Abstracts

Abstract

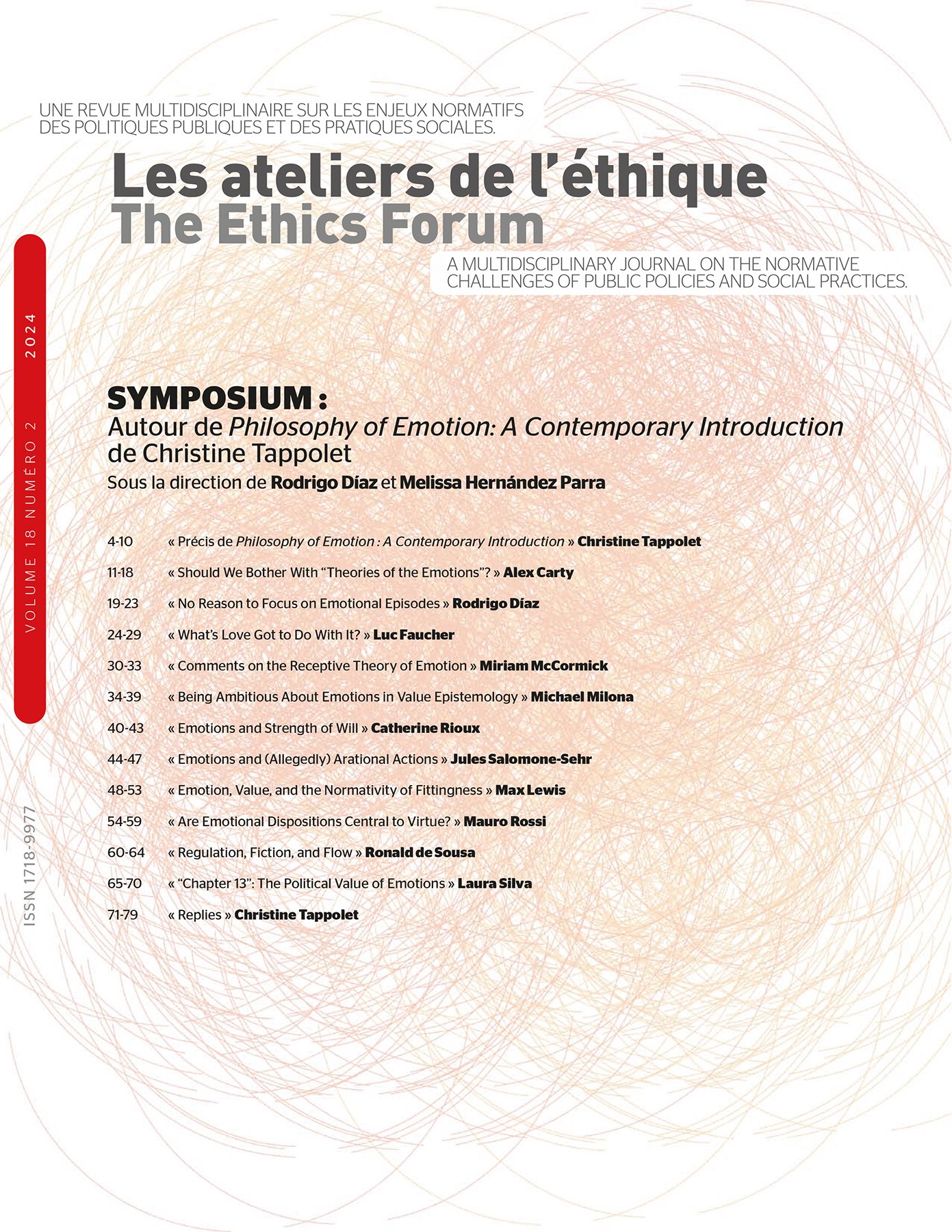

These comments focus on chapter 6 of Christine Tappolet’s Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, asking some questions about her preferred theory, what she calls the “receptive theory of emotions,” and pointing to some areas that could benefit from further clarification.

Résumé

Ces commentaires se concentrent sur le chapitre 6 de Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction de Christine Tappolet, posant quelques questions sur sa théorie privilégiée, ce qu’elle appelle la « théorie réceptive des émotions », et soulignant certains aspects qui pourraient bénéficier d’une clarification supplémentaire.l’homme.

Article body

Chapter 6 introduces Tappolet’s preferred approach in the theoretical terrain—namely, a perceptualist one—and by the end she introduces her latest version of it, what she calls a “receptive theory,” summarized like this: “emotions consist in analog representations, which have evaluative contents that are nonconceptual” (Tappolet, 2023, p. 112). Before arriving there, she surveys evaluative theories more generally, starting with ones that see evaluations as causally connected to emotions. Not too much time is devoted to these since, as she points out, such a view is compatible with all the philosophical theories on offer. She then turns to those that see evaluations as constituents of emotions. She considers judgmentalist and neo-judgmentalist theories, which view emotions as evaluative judgments, before devoting most of the chapter to perceptual theories, which view emotions as, at least, very analogous to sensory perceptions. She canvasses both literal and nonliteral versions, as well as direct and indirect ones. According to the former, emotions are direct perceptual (or quasi-perceptual) representations of evaluative features while for the latter the representation of evaluative features is mediated by some other type of representation. Tappolet pretty quickly dismisses indirect accounts; it seems there are not many options on the table and Prinz’s version has been criticized on many grounds.

A big problem with judgmentalist theories is that they do not do a good job of addressing recalcitrant emotions—namely, emotions that conflict with one’s evaluative judgments. I judge that spiders are not dangerous, but still feel fear when I see a spider. The judgmentalist would claim that the kind of irrationality here is simply one of incoherence, that of having two contradictory beliefs that one recognizes as contradictory: Spiders are dangerous and Spiders are not dangerous. Such a view imputes excessive irrationality to the subject of emotional recalcitrance. Recalcitrant emotions are common and intelligible. And for neo-judgmentalists, who view the evaluations as something less than full-fledged judgments (for example, as construals), there seems to be no irrationality at all; it would be just like believing something and imagining it to be otherwise. As Grzankowski puts the problem:

One must not understand emotions in such a way as to land in incoherence or contradiction, but one must also find room for the sense in which cases of recalcitrance present inconsistency. Theorists about the emotions must find ‘conflict without contradiction,’ and this looks to be no easy task.

Grzankowski 2020, p. 3

Here perceptual theories seem to do better, as we know we can have perceptions that conflict with our judgments. In the Müller-Lyon illusion, you see the lines as being different lengths although you know they are not. When you look at an oar in water, you see it as bent when you know it is straight. So, we have conflict, but where is the irrationality or inconsistency? Tappolet would say that the plasticity of emotional dispositions means we can change them, and so we can be criticized for not having our emotions line up with reality. Indeed, this is one of the disanalogies pointed to between perceptual and emotional experience. But I still think more needs to be said to explain why the tension felt in the case of emotional recalcitrance between one’s feelings and one’s considered judgments differs so much from that in the case of perceptual illusions. In the latter case, one recognizes it is an illusion, and that is the end of the story. I will return to the question of the target to evaluation in a moment.

After enumerating all the virtues of perceptualist theories, Tappolet considers some potential problems. She considers the receptive theory to be a better version because it can overcome these problems. Indeed, it is designed to do so:

The receptive theory is tailored to account for several important differences between emotions and sensory perceptions. Because emotions are thought to be removed from the sensory periphery, the account has no worries regarding the absence of corresponding organs, the dependence on cognitive bases, as well as the fact that emotions need not be causally correlated with their objects.

Tappolet, 2023, p. 111

I will say a little more about these problems and how this theory addresses them.

One issue concerns the kinds of representations that can be nonconceptual, given that babies and nonhuman animals have emotions. She first introduces the problem when considering criticisms of judgmentalist accounts:

The problem, now, is that it clearly seems possible to experience emotions without possessing much in terms of concepts. Consider infants and nonhuman animals. Because infants and nonhuman animals lack linguistic abilities, which are usually taken to correlate with the possession of concepts, there are reasons to think that infants and nonhuman animals lack the ability to make judgments or quasi-judgments… But as the marmot’s fear of the eagle or the feat of loud noises newborn babies experience show, it appears that nonhuman animals and infants experience emotions such as fear, and the same seems true of anger and disgust.

Tappolet, 2023, p. 102

So, it would be good to have a model of representation that has nonconceptual content. Analog representations seem to fit the bill here, since

analog representations can be defined as representations that tend to be continuous and that mirror what they represent, in the sense that they share structural features with what they represent. As time marches on, the hands on the watch turn. Because analog representations fail to behave like representations that have conceptual contents in that they do not allow for the systematic recombination of their contents, there are reasons to take analog representations to involve nonconceptual contents, that is, contents that do not have concepts as constituents.

Tappolet, 2023, p. 109

Creatures can represent quantities without having the concept of number, and noncreatures can represent: the clock represents time; the thermometer, temperature. I know Tappolet has (or will) say more here, but, in the chapter, it is hard (for me) to get a grasp on how values are represented in a similar manner—that is, how do they mirror what they represent? She says:

Given the assumption that the content of representations matches their format, it follows that emotions have nonconceptual contents. The receptive theory would thus have no problem to account for the fact that beings, such as nonhuman animals, who lack concepts have emotions.

Tappolet, 2023, p. 110

I would like to hear more about format/content match.

Another virtue of the view is that one does need causal contact to represent magnitude. Similarly, one can feel fear even when the object of fear is not present. In explaining this, Tappolet says:

Like analog magnitude representations, emotions can be activated in the absence of causal contact with the stimuli. We can feel fear simply because we remember a fierce tiger or because we are told that there is a tiger loose in the neighborhood. Moreover, it is clear that emotions are not tied to specific sensory modality. Your fear can be based on seeing something, but also on hearing, smelling, or tasting it, just as it can be based on a belief or a memory.

Tappolet, 2023, p. 110

And here I have another question. On this view, is an emotion always a reaction to some cognitive base? That is where the prefix “re-” in the word “receptive” comes from: “a reaction to cognitive bases (hence the ‘re’) but also to be relevantly similar to perceptions (hence the ‘ceptive’),” as Tappolet puts it (2023, p. 110).

The more straightforward perceptual theories don’t keep these steps separated. That is, we perceive the tiger as dangerous or see it as so, rather than reacting to what we see. It seems these two steps are not always there—or at least not consciously.

Returning to the question of evaluation (and this is what the next part of the book deals with more directly), I am wondering what gets evaluated and how? If the hands on the clock stop moving while time marches on, we know it is not accurately representing time’s passage. We also have other clocks to check it against. In the case of emotions, it is not clear that we have the same capacity to measure to see whether they are going wrong.

Appendices

Bibliography

- Grzankowski, Alex, “Navigating Recalcitrant Emotions,” Journal of Philosophy, vol. 117, no. 9, 2020, pp. 501-519.

- Tappolet, Christine, Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, New York, Routledge, 2023.