Abstracts

Abstract

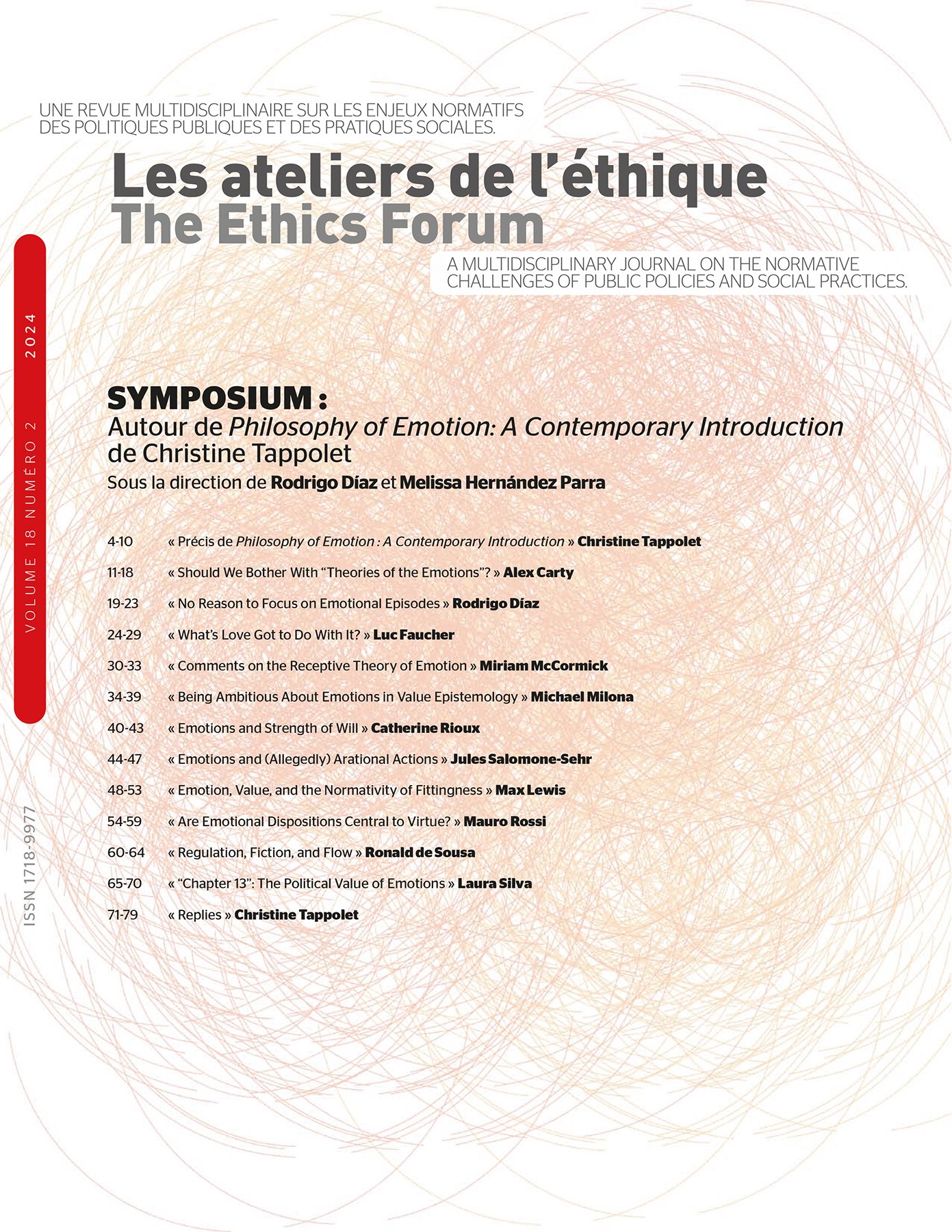

In this article, I offer some comments on chapter 10 of Christine Tappolet’s book Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, the chapter entitled “Ethics and the Emotions”. After presenting the main theses that Tappolet defends in this chapter, I consider some possible replies that her opponents might offer.

Résumé

Dans cet article, je propose quelques commentaires sur le chapitre 10 du livre de Christine Tappolet intitulé « Ethics and the Emotions ». Après avoir présenté les principales thèses défendues par Tappolet dans ce chapitre, je considère quelques réponses possibles que ses adversaires pourraient apporter.

Article body

In this article, I offer some comments on chapter 10 of Christine Tappolet’s book Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, the chapter entitled “Ethics and the Emotions.” The structure of the commentary is as follows. I first present the main theses that Tappolet defends in this chapter and then offer a possible reply on behalf of her opponents.

Tappolet considers the role of emotions in (ethical) virtue (p. 172). She adopts the standard Aristotelian account of virtues as character traits that merit praise. More specifically, on the standard account that Tappolet follows, virtues consist in multi-track dispositions: they involve the disposition to reliably do what is right for the right reasons, but also other cognitive, motivational, and—crucially—emotional dispositions.

The question that interests Tappolet is whether emotions and emotional dispositions are central to virtues or merely peripheral. To address this question, Tappolet examines two models. One is a model on which evaluative knowledge and the disposition to respond to such knowledge lie at the core of virtue. Tappolet calls this the Socratic model. The other is a model on which emotions and emotional dispositions are what is central to virtue. Tappolet presents this model by reference to Gopal Sreenivasan’s (2020) theory, which she amends in some respects but accepts for the most part.

Let me present these models in more detail. Consider an exemplar of virtue—that is, a virtuous agent. An exemplar of virtue reliably does the right thing for the right reasons. To be able to do that, the exemplar must reliably make correct moral judgments of what virtue requires them to do in the circumstances. For Sreenivasan, this step is so important that he calls it the “central test of virtue.” How can an exemplar of virtue reliably make correct judgments of this sort?

Generally speaking, to make correct judgments, the exemplar must identify two things. First, they must identify the values that are relevant in the circumstances. They must be able to do that because requirements of virtue are grounded in values. For example, requirements of compassion are grounded in the good to which compassion is responsive, which is the welfare of the individual in need. So, to act as compassion requires, the exemplar must be able to recognize that there is an individual in need and that this matters in the circumstances. Second, the exemplar must be able to identify the particular response that such values demand in the circumstances. For example, in a situation that calls for compassion, the exemplar must identify the particular way to help the individual in need. So, the question for both models is the following: How can an exemplar of virtue reliably satisfy these two conditions (identify the relevant values and identify the specific response that those values demand), so as to reliably make correct judgments about what virtue requires them to do?

Here is where the two models differ. On the Socratic model, all that the exemplar needs is (roughly) evaluative knowledge and practical wisdom. Evaluative knowledge is required to know which things are good and, thus, worth protecting or promoting. Practical wisdom is required to connect this knowledge to the specific circumstances in which the exemplar finds themselves, and to identify the correct practical response in those circumstances. On this model, emotional dispositions do not play an especially significant role.

Things are completely different on Sreenivasan’s model. According to him, the possession of specific (morally rectified) emotional traits is indispensable for an exemplar of virtue to reliably make correct moral judgments of what virtue requires. (Morally rectified) emotional traits enable the exemplar to accomplish the tasks that are necessary to reliably make correct moral judgments in particular circumstances, namely: (i) recognizing that certain items possess the particular kind of value that virtues target; (iia) recognizing the kind of response that this value requires—that is, the goal that the exemplar ought to pursue; and (iib) identifying the means to achieve this goal. Two other things are required for the exemplar to be a reliable judge—namely, cleverness and supplementary moral knowledge—but for reasons of space I will not discuss them here. According to this picture, the disposition to experience certain emotions is central to virtue, for it is this disposition—and not the disposition to respond to evaluative knowledge—that allows the exemplar to reliably do the right thing for the right reasons.

Tappolet accepts this picture with one important amendment. On Sreenivasan’s view, the emotional traits that are central to virtues are single-track emotional dispositions: they are dispositions to experience instances of a single emotion type. For Tappolet, instead, the emotional traits that are central to virtues are multi-track emotional dispositions—that is, dispositions to experience tokens of a variety of emotion types. Tappolet refers to these multi-track emotional dispositions as “carings,” although it would probably be preferable to call them “sentiments.” This amendment is important, according to Tappolet, because it allows us to capture the widespread idea that virtue involves a variety of affective dispositions.

In what follows, I will try to play devil’s advocate. I want to consider how the defender of the Socratic model could reply to Tappolet. It seems to me that they would proceed in two steps. First, they would try to reject the objections that Tappolet raises against their model. Second, they would argue that in any case the model that Tappolet endorses requires evaluative knowledge.

Tappolet raises two objections against the Socratic model. The first is a revised version of the “objection from modesty” originally proposed by Julia Driver (2001). The second objection is the “objection from over-intellectualization.” For reasons of space, I will discuss only the latter. Tappolet presents it as follows: “. . . virtuous agents are not typically moved by explicit thought concerning the value of what they do. Virtuous agents simply appear to see situations as requiring action, independently of any deliberation about what to do . . . There is thus good reason to doubt that virtuous actions require evaluative knowledge” (pp. 177-178). Tappolet considers the reply to this objection offered by Julia Annas (2011) on behalf of the Socratic model. According to Annas, we should think of virtues as practical skills, akin to other practical skills such as playing the piano. Consequently, we should think of the role of evaluative knowledge in virtue as analogous to the role of knowledge in other practical skills. According to Annas, we need knowledge to learn the relevant practical skills. And because knowledge is involved in learning, the skilled person can and will refer to this knowledge to explain how they are able to exercise their skills. The same basically applies to virtue. Against this position, Tappolet objects that the knowledge required to learn a practical skill is primarily knowledge how, not the kind of propositional knowledge that a defender of a Socratic model deems central to virtue.

I think Tappolet is right about this. But I also think that there is another way for the defender of the Socratic model to go around the objection from over-intellectualization. The first thing they can do is to deny that, just because the virtuous agent does not typically deliberate about what to do, virtuous action does not require evaluative knowledge. It is indeed possible that virtue involves precisely the ability to make use of evaluative knowledge without deliberation. In fact, this may be the (or at least one) sense in which virtues are skills. For the defender of the Socratic model, the element of virtue that allows the virtuous agent to select the relevant evaluative knowledge without reflecting or deliberating is practical wisdom. So, here we have an account of virtue that places evaluative knowledge and practical wisdom at its core, but which is not vulnerable to the objection from over-intellectualization.

The next—and more important—step for the defender of the Socratic model is to argue that, in any case, the model to which Tappolet herself adheres requires evaluative knowledge.[1] To see why, let us go back to Sreenivasan’s theory. As we have seen, in order to reliably make correct moral judgments about what a particular virtue requires, the exemplar of virtue must possess an emotional trait that is sensitive to the same value that this virtue targets. But this is not enough. Crucially, the emotional trait must be morally rectified. Emotional traits are indeed vulnerable to various errors. Moral rectification is necessary to avoid these errors and thereby to maintain reliability in judgment. The question is what moral rectification exactly involves.

Sreenivasan claims that emotional traits “can be morally rectified by adding or subtracting suitable eliciting conditions” (2020, p. 155). Tappolet interprets this as the process ensuring that emotional traits are fitting tout court. I don’t think that Sreenivasan means just that. For an emotional trait can be fitting tout court without being morally fitting. And what we need for virtue is morally fitting emotional traits. So, it seems that we need to do something more than to adjust emotional traits so that they are fitting tout court.

How exactly can emotional traits be morally rectified? Sreenivasan’s idea is that we need to add and subtract eliciting conditions to the emotion’s calibration file. This is suggestive, but not fully informative. We still need to explain both how this addition is done and how it causes the agent to undergo an emotion that makes sense for them to undergo. Here, the defender of the Socratic model has a ready-made explanation. The changes in the calibration file are made by providing the agent with evaluative knowledge. It is because of that knowledge that the virtuous agent will respond with morally fitting emotions in particular circumstances. Moreover, it is the fact that the agent has this evaluative knowledge that rationalizes their emotional responses.

This suggestion puts evaluative knowledge back in the centre. It is, however, still compatible with the thesis that emotional traits play an important role. But the defender of the Socratic model might be tempted to go further. We still need to determine what kind of knowledge the exemplar must be endowed with. There are two options. One consists in holding that the virtuous agent must be endowed with general knowledge—for example, in the form of general principles about the kinds of things that are morally offensive. The other option is to say that they must be endowed with specific moral knowledge—for example, knowledge about which particular items are morally offensive, and which are not.

Both options present some problems for the thesis that emotional traits are central. In the first case, in order for the virtuous agent to be able to correctly respond with a given emotion to a particular situation, they must recognize that the particular situation they are in falls under the scope of the general principles that they are endowed with. The defender of the Socratic model may argue that emotions cannot perform this recognitional task alone, since they are not naturally “attuned” to specifically moral values. To accomplish this task, the virtuous agent needs practical wisdom.

The second option is even worse. If the virtuous agent is endowed with specific moral knowledge, then they have everything they need to recognize which items possess the relevant moral values in specific circumstances. Emotions do not reveal anything new to them. Of course, the agent will still need a mechanism to sort the relevant knowledge out in specific circumstances. Perhaps emotional traits perform this sort of function. But perhaps practical wisdom can accomplish this task as well.

Be that as it may, the defender of the Socratic model will argue that evaluative (and, more specifically, moral) knowledge is required. The only question is whether practical wisdom is sufficient to sort this knowledge out or whether we need emotional traits. Put differently, the real opposition does not concern the role of sentiments versus evaluative knowledge in making correct moral judgments. Rather, it concerns the role of sentiments versus practical wisdom in making use of evaluative knowledge.

Appendices

Note

-

[1]

The argument developed below is based on Rossi (2024).

Bibliography

- Annas, Julia, Intelligent Virtue, New York, Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Driver, Julia, Uneasy Virtue, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Rossi, Mauro, “‘Emotions’ in Gopal Sreenivasan’s Emotion and Virtue,” Analytic Philosophy, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/phib.12342

- Sreenivasan, Gopal, Emotion and Virtue, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2020.

- Tappolet, Christine, Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, New York, Routledge, 2023.