Abstracts

Abstract

Background: Goals of care (GOC) planning involves healthcare providers (HCPs) discussing patients’ health preferences, including code status options ranging from “full code” (cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR] and intubation) to “do not resuscitate (DNR)”. In 2008, Ontario introduced the Do Not Resuscitate Confirmation Form (DNR-CF), which permits first responders to withhold CPR when a valid form is present. Despite routine GOC conversations during hospital admissions, few physicians complete DNR-CFs to guide community-based emergency responders. Objective: We aimed to identify the completion rates and perceived barriers to completing DNR-CFs among general internists. Methods: We conducted an online survey of general internists at two Hamilton hospitals, followed by a focus group using a semi-structured interview guide. Results: Among 14 survey respondents, only 16.7% had completed a DNR-CF, despite all being familiar with the form. Main barriers included knowledge gaps, limited accessibility and uncertainty about responsibility. Focus group participants expressed concerns about the redundancy of completing the DNR-CFs in inpatient setting, the form’s validity overtime and medicolegal implications. Conclusion: Despite widespread familiarity with DNR-CFs, completion rates remain low due to systemic, provider-related, and ethical barriers. These findings raise ethical concerns about patient autonomy and potential for unwanted harms associated with resuscitative efforts. Strategies to address these challenges include improved provider education, clearer delineation of roles, and systemic support for GOC planning. Enhancing the completion of DNR-CFs can help ensure that patient wishes are respected, particularly in community emergencies, thereby upholding ethical standards in end-of-life care.

Keywords:

- goals of care planning,

- do not resuscitate,

- DNR,

- end-of-life care,

- confirmation forms,

- patient autonomy

Résumé

Contexte : La planification des objectifs de soins (ODS) implique que les prestataires de soins de santé discutent des préférences des patients en matière de santé, y compris des options d’état de code allant de « code complet » (réanimation cardio-pulmonaire [RCP] et intubation) à « ne pas réanimer » (NPR). En 2008, l’Ontario a introduit le formulaire de confirmation de non-réanimation (FC-NPR), qui permet aux premiers intervenants de ne pas pratiquer la RCP en présence d’un formulaire valide. Malgré les conversations de routine sur les ODS lors des admissions à l’hôpital, peu de médecins remplissent des FC-NPR pour guider les intervenants d’urgence de la communauté. Objectif : Nous avons cherché à identifier les taux d’achèvement et les obstacles perçus à l’achèvement des FC-NPR parmi les internistes généraux. Méthodes : Nous avons mené une enquête en ligne auprès d’internistes généraux de deux hôpitaux de Hamilton, suivie d’un groupe de discussion à l’aide d’un guide d’entretien semi-structuré. Résultats : Parmi les 14 répondants au sondage, seulement 16,7 % avaient rempli un FC-NPR, même s’ils connaissaient tous le formulaire. Les principaux obstacles étaient le manque de connaissances, l’accessibilité limitée et l’incertitude quant à la responsabilité. Les participants aux groupes de discussion ont exprimé des inquiétudes quant à la redondance des FC-NPR en milieu hospitalier, à la validité du formulaire en dehors des heures normales et aux implications médico-légales. Conclusion : Malgré une large connaissance des FC-NPR, les taux de remplissage restent faibles en raison d’obstacles systémiques, liés aux prestataires et d’ordre éthique. Ces résultats soulèvent des questions éthiques concernant l’autonomie des patients et les risques de préjudices indésirables associés aux mesures de réanimation. Les stratégies visant à relever ces défis comprennent une meilleure formation des prestataires, une délimitation plus claire des rôles et un soutien systémique à la planification des ODS. Améliorer le taux de remplissage des FC-NPR peut contribuer à respecter les souhaits des patients, en particulier dans les situations d’urgence communautaire, et ainsi à maintenir les normes éthiques en matière de soins de fin de vie.

Mots-clés :

- planification des objectifs de soins,

- ne pas réanimer,

- NPR,

- soins de fin de vie,

- formulaires de confirmation,

- autonomie du patient

Article body

introduction

Recent medical practice, research, and technology advances have enhanced diagnostic and treatment capabilities. As a result, people are living longer, but at the cost of increased burden of chronic illness and reduced quality of life (1-3). Similarly, the experience of dying has changed recently: where death was once often the result of an acute event, it has increasingly become a chronic process. Many patients with chronic disease suffer recurrent complications of their disease, leading to progressive functional and cognitive decline (4). Consequently, more patients now die in institutional settings, such as hospitals or long-term care facilities, despite most expressing a preference to die at home. In Ontario, 2023 data showed that 55.3% of deaths occurred in hospitals, while 43.3% occurred in non-hospital settings, including long-term care homes, retirement homes, private residences, and other facilities (5). Given the complexity of their conditions and evolving prognoses, clear and ongoing communication by healthcare providers (HCP) is crucial (6-8).

Advance care planning (ACP) is a proactive and ongoing process where HCPs explore a capable patient’s values and healthcare priorities in light of their health condition (9). In contrast, goals of care (GOC) discussions build upon ACP by translating these wishes into more specific clinical decisions and may occur with either a capable patient or their designated substitute decision-maker (SDM) if the patient is incapable (10). A critical subset of these discussions involves documenting patients’ expressed capable wishes, which guide future healthcare decisions (1). Patients are encouraged to designate an SDM who can make healthcare decisions on their behalf in accordance with their most recently expressed wishes. Code status discussions — such as preferences around cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and intubation — are one concrete outcome of GOC discussions (10-12). These discussions may result in a decision for “full code” (chest compressions, defibrillation, intubation, and ventilation) or “do not resuscitate” (DNR), or something in between.

ACP is associated with increased patient satisfaction, enhanced patient autonomy and more efficient use of healthcare resources by reducing interventions that do not align with a patient’s expressed wishes. Despite these benefits, only 37-62% of oncology patients engaged in ACP conversations (13). Similarly, only 47.9% of hospitalized elderly patients at high risk of death within six months engage in ACP, leading to documented wishes. Of these patients, 76.3% had thought about death before hospitalization, but only 11.9% expressed a desire for life-prolonging measures. Furthermore, only 30% of documented wishes aligned with patients’ previously expressed desires (8,14,15).

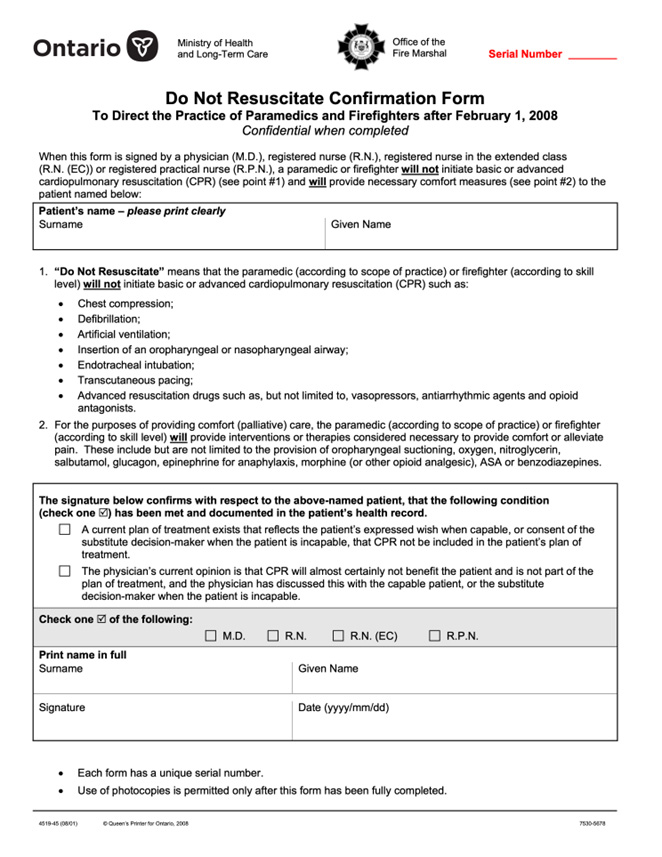

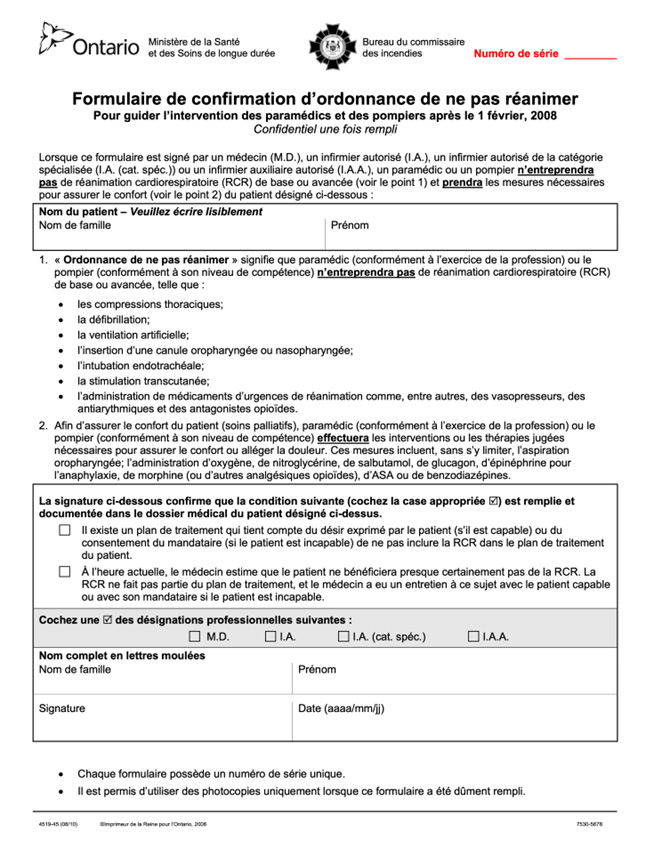

On February 1, 2008, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) introduced the DNR Confirmation Form (DNR-CF; Appendix A) (16,17). This form was created to provide clear direction to first responders, specifically paramedics and firefighters, regarding whether to initiate resuscitative efforts in prehospital emergency settings. When a valid DNR-CF is present and signed by an authorized healthcare provider, paramedics and firefighters are instructed not to initiate basic or advanced CPR, including chest compressions, defibrillation, artificial ventilation, intubation, or the administration of resuscitation drugs (17,18). In such cases, paramedics and firefighters may provide comfort care measures, such as oxygen or medications for symptom relief, in accordance with their scope of practice (18). Before the implementation of the DNR-CF, first responders were obligated to perform CPR unless the patient met very narrow criteria for obvious death. As the interventions listed on the DNR-CF reflect the standard resuscitative actions carried out by paramedics and firefighters, signed DNR-CF serve as a directive not to initiate these procedures (18,19). The DNR-CF is bilingual and can be completed by a physician (MD), registered nurse (RN), registered nurse — extended class (RN EC), or registered practical nurse (RPN) (20).

In Canada, approaches to pre-hospital DNR documentation vary across jurisdictions. While Ontario uses a standalone DNR-CF for paramedics and firefighters, other provinces integrate resuscitation preferences within broader medical orders. For example, Alberta employs the Goals of Care Designation (GCD), a standardized medical order that categorizes treatment preferences into levels of care, rather than a binary DNR decision (21,22). British Columbia and Nova Scotia use Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment (MOST), which function similarly by incorporating resuscitation preferences into a patient’s overall care plan (23-25). Saskatchewan has developed the Saskatchewan Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment (SMOST), which also incorporates a patient’s goals and values into pre-hospital medical decision-making (25). These documents are generally accessible to paramedics and firefighters, ensuring that resuscitation efforts align with patients’ wishes in out-of-hospital settings.

A study of 96 patients presenting to the emergency department showed that only seven patients were aware of the DNR-CF, and only one patient had completed the DNR-CF. Barriers to completion included a lack of awareness and discomfort with end-of-life care discussions (16). It is assumed that most DNR-CFs are completed by primary care practitioners (PCPs). Although PCPs are essential in advance care planning, discussions of goals of care (GOC) occur frequently during inpatient admissions. Particularly for patients with chronic diseases requiring recurrent hospitalizations, the illness trajectory may lead to a different outcome from those discussed with PCPs. While many studies have explored the nuances of GOC discussions, limited literature exists on the effectiveness of the inpatient-to-outpatient translation of this communication (26-30). To date, no study has examined the DNR-CF completion rates by HCPs and the perceived barriers they face in completing these forms. Here, we aimed to identify the awareness of, rates, and perceived barriers to completing the DNR-CFs among inpatient general internists.

Methods

Setting and context

This study was conducted across two adult acute care hospitals — Hamilton General Hospital (HGH) and Juravinski Hospital (JH) — within the Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) network in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. These hospitals serve the population in the south-central region of Ontario and act as a major referral centre for other areas in Ontario. The JH is adjacent to the Juravinski Cancer Centre, which provides comprehensive cancer care to patients in Hamilton.

Study Population

The participants included general internists at HGH and JH in either inpatient or mixed inpatient-outpatient settings.

Ethical Consideration

This study was designed as a baseline evaluation to inform a larger quality improvement initiative. As such, our institutional research ethics board (REB) waived a full review. All participant data were anonymized, interview transcripts were de-identified, and interviewers were assigned numerical codes.

Study Design and Outcomes

A mixed-methods design was employed, comprising an online survey followed by a qualitative focus group. The primary quantitative outcomes were: 1) the proportion of general internists who had previously completed a DNR-CF, and 2) the frequency and types of healthcare provider-related and patient-related barriers identified in the survey. The qualitative outcomes included themes related to physicians’ perceptions of the DNR-CF’s utility, barriers to its completion in inpatient settings, and suggestions for improving uptake among hospital-based providers.

Survey Phase

Online surveys were distributed to 25 general internists. This survey collected demographic information (e.g., age, sex, years in practice, and practice location), along with participants’ awareness of DNR-CF, frequency of form completion, and perceived barriers to its use (Appendix B).

Focus Group Phase

A focus group was conducted with three general internists who expressed interest following the completion of the survey. A qualitative descriptive approach was used to explore participants’ experiences and perspectives regarding the DNR-CF. A semi-structured interview guide (Appendix C), informed by relevant literature and our objectives, was developed and pilot-tested internally for robustness. The 60-minute session was conducted via Zoom and moderated by a member of the research team trained in qualitative methods. The session was audio-recorded, transcribed (Appendix D) and de-identified by the focus group facilitator (Appendix E). The audio recording and the transcription were securely saved on a password-encrypted hospital computer, and audio recordings were deleted following transcription.

Quantitative Analysis

Descriptive statistics from the survey were analyzed using Google Forms with the Free Spanning Stats. Results were summarized as proportions and frequencies.

Qualitative Analysis

Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework was used to guide the thematic analysis (31). Two independent researchers (MJ and JH) read through the transcript several times to become familiar with the content, then worked separately to develop initial descriptive codes. They met regularly to compare their interpretations, refining the codes through discussion and reaching consensus along the way. Codes were then grouped into overarching themes and subthemes. Investigator triangulation, through the use of two coders, enhanced the credibility of the analysis. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and a finalized coding framework was applied consistently across the transcript.

Ensuring Trustworthiness

Several strategies were used to ensure that the findings were credible, dependable, confirmable, and transferable. Credibility was established through independent coding by two independent assessors, with discrepancies addressed through discussion to reach consensus. An audit trail was maintained throughout the process to keep track of how codes and themes evolved, which helped ensure dependability. To support confirmability, direct participant quotes were included in the Results section to demonstrate that interpretations were grounded in the data. Finally, detailed information was provided regarding the study setting and participant characteristics allowing readers to assess how well our findings apply to other clinical scenarios.

Results

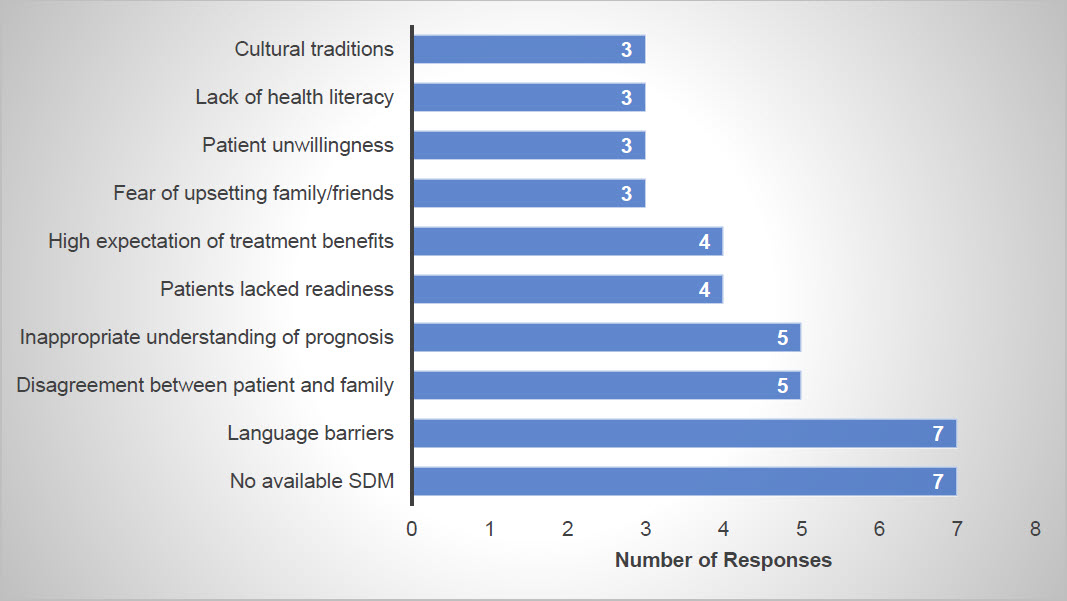

Survey

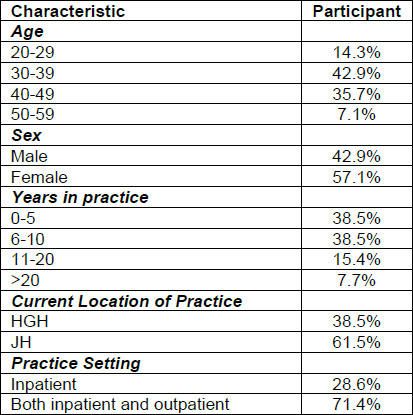

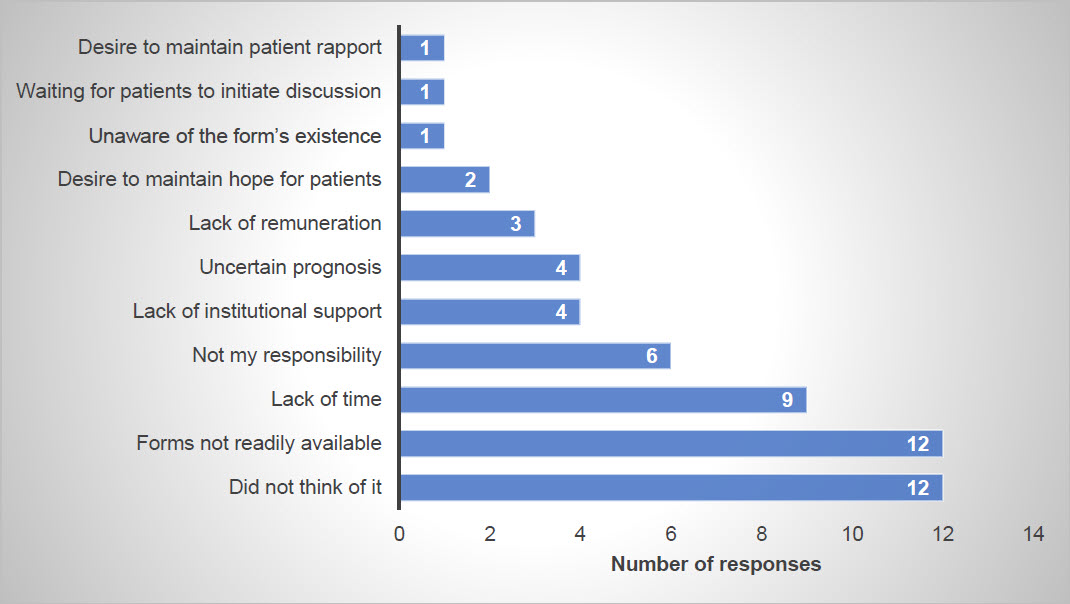

A total of 14 general internists completed the surveys. Most participants (71%) practiced both inpatient and outpatient, whereas 29% exclusively practiced inpatient (Table 1). Although all responders were familiar with DNR-CFs, only 16.7% completed a DNR-CF on discharge. None of the participants filled out a DNR-CF during the month preceding the survey. The most frequently cited HCP-related barriers were the lack of awareness and availability of the forms (Figure 1). In contrast, the most common patient-related barriers, as perceived by physicians, included lack of access to SDM and language barriers (Figure 2). As patients were not study participants, these barriers reflect physician perceptions rather than direct patient-reported experiences.

Table 1

Demographic information

Figure 1

HCP-related barriers to completing DNR-CF identified in the survey

Figure 2

Patient-related barriers to completing DNR-CF identified in survey as perceived by physicians

Focus Group

Three general internists participated in the focus group. Four main themes were identified from the discussion: general, benefits, barriers, and suggestions.

General

All participants assumed these forms were completed solely in the community setting, usually triggered by a new nursing home or hospice admission. None of the participants have considered revisiting GOC conversations on discharge to enable the completion of DNR-CFs. They acknowledged the infrequent completion of the forms in the inpatient setting, with one participant saying: “…I have never seen anyone filling out this form in a hospital” and “I thought the forms needed to be completed in the community.”

Benefits

The General Internists agreed on the benefits of the DNR-CF when caring for an incapable patient whose SDMs are unavailable. However, it is only helpful when the patient does not want any form of resuscitation. It becomes challenging when patients may wish for some, but not all, of the treatments outlined on the form.

Barriers

We identified three key themes for HCP-related barriers to filling out DNR-CF forms:

-

Knowledge gap: Physicians in the focus group stated they “did not think of it.” In addition, focus group physicians felt hesitant to complete the forms as they did not understand the medico-legal implications of completing a DNR-CF.

-

Accessibility: physicians stated that “forms are not readily accessible,” and they were not sure if it was kept on wards.

-

Outside the scope of inpatient physician: a physician in the focus group commented that completing DNR-CFs after GOC planning was “not my responsibility.”

In addition, physicians did not feel that the forms were reliable and that there was inherent redundancy in filling out the forms. The key themes we identified as patient-related barriers to having DNR-CF completed included:

-

Systemic barriers: this was most commonly identified as “language barriers.”

-

Lack of social support: physicians mentioned that patients who were unable to make GOC decisions often had “no available SDM,” posing a medico-legal challenge with completing the DNR-CFs.

The focus group participants reiterated some of the barriers addressed in the survey, such as lack of awareness of using these forms in the inpatient setting, form availability, limited time, and insufficient remuneration.

One participant stated:

“I try to find out how to get access to this form, and I couldn’t. You cannot just download it. You have to order it because it has a serial number. You can’t just give your CPSO number. You have to have an official letterhead or whatever to order this form, so I think it is really complicated.”

The discussion also focused on the role of inpatient internists in addressing GOC conversations and completing the DNR-CFs. The participants discussed that for those patients requiring recurrent admissions with declining health status, inpatient general internists are in an excellent position to complete the DNR-CFs. Internists may offer fresh perspectives on patients with recurrent admissions, particularly when specialists may be too focused on disease treatment or cure. However, for patients with complex comorbidities, participants felt that relevant specialists best addressed GOC discussions. Similarly, some argued that PCPs are better positioned to have these conversations, given their longitudinal relationship with patients. Additionally, one physician did not believe that the inpatient environment was the right time to fill out the forms.

“The patient is not in a stable point of health where the discussion should be best held. If these discussions were to be held, it would be after they were stable.”

Additionally, they expressed concerns about the redundancy created by completing the DNR-CF, particularly if the code status is already documented on the electronic medical record (EMR). Additionally, nursing homes and hospices are already required to have them filled out.

Some questioned the validity of the DNR-CFs. Providers feared that patients may face harm if the forms did not reflect current wishes. Code statuses are fluid, and reassessment with the patient and their SDMs must be possible. Furthermore, initial GOC conversations may not be comprehensive enough (i.e., providers did not address all aspects of resuscitation in their code status discussions with patients), making it hard to trust the authenticity of these forms.

“When I have that form, I don’t trust the form to be comprehensive enough to provide the care that is required to the patient at the time.”

Finally, questions regarding the legally binding status of the forms were raised and considered a barrier to their completion. Table 2 provides a summary of the themes identified in the focus group in relation to the barriers.

Table 2

Focus group subthemes in relation to barriers in completing the DNR-CF

Suggestions

The participants also suggested strategies to improve the completion rates of the forms as an inpatient. These included dedicating more resources and financial incentives. One physician suggested introducing these forms in palliative care workshops to raise awareness. Lastly, participants believe this form is not helpful for every admitted patient. They suggested the publication of a DNR-CF policy that identifies a specific demographic or set of patient criteria for whom these forms could be most beneficial (e.g., a patient suffering from the mid to end stages of their chronic illness rather than a patient admitted for a self-limited diagnosis).

Discussion

Overview of Key Findings

Our results demonstrate the low participation rate of inpatient HCPs in completing DNR-CFs at HHS and highlight specific barriers to their completion. These barriers span various domains, including personal and professional issues for HCPs, challenges with patients and SDMs, institutional policies, environmental factors, and the EMR limitations. Existing literature shows low awareness and completion rates of DNR-CFs among patients (16). Our study is unique in examining these trends from the perspective of inpatient HCPs. Combined with existing literature, our results confirm low awareness and completion rates of DNR-CFs among both providers and patients.

Clarifying Roles and Responsibilities

An important theme from the focus group was the uncertainty around who is responsible for completing the DNR-CF. While PCPs are generally assumed to complete the form due to their long-term relationships with patients, participants argued that subspecialists and inpatient providers also have important roles, especially when managing complex, chronically ill patients. Although GOC discussions often occur in outpatient settings, these conversations should also routinely happen during hospital admissions, especially as more patients face recurrent admissions due to chronic disease complications. In these situations, internists are uniquely positioned to revisit GOC discussions during hospitalization, as admissions could indicate a change in illness trajectory. Close collaboration between general internists, PCPs, and subspecialists is paramount to ensure these forms are completed at optimal times and with adequate context.

Misconceptions About Redundancy

Some focus group participants questioned the need to complete DNR-CFs in inpatient settings where code status is already documented in the EMR. However, it is important to reinforce that these forms are primarily intended to guide first responders during community emergencies. To avoid confusion, the DNR-CF should be limited to a binary directive for or against CPR and intubation, rather than including broader ACP preferences, such as ICU admission and non-invasive ventilation.

Timing and Validity of the DNR-CF

Concerns were raised about the timing of DNR-CFs and whether these forms accurately reflect current patient wishes. Participants emphasized that comprehensive serious illness conversations must proceed completion of the form, ensuring that patients and their SDM are fully informed. In an inpatient context, the optimal time to complete a DNR-CF may be after a serious illness conversation between the provider, the patient, and their family, ensuring they fully understand their prognosis and disease trajectory. Internists can play a role in reconfirming code status at discharge and facilitating the appropriate completion of the DNR-CF.

Focus group participants also questioned the legal standing of the DNR-CF. While it is binding for paramedics and firefighters under Ontario’s Basic Life Support Patient Care Standards and their standard operating procedure, other HCPs are bound by the Health Care Consent Act (HCCA) (32,33). Although section 5 of the HCCA describes that patient wishes can be expressed in any written or oral form, it also describes that “Later wishes expressed while capable prevail over earlier wishes” (34). The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care states that HCPs who follow the DNR-CF “do so at their own risk” (32). Therefore, while the DNR-CF can provide guidance, HCPs should ideally verify current wishes with the SDM.

Addressing Barriers to GOC and DNR-CF Completion

Barriers to GOC discussions are well-documented in the literature, including patient’s difficulty accepting poor prognosis, misconception about life-sustaining treatments and family disagreements (35-37). Clinician-related barriers such as time constraints, lack of long-term relationship with patients, inability to reach the SDM, insufficient institutional support, and inadequate training are also common. An important systemic-related factor is absence of an appropriate confidential space for discussions (37-39). Addressing these barriers is crucial to enhancing DNR-CF completion rates.

Educational Opportunities

Our focus group also revealed a clear need for improved education around the DNR-CF and the processes related to its completion. Participants expressed uncertainty about when and how to complete the form, its legal implications, and where to access it. These insights suggest that an educational intervention could be a valuable next step. For example, a brief targeted education session offered shortly after focus group participation — when the topic is top of mind — may be a practical and timely approach to improving awareness and confidence. As part of future quality improvement (QI) efforts, we plan to integrate such an intervention into subsequent phases of this project. This may serve as a foundational step toward shifting the culture surrounding end-of-life planning and enhancing the appropriate use of DNR-CFs in inpatient settings.

Strategies to Improve Completion Rates

Low DNR-CF completion despite participation in GOC education suggests a need for multi-pronged strategies. These may include improving form accessibility, empowering allied HCPs to complete them, defining patient criteria for form eligibility, and embedding them in discharge checklists. Completing the form upon admission and providing it at discharge could reduce redundancy and increase uptake. Financial incentives may also help increase completion rates. Importantly, increasing the frequency and quality of ACP discussions is a foundational step toward improving DNR-CF completion. The form should represent the final stage of a broader, meaningful ACP process, in which capable patients are given the opportunity to reflect on and communicate their preferences. If ACP conversations are initiated early and routinely integrated into both inpatient and outpatient care, DNR-CF completion may follow naturally. A holistic, system-level approach that prioritizes proactive, and structured ACP discussions will help ensure that patient preferences are explored, clearly documented, and effectively guide future care.

Ethical Considerations

There are several ethical implications associated with DNR-CF completion. First, while these forms are crucial for respecting patient autonomy, it is essential to recognize that patients may not fully understand or be certain of their wishes regarding DNR status until they are confronted with the reality of their condition, such as impending death. Additionally, an existing DNR form that is not updated may no longer reflect the patient’s current wishes, undermining autonomy. This highlights the need for ongoing opportunities to revisit code status discussions and update DNR-CFs in inpatient and outpatient settings to reflect the patient’s current wishes accurately.

Second, CPR and intubation may carry significant risks, including physical injuries, like rib fractures, and potential psychological harm from prolonged suffering or diminished quality of life (15). Administering aggressive interventions to patients whose preferences have not been clearly established can lead to distress for both patients and their families, compromise dignity at the end of life, and contribute to moral distress among healthcare providers who are uncertain whether the care is wanted (40,41). Providing treatments that conflict with a patient’s values can result in unnecessary suffering and erode trust in the healthcare system (42). In addition, such interventions can lead to inefficient use of healthcare resources (43). It is thus essential that HCPs conduct frequent code status discussions to clarify these risks so that patients and caregivers develop a deeper understanding of the implications of their decisions. By completing DNR-CFs through comprehensive discussions, healthcare providers can help prevent unwanted harms, uphold patient-centred care and enhance informed consent.

Third, PCPs offer continuity of care, often have deeper rapport, and are more familiar with their patients, which provides an opportunity for better-informed consent regarding DNR status. However, the drawback is that PCPs may not be available when patients are acutely ill and facing potential mortality, a time when decisions may differ. On the other hand, hospital physicians have specialized knowledge and access to the immediate clinical context, supported by interdisciplinary teams and consulting specialists like palliative care teams. Yet, they face time constraints and often lack the long-term relationships that PCPs have with patients. Finally, providing care that does not align with a patient’s values and preferences is not only ethically concerning but also represents an inefficient allocation of healthcare resources (42,43).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the small number of focus group participants limited thematic saturation. While individual instead of group interviews may have offered a broader range of perspectives, the focus group approach encouraged consensus-building through interactive discussion, which is valuable in quality improvement projects. Additionally, group settings can shape the discussions, as they may encourage consensus and limit expression of opposing and diverse views. Nonetheless, given that our study was a QI initiative aimed at identifying key barriers, achieving full thematic saturation was not a priority, and our findings still provide important insights. Future studies with larger sample size and individual interviews can improve the generalizability of our results.

Additionally, interpretation of survey responses may have varied across participants. For instance, some respondents who selected “did not think of it” as a barrier may still have considered or completed a DNR-CF in other contexts or may have selected additional barriers based on hypothetical scenarios rather than direct experience. There may also have been variation in how respondents interpreted “did not think of it” — for example, forgetting in the moment versus never having considered the form at all. The potential for varied interpretations of questions is a common limitation in self-reported survey data and reinforces the importance of careful interpretation of these responses.

Although the DNR-CF can be completed by various healthcare professionals, including registered nurses (RNs), nurse practitioners (RN-ECs), and registered practical nurses (RPNs). Our study focused predominantly on general internists as our primary interest was to explore the unique barriers faced in DNR-CF completion within inpatient settings where general internists often lead GOC discussions. However, this narrower approach to selecting HCPs may have limited the perspectives captured and overlooked barriers experienced by other providers who are also authorized to complete the forms. Future studies should include a larger range of HCPs to gain a broader understanding of the facilitators and barriers related to DNR-CF completion.

Conclusion and Future Directions

To address the issues identified in this study, it is essential to provide more opportunities for GOC discussions in both inpatient and outpatient settings, supported by reminders or strategies to prompt these conversations. Our findings lay the groundwork for future quality improvement studies aimed at implementing appropriate interventions to increase DNR-CF completion rates by inpatient HCPs. Future studies should explore DNR-CF completion across a broader range of inpatient settings, such as oncology and palliative care, and evaluate the role of allied healthcare professionals, in supporting form completion. Integrating structured ACP discussions into routine care — alongside improved provider education, clearer delineation of responsibilities, and institutional support — may help overcome identified barriers and ultimately improve the consistency and quality of end-of-life planning across the continuum of care.

Appendices

Appendices

APPENDIX B. Survey Instrument – Ontario’s MOHLTC DNR Confirmation Form: From Inpatient to Outpatient Care

We are conducting a study on Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) Confirmation Forms. Our objective is to understand whether DNR Confirmation Forms are a routine component of clinical practice.

We invite you to participate in this study. Part 1 involves a brief survey, and Part 2 is an optional focus group. Participation is voluntary. You may leave any question blank if you prefer not to answer. All information will be kept confidential. This survey will take approximately 5–10 minutes to complete. By proceeding with the questionnaire, you are providing consent for your responses to be included in our analysis.

Section 1: Demographics

-

Age

☐ 20–29 ☐ 30–39 ☐ 40–49 ☐ 50–59 ☐ 60+

-

2. Gender

☐ Female ☐ Male ☐ Prefer not to say ☐ Other: _______

-

Profession

☐ Physician (MD) ☐ Social Worker (SW) ☐ Registered Nurse (RN)

☐ RN – Extended Class (RN-EC) ☐ Registered Practical Nurse (RPN)

☐ Nurse Practitioner (NP) ☐ Other: _______

-

Medical Specialty (if applicable): ____________________

-

Years in Practice

☐ 0–5 ☐ 6–10 ☐ 11–20 ☐ >20

-

Current Location of Practice: ____________________

-

Practice Setting

☐ Inpatient ☐ Outpatient ☐ Both

Section 2: Background

On February 1, 2008, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) introduced a new DNR Standard. This change allowed paramedics and firefighters to honour patients’ previously expressed wishes using the DNR Confirmation Form (DNR-CF). This bilingual form may be completed by an MD, RN, RN-EC, or RPN, and requires a 7-digit serial number for authenticity. A DNR-CF may be completed after obtaining consent from the patient or their substitute decision-maker (SDM).

Section 3: Awareness and Experience

-

Are you aware of the existence of the DNR-C form?

☐ Yes ☐ No

-

Have you seen a DNR-C form used in practice?

☐ Yes ☐ No

-

Have you ever completed a DNR-C form?

☐ Yes ☐ No

-

Have you completed a DNR-C form during an inpatient admission?

☐ Yes ☐ No

-

In the last 4 weeks of inpatient work involving direct patient care, how many DNR-C forms have you completed?

☐ 0 ☐ 1–5 ☐ 6–10 ☐ >10

-

Have you completed a DNR-C form during an outpatient encounter?

☐ Yes ☐ No

-

In the last 4 weeks of outpatient work involving direct patient care, how many DNR-C forms have you completed?

☐ 0 ☐ 1–5 ☐ 6–10 ☐ >10

Section 4: Barriers to Completion

A. Healthcare Professional–Related Barriers

Please indicate whether the following factors have affected your completion of DNR-C forms.

Options: ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not Applicable

-

Didn’t think of it

-

Discomfort with the topic

-

Lack of training or confidence

-

Lack of institutional support

-

Lack of remuneration

-

Lack of time

-

Forms not readily available

-

Unaware of the form’s existence

-

Waiting for patient to initiate discussion

-

Desire to maintain hope for patients

-

Desire to maintain patient rapport

-

Miscommunication between healthcare providers

-

Uncertain prognosis

-

Preference to focus on treatment/interventions

-

Belief that it is not your responsibility

Other healthcare professional–related barriers (please specify):

B. Patient-Related Barriers

Please indicate whether the following patient-related factors have affected your completion of DNR-C forms.

Options: ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not Applicable

-

Patient lacked readiness

-

Fear of upsetting family/friends

-

Disagreement between patient and family/friends

-

Lack of health literacy

-

Lack of understanding of current health status or prognosis

-

Patient unwillingness

-

No available SDM

-

Spiritual, cultural, or racial traditions

-

Language barrier

-

High expectations of treatment benefit by patient or SDM

Other patient-related barriers (please specify):

Section 5: Focus Group Invitation

Would you be interested in participating in a 1-hour focus group (to be scheduled between April 1 and June 1)? Food will be provided.

☐ Yes ☐ No

Thank You

Thank you for your time in completing this questionnaire. Your responses are confidential and will be used for research purposes only.

APPENDIX C. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Do Not Resuscitate. Confirmation Form: Completion rates when the patient does not wish to be resuscitated within the inpatient and outpatient settings

FOCUS GROUP QUESTIONS

General:

-

Before this study, were you familiar with DNR-C forms?

-

What are your general thoughts on DNR-CFs?

-

What are your thoughts on its use in inpatient GIM practice? Is it helpful?

-

Outpatient practice?

-

Some responders indicated their understanding that these forms can be only completed in the community and not in hospitals. Do you agree with this statement?

-

-

If you have filled out a DNR-C form, when was that and why did you decide to fill it out (what was your trigger)?

Provider Related:

-

In your practice, do you customarily revisit goals of care and code status at the time of discharge to review patients’ preferences if he/she were to deteriorate or have a cardiac arrest in the community?

-

Do you think this should be done?

-

Do you think this would be an opportune time to fill out DNR-C forms?

-

-

Whose responsibility do you consider it to be to complete the DNR-C forms?

-

If you think it is not your responsibility, why?

-

-

Do you have any further thoughts on barriers to filling out DNR-CFs?

-

What is the best way we might promote clinicians to fill out more DNR-CFs in their clinic or inpatient practice?

-

What process would you suggest for ensuring these forms are filled out for patients when there is an appropriate trigger? Should other allied health be involved? Should we include it the discharge order set?

-

How do you think institutional support can help with filling out the DNR-C forms?

-

One of the most commonly cited provider related barriers was “I did not think of completing the form.” What are some factors leading to this? What are some ways that can be used to remind physicians of this form?

-

What are some ways the visibility of these forms can be enhanced?

-

Some cited “lack of time” as a barrier. How can we help to address this?

-

Patient-related:

-

How can we improve the patients’ awareness of the forms?

-

A cited barrier is lack of understanding of the current health status/prognosis. How do you think completing the DNR-C forms can lead to improved communication with patients to ensure appropriate understanding of their status?

-

How do you think lack of patients’ health literacy can impact the completion of DNR-C forms? How can physicians aim to improve this literacy in this case?

Appendix D. Focus Group Transcription

Facilitator = F

Participant 1 = P1

Participant 2 = P2

Participant 3 = P3

Session Begins After Jessica Leaves Zoom Meeting

F: Just to reiterate, thank you everyone for signing up and joining the focus group, I know the research group really appreciates it. Discussion today will focus on some of the barriers to completing the form and hopefully provide feedback for the tool itself and potentially other tools in practice that are recognized as similar or used in similar circumstances. This would all be to work in favour of both patients and practitioners.

In general, were you all familiar with the DNR-C forms before the study began and you were prompted to participate?

P1: No

P2: It’s the community ones that come from the nursing home?

F: Yes

P2: Yes

P3: Yes

F: For those of you who have had experience with the forms, what is your general thoughts, do you find that they are helpful for inpatient practice?

P3: We are talking about those DNR forms that come with packages from nursing homes and long-term homes? My general view on them is it is helpful because often times we don’t have any information from family, nothing directive when a patient is confused or has dementia. So in these cases, having a form that says DNR is helpful guiding our decisions. My biggest trouble with the form I would say is still what the medical legal status of those documents are. I’ve had two supervisors when I was training telling me that those are not appropriate legal documents and even in the case you cannot reach someone, you should maintain that they are so called “full code”. Whereas, I had someone else say ‘look if you have that form and have no reason to doubt its validity, you should follow that as your directive. So that is my main concern with the form, but I do think it is useful without other relevant information.

P2: For the form, same as was already said, it is really helpful when someone can’t communicate what their issues are so I know that they are not for resuscitation. I know there’s kind of a long list of things that is says they are not for. That’s where it starts to become muddy, because often times you speak to the POA, despite them having that form, they actually are for ICU level measures and some of the things that are on that form that say ‘are not for any kind of assisted ventilation’ but then they are for noninvasive ventilation. So it becomes a little bit muddy. I haven’t had anybody contest the actual ‘do not run a code’ but I don’t know where to stop. When I have that form, I don’t trust the form to be comprehensive enough to provide the care that is required to the patient at the time.

F: So typically, in your experience it is coming from a nursing home versus being drawn up and done in hospital?

P3: You can do them in hospital? I have never seen that.

P2: I have never done them in hospital. But because it is a standard, I’ve witnessed it being done in nursing homes before on certain rotations in medical school and it wasn’t a particularly comprehensive discussion with the family. So the family don’t fully understand all the different levels of what can be offered and when you have that conversation when they get to the door and you’re admitting them, often times some of the things that the form says they are not for, they actually are for that kind of care.

P3: I would agree with that and it was not infrequent that I have found that once discussing with the family there is a complete reversal than what is on the form.

F: Which creates issues with inconsistencies?

P3: Yeah, I mean if we can reach the family that’s great but because of all these reversals that often do happen, it makes me feel a bit uncomfortable following the forms directive having those experiences.

P1: For me it was kind of new because I am new to the Canadian healthcare system so I was not familiar with how things are done but I work in palliative care, so we have many patients who are not wanting to be resuscitated so I was surprised you need this official form, the DNR-C form in addition to DNR form or Will to make it valid and honour their wishes. It’s only one year since I started working here and I have never seen anyone filling out this form in hospital.

F: So, what I am hearing is none of you have been seeing it completed in hospital, and when you do see it completed there are these inconsistencies, and it is not all comprehensive for what is actively going on or out of date.

P3: I would agree with that statement, and I would also say that I do not necessarily believe that the inpatient environment is the right time to be filling out these forms. Obviously, we address code status quite frequently, especially those patients who are critically ill, but perhaps my understanding of this is that with all these forms, if they come back in the future that we have a clear directive, but I mean it’s a prolonged discussion, we need the family there. The patient is not in a stable point of health where the discussion should be best held. If these discussions were to be held, it would be after they were stable. Perhaps the physician knows them well, and to be frank, I do not think the resource limitations that we already face on internal medicine really provide us the time and opportunity to do such an important discussion in hospital. There would have to be dedicated resources and probably some financial incentive for physicians to be doing this in inpatient or outpatient because it would require substantial resources.

F: That touches on my next question regarding outpatient services, similarly you believe that due to the planning process in hospital, there would have to be some kind of resources and incentive to ensure this discussion is had?

P1: I was wondering, we have so many goals of care discussions in palliative care especially and also in internal medicine at some points and I think it would make sense if a patient goes home after their stay in hospital to give such a form to the patient to avoid having things done to them that they do not want. If family would call emergency services because they were seriously ill or deteriorating and they opted in the goal of care conversation during the previous stay in hospital that they want to be DNR or AND, I think if this form is needed for his wishes to come true than we should give them this form. I was just not aware that it exists and even now that I know it exists, I try to found out how to get access to this form and I couldn’t. You cannot just download it, you have to order it because it has a serial number, you can’t just give your CPSO number, you have to have an official letter head or whatever to order this form so I think it is really complicated.

F: So regarding inpatient and the ongoing changes in inpatient care, you find it is not necessarily helpful as things are constantly changing?

P2: I would be open to filling out the form. One of the things I am concerned about is that the form has a laundry list of things they do not want done to them and I don’t think it is accurate. I would be okay with filling out a form if it was going to be an accurate form as I wouldn’t feel like I was doing an appropriate service to the patient if I am just getting them to sign a form when I know that half of those things on the form are not actually in keeping with their wishes. If there was an alternate form that you could outline whether or not they would want the various interventions, be it noninvasive ventilation, dialysis, or things like that where it becomes more of a grey area and often times you get different people who are all “not for resuscitation” that all want different things, I would be okay with filling it out. I do not think it would be too time consuming. Obviously, a financial incentive would be nice but I think the form has to be useful on an ongoing basis because a lot of the times we fill out those forms even the admission orders with the admitting goals of care and the next time they come in, you need to do it all again. If it is not an enduring form, it really is not useful.

P3: My concern about filling these forms is that obviously we already do code status, we did forms before Epic and now we do the code status on Epic. The reality is we already have those discussions on Epic and document that on our system. So the question is, what value do we add by filling out a different form so we have the advanced directive if they come back again. The other question is, if they are already doing this form in nursing and retirement homes when patients are more stable, presumably there is more time to think and discuss and have a chat about their code status, why are we also doing it here? If the patient is not in a nursing or retirement home, is the inpatient internist doing the form better or more appropriate than having a longer conversation with their family physician who knows them better? This is my hesitancy about us filling out forms. I have no problem doing code status, and fill them out all the time, but am I adding value to patient care by doing yet another form and even if it’s done, if we are doing it in an acute care setting where things make change substantially during their time there as an outpatient, will I truly believe that this was there last known wishes when it was done in this acute care environment? If I am still not sure, then I will still ignore it anyway and have to call the family. If there isn’t a kind of legal precedent or something to back me up from a legal perspective to use it, I would be hesitant to use this document to guide my decisions similarly to existing forms that are in the outpatient setting.

F: Before this study and focus group, it was everyone’s impression that these were completed solely in community setting?

P1: Yes

P2: Yes

P3: Yes

F: As none of you have personally completed the form, have you ever been present with a colleague or supervisor who had completed this form?

P3: Never

P2: I have seen it done before by the charge nurse of the nursing home with the POA saying ‘if they go to hospital do you want them to be resuscitated with electric shocks and life support’ or something along those lines and they say no and then the staff say sign this form. It was not really a conversation about all the other things that the form entails. It was just do you want them to undergo CPR, do you want them to undergo invasive ventilation, if no, fill out this form but the form actually has about ten different interventions that it says you’re not wanting and people just sign it. I believe I saw it about two or three times. It was not a comprehensive discussion by any means.

F: For those situations, what was the trigger for the staff member to complete the forms?

P2: New admission to the nursing home.

F: Regarding your own practice, do you revisit goals of care and code status when discharging the patient?

P3: Nope. Not on discharge. Never.

F: No discussions of potential for deterioration or cardiac arrest or anything like that?

P3: Not on discharge.

F: Does anyone think this should be done?

P3: I do not.

P2: I have never done it on discharge, I do it routinely on admission even if they are like twenty with a toenail fungus just so that I can say that I had that discussion and then if they are sick and actually deteriorating, then I have a more detailed discussion while that process is going on. And oftentimes at that point, the goals of care are completely swapped to a comfort care model, and that’s when palliative care then gets involved, and they often then start going down the route of hospice and stuff. So, it becomes you know, there’s a difference in their goals of care, but also there’s a difference in their trajectory and they’re not necessarily going back to a nursing home or whatever. Those are the only times where it happens. So, I’ve never done it on discharge.

P1: I have never done it on discharge. I’ve done it during the hospital stay, obviously. But my understanding now with this form is like even if they are fully palliative and if they go home, I did some reading and it looks like you need this form in order to prevent paramedics to perform CPR. Even if you are fully for full palliation, you need obviously this form in order if paramedics come to your place. So, this triggers my thoughts on if we had a goal of care discussion in hospital and the patient goes home afterwards, we might need to hand out this form in order to honor the goal of care discussion we had earlier because the goals of care, they don’t end when the patient is discharged, if they are going to a hospice or if they go home with palliative care services.

P3: So, if they go home, I mean, there’s probably family around and then they’re not going to do CPR if the family says don’t do anything. They’re in a hospice facility, they’re also not going to do anything because that’s very clear. And then if they enter a nursing home, they have to have a form then anyway. So as soon as the patient enters the hospital, the physician will reassess if the patient is just readmitted and then the form will be done in palliative. So, it seems like the need has already been filled where necessary, if that makes sense. I agree with you that in certain cases that might be necessary, but in those cases it seems like someone already does it.

P1: Yeah, it might not happen very often, but it just recently happened that there was a patient. It was a

weird case, like a patient was discharged home and then was awaiting hospice and then while being transported to hospice was ordered so they came and deemed the patient to be not stable enough for just transport, though they called paramedics and the paramedics basically performed CPR on this patient that was just for transfer to hospice. So, in this case, this form would have helped. I don’t know. It might be very rare case though.

F: Based on the research and some of the things that have been covered, like you said, one of the circumstances that often happens is just regarding paramedics and in terms of their knowledge of the patient and if there is any change in code status, it has to be coming directly from a physician. This form essentially just provides them some confirmation so they can respect patient’s wishes. That’s often one of the benefits in kind of keeping with the patient wishes.

P3: But again, are we speaking about people coming from their own homes or from facilities? Because I think there is a substantial difference.

F: Right. Because if they’re in facilities, then the care team is already aware and can inform paramedics themselves.

P3: Correct. And if the existing research you’re referring to at facilities where such processes were not in place and then at this research facilitated that changed, right? As opposed to people who are at home, especially those with other family members, I’m not sure if this applies. I don’t think paramedics will do CPR if the family runs out and says don’t do anything that doesn’t want to get done. I could be wrong, but I would guess they would not do anything.

P1: I would hope. I don’t know how the rules work.

F: And for your understanding of the forms, where they are completed, whether it’s community or hospital, whose responsibility do you consider it to complete these forms?

P2: Ideally, it should be the family doctor, although I know it’s often the charge nurse of the nursing home that has that conversation. But it should be done when the person is stable and if possible, if they can participate in the conversation, it should also be done at that point.

F: And in terms of any further thoughts on barriers in filling out the forms, I think initially in the conversation, we talked just about kind of the legal logistics as well as the resources and the ongoing changes while in hospital and I think you guys have all kind of touched on multiple barriers in your own personal practice that you’ve recognized. So, we’ll move on. In terms of promoting clinicians to fill out more forms in their clinic or inpatient practice, do you guys suggest that there could be a trigger or added to some kind of checklist?

P3: I think you need to first convince clinicians that this is going to improve patient care. And I don’t think, in my mind, even from our conversation it been clearly established that we are addressing a clear need. And if we are, what is the specific population we need to address it? I fully acknowledge that these forms are helpful, and I think there are certain populations in certain circumstances, but the reality is we cannot be having physicians doing these forms on every person that comes on internal medicine. That is not feasible and will never be picked up. So, the question is, in what specific circumstances are we identifying where these forms could have potentially benefited patient care? And if you can find that population, clearly define it, have that trigger, for example Epic, and physicians agree with those, then I think you may have some uptake. But certainly, a pan form policy is not going to work out well. Even an academic center with lots of residents, that is not going to fly very well.

P1: I totally agree. It couldn’t be done on everyone, and it makes no sense to do it for everyone. But I think one group could really be the ones that you did the goal of care conversations with, and they said, okay, I don’t want CPR, and I’m not for CPR. That could trigger filling out this form.

F: And I hear just like you’re saying, in terms of the clinicians and the resources of even residents, would there be an opportunity that potentially allied or nursing could assist? Or do the barriers stand regardless as the blanket forms would not be appropriate?

P2: I think that would be even more of a challenge because I feel like despite the fact that there’s a doctor shortage, nursing shortage, I feel like there’s even less allied health support. Sometimes it takes me seven days to get a social worker involved in the person’s care, and that’s what they needed from the beginning. So, I think that asking additional Allied Health team members, those ones with the training, such as social workers, to be involved would be virtually impossible in the current climate.

P3: I entirely agree with your point, and beyond just the resource limitations, especially if you’re talking about addressing code status in patient environment, when a patient is acutely ill, you need a physician to address this conversation. There are so many medical pieces that an Allied Health member will not be able to answer. And my personal experience mostly being at Hamilton General, is the nurses do not know those patient details. They will not be able to address even the current clinical status, to be honest. So having them doing such an important conversation is not feasible, at least in Hamilton.

P1: It might be helpful though, to gain access to those forms because I would have asked Allied Health where I can get those forms like for those little administrative steps.

P3: I definitely agree. They have to be readily accessible. I literally have to either press print on a form available on the computer or it’s right in a box beside me like those CCAC forms. Otherwise, it definitely won’t get filled up. It has to be very easily accessible. I haven’t filled one out myself, but if there are truly ten check boxes on it, it’s also not feasible. It’s not.

P2: They’re not check boxes. It’s just a laundry list that you just sign at the bottom.

P3: Oh it’s literally just one DNR form, There’s no differentiation?

P2: It’s one big form and it’s very ambiguous. And it actually just says no assisted ventilation. Like it doesn’t specify what that actually entails. So, a lot of the patients that have signed that form or the family sign that form, in the end they actually are for like optiflow and stuff like that. So, it’s not even accurate.

P3: That’s another major barrier, I would say.

P1: It’s really for someone who is basically like that. Like it’s not for someone who is not breathing well or something like that. It’s not for end stage COPD who might want some form of BiPAP or CPAP or like optiflow or whatever, but it’s more like if someone has a cardiac arrest or something, and then it’s kind of clear. Like it just states what’s not, what won’t be done. And those are the things that you usually do when you perform CPR. Like, I have it here. No chest compression, no defibrillation, no artificial ventilation, but it does not say, okay, what kind of artificial ventilation. But to me, this form won’t exist if it’s too specific. Like, you cannot specify with one form. Like this patient would like to be on optiflow or would like to have BiPAP, but not for intubation. I think that would not be feasible.

P2: It also says, like, no transcutaneous pacing, no advanced resuscitation drugs such as vasopressures, right? And that’s often not the case. And some of these patients are for pressors and ICU management and somebody with tachy brady, they actually sometimes need transcutaneous pacing, and they are okay with that while they’re waiting their pacemaker. So, again, I don’t think it’s an accurate form, and I don’t think it’s accurately filled out because it’s kind of like if their heart stops, we don’t want you to do anything. But the form actually encompasses much more than that, and most people aren’t aware of that.

F: So, what I am hearing is It’s too general to the point where patients are coming in and actually correcting it at the time of needing care and saying, actually, we would like this and that excluded from the DNR. It’s general to maybe negate having to go through with every single patient, but because it’s so general, when individualized with patient care, they are going back and saying, no, we disagree with the form.

P2: Exactly.

P1:I think for the patients who are not for ICU and for AND or DNR, I think if you can check both of those boxes, no ICU, no DNR, then you can fill in this form. But if they are for ICU, then it’s hard to fill in this form.

P3: I agree with you to some extent, but I do believe that because of the lack of detailed conversation that P2 has outlined, from what they observed, people don’t know what ICU might entail. As they said, what if you just need to go to CCU for temporary transcutaneous pacing because they’re on a beta blocker and as soon as the beta blocker wears out, they’re totally fine? Right. Or, you know, they have really bad pneumonia, they don’t want to be tubed, but they just need temporary BiPAP to pull them over? Are you saying that I’m just going to go with this form? No. So I’m going to still call the family, I’m still going to have to have a detailed discussion, and then this form doesn’t change anything except I have more work. So, I think that you have to have that conversation in context of the patient’s current acute illness, at least on medicine with the patients we see. And no form will negate that requirement except for being truly palliative patients and as you say, that’s more of an issue of paramedics not MDs acting.

P2: Yeah. To be honest. There is a role for the form, like, when you cannot you know, when the patient can’t speak for themselves and you cannot reach the next of kin, I’m happy I have a form to know they’re not for resuscitation. So, I know to at least stop at running a code. But then there’s that ambiguity of where do we go before that point in time? But at least there’s something where you can say, I know this person definitely did not want to be resuscitated and most people also believe that needs to be artificially ventilated, so I feel like there’s at least something. But yeah, I don’t find it reliable by any means.

P3: P2, do you know if the forms are legally binding, though? Because that’s still my concern. Obviously, the situation would be very rare when this happens, but what if this form was followed and the family shows up late and be like, this person clearly want to be resuscitated. This form is not what we consider a legally binding thing, and therefore, I don’t think you’d actually get in super big trouble, because you still have best intentions. But I think that’s the fear for some people looking at this form. One of my supervisors told me that you can’t follow it.

P2: There’s a 2017 news publication. I don’t think they’re actually legally binding from what I can see.

P3: So does that mean I could get in trouble if I follow and have no collaborative information? So, let’s say you do have a DNR. You have no collateral. You assume they are DNR, they die and then this patient clearly, very, very clearly from a collateral family, everyone’s like, there’s no way this patient would die, they told me, like, a week ago and then you get sued. And this is why I see all these patients with DNR forms still taken to the ICU because they have no collateral and then the family shows up and then 24 hours later they become DNR. So until I think part of this, you need to have that legal status verified. This must be a legally binding document within certain criteria or else you will still have many physicians pulled out because I’m not protected by just following this form.

P1: Or might it be the other way around? Like if you have a bad outcome after a CPR and there is a form and you didn’t pay attention to the form, could someone blame you as well? So, I don’t know.

F: Some people in the study cited that they did not think of completing the form, but I believe we’ve touched on it a couple of times. You’d rather check in with the family and patient you know well, aware of their wishes while actively in hospital than look to an ambiguous form from a care and legal perspective.

In terms of visibility of the forms, I’m hearing that the accessibility issue is more from having to submit for it versus having it readily available. Is that fair to say?

P1: Yes.

F: And then some people who were familiar with the forms, whether in hospital or community, cited lack of time as a barrier. Would you agree?

P3: Lack of compensated time. The reality is we have a lot of work and certain things compensated better than others. I think if there was very clear value and considered routine part of care, we would find time on specific patients. We all do code status discussions when it’s important of course, we’ll carve out as much time as necessary, and sometimes obscene amounts of time. But if you are asking it to be done routinely on patients where it’s not acutely indicated, you will need to financially compensate positions for their time for this to be feasible. That’s my opinion,

P2: Yeah, and it also depends on the day. If you’ve got thirty-five acute patients and someone decompensating on the ward, there’s no chance that my priority is going to be to get to this form.

P3: I think P2 alluded to it earlier the current landscape with Allied Health, but it’s the same with MDs right now. Everyone’s stretched, everyone’s burned out. There’s lack of coverage everywhere in internal medicine, you know, the hospital shutdowns you see on the news at many places are not just a lack of Allied Health coverage, but also a lack of MD coverage. And I think that we are going to continue to stretch them for the next little while, at least locally. The patient volume certainly isn’t lower than before. If anything, it seems to be higher. So, I think if you’re going to be introducing a new piece of work for physicians, a) you’re going to have to very much convince them that this is going to improve care, and B) find some sort of compensation, likely financially for this to happen.

P1: I think for the very for the few cases where it’s really clear, like you had the goals of care discussion and they don’t want ICU, they don’t want CPR, then I think if you had this form available, it won’t take long to put your signature on it because you don’t have to fill out many spaces on this form. So, if this is not clear, then this form is not very helpful, I think. It’s not useful for every patient. It’s only useful for a certain group of patients, and then it’s only useful for the ones that are not ICU, not CPR, and then it won’t take long to give the signature if the form is available.

F: So potentially, the institution could support, through maybe collaborating with physicians to develop a specific demographic that this form could apply to, so that if there was some kind of discharge planning, that there may be a prompt, if anything. So, there is that trigger, whether it’s through charting or through patient meeting the criteria, so that you’re not having to create this for every inpatient in high acuity because the resources just aren’t there. Maybe a specific discharge prompt because otherwise it’s just very low priority to do as part of someone’s general discharge.

P2: Yeah. And I think the other trigger is, depending on which facility you’re in, ICU means different things. Right? Sometimes you need to go to ICU just so that you can get the nursing care that is required, because you need frequent blood work or whatever it is, whereas other times that would be a stepdown unit or just on the ward, depending on the nursing situation. Not infrequently and I would say about 95% of the time over the last two years, we’ve had nurses call in sick almost every day and the nurses are down to six to nine patients each, they can’t provide that kind of care. So, when we’re saying not for ICU, we need to also clarify what does that mean medically for their care, not just the location.

P3: Yeah. I think I’d be much more compelled to fill the form, as you suggest, in certain patients on discharge, if it was not the current form. Like you guys remember the old post forms we had at HHS? Now, certainly those forms are not perfect, but they allow the physician the ability to kind of describe different levels of care that was just not a yes or no. It was not binary and allowed for written text to describe what was discussed and specific elements of care that you would want versus not want. And I think for me at least, to feel comfortable filling out this kind of form, that kind of level of detail is required, at least the option to have that kind of level of detail for me to fill out such a form. What if they just need to go to ICU for insulin infusion? Right? I’m not going to stop them from going to ICU. That’s too black and white. And so, if all these exemptions exist then the form is not very useful. I do think it is possible to convince physicians to fill out these forms on certain patients where the code status is going to be a major issue on readmissions, but more so it has to be a more detailed form and that won’t really make an impact locally in Hamilton. Like if they’re always in the same region, because you have that information online. Certainly, if they visit hospitals in multiple healthcare regions, it will be very valuable and so, yeah, I think that’s something to consider as well, because at least in Hamilton, most people are getting their care just in Hamilton, so the added value is a little bit less.

P2: Yeah. And working both in Hamilton and in the community, those paper ones that you fill out, I use those the most and I find those ones much more helpful because then I’ve had a discussion. I could say, someone comes in with AKI and they’re going in the wrong direction. Yes, they’re for dialysis, no, they’re not for pacing or whatever. Like if your potassium is off, then I know that we do certain things and not other things but it’s a very detailed discussion at that time and in that clinical situation, right? Long term, if they were on dialysis and they determined they no longer wanted to be on that, then again, that form would need to be changed. So, it needs to be something that’s fluid and reassessed, and it should be reassessed as an outpatient, not when they come in. And at the time of discharge isn’t unreasonable, but oftentimes with the turnover, and I’m not exaggerating here, some days I have nine new patients and four discharges, plus all the other patients that need to come in, I don’t think that it’s feasible to be doing all of that extra work.

P3: Again, I would reiterate that I think that the most appropriate location for this is outpatient. It is a shame that we don’t have the time to do it on discharge. There are certain patients that benefit and maybe in certain environments we can squeeze out time, but I’m cognizant of the fact that we are blessed with having multiple learners running around trying to do stuff for us and the reality is, anywhere outside of the academic center, it’s just one person running around doing all that work. And so, to dedicate someone to spend the extra time to do that while you’re answering calls and seeing 30 to 40 patients, which I understand is the workload in many community centers now up to 40 patients solo, it’s not very realistic. So, again, I do think focus on the outpatient environment is where I would focus on getting the forms done.

P2: I think we also just need to verify the support because more and more doctors are leaving the outpatient environment, period. And then that becomes even more of an issue because then we really don’t have a primary care physician at all to be having those discussions. So, if that needs to be a trigger, I’m seeing more and more the patients just don’t have family doctors, which becomes very challenging because they keep coming in and you keep treating them, but you need somebody to keep them well outside of the hospital and they’re just lacking in that capacity. So it’s hard to kind of figure out exactly who should fill out the forms, but definitely as an outpatient would be beneficial. But if there was a trigger to say ‘this person doesn’t have an outpatient, anybody’ then maybe we really should be filling out the forms. But again, it would have to be something that is accurate.

P3: Wouldn’t it be nice if they had this in clinical connect, so if you could see it across different systems?

P2: It would be nice.

P1: It would be perfect. The paramedics, I think the form is mainly for the paramedics coming on the scene and they don’t have access to epic and all those clinical connect and everything.

F: And then the last part of our discussion really is just about the patient side of things, because, like you mentioned, there are certain cases where patients would benefit from receiving these forms on discharge, and also in the community and outpatient settings. Is there anything you can think of to improve patient awareness of these forms? Maybe not completing the forms with them but discussing it.

P3: I think what shocks me the most is how often I run to patients, as P2 does, I talk about code status, at least mention it on every admission, and it shocks me how many patients have never had this discussion. You’re eighty-five with ten comorbidities on twenty medications and yet nobody spoke to you about code status. I’m not in the right position to have an in-depth discussion with you about this at that moment, so the fact that there is not awareness in general in the public about the need to have a discussion about code status, it doesn’t matter what your decision is, but the fact that they’ve never thought about it, despite being at high risk for it, is my major concern. And I think these conversations and thoughts take a long time to process. People cannot answer on the spot. They can’t even answer when you give them their whole hospital admission. So that’s the other issue when it comes to establishing these code statuses beforehand, the patients have never even thought about it before, so to force them, if they’ve never thought about it before, to make kind of a decision before they go is also probably not appropriate. So, I think the issue more lies and general awareness, the patients about the problem to begin with rather than these forms specifically.

P2: To be honest, when I have those goals of care discussion, because it is on admission, I always approach it in a lighthearted manner unless I truly believe that they’re going to decompensate within the next 24 hours hours and then it becomes a very serious conversation because it frightens a large proportion of the patients that I have that conversation with. And oftentimes it is the same response that, oh, I never thought about this before. Some people are just unwilling to answer, and I say, okay, you know, talk to your family. Some people at least know that they don’t want to be on long term life support. But when I asked them, would you want to be on it for a few days? Almost everybody says yes. So even just trying to figure out whether or not they would want to have that kind of intervention, a lot of people are still on the fence. So oftentimes I will document not for long term life support, okay, with the short course and then reassess because that’s what they’ve specified. It’s not comprehensive by any means, but at least it’s a starting point and then there needs to be further discussion. And then they come in again six months later, and I’m the only person who’s ever talked to them about it and it’s the same situation. So, it’s just this revolving door cycle and they don’t want to process it until things get really bad.