research. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Centre, the National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- First Nations Centre (2003b). Ethics tool kit: Ethics in health research. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Centre, the National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- First Nations Centre (2007). OCAP: Ownership, control, access and possession. Sanctioned by the First Nations Information Governance Committee, Assembly of First Nations. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Centre, the National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- Fuchs, M., & Bashshur, R. (1975). Use of traditional Indian medicine among urban Native Americans. Medical Care, 13(11), pp. 915-927.

- Gagne, M. (1998). The role of dependency and colonialism in generating trauma in First Nations citizens. In Y. Danieli (Ed.), International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma (pp. 355-372). New York City, NY: Plenum Press.

- Gendlin, E. T. (1996). Focusing-oriented psychotherapy: A manual of the experiential method. New York City, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Grant, A. (1996). No end of grief: Indian residential schools in Canada. Winnipeg, MA: Pemmican.

- Graveline, F. J. (1998). Circle works: Transforming eurocentric consciousness. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Press.

- Heilbron, C. L., & Guttman, M. A. J. (2000). Traditional healing methods with First Nations women in group counselling. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 34(1), pp. 3-13.

- Hepworth, H. P. (1980). Foster care and adoption in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Council on Social Development.

- Herrick, J. W., & Snow, D. R. (1995). Iroquois medical botany. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Hudson, P., & McKenzie, B. (1981). Child welfare and Native people: The extension of colonialism. The Social Worker, 49(2), pp. 63-88.

- Ing, R. (1991). The effects of residential schools on Native child-rearing practices. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 18, 65-118.

- Keeshig-Tobis, L., & McLaren, D. (1987). For as long as the rivers flow. This Magazine, 21(3), pp. 21-26.

- Kline, M. (1992). Child welfare law, “best interests of the child” ideology, and First Nations. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 30, 375-425.

- Lane, P., Bopp, M., Bopp, J., & Norris, J. (2002). Mapping the healing journey. Ottawa, ON: Solicitor General of Canada, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Latimer, J., & Casey, L. (2004). A one-day snapshot of Aboriginal youth in custody across Canada: Phase II. Ottawa, ON: Department of Justice, Public Works, and Government Services of Canada.

- Lee, B. (1992). Colonialization and community: Implications for First Nations development. Community Development Journal, 27(3), pp. 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.cdj.a038608

- Locust, C. (2000). Split feathers: Adult American Indians who were placed in non-Indian families as children. Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies Journal, 44(3), 11-16.

- Manson, S. M. (1996). The wounded spirit: A cultural formulation of post-traumatic stress disorder. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 20(4), 489-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117089

- Manson, S. M. (1997). Ethnographic methods, cultural context, and mental illness: Bridging different ways of knowing and experience. Ethos, 25(2), 249-258. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1997.25.2.249

- Manson, S. M. (2000). Mental health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives: Need, use, and effective barriers to effective care. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 45(7), 617-627. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F070674370004500703

- Martin Hill, D. (2003). Traditional medicine in contemporary contexts: Protecting and respecting Indigenous knowledge and medicine. Ottawa, ON: National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- McCormick, R. M. (1997). First Nation counsellor training: Strengthening the circle. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 16(2), 91-99. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-1997-0008

- McKenzie, B. (2002). Block funding child maintenance in First Nations child and family services: A policy review (Report prepared for the Kahnawake Shakotiia’takehnhas Community Services). Winnipeg, MB.

- McGovern, C. (1998). More healing or less welfare. Alberta Report/Newsmagazine, 25(12), 18-20.

- Milloy, J. S. (1999). A National Crime: The Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press.

- Morrissette, V., McKenzie, B., & Morrissette, L. (1993). Towards an Aboriginal model of social work practice: Cultural knowledge and traditional practices. Canadian Social Work Review, 10(1), pp. 91-108.

- O’Neil, J. D. (1993). The path to healing: Report of the National Round Table on Aboriginal Health and Social Issues. Ottawa, ON: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

- Patterson, E. P. (1972). The Canadian Indian: A history since 1500. Toronto, ON: Collier MacMillan.

- Peters, E. (1996). Aboriginal people in urban areas. In D. Long & O. Dickason (Eds.), Visions of the heart: Canadian Aboriginal issues (pp. 305-333). Toronto, ON: Harcourt Brace & Company.

- Philp, M. (2002, September 3). The land of lost children. The Globe and Mail.

- Red Horse, J. G. (1980). Family structure and value orientation in American Indians. Social Casework, 61(8), 462-467. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F104438948006100803

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996a). Appendix 3A: Traditional health and healing. In Volume 3: Gathering Strength (pp 325-340). Ottawa, ON: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada.

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996b). Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa, ON: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada.

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC). (2000). A guide for health professionals working with Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Solicitor General of Canada. (1998). In P. Lane, M. Bopp, J. Bopp, & J. Norris (Eds.) (2002), Mapping the healing journey (p. 76). Ottawa, ON: Solicitor General of Canada, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Statistics Canada. (1996). Growing up in Canada: National longitudinal survey of children and youth. Ottawa, ON: Author.

- Sue, D. W. (1981). Counselling the culturally different: Theory and practice. Toronto, ON: John Wiley & Sons.

- Thomas, W., & Bellefeuille, G. (2006). An evidence-based formative evaluation of a cross-cultural Aboriginal program in Canada. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 5(3), 202-215. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.5.3.202

- Trocmé, N., Knoke, D, & Blackstock, C. (2004). Pathways to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in Canada’s child welfare system. Social Service Review, 78(4), 577-600. https://doi.org/10.1086/424545

- Trocmé, N., MacLaurin, B., Fallon, B., Daciuk, D., Billingsley, D., Tourigny, . . . & McKenzie, B. (2001). Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect: Final report. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada.

- United Nations. (2003). Committee on the Rights of the Child holds a day of discussion on the rights of Indigenous children. Geneva: Author.

- Waldram, J. (1990). The persistence of traditional medicine in urban areas: The case of Canada’s Indians. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Review, 4(1), pp. 9-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.5820/aian.0401.1990.9

- Warry, W. (1998). Unfinished dreams: Community healing and the reality of self-government. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Wilfred Laurier University. (2007). Aboriginal field of study. Retrieved from https://www.wlu.ca/programs/social-work/graduate/social-work-msw/indigenous-field-of-study/index.html

List of tables

Table 1