Abstracts

Abstract

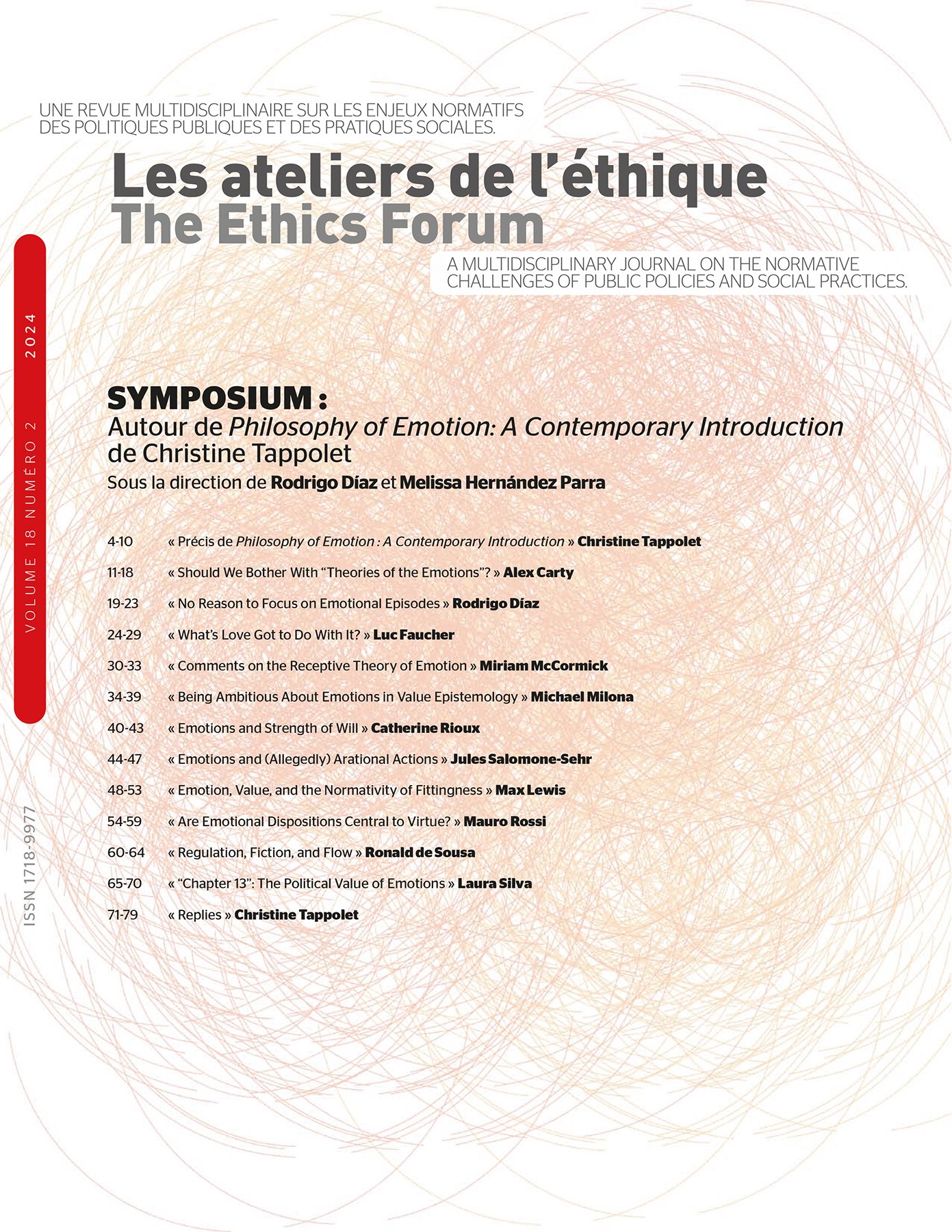

This text consists in replies to the commentaries on my book, Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction.

Résumé

Ce texte contient des réponses aux commentaires portant sur mon livre, Philosophy of Emotion : A Contemporary Introduction.

Article body

Introductions are not, as a rule, the occasion of book symposia. I am thus particularly thrilled and thankful that so many excellent philosophers—almost as many as the number of chapters!—generously volunteered to write a commentary on my book. Because it consists in a quite opiniated introduction, which contains a great number of arguments and claims, it does not come as a surprise that most of the commentaries involve objections. I hope that my replies will shed light on the thorny issues that are raised by emotions. My discussion follows the order of the chapters on which the commentaries are focused.

Let me start with Alex Carty’s remarks. Carty underscores that one can doubt that emotions have essences. He rehearses Amélie Rorty’s (1978) skeptical argument against the view that emotions have essences. The lucid presentation of this argument is a useful complement to the book. It is not entirely clear whether Carty endorses the argument, which is in fact quite controversial. But Carty is certainly right that the skeptic’s position regarding emotion theories is worth considering. There are two ways to respond to skeptical arguments of this kind. One consists in objecting to their premises—for instance, by pointing out that the fact that the repertoire of emotional terms we have depends on social factors fails to entail that emotions lack essences. The other strategy is to show that there are viable theories of emotions. Thus, I note in the book that before concluding to the truth of the view defended by Jon Elster (1999), according to which it can be shown on the basis of counterexample that none of the features that are thought to characterize emotions are necessary, one has to consider the prospect of the theories that have been offered. It is only if such theories fail that we should give up the hope of spelling out the nature of emotions. The same is true of Rorty’s skeptical view. It is only if no positive account of emotions works that we would have to conclude that emotions have no essences. What I argue in the book is that the receptive theory is a promising account of what emotions are.

As explained in chapter 2, a classical distinction in the philosophy of emotions is that between emotional dispositions (the disposition to experience fear when seeing a tiger, for instance) and emotional episodes (the emotion you experience when you see a tiger, for instance). Rodrigo Díaz reluctantly accepts this distinction. He mentions that the fact that an emotion persists over a long period of time does not entail that it is a disposition. This observation is correct—even if emotional episodes tend to be short term, there is nothing that makes it impossible for an emotional episode to last for quite long periods of time. But this does not show that we should stop making the distinction between emotional dispositions and their manifestations—that is, emotional episodes. In any case, what Díaz objects to is the thought that emotional episodes should be the focus of emotion research. More precisely, he objects to a line of argument that would take us from the claim that emotional dispositions are partly understood as dispositions to experience emotions to the conclusion that emotional episodes should be the focus of emotion research. Let me make clear that I fully agree that emotional episodes should not be the only focus of emotion research. Both emotional dispositions and emotional episodes are of interest. Indeed, the reason for being interested in both is that emotional dispositions are only partly understood as dispositions to experience emotional episodes. As I mention in the book (p. 32), what appears true is that emotional dispositions are standing states that have implicit representational content. The idea is that your fear of tigers, for instance, implicitly represents tigers as dangerous. This, in any case, is an assumption that explains why when seeing a particular tiger, you experience fear. Whether this suggestion is on the right track or not, emotional dispositions clearly merit more attention than one might think. However, to fully understand what emotional dispositions are, we need to have a clear idea of what constitutes the emotional episodes they give rise to.

Let me thank Luc Faucher for his useful comments on the debate regarding whether love is a social construction or a natural kind. His remarks will help readers in answering one of the study questions mentioned in chapter 3! What he objects to is that a discussion of the arguments for and against constructionism and biological determinism is required to argue that both conceptions take emotions to be largely plastic. I agree that only a brief presentation of the two conceptions would have been sufficient to make this point. Strictly speaking, the conclusion of chapter 3 is that the arguments for both constructionism and biological determinism fail, so that the most plausible view is that emotions are shaped by both biological and cultural forces. The claim about plasticity is a further point. Faucher also holds that emotion regulation and more precisely emotional intelligence should have been given more space. In the book, I focus on the regulation of emotional episodes (chapter 11) and the calibration of emotional dispositions (chapter 12), leaving aside elements of emotional intelligence, such as the ability to perceive one’s own emotions. Thus, Faucher’s informative presentation of the different aspects of emotional intelligence constitutes another useful complement to the book.

Let us jump to chapter 6. Miriam Schleifer McCormick raises questions regarding the account of emotions sketched in that chapter. In particular, she asks what I mean by the claim that the content of a representation matches its format. She is right that a lot is packed in the passages she quotes. What I have in mind here is an argument proposed by Jacob Beck (2012, see also Tappolet 2023) that takes us from the claim that representations that have an analogue format, in the sense that they share structural features with what they represent, to the conclusion that they involve nonconceptual contents. Analogue representations involve a magnitude (the rate of rotation of the watch’s hand, for instance), which is isomorphic with what is represented (time, in this instance). Analogicity, as it is understood here, is a syntactic and not a semantic feature of a representation. It characterizes the representational vehicle, rather than its content. Beck’s argument is that there are reasons to think that analogue representations have nonconceptual contents. This is because analogue representations fail to conform to a semantic constraint, which states have to satisfy in order to count as having conceptually articulated contents. This constraint, known as the generality constraint, requires that the content constituents of such states be able to be recombined in any semantically acceptable way so as to form the content of other states. Insofar as your beliefs involve conceptual content, it must be true of you that if you believe that crows are black and you believe that swans are white, you are able to form the belief that crows are white. Given this, the argument for the claim that analogue representations have nonconceptual content is that such representations fail the generality constraint. This can be shown by considering pigeons’ number representations. Because pigeons’ representations of number have an error rate that is proportional to the size of the number, so that they are reliably able to discriminate numbers only if their ratio does not exceed 9:10, they fail the generality constraint. Thus, they are able to represent the fact that 38 pecks are fewer than 47, and the fact that 40 pecks are fewer than 50, but they fail to discriminate between 38 and 40 pecks. Thus, by contrast to what the generality constraint requires, pigeons do not seem able to represent the fact that 38 pecks are fewer than 40 pecks. As Beck argues, this is true of all analogue representations. Indeed, he argues that the fact that representations are analogue and noisy, so that the bigger the represented magnitude is, the more failures of discrimination there are, explains why they fail the generality constraint. The suggestion I make is the same is true of emotions. The idea is emotions are plausibly thought to have an analogue format involving nonconceptual contents, since their intensity covaries with the degrees of the represented values.

Schleifer McCormick raises another question. She wonders whether emotions always depend on cognitive bases. Let me first stress that by “cognitive” I do not mean to exclude perceptual states. As the term “cognitive base” is commonly used, it refers to a broad range of representational states, including sensory perceptions. Conceived in this way, it is widely accepted that to fear a tiger, say, you need to first see or hear the tiger, or at least believe that there is a tiger nearby. The idea is that emotions always depend on some prior grasp of things. Now, as Schleifer McCormick notes, this contrasts with the sensory perception of the tiger as dangerous, where there does not appear to be a two-step process. She is right that this makes for a kind of mediation in the emotion case, but contrary to what appears to be the case when the mediation involves a bodily representation, it does not appear counterintuitive to say that you need to have a prior grasp of something in order to fear it and thereby to be aware of its dangerousness.

The last question Schleifer McCormick raises concerns the notion of evaluation. As far as I understand her worry, the problem she sees concerns the lack of objectivity. She notes that when a clock stops working, we can check the time on other clocks, but not so with emotions. She is right, of course, that in the case of emotions, we have no way to independently assess whether the evaluative feature is present. All we have are our emotional reactions plus the ones of other people, and all of these could well be off track. But then, that does not seem to be so different from the clock’s case: there, too, other clocks might be dysfunctional. In any case, the fact that we are limited to emotions (admiration, say) for accessing the corresponding property (being admirable) makes it difficult to be certain that we get things right, but it does not prevent us from collectively working towards a better grasp of the admirable.

Michael Milona notes, in his discussion of chapter 7, that the book is programmatic in its response to the reliability challenge. Let me confess that I remain skeptical about reliabilism. I am more attracted to an evidentialist account of justification, according to which unreliability considerations feature as defeaters. In any case, Milona makes three plausible points about how an epistemology of values based on emotions should be developed. He correctly points out that we need an account of how we come to learn about defeaters for emotions and suggests that one option is to look at meta-emotions, such as the experience of unease when one feels anger. I agree that such an experience might indeed indicate that something is amiss with one’s emotions. But, more generally, I believe that what we know about defeaters comes mainly from comparing our emotional reactions at different times as well as with the emotions felt by other people in similar situations. The discrepancies that emerge from these comparisons help us discover that some conditions, such as lacking information or being tired, interfere with our emotions. The second point Milona makes is that in some cases an emotion can lead to mistakes that have little to do with the content of the emotion. The example he gives is that of disgust leading to harsher judgement of wrongness. This, he holds, does not show that there is something wrong with the claim that emotions justify the beliefs that correspond to the content of the emotion, such as something being disgusting in the case of disgust. I am inclined to agree but I wonder what accounts for such cases. It would seem that the effect of disgust on wrongness judgement needs a different explanation from what might explain a case in which an experience of something as triangular causes the belief that something is greener than it was before the experience of its shape. The last point is that a complete account needs to explain not only the cases in which emotions are in a position to justify evaluative beliefs, but also cases of emotional unreliability. This strikes me as a sensible point.

Let me also say a word about the objection from why-questions. Milona sketches an alternative and promising response to this objection. According to that response, whatever confers justification on emotions falls short of what would be needed to justify the corresponding evaluative belief, in that, in contrast to evaluative beliefs, emotions are justified by states that lack evaluative content. According to this picture, emotions would confer justification to evaluative beliefs provided that they are themselves justified. Suppose you see a bear. This would constitute a good reason to feel fear. Thus, because your fear is justified, the evaluative belief that the bear is dangerous would also be justified. On the suggestion I make in the book, emotions would simply count as justified by default, whether or not they are based on good reasons. The idea is that if you feel fear, the emotion you feel is justified by default, independently of the fact that this emotion is based on a state that constitutes a good or a bad reason for the emotion. It is only if you have reason to think that your emotion is based on a bad reason that the emotion loses its justificatory power. More would need to be said to spell out this suggestion, but the attraction is that it accounts for the intuition that there is something immediate in the justification that emotions confer.

Catherine Rioux, in her commentary on chapter 8, raises the question of whether emotions play a role in weakness of will as distinguished from akratic action. Weakness of will is understood as involving irrational revision of one’s prior resolution. As she suggests, it seems very plausible that emotions, by focussing an agent’s attention on something and by providing prima facie justification for an evaluative belief that is tied to what agents take themselves to have reasons to do, can, in some cases, induce an irrational revision in the face of temptation. It should be noted that, in some cases, acting on the emotion and revising a resolution are of course the rational thing to do. This is for instance the case when the danger of performing some action is just too high to make it in any sense reasonable to act on a resolution. In such a case, the agent’s fear may make for more rationality. Rioux also asks whether emotions could play a role in favouring resoluteness. In principle, it seems quite possible that the emotion of shame can play such a positive role. Out of shame of appearing weak, we might resist reopening the deliberative question. As Rioux states, this is an interesting question for future research.

Jules Salomone-Sehr is focussing on cases of so-called arational actions—that is, cases of expressive actions that appear both intentional and not done for any reason, such as jumping for joy. He argues that in fact, such cases are perfectly rational: they are done for the simple reason that expressing our emotions is good for us, even if we have limited awareness of such a reason. It might well be true that, in some cases, we express an emotion simply because this is good for us. But I doubt that this covers all the cases that are discussed in the literature. Salomone-Sehr may be right that focussing on the case of someone attacking a photograph out of hatred may be too unusual to help understand expressive actions. But there are other cases that also seem puzzling, such as the case of someone who rolls in a deceased person’s clothes out of grief. Even if this action might feel good to the agent, it seems difficult to believe that the value that is tacitly aimed at is that it is good for oneself to express one’s grief. Even if the action in question seems good in a way, it does not seem aimed at our own good. Moreover, invoking the goodness of expressing one’s grief would not explain why the agent is rolling in the deceased person’s clothes rather than putting them into the washing machine, say.

Max Lewis focusses on the account of sentimentalism offered in chapter 9. He argues that the notion of fittingness as it figures in this account is a normative notion, so it cannot be understood as consisting in correct representation. The justification he gives for this claim is that fittingness exhibits the same features as reasons, which are paradigmatic normative entities. Fittingness, he argues, is sometimes permissive, such as when we say that admiring a landscape is fitting. But it can also be requiring, such as when we hold that it is fitting to feel guilt or gratitude or grief in certain circumstances. It is not clear to me that fittingness can be permissive, but for the sake of the argument, let me grant this point. What seems clear is that accepting that fittingness has these features does not exclude the idea that emotions have representational content that can be correct or incorrect. Fittingness would simply be a distinct dimension of assessment, one that can survive along with that of representational correctness. Given this, the version of sentimentalism I spell out would have to be rephrased to say that something is admirable if and only admiration is a representationally correct response to it. Questions regarding the norms of fittingness arise. When is it permissible or required to experience an emotion? What makes it permissible to feel admiration or required to feel grief? Are these norms societal, prudential, moral, or possibly sui generis? In any case, in the absence of an argument to the contrary, the existence of such norms is quite compatible with a representational account of emotions, just as the existence of social, prudential, or moral norms regarding what to believe are compatible with the claim that beliefs are truth-assessable. It might be prudentially required to believe that one will succeed in an examination, but this does not show that beliefs are not truth-assessable.

Mauro Rossi plays the devil’s advocate by raising questions concerning the account of virtue outlined in chapter 10. The question at the heart of that chapter is whether the core of virtue is constituted by emotional dispositions or by evaluative knowledge, as what I call the Socratic interpretation holds. For starters, he offers a reply to the objection from overintellectualization that has been raised against the view that evaluative knowledge is central to virtue. What he suggests is that virtue might involve practical wisdom understood as the ability to use evaluative knowledge without having to deliberate. There are different ways to spell out this suggestion and at least one of them is fully compatible with the idea that emotions constitute the core of virtues. Insofar as virtues have as their core not only single-track emotional dispositions but also multitrack dispositions—that is, sentiments—that consist in caring about, or more generally valuing, things such as truth or welfare, they can be thought to involve tacit knowledge regarding the value of such things, knowledge which can unreflectively be applied to particular situations in which the value of truth or welfare is at stake. The question, which I will leave open here, is which way of spelling out the story is more convincing. Unless we have independent reason to adopt the second way of spelling out the idea, the overintellectualization objection ends with a draw between the Socratic interpretation and the emotion-based account.

Rossi also proposes an argument for the claim that evaluative and indeed moral knowledge are required for virtue. He starts from the observation that exemplars of virtue reliably make correct judgments about what virtue requires. It follows from this that the virtuous agent must possess an emotional trait that it is sensitive to the value that the virtue targets. In the case of honesty, for instance, the value will be truth. According to Gopal Sreenivasan (2020), whose view I explore in chapter 10, this requires having a trait that gives rise not only to representationally correct emotions, but also to morally fitting emotions. In fact, I doubt that the further requirement, concerning the moral fittingness of emotions, is necessary. It can be agreed that an emotion can correctly represents the evaluative property of its intentional object while being morally problematic. A cruel joke can be genuinely amusing, so that amusement would be correct but somewhat heartless. But the question here is whether we should require virtues to give rise to all-things-considered moral verdicts or only to verdicts on what a particular virtue requires. Maybe an exemplar of compassion will be good at making correct judgments only about what compassion requires, so that to be sensitive to injustice, say, that exemplar might need another virtue. But whether emotional dispositions need to be rectified in the restricted sense or in a broader moral sense, Rossi is right to ask how this could happen independently of the agent’s being taught evaluative knowledge. More precisely, he asks how an agent can change their emotions’ calibration files without being provided with the relevant knowledge. As I explain in chapter 12, calibration files can be changed in several ways, including learning by imitation and instructed learning. Instructed learning fits the knowledge model. We would need to be told what merits sympathy in order to learn to be compassionate. However, calibration files can also be changed by observing others’ emotional reactions. In such a way, we might learn, if we are lucky to have good role models, to feel sympathy not only at the distress of one’s dear and near, but also at the distress of strangers, for instance. Even if this can be considered to consist in the acquisition of tacit knowledge, it would place emotions at the core of virtue.[1]

Ronnie de Sousa raises several difficult questions concerning chapters 11 and 12. He starts with remarks concerning emotional regulation. As he points out, emotion regulation need not aim at having emotions that are fitting. He is also right to stress that emotion regulation can be driven by emotion, such as when music elicits an emotion that reduces the impact of another. As he notes, there are further questions here concerning the dynamics of emotions. If Hume is right to think that security is an emotion, how does it interact with fear? There is clearly room for further work here. Furthermore, de Sousa argues that nothing important hangs on the issue whether such emotions felt toward fictions are genuine or not. In part, he might be right: the effect of quasi-emotions, if there are such things, directed at fictions might be indistinguishable from the effect of genuine emotions. I believe there are nonetheless interesting theoretical questions related to this issue. One question, for instance, is whether we need to believe that an intentional object exists for us to experience an emotion towards that object.

The final remarks de Sousa offers concern the notion of flow in relation to listening to music. He doubts that listening to music shares the features of flow, for this activity does not make for a challenge that might match one’s skills, where the activity affords a clear and proximal goal, immediate feedback about progress, and a sense of control or mastery. It is true that it is not obvious that listening to music requires a skill. Because dancing to music is an activity that can obviously occasion flow, I suggested in the book that listening to music can involve a kind of inner dance, amounting to a sequence of body representations that do not translate into motor patterns. However, I think now that it is not so much the bodily movements or their representations that matter as the understanding of the music that is expressed by these movements. The specific challenge, when dancing to music and more generally when listening to music, is to understand its rhythmical, melodic, and harmonic structure, where this understanding is not a matter of articulating musical concepts, but of intuitively grasping the intricacies of the music. This, it seems to me, is clearly an activity that can result in flow.

Laura Silva generously took up the challenge to comment on the political role of emotions. She explores what an account on the lines of the receptive theory entails regarding the political importance of emotions. What Silva argues is that accounts of emotions that take them to have nonconceptual representational contents allows one to understand the political importance of emotions that feminists have been underscoring. It is because emotions involve information that outstrips conceptual abilities that they are often better guides to combatting injustice than our explicit judgments. As she explains, the claim that emotions can justify evaluative beliefs is also one that has political implications, since emotions such as anger will allow agents to have justified beliefs that are politically relevant. As she notes, an internalist account of justification entails that in some cases, the prima facie justification grounded in emotion will be defeated. For instance, agents who believe that their emotions are systematically unreliable will not be justified in trusting their emotions. As a result, their evaluative beliefs will fail to be justified. Similarly, under conditions of oppression, agents are likely to form false beliefs about defeaters. Silva suggests that given this it would be preferable to adopt an externalist perspective. However, one might argue that it would be wiser to acknowledge that oppressive conditions can give rise to epistemic injustice in that they prevent agents whose emotions are accurate from forming justified beliefs. Silva’s final remarks concerns the link between emotions and motivation. She convincingly argues that denying that emotions are constitutively tied to specific action tendencies makes room for a picture of emotions that avoids caricaturing them as involving primitive and objectionable motivations, such as attack or revenge in the case of anger. Overall, Silva’s comments make for a particularly welcome addition to the book, since they address questions that did not find their way into this edition. But who knows about further editions?

Appendices

Note

-

[1]

Thanks to Mauro Rossi for discussions.

Bibliography

- Elster, Jon, Alchemies of the Mind: Rationality and the Emotions, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Rorty, Amélie O., “Explaining Emotions,” in Amélie O. Rorty (ed.), Explaining Emotions, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1978, pp. 127-151.

- Sreenivasan, Gopal, Emotion and Virtue, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2020.