Article body

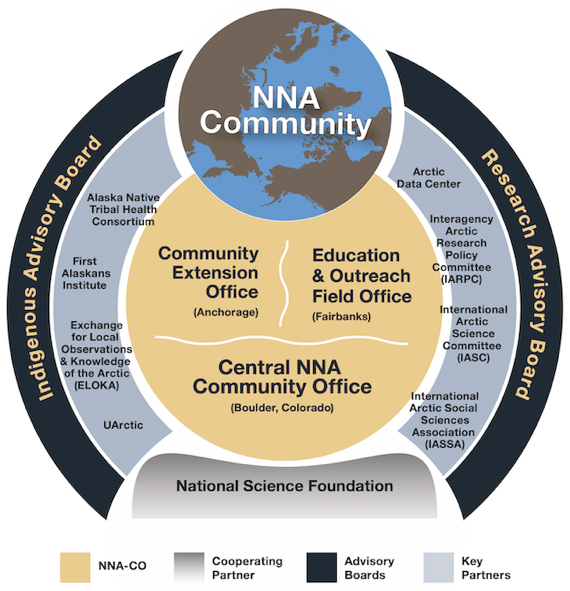

The Navigating the New Arctic Community Office (NNA-CO) builds awareness, partnerships, opportunities and resources for collaboration and equitable knowledge to generate and use knowledge within, between and beyond the research projects funded by the National Science Foundation’s NNA Initiative. The office builds capacity in early career researchers. It provides unique opportunities to inspire and engage a wide audience toward a more holistic understanding of the Arctic — its natural environment, its built environment, and diverse cultures and communities.

In Fall 2021, team members Karli Tyance Hassell (Anishinaabe), James Temte (Northern Cheyenne), Matthew Druckenmiller, Jenna Vater, Alaska Native artists Joseph (Iñupiaq) and Martha (Unangax̂) Senungetuk, and graphic designer Sebastian Garber (Athabascan) came together to discuss a vision for the NNA-CO logo design and significance. The result was a seal design that Joseph Senungetuk first sketched from ancestral memory of an ancient Iñupiaq artwork. “The Story of the Seal Design” provides additional information about the artists, the process of developing the logo and the meaning behind the caption UUMMATIÑ IÑUURUQ (“Your heart is alive”). The team not only focused on the design and its significance, but also discussed the broader impact of climate change, the history of research, Indigenous protocols and values, and working together toward leaving a positive legacy in Arctic spaces. In this video, Joseph and Martha reflect on the seal design and what it means for the Arctic[5].

Roxanne Blanchard-Gagné (RBG): Thank you both for meeting with me today! Let's start by going around the table and introducing yourselves.

James Temte (JT): Yeah, I'll go [first]! I'm James Temte. I'm an Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC)[6] and Alaska Pacific University (APU) employee[7]. I do a lot of project management, and I help run the Office of Research and Community Engagement at Alaska Pacific University. APU is in Anchorage (Alaska, USA) on Dena'ina land. We are a tribally controlled university (TCU) and an Alaska Native-serving institution, so our Board of Directors is 84% Alaska Native/American Indian. We also have an Elder's Council, so much of the work we do and the direction in which APU is headed is to support Alaska Natives and Indigenous Peoples in education and research. It's fun to be a part of that, and I'm excited for what is upcoming, and this year, we have our most significant enrollment at APU in the past decade, so we're kind of … we're growing, so it's exciting!

Karli Tyance Hassell (KTH): I didn't know that [about enrollment]! That's awesome to hear [laughs]. Boozhoo, aaniin! Karli Tyance Hassell nindizhinikaaz. Miigizi nindoodem. Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek nindoonjibaa[8]. So I greeted you in the Anishinaabe language[9]. My name is Karli Tyance Hassell; my family is from Gull Bay First Nation, which is back in Northwestern Ontario, and [located on the shore of] Lake Nipigon. I mainly grew up in Thunder Bay, Ontario. We are from the Eagle Clan, and I'm of mixed ancestry. My mother's side is of English, Irish and Ukrainian descent. I currently serve as the Indigenous Engagement Coordinator for the Navigating the New Arctic Community [extension] Office (NNA-CO) at Alaska Pacific University.

JT: Yeah, I may add to … I forgot my introduction! I'm a member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe from Eastern Montana (USA), and that's my mom's side. On my dad's side, I am Norwegian and English.

RBG: Would you mind providing some details regarding your organization, what you are passionate about in your position, and maybe how you ended up working there? Like was it your ultimate goal, or is it just part of a journey at this point in your life?

KTH: Yeah, I can go first … So I have a background mostly in environmental science and fisheries science, and my journey here at APU started as a student. I moved up to Alaska in 2017 to get my master's in environmental science. I graduated in 2019 and just kind of stuck around at APU in different capacities. But I would say since I was a small child, a lot of my fondest memories are, you know, being outside with my family, whether it was like camping or hiking or fishing; so, the lands and the waters, they've always been really important to me as Anishinaabe and as an Indigenous person, in general. I just feel a great responsibility and relational accountability to Indigenous people, and so a lot of my previous positions, including the one that I currently serve in right now, they have granted me the privilege of serving Indigenous Peoples, mostly in regard to research and science and education centred around the environment, which are all connected. However, it's sometimes difficult to navigate. I enjoy working across different knowledge systems or with different teams of researchers and scientists or academics and Indigenous communities, whether it's community members or youth or Elders, and bringing everyone together for different collaborations and partnerships. Yeah, so I get to do a little bit of that right now in my current position, which has been great.

JT: Yeah, so I would say a lot similar to Karli [Tyance Hassell]. Growing up, I spent a lot of time outside and loved hiking in Wyoming. And so we had some mountains nearby and got to go fishing and just be outside; so that led me to get my bachelor's degree in biology and then I began working for a local tribe, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe (Colorado, USA). While I was there, it was just cool to see all the work they were doing, how they would constantly go above and beyond, you know, the requirements that the federal government had or the states had, as far as controlling and monitoring water pollution, air pollution, and just really trying to restore the land; so I love that. I was able to help them and work with the team to draft the Clean Air Act for the reservation, and it was one of the first ones in the “Lower 48”[10] that the tribe put together. And so that kind of really got me thinking about tribal sovereignty and how tribes, you know, we really can. We often have better insight into what's happening on our lands and nearby; it's just out our back door or backyard. So really, that helps me kind of well; it sparked a passion for uplifting tribal voices and tribal priorities. So, I think that's one thing I'm fortunate to do now. One thing I love about this job is looking to include communities in any type of work, whether it's environmental research or social science research, but really listening to them, because they're the ones who know what the issues are in their communities around their lands, and so just being able to amplify those voices. I think it is so fun and it's really rewarding.

The other thing that I am really passionate about is, you know, kind of changing the narrative. I think for so long Western research has identified problems, and it has identified like these, you know, these areas are… They are really lacking or they are not working well; but I think that we can change the narrative to so much that communities do. They are thriving in certain areas, so let's research more like that. Let's start there and develop all the assets we have instead of just focusing on the issues or the problems. So I love that kind of narrative shift.

RBG: Speaking about the narrative shift, can you give me some examples of your day-to-day activities for which you are trying to advocate?

JT: Yeah, so before I came over to Alaska Pacific University, I worked with the National Tribal Water Centre (NTWC).[11] And one of the problems that a lot of the agencies identified with, you know, there's a lot of staff turnover at water treatment plants. People don't pay their bills, and there's just no interest in it; and so it was like the water and sewer infrastructure was failing a lot of times, and so … What I thought is like as Indigenous people, we value the water. Water is sacred, so let's begin there. Let's start with our values. Let's start with why it's important to us, and then carry it over into the water treatment plant and celebrate it. And so we would do these meetings. I called them “Visioning Meetings," where we would talk about the water culture in the community and why it's important; what it was used for. And then we invited artists [to join the conversation]. We painted these big, beautiful murals on the water storage tanks to celebrate the community and their values. We saw that through that process of just talking about it and also celebrating it, more people would pay their water bills, staff would retain their jobs longer. So, we've seen water treatment systems go from operating with a negative balance, money balance to thriving [operating in a positive balance]. So, it's been really neat. If you focus on a lot of the values in the strength to see positive change and a lot of times it's just, you know, people need to be a little bit more intentional. I think research can be intentional in those areas.

RBG: That's very inspiring! Since 2018, I have been privileged to live on and off in Cambridge Bay, Northern Canada. I witnessed a narrative shift regarding certain areas and how research and development are thriving toward celebrating community empowerment and the values of Iqaluktuuttiarmiutat. I think that the community, and researchers working with the community members and institutions, would gain a lot from extending their connections to your Arctic network for knowledge sharing as a community of practice. I am guessing that is what you are doing with your podcast: Arctic Podcast Together.

JT: Yeah! Karli, do you want to talk a little bit about the podcast?

RBG: If you do not want to talk right away about the podcast, you may want to discuss more about how your various projects contribute to growing convergence research across Alaska.

KTH: Yeah, several NNA-CO funded projects, in general, really focus on topics or research driven by specific challenges across the Arctic in a very multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary way and focus or viewpoint. For example, engineers are working with social scientists focusing on water sanitation infrastructure. They are also gathering qualitative data on user needs, on human health. So really, they are interweaving or integrating knowledge systems and various tools to co-develop research. in response to what communities face, for example. So, the community office is developing convergence working groups composed of members from various backgrounds, expertise, career fields or even levels, as well as early career professionals or students, or maybe more “experienced” scientists and researchers. They come together and develop a set of activities related to specific themes of health and well-being in community adaptation and resilience planning or even international collaboration, for example. So, a little bit more [about convergence working groups] can be found on our website. Still, we're in the process where we're first starting to establish those working groups and think about themes. I think these working groups can go back to the lessons learned about specific projects, because these groups could share and also contribute to changing policy – changing how research is conducted or just different things like that. So, I think the community office is centring lessons learned, building capacity, and increasing education related to those themes and overarching objectives.

JT: I think something else that just in the past year we noticed are these emerging best practices. So I think [that with] some of the projects that were set up at the beginning of the Navigating the New Arctic Program, we've learned so much. There are really emerging best practices as far as equity, setting up steering committees and compensating them for their time or setting up local research liaisons in communities and compensating them… Also: looking at different power dynamics. If you are a researcher, ask yourself “What does it mean to partner with the community?” and, so truly, encourage institutions to have principal investigators living in the community and from the community, and not just, you know, at an academic institution. It's really looking to balance and celebrate that equity. It's been really neat to see these kinds of things, and then be able to support and amplify these best practices.

RBG: How do you select stakeholders from the community that do not have a Western-based scientific background?

JT: One of the cool parts about the Navigating the New Arctic Program are projects that centre co-production of knowledge; it's really braiding Western science with local and Indigenous knowledge. Folks in the community, they have such a strong sense and local Indigenous knowledge. So a lot of the time, they might not have the Ph.D. and Physics [certifications], you know, but they do hold very valuable information. It's really honouring the knowledge that they have and then braiding it with the Western science [knowledge].

RBG: … So it is a personal and volunteer decision on their part, and people are coming to you; you don’t need necessarily to go pick the people with whom you collaborate.

JT: Yeah, so that's a really good way [to fill positions]. A lot of times, in some projects I've worked on, you just put out [the advertising and wait and see] if anybody is interested in your topics of interest. Then you can build the team around the community’s interests.

RBG: That’s so great! I know that you previously said that you don’t know a lot about the NSF’s 10 big ideas[12], but would you like to talk about it and how NNA-CO fulfills part of its mission by building awareness and addressing challenges in the rapidly changing Arctic?

JT: I think the National Science Foundation (NSF) came up with these 10 Big Ideas. And really what the purpose of the ideas is to set long-term goals and research agendas. So navigating the new Arctic was one of those. I think that initially they have like five years of funding. And they said we're going to look at this program for five years and hopefully they carry it on for another five. It's a research trajectory focus of the National Science Foundation.

KTH: I think the NNA program in general is really focused on holistic thinking, on connecting knowledge and research about social systems, the natural environment and the built environment [in terms of infrastructure] – that is the scope in mind; and addressing or building awareness of changing the Arctic is the priority. I think a lot of our work, especially here at APU, at the extension office (NNA-CO), we really understand and know that Arctic Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately affected by climate change. We also have thousands of years of knowledge about the lands and the water. We need to be a part of those forward-thinking solutions on a local scale, regional scale, and even a global scale. There has been profound impact to communities across Alaska.

I don't know if you've seen the news recently, but western Alaska [this past weekend] is facing really devastating impact related to an extreme weather event, a storm[13]. There's also melting sea ice and permafrost that really impact access to traditional foods or practising lifeways. These all impact health and well-being, food security, and community health, which is related to human mental health, for example - everything is connected, right? At the Community Extension Office (NNA-CO), a lot of our work really centres around Indigenous research frameworks, supporting relationship building, which is what James [Temte] had mentioned, and really centring community needs and priorities. A lot of that is done through education and outreach, and we have a team centred around education and outreach who are working with teachers, for example, across Alaska. There are some scientists and teams who are developing curriculum and they're bringing that to classrooms. A lot of our work is highlighting those best practices through sharing stories or gathering resources, and spreading the word about all this really great information that is out there… and connecting people and ideas - I think that's a big part of what the office does.

RBG: From your perspective, what is a common misconception about working with Arctic-based communities? Or working within an Arctic research station?

KTH: I would say that a lot of researchers from the “Lower 48” - which is what we call the contiguous US - they might come up to Alaska or to Arctic communities for the first time with a specific agenda or timeline in mind, especially when it comes to land or grant-related funding. So they may not have worked previously in the area or with a tribe before, and don't really understand the intricacies of establishing connections or community trust.

All of which really takes time, especially in the light of historical or ongoing helicopter researchers or scientists that kind of come in and out of communities with an extractive mindset. They don't understand that it's really important to compensate people for their time and input into research projects, or better yet, really establish that partnership and centre community concerns in developing or co-developing research questions and solutions. I think that's definitely something that we see a lot. But it's changing, you know; people are really recognizing [the harm in] that. You can't have a research project in Alaska, especially in a specific region, without centring community knowledge - that's super important.

JT: … And there's a lot of missed opportunities and some research to really uplift communities and support their different desires. For instance, there is a huge movement on [revitalizing] Indigenous language and using Indigenous language. There's no reason why research projects can’t pay a translator to produce education or outreach material in local languages. I think there are just little things that if you just go the extra step, a community will really see that. While you're supporting them, even though it might be a research question that you have, you're supporting the preservation of language as well. Looking for little nuggets of stuff and what the community is really interested in and how you can tie your project to that… I think it's fun and it's exciting, and it’s a great way to support communities through your research.

RBG: It has been voiced briefly how missed opportunities from researchers cannot lead communities to benefit from their work. You have already given some examples, but can you tell me more about how Indigenous communities benefit from your work at the NNA Community Office? And how do you amplify Indigenous voices?

JT: I think a lot of the work that I like to see really is supporting communities and researchers. Supporting researchers and just giving them more tools to do the work in a good way [is important]. We're developing resources and developing our website with more and more tools. Hopefully, by the time this project [the NNA-CO] is over, there's like a whole toolkit for a good way to do research. And this is a way you can support the community. Then for the communities, it is like, if you're interested in research or you're interested in learning more about these specific areas, how can we connect you and support you in learning about these, and participating [or leading] the research. I like to think of it sometimes as baseball; whatever is a nice underhand pitch[14]. We can help throw the underhand pitch so that communities and the researchers can just knock it out of the park. Trying to set people up for success is one thing with which I hope we can really help.

KTH: Yeah, I think several of our activities, like the Broader Impacts Network[15] really bring people together and start or sustain those conversations. I think communities can learn a lot from each other. For example, if a community is working on a specific project, there might be another community in the region or maybe elsewhere in different countries that could really learn from each other - this is supporting commuty knowledge exchange. We aim to uplift Indigenous self-determination and community autonomy, which is really the basis of sustainable decision-making and stewardship of the Arctic. I think that a lot of our work, [with] such as the podcast, for example, we really hope to inspire and engage, like, a wide audience to share best practices or success through story. With grant-funded research, it's often difficult to explain the true impact that a project has had; for instance, if a research project has youth involvement, and they get to go out in the field and learn about different methods for gathering data in the environment. If researchers get to visit a school and talk to youth, that could really inspire someone to [stay in] school and get an education, but also encourage them to bring their whole self, their traditional knowledge, and their language. The goal would be to bring that back to the community and focus on different solutions from within the community. I think it's like a trickle, a domino, or a snowball effect. I think [that] collectively, a lot of these projects have an impact just in different ways, and I think our office really hopes to kind of amplify that and share that and hope to inspire others or other research or other projects to do those types of activities, and really have that impact in different ways. There is already a lot of work being done, and a lot of work left to do. I hope that we can bring people together to lead and support the work in different capacities.

RBG: You mentioned [that] the Arctic Together Podcast could contribute to starting a conversation on sustainable decision-making and stewardship; please tell me more about it and if you have any favourite segment!

KTH: Yeah, so [as of September 19, 2022], we've only really released the first episode [Parts I and II][16], but it is aimed to be a quarterly podcast series, with special events or live coverage of different activities, meetings or conferences our office might host. We really hope to share stories about the NNA community and beyond. Our guests really have a way of sharing story through storytelling, and we invite them to share lessons learned. Whether it's through science communication or featuring resources for collaboration, we also aim to focus on different parts of the Arctic and different Arctic Nations. So this first episode is focused on Alaska, and the next episode is going to be partly focused on Canada. I think one of my favourite segments of the podcast is the Intersection segment, where we host or feature different Arctic artists or musicians[17], and I think that part is fun. It's a fun conversation with the art/music community - including the impact of art on self and community. It's always fun to hear about what everyone is doing across different regions, including the different ways to get people involved, and to get excited about sharing research through a new medium. There's also a really awesome resource guide and show notes that get published alongside each episode, with additional readings, information about the guests or about the specific topics that we talked about in each episode. So it's work, but it's fun work! It is a lot of fun to talk to people and get involved in the production of everything. It's been great, and I'm excited to share more episodes in the future.

JT: When Karli and I were talking about the podcast, we were thinking: “Who's the primary audience?” We were also thinking about reaching researchers who do not live in Alaska and are from different parts of the United States or the world. The podcast is a way to introduce them to Alaska Native culture or different Arctic cultures, and really uplift Indigenous voices. I think it's really neat to hear through the conversations what people are excited about, and the more researchers [who] hear what people are excited about… then maybe they could try to incorporate something from that into their projects. I think that would be really cool.

KTH: I think podcasting is a more informal way to share research stories. There's a lot of conversation, back and forth, and a lot of laughter, which is great. I think [that] what we hope to do in the future is get youth and Elders involved to encourage generational dialogue. Gathering and sharing stories from youth, from different perspectives or voices…I think it's going to be really exciting!

RBG: … So how many people are on the team of the Arctic Together Podcast? Is it only the two of you who came up with the idea and started it?

JT: Basically, we're looking at ways [with which] we can reach the scientific community that may be through this kind of informal [way], but really kind of help introduce folks to communities up here, community members, community priorities, community voices, in hopes to better equip them for when they do travel up here and meet with folks. [To] just kind of give them a little bit more information, a few more tools in their toolboxes, to help to manage expectations, and then really help them to see and understand the value of including communities in the research.

KTH: James and I are the co-hosts of the podcast, and we now have someone in post-production. It's been interesting to see how far this podcast … how it has reached different people. Through different online social analysis or metrics tracking, we've been able to reach over 298[18] people in many countries - not even in North America, but in Europe and in Australia… just different parts of the world. We were, like: “Wow! I had no idea that this was going to be listened to in other parts of the world.” It's been really cool to see who's been listening, and yeah, if anyone has any feedback or ideas for the podcast, we definitely welcome folks to get in touch with us.

RBG: Actually, I got an email from a group called Rising Voices[19] in the United States, and that organization was inviting the addressees to listen to your podcast. While streaming it, I was like: “Oh my gosh, that's so great! I need to talk to those people and get to know more about their amazing projects and what else they are working on.” In this regard, you’ve already described some of your work; but I was wondering, as the Arctic is well-known to pose communications challenges and many of your projects include the use of technologies: What are the biggest challenges you faced towards connectivity infrastructure and technological innovations regarding the co-production of knowledge processes or related to engaging a broad audience with action-oriented research?

KTH: I think we often fall into the trap of being siloed across disciplines or across teams and institutions. A lot of the time, people just don't know who's doing what, and it's really difficult to navigate across hundreds of research teams or institutions, or different funding opportunities too… and then know the associated deliverables or goals of specific projects and then really communicate that and translate that well, especially across different scales. So, that's really related to the connectivity of people. We try to encourage folks to think about different methods of communication. And people often don't realize that a specific community might have only a set amount of [Internet] data [access] that they're all sharing, for example; so you can't even download an attachment from an email if you send specific materials about a research project. It's simply not accessible. People just aren't aware of that, and so those are just kind of “small things.” But there are most certainly other things that people need to be aware of, so we hope to generate awareness and then offer different solutions. We say: “Go on Facebook! Start a Facebook Group!” A lot of community members are on Facebook, that’s how they communicate. They have community Facebook groups, and it's a great way to advertise opportunities, communicate knowledge about different research [projects]; and, yeah, I think even just mailing things is powerful. Everyone is so caught up in emails; I think printed materials are often something that people forget about these days, but they're still really valuable forms of communication in remote areas. This is especially true when it comes to Elders or reaching folks who may not be online. A lot of folks listen to radio in communities, so that's another way to kind of advertise or to get people to listen about different opportunities or engage in knowledge dissemination.

JT: I think, for one thing, that is something our offices are working on. We can have the podcast that focuses on reaching the researchers; but as far as reaching communities, we are working on a Zine[20]. We're featuring different projects and we're sharing “portrait features” of people who are involved in the Navigating the New Arctic program. It will be printed, so we can mail it out to all of the communities across Alaska and also to the schools. It’s something that could sit in the tribal offices, and people could just look at it when they are waiting and learn about projects and research. I love thinking about different ways to meet people where they're at with communication and science communication, so that should be coming out here in the relatively short future. We're working on [it] right now.

RBG: You said that you are trying to reach other scientists with the Arctic Together Podcast, mainly the ones from the South; who else do you wish to reach out to? Maybe not science people…

JT: Yeah, I think so, and I think several researchers in Alaska, but also community members who are interested in what's going on and what is this “Navigating the New Arctic program.” So it's a good way just to reach a broad spectrum of folks.

RBG: Right! So, from your perspective, how is it to navigate through Indigenous and Western scientific approaches, and empower new research partnerships from local to international scales?

KTH: As an Indigenous person who has a background in “Western” environmental science, I try to bring these two ways of knowing together. I think a lot of the time people are talking about the same thing, but just in different languages, and it's easy to get lost in translation. I like to encourage different frameworks or approaches. I'm not sure if you're familiar with the Two-Eyed Seeing Framework called Etuaptmumk,[21] which is a framework that brings together Indigenous and Western scientific ways of knowing. Again, I think it just comes down to people and connections, and really establishing a reciprocal dialogue and investing in relationships in a sustainable way. When it comes to research partnerships, at local versus international scales, it's all about methods of communication and thinking about “Who's your target audience?”, with the realization that not everyone talks or thinks in the same way. It really highlights the value of bringing different people together from different backgrounds or from different expertise, as well as generations. [It’s a matter of] really focusing on how to get youth involved, ‘cause they're really the next generation who is going to be caring for the Arctic. I think that's how you empower people too - recognizing that everyone has a part to play and knowledge to bring forward and to share; that's really how the Two-Eyed Seeing Framework navigates or operates - it's all about process rather than outcome. It’s recognizing the value in different people or knowledge systems and highlighting that.

JT: You know, that is one thing I love - the Two-Eyed Seeing Framework. Art can be a very powerful tool to engage communities and celebrate communities in art. Art is a great way to start discussions and learn about communities’ priorities; so I've done several projects. I really like to encourage the use of art in any type of community engagement, and it's a great way to draw a crowd. Still, it's also really neat, because you leave something with the community instead of just taking from them. Hence, it's just a great way to help to develop build[ing capacities], and then you can leave something there for the people. So I think it's really a way of investing in communities. It is a great way to have discussions and learn more.

RBG: Yeah, I think we can all agree that giving back is super important and, if I may, I think is one of the principles that guide your research centre. Is there any other guiding principle that resonated most with you?

KTH: One of them is institutional change! Education systems have a lot of impact and really require awareness of belief systems. This brings attention to issues of equity and barriers to education and research. We hope to bring attention to that and recognize that transformative change has to happen in order to address those barriers and to address access to funding, for example. There are long-standing issues deeply rooted in colonialism, and we need to address those through equitable ways. I think a lot of what the community office is about is really bringing awareness of that, and how it really shapes research priorities, who gets funding or what gets funded. We're also developing a curriculum [or set of classes] for a course that's really all about Arctic-based collaboration. And so bringing different knowledge systems or different experts together and sharing best practices, sharing multiple ways of learning and knowing and focusing on or celebrating cultural differences, celebrating language… focusing on our historical challenges when it comes to research. I think James [Temte] could probably talk a little bit more about this, but the learning and unlearning that has to happen about our own biases or perspectives.

OK, yeah, we do have some work to do. How do we move forward? How do we get to where we want to be? What are the steps and how do we eliminate those barriers in education or in research that have prevented people from accessing opportunities, resources or funding and how can we address those challenges together?

JT: Yeah, I think Karli [Tyance Hassell] and I love the institutional change; it's really good! Another one of my favourites is Indigenous self-determination. I think we really need to respect that and hold it. I think in research, a lot of times folks won't research if they know they can't share what they find and think - even though it could be so powerful and valuable to the community. I think there's a need to uphold Indigenous self-determination, and uphold data sovereignty. It’s really centred around respect. I think honour and respect are just really built around Indigenous self-determination and that oftentimes, [this] hasn't been recognized in research. So, I love to think of different ways I can help communities, you know, like getting the information they need and then just respecting them [and their wishes]. If they want to share it, great; if it's just special to them or it's sacred, then we need to honour that. So, yeah, I think that would be the one that I am really focusing on. I learned this from early on when I was writing environmental codes for the Southern Ute Indian Tribe. I was like: “We can do it! Let's do it! Let's exercise self-determination.”

RBG: So, is exercising self-determination part of your next five-year plan regarding the Arctic Together Podcast and the NNA Community Office (NNA-CO)? What are your desired outcomes for the upcoming years?

JT: I'll show you a dream of mine that I have; it kind of blends institutional change and Indigenous self-determination, but it would be to have at least half the awarded grants go directly to Indigenous organizations or communities. I think that would be really super cool, if there's a way that our office can kind of help raise awareness or develop frameworks to really support that. That would be just wonderful, and so that communities identify an issue and have access to applying for funding. In regard to the institutional change, there is this whole application process that can be really tedious and a little bit scary to just enter into. So, how can we change the way applications are submitted? I think that it would just be amazing if there could be a “tribal set aside”, where half the funding goes to tribes and tribal organizations. I think that would be really cool!

RBG: What about you Karli [Tyance Hassell]?

KTH: I'm still thinking! It's hard to think about, you know, where you want to be in five years from now. Our community office (NNA-CO) team is comprised of so many wonderful people with diverse backgrounds and a lot of expertise in different fields, and I think that's something worth thinking about as a team, you know? What is the impact that we want to have on the research community in the Arctic? How do we want to sustain relationships? I think that's just a question that a lot of people have in general, when it comes to grant-funded offices or research projects. It's like, how do we make this sustainable? How do we think about the scalability of the impact that we have collectively? And, yeah, those are just really big questions that we're thinking about currently, but those are also things that we hope to incorporate throughout our five years. So as we develop these activities, this curriculum, this programming, [we’re] thinking about “How do we evaluate this?” How do we share the story of the community office and everyone else’s story who was involved in NNA? Yeah, James’ [Temte] point of Indigenous self-determination and having more funding go directly to tribes would be amazing. I think a big part of what I hope to address is championing youth and uplifting our Elders. Both groups have a lot to offer. The youth today, students at our institutions - they are the future leaders. They are the ones who are going to take care of the Arctic, and I think it's important to kind of not only involve them in a lot of work and activities throughout the next couple of years, but also hear from them and their direction. I'm sure they have a lot of really great ideas to bring to the table, but to also hear from our Elders[is key]. I would really love to be continually guided by Elders. We also have an Indigenous Advisory Board to regularly guide our office. It's really a big question: “Five years from now, what are the desired outcomes for the community office (NNA-CO)?” I am still thinking about it, but, yeah, I know that the impact that we have has the potential to create change. I think we just really hope to bring people together and maybe change that mindset, change the narrative, have that little effect in different ways with many people across many projects that really changes institutions or changes the way research is conducted [as a whole]. I think that would be really amazing!

Roxanne Blanchard-Gagné (RBG): I'm crossing my fingers that your wishes will come true within five years. Are there any other important aspects of your position or NNA Community Office's projects that we haven't covered and that you wish to address?

James Temte (JT): I think what I would say is, there's just a lot of emerging best practices. And if it wasn't in your project at the beginning, it doesn't mean it can’t be in your project right now. It's easy and I think through COVID[22], we've learned that sometimes you do have to pivot. I think including communities in those decisions when it's research that involves them is really powerful and it'll help the success of research in the Arctic. For all the folks doing research out there, it's been tough lately, so give yourself a pat on the back! You guys are trying to do your best, and if there's anything that the office can help you with, feel free to reach out.

Karli Tyance Hassell (KTH): Yeah! We also have a Twitter[23] and Facebook[24] page, where we share a lot of information pretty regularly about opportunities and dissemination regarding different research [projects] that are going on in the Arctic. Our handle is @Arctic Together, so feel free to follow us. And we look forward to sharing more about the great work that everyone is doing: researchers, communities, projects - the future is really bright and exciting!

Appendices

Acknowledgements

We honour the Indigenous Peoples across the Arctic who have been the original stewards and caretakers of the lands, waters, and plant and animal relatives since time immemorial. Special thanks go to the other NNA-CO team members for their continued dedication to improving capacity-building, sharing story, uplifting the NNA community and supporting the Arctic. The NNA-CO is supported through a cooperative agreement (Award # 2040729) with the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Biographical notes

Roxanne Blanchard-Gagné

Étudiante au doctorat à l’Université Laval, Roxanne Blanchard-Gagné a acquis au fil des années un vif intérêt pour l’anthropologie sociopolitique et l’ethnohistoire portant sur les réalités et les enjeux autochtones contemporains au Canada, particulièrement au Québec et au Nunavut. Plus précisément, son expertise est axée sur les relations humains-animaux [les chiens dans les communautés inuit, d’où son sujet de mémoire de maîtrise : Réveil de la pratique du traîneau à chiens à Iqaluktuuttiaq (Cambridge Bay, Nunavut) : perspective multiple sur les transformations des relations Inuinnait-Qinmit (2021)] et sur divers enjeux sociaux, notamment la pauvreté, l'exclusion, l'itinérance, le principe de souveraineté, l'empowerment, la santé holistique ainsi que les rapports de force entre les Premiers Peuples et les divers paliers gouvernementaux.

James Temte

Growing up in the least populated state located in the United States of America, I have always been fond of wild landscapes and the human connection to the land and places. I am a member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, and I joined Alaska Pacific University (APU) in 2018. I currently serve as the Senior Director at the Office of Research and Community Engagement (ORCE) at the Alaska Pacific University. I also serve as an adjunct faculty member at the Institute of Culture and the Environment. My favorite topics to teach in class include modern Indigenous art, climate change and the co-production of knowledge.

Throughout my career, I have spent time with tribes in all regions of the U.S. and, most recently, in Alaska. Learning of the similarities and unique differences between Indigenous peoples has been fascinating. This always reminds me to approach my work clearly and open-mindedly. My interest in the Arctic is with its people and their interactions with the natural world. I have a passion for supporting Indigenous voices, tribal sovereignty, tribal self-determination and co-production of knowledge, including Indigenous methodologies and Western science. In this process, I use innovative community engagement methods, including mural art, traditional Indigenous culture, science and media. I love to work with communities on multidisciplinary teams that inspire a broader understanding. In my view, the best part of being involved in community research is when community voices and priorities are not only heard but also supported, celebrated and preserved.

Karli Tyance Hassell

I am Anishinaabe from Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek (Gull Bay First Nation), and I have mixed Ukrainian, English, and Irish ancestry. I grew up on the north shore of Lake Superior in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. I first came to Dena’ina Ełnena in 2017 to study as a master’s student at the Fisheries, Aquatic Science and Technology Laboratory of Alaska Pacific University (APU). Upon graduation, I served as a program coordinator for the Alaska Indigenous Research Program and as the Indigenous Engagement Coordinator with the Navigating the New Arctic Community Extension Office at APU. I am now a Senior Policy Coordinator at the Central Council of Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

I have a broad background in environmental and fisheries science with over ten years of experience in Indigenous community education, outreach and land stewardship planning, including expertise in equitable engagement strategies for tribal partnerships, knowledge co-production, communications, facilitation, and community-based research and engagement. I often liaise across several ways of knowing and knowledge systems, interdisciplinary teams and sectors. I aim to strengthen relationships among Indigenous communities, Youth and Elders, academia and scientists, policymakers and managers, tribal organizations, and research collaborators. My Anishinaabe values and traditional teachings are the foundations which drive my passion for serving Indigenous communities. I am a traditional women’s jingle dress dancer, ribbon skirt maker and hand drummer, and I enjoy being out on the land and waters with my family and friends.

Notes

-

[1]

That interview took place on September 19, 2022.

-

[2]

M.A. in Indigenous Studies, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT)

B.A. in Multidisciplinary Studies, Université de Montréal

-

[3]

M.S. in Applied Environmental Science and Technology, University of Alaska Anchorage

B.S. in Biology, Fort Lewis College

* Since recently, James was appointed as Senior Director at the Office of Research and Community Engagement (ORCE) at the Alaska Pacific University.

-

[4]

M.S. in Environmental Science, Alaska Pacific University

B.S. in Environmental Science, University of Guelph

* Since recently, Karli was appointed as a Senior Policy Coordinator in the Native Lands & Resources Division for the Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska (April 2023-Present).

-

[5]

“Traditional knowledge or understanding of the relationship between the seal and the hunter is what keeps the seal alive, but it is an understanding and relationship that sustains life itself,” says Joe. “The heart is a common element among us all and we must use our heart to understand our complex shared history and recognize the role we all have in contributing to transformative or institutional changes to support shared research and community needs.” Martha goes on to say, “We care about the Land, and its people. As we navigate the changing Arctic, we look to our seal relation as a teacher who spends part of its life on the ice and in the waters. The seal reminds us to use your heart in solving complex problems together. The seal has knowledge. The Indigenous people of the Arctic have knowledge. The researchers or scientists have knowledge. Together we have a solution.” (NNA-CO n.d. : 4).

-

[6]

The ANTHC is a non-profit Indigenous health organization meant to meet the unique health needs of Alaska Native and American Indian people living in Alaska. In partnership with the Alaska Native and American Indian people that we serve and the tribal health organizations of the Alaska Tribal Health System, ANTHC provides world-class health services, which include comprehensive medical services at the Alaska Native Medical Center, wellness programs, disease research and prevention, rural provider training and rural water and sanitation systems construction (Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium 2022). For more information, visit https://www.anthc.org/.

-

[7]

James Temte is currently a Senior Environmental Health Consultant at the ANTHC and is also serving as the Acting Director of Alaska Pacific University’s Office of Research and Community Engagement.

-

[8]

Anishinaabe: Boozhoo, aaniin! Karli Tyance Hassell nindizhinikaaz. Miigizi nindoodem. Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek nindoonjibaa. English translation: Hello, greetings. Karli Tyance Hassell is my name. I am part of Eagle Clan. I come from Gull Bay First Nation.

-

[9]

Also known as Anishinaabemowin or Ojibway.

-

[10]

Strictly speaking, the term refers to the 48 contiguous United States in North America (USA), which exclude Alaska (49th state) and Hawaii (50th state).

-

[11]

The NTWC is a non-profit organization located in Alaska. For more information, visit https://tribalwater.org/.

-

[12]

In 2016, the National Science Foundation (NSF) unveiled a set of “10 Big Ideas”, such as, but not limited to:

-

Future of Work at the Human-Technology Frontier

-

Growing Convergence Research

-

Harnessing the Data Revolution

-

Mid-scale Research Infrastructure

-

Navigating the New Arctic

-

…

For more information, visit https://www.nsf.gov/about/congress/reports/nsf_big_ideas.pdf.

-

-

[13]

On Sunday, September 18th, 2022, a historical storm lashed the State of Alaska. For more information, visit https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/09/18/alaska-storm-typhoon-merbok/.

-

[14]

In baseball, it refers to a slow pitch that is easily hit.

-

[15]

The NNA Broader Impacts Network, hosted by the NNA-CO, was created to foster collaboration and learning across projects, share practices across the network, connect NNA scientists to opportunities and increase visibility of NNA research.

-

[16]

The first episode of the Arctic Together Podcast featured conversations about the co-production of knowledge and promotion of equity, the Alaska Native music and art scene, and working in relationship with community.

-

[17]

Episode 1 of the Arctic Together Podcast featured world-renowned artist Apay’uq Moore and musician Stephen Qacung Blanchett - a soloist and member “Pamyua” - a Yup'ik (Alaska Native) soul music group.

-

[18]

As of December 7th, 2022, the podcast had reached listeners in 18 different countries.

-

[19]

The Rising Voices Center for Indigenous and Earth Sciences, also known as Rising Voices, is a network of “Indigenous, tribal and community leaders, atmospheric, social, biological and ecological scientists, students, educators and experts from around the world” (Rising Voices 2022 : § 1). For more information, visit https://risingvoices.ucar.edu/.

-

[20]

The Arctic Together Zine is a bi-annual digital and print publication that will be mailed to Alaska Native tribal offices and schools to share more information about NNA research and will include creative components like colouring pages, poetry or photography.

-

[21]

“Two-eyed seeing” (Etuaptmumk, in Mi’kmaq or Miꞌkmawiꞌsimk) embraces “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all,” as envisaged by Elder Dr. Albert Marshall.” (Reid et al. 2020 : 243)

-

[22]

COVID-19 pandemic.

-

[23]

For more information, visit @ArcticTogether on Twitter.

-

[24]

For more information, visit Arctic Together Facebook Group.

Bibliography

- Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, 2022, « Overview », Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. Retrieved from https://www.anthc.org/who-we-are/overview/.

- NNA-CO — Navigating the New Arctic Community Office, n.d., The Story of the Seal Design. Navigating the New Arctic Community Office (NNA-CO). Retrieved from https://www.nna-co.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/Story-of-the-Seal-Design.pdf.

- REID, Andrea J., ECKERT, Lauren E., LANE, John-Francis, Young, Nathan, Hinch, Scott G., Darimont, Chris T., COOKE, Steven J., BAN, Natalie C. and Albert MARSHALL, 2020, « “Two-Eyed Seeing”: An Indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management », Fish Fish, 22 : 243– 261. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12516.

- Rising Voices, 2022, « About. Indigenous knowledge systems in the Earth sciences. », NCAR, Rising Voices. https://risingvoices.ucar.edu/about.