Abstracts

Abstract

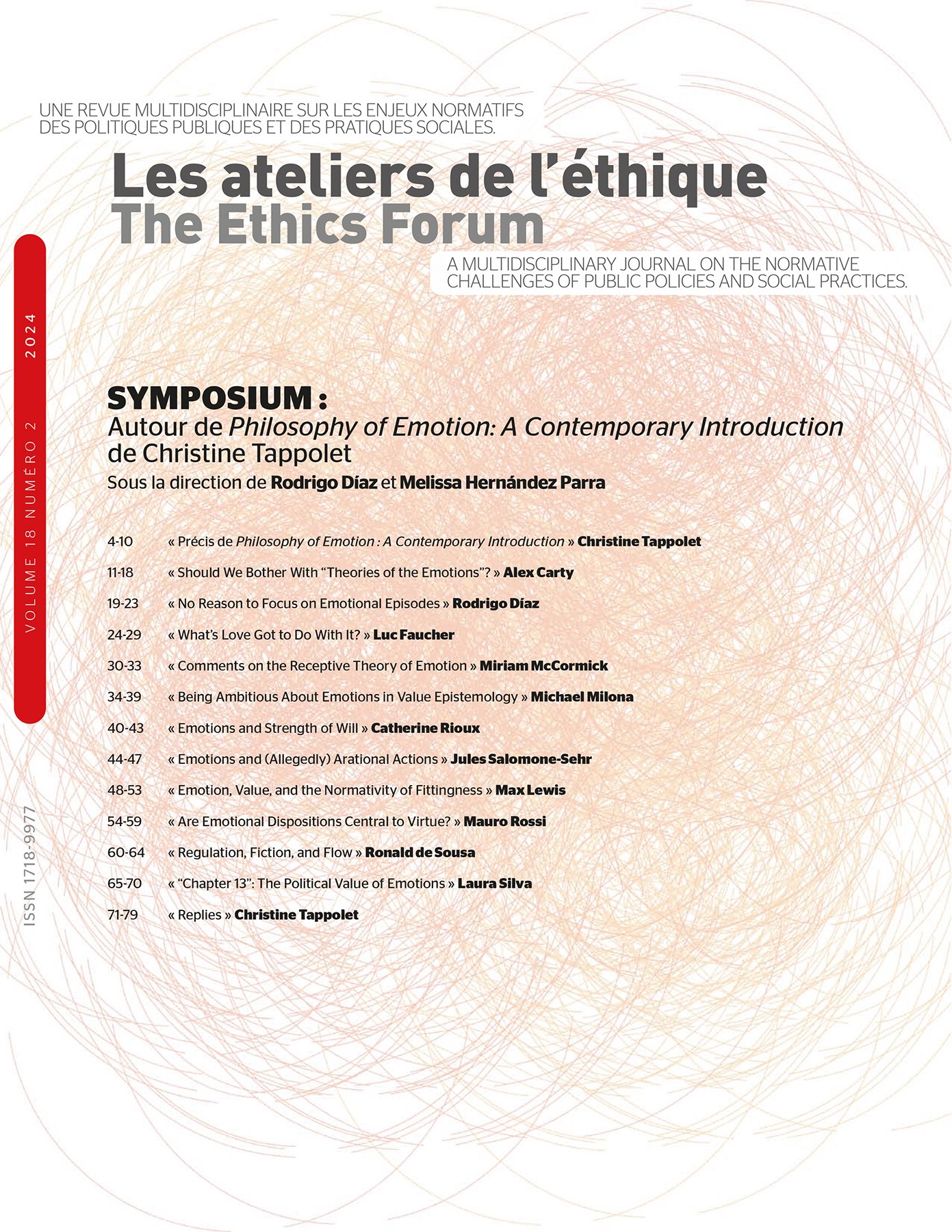

Chapter 11 contains two primary topics, the regulation of emotions and questions arising from the power of music to arouse, express, or represent emotions. After some brief remarks about emotion regulation and a speculative thought about emotions in response to fiction, I raise some doubts about the discussion of “flow” in connection with listening to as opposed to performing music.

Résumé

Le chapitre 11 porte principalement sur deux sujets: la régulation des émotions, et le pouvoir qu’a la musique de les susciter, de les exprimer et de les représenter. Après quelques brèves observations sur la régulation d’une émotion par une autre, je passe à certaines conjectures à propos des émotions évoquées par la fiction. Enfin je soulève quelques doutes quant à la pertinence du concept de ‘flow’ à l’écoute plutôt qu’à l’exécution d’une performance musicale.

Article body

Chapter 11 contains two primary topics, the regulation of emotions and questions arising from the mysterious power of music to arouse, express, or represent emotions.

1. How emotional is emotional regulation?

At the end of chapter 9, Tappolet writes that “the question that appears most urgent is how we could set about having emotions that are fitting” (p. 188). I begin by raising the question of the goal of emotional regulation. I think we all agree that fittingness is only one kind of appropriateness of emotion. I can certainly see that one goal or regulation might be to make it more fitting. I’m thinking of a case where I feel that my response to some event is just not adequate. Sometimes, I feel I should care more than I do. Perhaps sad music could help me concentrate on the sadness of a situation to which I am responding in this embarrassingly insensitive way. In many other cases, however, one wants to tamp down an emotion not because it is not fitting, but because experiencing it is pointlessly unpleasant. Anger, for example, might be perfectly fitting in the case of someone who has gratuitously offended me; but I might much prefer to cease caring at all. Or, on the contrary, I might want to get even angrier than is fitting, in the hope of getting some compensation for the offence.

My wish to manipulate my own emotion might itself be driven by emotion. Most techniques of emotional self-regulation, however, are not themselves emotional. They are either simply practical, like changing the setting, or purely cognitive, like reappraisal, which is probably the most powerful when it can be achieved (Gross 2010). So, music is especially interesting in that it works by eliciting an emotion that directly reduces the impact of another emotion. This raises a further question about when two emotions are dynamic opponents, in the sense that one must diminish insofar as the other intensifies. Tappolet describes '“security” as “the opposite of fear” (p. 9). But what is it for two emotions to be “opposites”? Does it mean their formal objects are inconsistent? or that they are incompatible—that is, cannot be felt at the same time? Some pairs of emotions generally inhibit one another, yet sometimes have the opposite effect. Lust and disgust are notorious examples: incompatible in most circumstances, yet sometimes mutually reinforcing.

2. Should we worry about genuineness?

Tappolet writes on p. 193: “A good question here is how it is possible that works of art, and more specifically works of fiction, can cause emotions.” I’d like to hazard a suggestion. There is some evidence that, psychologically, knowledge is prior to belief (Phillips et al., 2021). It takes a sophisticated “theory of mind” for a child to notice the potential gap between ascribing a factive attitude and ascribing a belief (Nagel, 2017). If so, it makes sense to think that when we hear a story, the default emotional mode automatically adopted is knowledge, rather than belief (plus justification nonaccidental causation, or whatever latest Gettier-guard is in fashion). That might explain why you respond emotionally to fiction as to factual information: just as our emotions often outlast their objects, so perhaps an emotional attitude aroused by a story may remain even after the realization that the story isn’t true.

But if the situation isn’t real, is the emotion real? I confess I can’t get very interested in this question. As Agnes Moors has recently argued, emotional taxonomy has been a huge industry, and it’s not obvious that all the different proposals are really competitors rather than alternative styles of emphasis (Moors, 2022). In the case of fear at a horror movie scene, for example, is the question whether I am really (or at all) motivated to run away? Well, I might be, but as I know I am at the movies, I could want to run away because the movie is boring or disgusting and not in the least frightening. So, I might need another test for genuineness. But again, the question of genuineness is of interest only to someone who thinks each emotion has an essence that differentiates it from every other. If we think of emotions in the spirit of Batja Mesquita (2022), as tied to the social practices in which they acquire their significance, every episode is located in a vast space of possible emotions, and at indefinitely variable distance from every other. On such a picture, it seems idle to ask whether one is really the same as another or just closely akin to it. Tappolet’s book does a marvellous job of showing how important emotions and more broadly affective phenomena are to our lives, but I don’t see that anything important hangs on the issue of what is or is not a genuine emotion, or on the related question of when two emotions (fear of the real tiger, fear of the tiger in the movie) are or are not the same emotion.

3. How does the appeal to flow illuminate music’s contribution to our well-being?

Tappolet makes much of the capacity of music to generate flow, in the sense characterized by Csikszentmihalyi (1990). She writes:

Interestingly, if it is true that listening to music can induce flow experiences and flow is a kind of enjoyment, we can see why music is one of the main sources of happiness. If listening to music is liable to cause this kind of enjoyment, we have a good explanation of why listening to music makes us happy.

p. 222

One thing that links music to emotion is that both are universal among humans, yet highly individual in practice. Although tastes in music differ widely, nearly everyone has some taste for music. (I know of two famous philosophers who claimed to have no ear for music: Freddy Ayer, who told me so himself, and Gilbert Ryle, who, according to Dan Dennett, said he recognized only two tunes: “Rule Britannia” and “God Save the Queen.” But as he was not able to tell them apart, he would stand up for either (Dennett, 2023).) Nevertheless, here alone in this chapter I am tempted to resist the idea that flow is the reason why music makes us happy.

First, insofar as we listen to music “simply … because we want to achieve the simple goal of improving how we feel” (p. 205), that would apply to anything we enjoy doing. So, the fact that we enjoy music is enough to explain why we want to listen to it, even when “flow” doesn’t apply. The enjoyment of listening to music doesn’t require flow, and its possibility doesn’t pinpoint any unique characteristic of music as opposed to other human interests or activities. As Tappolet points out right before the passages just quoted, “[t]he activities which can induce flow are quite varied and include rock climbing, sailing, chess, video games, dancing, painting, sculpting, composing, and writing” (p. 205). The list is highly subjective: as she points out, Csikszentmihalyi specifies that a crucial necessary condition for flow is that the activity present “a challenge that matches your ability” (p. 205). But we can enjoy music in lazier, more passive ways than the other activities listed.

The point about flow undoubtedly does apply to performance, where the key elements of challenge, feedback, a “sense of control and mastery” (p. 206) and so on are clearly present. Musical performance, whether instrumental or vocal, solo or ensemble, presents an ideal situation in which flow can be achieved. But those who, like me, are not themselves musicians wouldn’t know how to apply the second crucial criterion of “[c]lear proximal goals and immediate feedback about progress” (p. 205). When one attempts to listen actively to music, it isn’t clear what success or failure consists in or what the feedback amounts to. Neither is it obvious what could be meant, as concerns listening rather than performance, by a “sense of mastery” (p. 206). The association of flow with listening to music isn’t frequent or clear enough to explain the enjoyment we derive from it.

Lastly, while I certainly agree that “flow is directly opposed to anxiety and boredom” (p. 205), I am not convinced that “flow itself is also an emotion” (p. 206). Although Tappolet argues that flow has a formal object, it doesn’t seem to have correctness conditions. Or rather, perhaps, it is just guaranteed to be correct: flow might be to emotion what a factive state is to a doxastic one: a state that, by definition, has already achieved its correctness conditions.

4. Conclusion

Let me end by expressing my admiration for Tappolet’s book as a whole and for this chapter in particular. I’ve done my utmost to find something to disagree with, but it wasn’t easy. For the chapter does a truly masterly job of compressing pretty much everything worth thinking about on these topics. Most of it had me nodding in enthusiastic assent or discovery. I’m sure that, as she wrote it, Tappolet must have enjoyed a fine state of flow.

Appendices

Bibliography

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, New York, Harper and Row, 1990.

- Dennett, Daniel C., I’ve Been Thinking, New York, W.W. Norton, 2023.

- Gross, James J., “Emotion Regulation,” in Michael Lewis, Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones and Lisa Feldman Barrett (eds.), Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed., New York, The Guilford Press, 2008, pp. 497-512.

- Gross, James J., “Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects,” Psychological Inquiry, vol. 26, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-26.

- Mesquita, Batja, The Space between Us: How Cultures Create Emotion, New York, Norton, 2022.

- Moors, Agnes, Demystifying Emotions: A Typology of Theories in Psychology and Philosophy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Nagel, Jennifer, “Factive and Non-Factive Mental State Attribution,” Mind & Language, vol. 32, no. 2, 2017, pp. 525-544.

- Phillips, Jonathan, Wesley Buckwalter, Fiery Cushman, Ori Friedman, Alia Martin, John Turri, Laurie Santos and Joshua Knobe, “Knowledge Before Belief,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol. 44, art. 140, 2021, pp. 1-75.

- Tappolet, Christine, Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, New York, Routledge, 2023.