Abstracts

Abstract

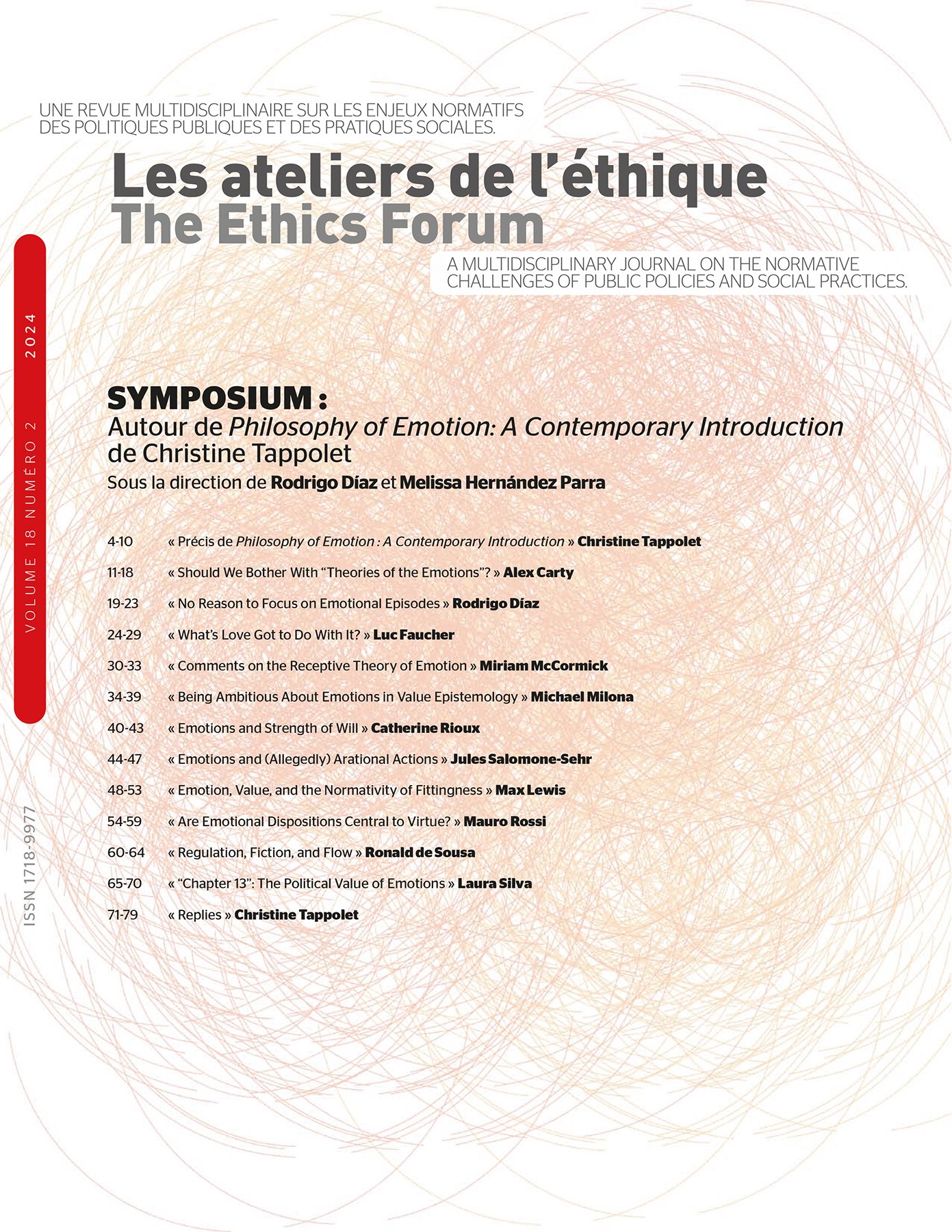

Christine Tappolet had plans to include a thirteenth chapter, on the political value of emotions. As the chapter did not come to fruition, at least not in the current edition, I will here outline what I take to be the main political upshots of Tappolet’s philosophy of emotion.

Résumé

Christine Tappolet avait prévu d’inclure un treizième chapitre sur la valeur politique des émotions. Comme ce chapitre n’a pas vu le jour, du moins pas dans la présente édition, je vais ici exposer ce que je considère être les principales retombées politiques de la philosophie des émotions de Tappolet.

Article body

It is clear from Tappolet’s fantastic introduction that the dominant view of emotions in the contemporary literature is that they are normatively assessable phenomena, that they have fittingness conditions or normative reasons, i.e. that they are in some sense rationally assessable. Although different views diverge regarding the details, it is politically significant that this is the dominant view in the philosophy of emotion. This is because, holding that emotions can be rational in a context where those groups of people that have been historically associated with emotions (i.e., women and racialized groups) are seen as less rational as compared to other, “less emotional” groups (i.e., men and white people), helps improve the status of these minoritized groups. In this sense, philosophy of emotion (whether inadvertently or not) aligns itself with thinking in feminist philosophy that has long condemned the strict reason/emotion dichotomy for its falsity and for its nefarious role in ranking some groups above others (Fricker, 1991; Hall, 2005; Kingston and Ferry, 2008).

Christine Tappolet had plans to include a chapter on the political value of emotions. As this “thirteenth” chapter did not come to fruition, at least not in the current edition, I will here outline what I take to be the main political upshots of Tappolet’s philosophy of emotion. This will be a sketch that will leave many of the details to be filled in, but it will, I hope, be a telling one, nonetheless. The political value of emotions is an emerging area of research in analytic philosophy, such that this short piece can be read as a mapping of key directions this research program might take, while outlining the profound influence Tappolet’s views will undoubtedly have on this emerging subfield. Due to space constraints, I will focus on three of Tappolet’s main tenets and outline their respective potential political upshots. These tenets are (1) her theory of representational content, (2) her epistemic-role thesis, and (3) her view on the practical role of emotions.

1. Representational content

It is a mainstream view in contemporary philosophy of emotion that emotions have intentional content, that they are about things, or involve representations of their objects. Tappolet’s specific view on this pushes an analogy with perception whereby emotions represent objects as having evaluative properties in analogue format, the paradigmatic format of nonconceptual content (Tappolet, 2023, ch. 6). The idea is that emotional experiences involve nonconceptual evaluative representations. Indeed, this is a popular view amongst most perceptual theorists of emotion (see Scarantino and de Sousa, 2021), yet the political potential of such a view is rarely probed. I will have the space only to outline what I have in mind here, but, in short, I consider the fact that emotions likely have nonconceptual representational content to be central to their political potential.

The first reason for this is that when translations are attempted between different representational formats, from nonconceptual to conceptual content in our case, information is, typically, lost (Detske, 1981). This bestows emotions with the epistemic potential of carrying information that outstrips our current concepts (concepts which, under nonideal conditions of structural oppression are likely to be tainted and constrained by existing ideology). In other words, nonconceptual content may allow emotions to, at least sometimes, resist being subsumed under pre-existing concepts and to “break through” conventional concepts and belief systems to provide potentially crucial/novel information. This may help bolster claims in feminist philosophy that emotions are often better guides than our explicit judgements to understanding and combating injustice (Frye, 1983; Jaggar, 1989; Silva, 2021d). Relatedly, this may make emotions key players in conceptual innovation, as, in sharing and articulating first-personal emotional experiences that break through conventional norms, agents may be able to develop new concepts that help designate neglected harms. This is arguably what occurred in the genesis of the concept of sexual harassment through consciousness-raising efforts (Fricker, 1991; MacKinnon, 1979; see Silva, 2022b). Through collective discussions of various forms of anger and discomfort, women came up with a concept under which all relevantly similar offences fell. Lastly, this theory of representational content can, arguably, more readily deliver on the intersectional conviction that the emotional experiences of differently situated agents, even if directed at the same object and representing the same evaluative property, are not entirely the same (the anger of a black women against structural racism is different from that of a white male ally). Tappolet’s theory of representational content can account for such differences at the nonconceptual experiential level, without denying the conceptual representational content shared across differently situated agents.

It is important to note that holding that emotions involve nonconceptual representations may not come without its weaknesses at the political level. Tappolet’s view of the representational content of emotions will, however, I think be particularly well placed to help diagnose these weaknesses, which include the underappreciated prevalence of affective experiences at play in standard cases of epistemic injustices, as well a range of distinctively affective injustices (Pismenny et al., 2024; Gallegos, 2021; see Silva, 2022b).

2. Epistemic role

Tappolet is a renowned advocate of the justification thesis, which grants emotions strong epistemic roles. The justification thesis holds that emotions provide immediate prima facie justification for evaluative beliefs with similar content. This thesis delivers on the important role that feminist thinkers and activists have pushed in programmatic terms for years: that emotions are rational basis for belief (Fricker, 1991; Frye, 1983; Hall, 2005; Jaggar, 1989).

Tappolet’s justification thesis spells this out in concrete terms and helps explain how emotions can often justify important evaluative beliefs in contexts of oppression. Given the scope of internalized oppressive beliefs in such contexts, not requiring further beliefs or justificatory steps between the emotion and the justification of an evaluative belief is an important, and arguably radical, claim. Even in cases where agents don’t understand their own emotions and may lack independent reasons to think these are valid, one’s emotions are still apt to provide justification for evaluative beliefs that would otherwise likely have lacked justification. A clear example is that of outlaw emotions, such as anger at sexual harassment in a context where this concept is lacking and where one believes the actions against oneself to be “a compliment” (Jaggar, 1989; Silva, 2021d). The justification thesis holds that outlaw anger in such a case can provide justification for an evaluative belief of the sort “what happened was not okay,” despite going against the agent’s wider belief system.

There is a worry here regarding whether and how the outlaw emotion of anger can provide ultima facie justification to the relevant evaluative belief given that a multitude of defeaters abound (and the justification thesis guarantees only prima facie justification). In chapter 7, Tappolet adopts an internalist picture of justification that may not be the best suited to respond to this worry. Tappolet’s picture is evidentialist, where reliability concerns take the form of potential defeaters within an evidentialist account. That is, the justification emotions provide beliefs is by way of being experiences that count as evidence in favour of relevant beliefs. And if one has reason to believe that one’s emotion is unreliable, then this defeats the justification of the relevant belief. Such a picture runs into problems in nonidealized cases that preoccupy feminist philosophers, for two main reasons:

Omnipresent defeaters: Under certain oppressive ideologies, emotions are seen as unreliable, unacceptable bases for beliefs, such that we might find the justification of our emotion-based beliefs systematically defeated.

Tainted evidence: Under conditions of oppression, bad evidence will abound. An internalist account is arguably harder pressed to account for this as how things stand from the agent’s perspective is central. An externalist account, on the other hand, may be better placed to deliver the verdict that the agent’s belief-forming mechanisms are unreliable under such oppressive conditions (Silva, 2021d; Srinivasan, 2020).[1]

That being said, the jury is still out on how to best respond to these worries and on whether an internalist or externalist reply will be most satisfactory. Either way, it seems likely that some version of the justification thesis will survive and live on to support and explain the strong epistemic role of emotions under conditions of oppression.

3. Practical role

On motivational views, which are gaining popularity and rival Tappolet’s account (Tappolet, 2023, ch. 5), emotions constitutively involve specific action tendencies that at least partly individuate emotion types. In the case of anger, for example, the constitutive action tendencies are taken to be tendencies to attack or retaliate (Deonna & Teroni, 2015; Tappolet, 2023). On Tappolet’s view, emotions do not constitutively involve specific desires nor precise action tendencies. This allows Tappolet’s view to better account for emotions that do not have clear conative components or behavioural manifestations, such as joy, nostalgia, and awe, but it may also set the stage for emotions to be afforded more flexibility and context dependency. This is particularly important in the case of anger, the paradigmatic response to injustice, which I will use as an example case throughout this section.

I have argued that empirical work supports a view of anger as involving different action tendencies depending on the context/situation (Silva, 2021a; 2021c; 2021b). This also fits better with recent work in feminist moral psychology that highlights the recognitional aims of anger (to have an injustice acknowledged) and aims for rectification, rather than retribution/punition as central to anger (Cherry, 2021; Lepoutre, 2018; Srinivasan, 2020; Silva, 2021a). This has consequences for the moral status of anger, for its political acceptability, and for its efficacy (Silva, 2021a; 2021c).

Motivational theorists seem to think their view has evolutionary evidence and scientific plausibility on their side as “ancient” or “primitive” anger is considered uncontroversially attack oriented (Deonna & Teroni, 2012, ch. 7; Scarantino and de Sousa, 2021). The latter point has been questioned (see Silva, 2021b), while the former point could be replaced by an alternative story that I believe garners more empirical support (Silva, 2021b; 2021c). Anger’s ancient affect-program ancestor likely involved attack behaviour, but a non-attack-oriented anger was likely evolutionarily beneficial to humans long before today (Silva, 2021b; Sterelny, 2006). Anger may have evolved to have other, pluralistic, functions, which reflect our social evolutionary past, as opposed to being attack oriented at its core and having these tendencies repressed through our upbringing and modern culture.[2]

Indeed, I have argued that seeing anger as inherently tied to retribution/punition perpetuates and entrenches oppression as it licences the dismissal of apt anger, which can in turn make anger more retributive, as when anger is systematically denied uptake it will become more aggressive given that agents have exhausted all other options and may have nothing to lose (Silva, 2021b).

By not linking emotions to specific action tendencies or goals, Tappolet’s view may afford emotions crucial political roles. In the case of anger in particular, Tappolet’s view sets the stage for the emotion to be rehabilitated and its political potential secured. Tappolet’s view on the practical role of emotions seems to allow the context in which they occur to be taken more seriously than competing views, preventing the “essentializing” of emotions and the perpetuation of potentially biased views of what emotions aim for and are all about.[3]

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Similar claims for practical rationality could perhaps be made (Silva, 2022a).

-

[2]

Note that if motivational theorists insist that anger always involves an attack action tendency, but that this tendency is just regulated/controlled depending on the context, this becomes, at its extreme, an unfalsifiable view.

-

[3]

Whether modified/more recent motivational views can deliver similar results, however, is an open question that has not received sufficient attention.

Bibliography

- Brady, Michael S., Emotional Insight: The Epistemic Role of Emotional Experience, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Cherry, Myisha, The Case for Rage: Why Anger Is Essential to Anti-Racist Struggle, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Deonna, Julien and Fabrice Teroni, The Emotions: A Philosophical Introduction, London, Routledge, 2012.

- Deonna, Julien and Fabrice Teroni, “Emotions as Attitudes,” Dialectica, vol. 69, no. 3, 2015, pp. 293-311.

- Dretske, Fred, Knowledge and the Flow of Information, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1981.

- Fricker, Miranda, “Reason and Emotion,” Radical Philosophy, no. 57, 1991, pp. 14-19.

- Frye, Marilyn, The Politics of Reality, Trumansburg, Crossing Press, 1983.

- Gallegos, Francisco, “Affective Injustice and Fundamental Affective Goods,” Journal of Social Philosophy, vol. 53, no. 2, 2021, pp. 185-201.

- Hall, Cheryl, The Trouble with Passion: Political Theory beyond the Reign of Reason, New York, Routledge, 2005.

- Jaggar, Alison M., “Love and Knowledge: Emotion in Feminist Epistemology,” Inquiry, vol. 32, no. 2, 1989, pp. 151-176.

- Kingston, Rebecca and Leonard Ferry (eds.), Bringing the Passions Back In: The Emotions in Political Philosophy, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 2008.

- Lepoutre, Maxime, “Rage Inside the Machine: Defending the Place of Anger in Democratic Speech,” Politics, Philosophy and Economics, vol. 17, no. 4, 2018, pp. 398-426.

- MacKinnon, Catharine A., Sexual Harassment of Working Women, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1979.

- Mitchell, Jonathan, “Affective Representation and Affective Attitudes,” Synthese, vol. 198, 2021, pp. 3519-3546.

- Pismenny, Arina, Gen Eickers, and Jesse Prinz, “Emotional Injustice,” Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy, vol. 11, no. 6, 2024, pp. 150-176.

- Scarantino, Andrea and Ronald de Sousa, “Emotion,” in Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2021. URL: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/emotion/

- Silva, Laura, “Anger and Its Desires,” European Journal of Philosophy, vol. 29, no. 4, 2021a, pp. 1115-1135.

- Silva, Laura, “Is Anger a Hostile Emotion?,” Review of Philosophy and Psychology, vol. 15, 2021b, pp. 383-402.

- Silva, Laura, “The Efficacy of Anger: Recognition and Retribution,” in Ana Falcato and Sara Graça da Silva (eds.), The Politics of Emotional Shockwaves, Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021c, pp. 27-55.

- Silva, Laura, “The Epistemic Role of Outlaw Emotions,” Ergo, vol. 7, no. 23, 2021d, pp. 664-691.

- Silva, Laura, “Emotions and Their Reasons,” Inquiry, vol. 68, no. 1, 2022a, pp. 47-70.

- Silva, Laura, “The Ineffable as Radical,” in Christine Tappolet, Julien Deonna and Fabrice Teroni (eds.), A Tribute to Ronald de Sousa, 2022b. URL: https://sites.cisa-unige.ch/ronald-de-sousa/assets/pdf/Silva_Paper.pdf

- Srinivasan, Amia, “Radical Externalism,” The Philosophical Review, vol. 129, no. 3, 2020, pp. 395-431.

- Sterelny, Kim, “The Evolution and Evolvability of Culture,” Mind & Language, vol. 21, no. 2, 2006, pp. 137-165.

- Tappolet, Christine, Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, New York, Routledge, 2023.