Abstracts

Abstract

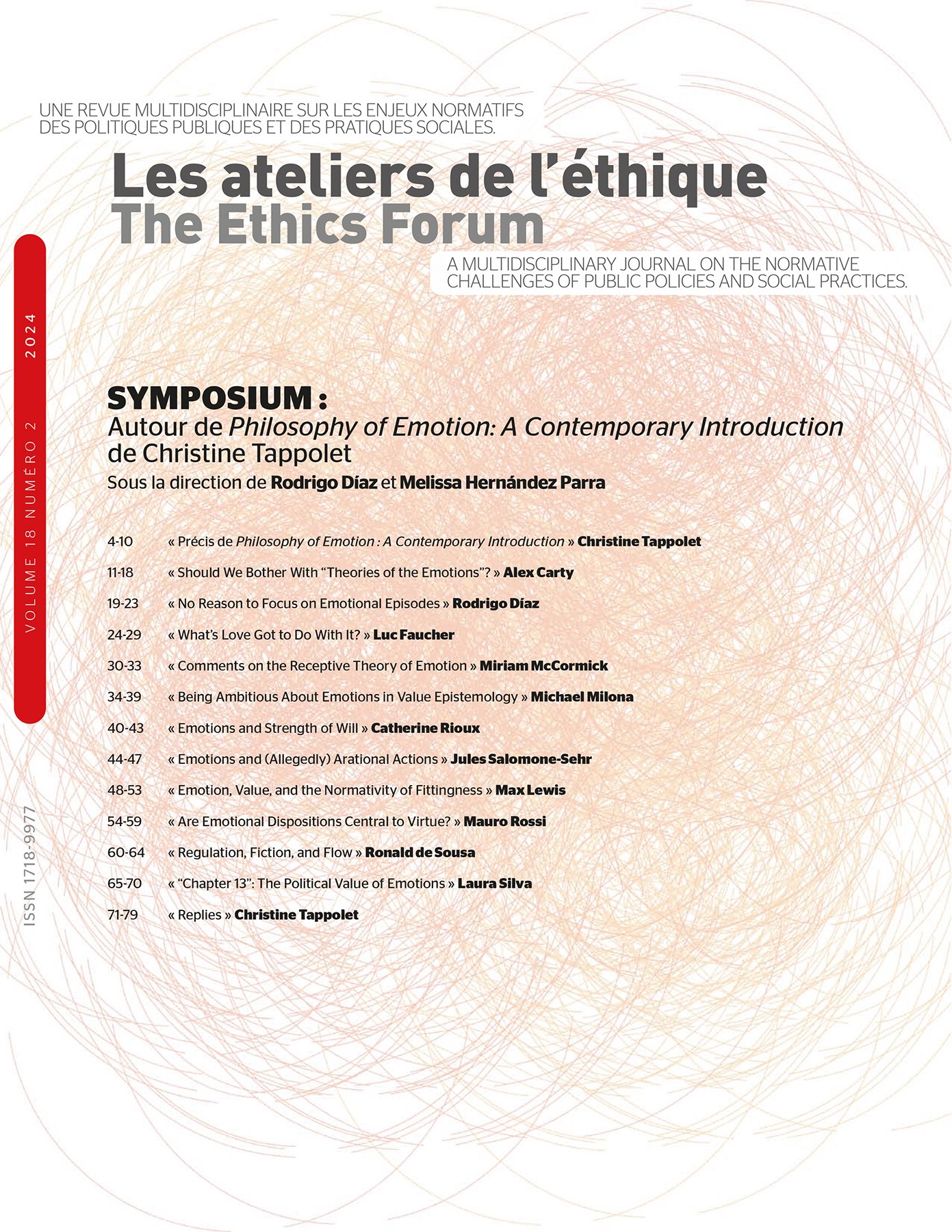

Christine Tappolet’s Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction is a comprehensive inventory of recent developments in the philosophy of emotion. Part 2 of the book examines various theories that answer the first question from chapter 1: What is the essence of emotions? My commentary compares these theories with Amélie Oksenberg Rorty’s argument for a skeptical answer to this question.

Résumé

Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction par Christine Tappolet est un inventaire complet des développements récents de la philosophie de l'émotion. La deuxième partie du livre examine diverses theories qui répondent à la première question du chapitre 1 : quelle est l’essence des émotions ? Mon commentaire compare ces théories avec l’argument d’Amélie Oksenberg Rorty en faveur d’une réponse sceptique à cette question.

Article body

I

Chapter 1 of Christine Tappolet’s Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction begins with a rich survey of the influences of the ancient and modern periods on contemporary theorizing about emotions. After that, we turn to the three central questions that guide the rest of the book:

a) The essence question: What is the essence of emotions?

b) The normative question: Are emotions good or bad for us?

c) The regulation question: Can we regulate our emotions, and if so, how?

Tappolet, 2023, p. 13

Other commentators in this symposium focus on these three questions as they appear in the remaining eleven chapters. In this article I’ll make some brief remarks about the essence question and the structure of part 2. There are three competing answers to the essence question: emotions are essentially feelings; they are essentially motivations; or they are essentially evaluations (e.g., with some sort of cognitive structure suggested by terms like “judgment,” “thought,” “appraisal,” “evaluative representation,” or “perception/perceptual experiences”). Keen on winning the battle of theory construction, each theory presents arguments in favour of thinking that feelings, motivations, or evaluations are the essential core of emotional phenomena.[1] From here, there are subsequent attempts at strengthening each theory by avoiding apparent counterexamples (e.g., unconscious emotions, emotions such as admiration that need not be connected to motivation, and recalcitrant emotions that conflict with the agent’s evaluative judgments or beliefs). Alternatively, other philosophers of emotion defend “hybrid” theories that posit several essential components. According to Andrea Scarantino (2014), for example, emotions are states that combine motivational and evaluative components.[2]

Notice, though, that many of these views defend positive answers to the question of whether emotions have an essence. These views assume from the start that there is some essence, or some indispensable core feature, of all emotions. Thus, what could be added to part 2 is a taxonomy of arguments for skeptical answers to the essence question, according to which there is no essence of emotions. Taking a cue from Wittgenstein, as Jon Elster (1999) does, one might develop such a skeptical view by glossing the concept of emotion as a “family resemblance” concept (see Tappolet, 2023, p. 62). To the best of my knowledge, an alternative skeptical view was first proposed in the work of Amélie Oksenberg Rorty (1980b; 1985; 2004) and Paul Griffiths (1990; 2001; 2004). More specifically, Rorty and Griffiths argue that the generic category of the emotions doesn’t designate a natural kind.[3] Lisa Feldman Barrett (2006; 2017) and Andrea Scarantino (2012) also defend similar views with respect to specific emotion categories, like fear and anger.

This gives us several theories that could be compared with the three views mentioned above that defend non-skeptical answers to the essence question. Section II of my commentary summarizes some noteworthy aspects of Rorty’s argument. I’ll conclude, in section III, by mentioning some nuances that shape this ongoing debate about the essence of emotions.

II

Rorty’s skeptical answer to the essence question can be summarized by the following slogan: “Notoriously, emotions do not form a natural kind [or class] distinguished from motives, moods, and attitudes” (Rorty, 2004, p. 269). In her article “Enough Already with ‘Theories of the Emotions,’” she defends this view by pointing out two similarities between theories of emotion that give non-skeptical answers to the essence question (see also Rorty 1980b; 1985). When presented with counterexamples for thinking that, say, feelings, motivation, or evaluations are essential to emotions, these theories turn to what Rorty calls the tactics of species qualification and gerrymandering emotions. Both of these tactics, she argues, turn out to undermine the explanatory power of theories that each try to identify some essential or core feature of all emotions.

Species qualification involves a series of heel-digging responses from advocates of non-skeptical answers to the essence question. Consider, for example, how an evaluative theory like judgmentalism might appeal to species qualification:

“Emotions are evaluative judgments.”

“What sort of evaluative judgments? What about stock market evaluations or evaluations of the state of the climate? The evaluative judgments of realtors, art dealers, or fine food and wine connoisseurs? Are they emotions?”

“Well, no. Emotions are a species of erroneous or incomplete evaluative judgments.”

“So ‘Socrates was a vulgar, ugly layabout’ is an emotion?”

“Emotion-judgments are a species of incomplete evaluations that are presumptively motivating.”

“So motivating desires that embed incomplete evaluations—for instance, ‘I want that juicy red apple’—are emotions?”

“Well, desire-emotions are accompanied by feelings of a certain sort.”

Rorty, 2004, p. 272

From here, the thought goes, there are further qualifications made that water down the judgmentalist’s initial claim that emotions are essentially evaluative judgments.[4] As this dialogue emphasizes, a wide range of psychological attitudes are reintroduced into a theory meant to give pride of place to only one of them.

As Rorty points out, this tactic is familiar from other areas of philosophy. The explanatory power of theories of imagination, perception, or the will, for example, don’t merely depend on how well each theory fits with folk psychology and folk speech. Their explanatory power also depends on their place in a more complete picture or theory of mental functioning. As Rorty says, the “meaning and import—the claims—of the views of Aristotle on pathe, Seneca on ira and passio, Spinoza on affectus, Hume on the passions, Rousseau on sentiment, Sartre on emotion are deeply embedded in their metaphysics and philosophy of mind, on the force of their distinctions between activity and passivity, their theories of the essential or individuating properties of persons” (Rorty, 2004, p. 270). To properly assess the explanatory power and plausibility of claims about passion, feeling, affect, sentiment, and emotion, then, we need a more complex story about how they may cohere with, or become opposed to, other psychological activities like sensation, perception, imagination, belief, desire, choice, and so on.

The second tactic Rorty identifies consists in gerrymandering emotions, or classifying varieties of them among several other distinctions in philosophy and psychology. Gerrymandering, as Rorty defines it, involves placing emotions within a larger framework of distinctions between (1) mental states and mental activities, (2) between cognition and motivation, (3) between perceptions and proprioception, (4) between voluntary and nonvoluntary states, (5) between physical and psychological conditions, or even (6) between psychological states primarily explained by physical processes and psychological states neither reducible to nor adequately explained by physical processes.[5] Different theories of emotions, having been gerrymandered in one or more of these ways, are then evaluated on the basis of their elegance and simplicity, as well as their ability to account for different emotional phenomena while avoiding counterexamples.

There are several issues with gerrymandering. I’ll mention just two. First and foremost, emotions seem to resist being neatly categorized one way or another with these parameters (see Rorty, 2004, pp. 272-275). As Rorty puts it, “[what] makes the placing of emotions along a schema of these various parameters problematic is that the meanings and force of these dichotomies have themselves shifted” (Rorty, 1980a, p. 2). One example she mentions is the contentious history of the distinction between active and passive responses. There is a substantive debate about the relation between, on the one hand, active and passive actions and, on the other hand, actions that are voluntary as opposed to involuntary (see Frankfurt, 1976).

Second, and relatedly, emotions involve an incredibly diverse set of phenomena exhibiting opposing characteristics within the larger framework of distinctions. Some bouts of love are active, while other bouts of love are passive. Moreover, emotions can be described more generally as being more or less voluntary, or completely involuntary. On the one hand, bouts of anger can be so involuntary they render irrelevant the question of whether the person chose to have them or not. That question is, as Rorty observes, “a question with such a tangle of counterfactual hypotheses that we need to reconstruct the person’s entire history and constitution to make sense of it” (Rorty, 1985, p. 346). On the other hand, a person’s susceptibility toward certain emotions, like anger, is sometimes what we blame them for.[6] This would be the case if that emotional susceptibility is something that arises out of policies the person adopts voluntarily.[7]

The lesson here is that the general category of emotions complicates these commonplace distinctions in philosophy and psychology. Theories of emotion, when they are gerrymandered, must be assessed for “their relative elegance, simplicity, richness, and completeness in encompassing what are (currently) taken to be the relevant phenomena of the field, as well as for the plausibility of their ingenuity in absorbing or excluding objections and counterexamples” (Rorty, 2004, p. 273).

III

To conclude, let’s return to theories that defend non-skeptical answers to the essence question. In her discussion of “theories of emotions,” Rorty wishes to draw attention to the following observations:

In short: theories of the “emotions” (1) do not “cut at the joints”: their subject matter encompasses a heterogeneous set of attitudes, not sharply distinguished from motives, moods, propositional attitudes; (2) are comprehensible only within a larger frame of a relatively complete philosophy of mind/philosophical psychology.

Specific “emotional” attitudes are individuated and identified (1) within a nexus of supportive and opposed attitudes that are characteristically (2) within the context of a narrative scenario. (3) A culture’s repertoire of “emotions” is structured by its economic, political, and social arrangements.

Rorty, 2004, p. 278

My commentary has focused on Rorty’s argument, but the arguments developed by Griffiths, Elster, Barrett, and others are worth engaging with as well.

Several outstanding issues shape this ongoing debate about the essence question. First, Robert C. Roberts (1988) has challenged Rorty’s claim that emotions don’t form natural a kind.[8] Second, setting aside any critical responses, we should note how challenging it is to successfully defend this negative claim. As Rorty observes, “this is not the sort of claim that can be demonstrated: at best it can be grounded in detailed discussions of the problems that arise in identifying, explaining, characterizing those various conditions that are commonly classified as emotions” (Rorty, 1980a, p. 3). Third, Rorty specifically tries to argue for the impossibility of capturing the essence of emotions by treating them as a natural kind.[9] However, one might agree with Rorty that emotions aren’t a natural kind, but still try to give a positive answer to the question of whether emotions have an essence.[10] Indeed, several philosophers have defended the claim that emotions are sui generis mental states irreducible to other kinds of mental states.[11]

Nonetheless, I think Rorty does a remarkable job of identifying problems for theories of emotion in the business of giving non-skeptical answers to the essence question. A survey of the various skeptical perspectives on the essence question and extant critical responses would be a valuable addition to part 2.[12]

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Also, due to some groundbreaking articles by Hichem Naar (2022; 2024), a new theory of emotions, which he calls the agential theory, has recently hit the scene. The agential theory is supported by the action analogy, according to which emotions are fundamentally action-like. This rivals perceptual theories that characterize the appraisals of emotions as fundamentally perception-like. But the agential theory, as Naar defines it, doesn’t identify an essential connection between emotions and action. Instead, it maintains that “emotions bear an intimate relation to certain action types [like punishing and kissing],” and that “there should be something about emotions themselves that is [fundamentally] action–like” (Naar, 2024, p. 71). And while the agential theory is “fruitless if no genuine account of emotions is ultimately provided,” Naar says progress can be made on systematizing and elucidating various features of emotions “without having a preferred theory from the outset” (Naar, 2022, pp. 2731-2732).

-

[2]

I borrow this terminology of “hybrid” theories from Tappolet, though she adds that it’s unclear whether Scarantino’s theory should qualify as one (see Tappolet, 2023, pp. 62-63, 85-86). Theories that posit just one essential component and view the rest of them as inessential are called “pure” accounts.

-

[3]

For others who deny that the generic category emotion designates a natural kind, see Kagan (2007; 2010), Russell (2003), and Zachar (2006). Following Rorty and Griffiths, I’ll use the term “natural kind” to stand for real, naturally occurring entities or categories that are discoverable via scientific concepts and classifications.

-

[4]

This resembles what Andrea Scarantino and Ronald de Sousa call the “elastic strategy,” where the meaning of the concept of judgment is stretched, perhaps in an ad hoc way, to accommodate these sorts of counterexamples. For further discussion, see Scarantino and de Sousa (2021) and Scarantino (2010).

-

[5]

Compare with Rorty’s earlier comments about this kind of tactic, though there she did not use this specific terminology of “gerrymandering” (see Rorty, 1980a, pp. 1-3; 1980b, pp. 104-05).

-

[6]

Rorty also makes similar observations elsewhere about the cognitive and physical characteristics of emotion: “We sometimes hold people responsible for their emotions and the actions they perform from them. Yet normal behavior is often explained and excused by the person ‘suffering’ an emotional condition. […] Sometimes emotions are classified as a species of evaluative judgments whose analysis will be given in an adequate theory of cognition. But sometimes the cognitive or intentional character of an emotion is treated as dependent on, and ultimately explained by, a physical condition” (Rorty, 1984, p. 521).

-

[7]

Although one issue here is whether “voluntarily” means the person has voluntary control over their emotion, or, alternatively, it means their emotion somehow reflects their evaluative judgments or appraisals. For further discussion, see Smith (2005).

-

[8]

See also Roberts (2003, ch. 1).

-

[9]

In a similar manner, Griffiths (1997; 2004) qualifies his skeptical arguments to target theories that identify the essence of emotions in terms of natural kinds.

-

[10]

Thanks to an anonymous referee for bringing up this helpful point.

-

[11]

There are plenty of examples that could be cited here, but see, inter alia, D’Arms and Jacobson (2003), de Sousa (1987), Goldie (2000), and Mitchell (2021). For further discussion, see Tappolet (2016, ch. 1).

-

[12]

I would like to thank Rodrigo Díaz, Melissa Hernández Parra, and an anonymous referee for The Ethics Forum for their very thorough comments. Thanks also to Jordan Walters, Guillaume Soucy, Sacha-Emmanuel Mossu, Gabriel Saso-Baudaux, and (once again) Melissa Hernández Parra for many insightful discussions in our reading group on the philosophy of emotion. Finally, I’m grateful to Guillaume for his work coordinating our reading group on Christine’s book with the Groupe de Recherche Interuniversitaire sur la Normativité (GRIN).

Bibliography

- Barrett, Lisa Feldman, “Are Emotions Natural Kinds? Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 1, no. 1, 2016, pp. 28-58.

- Barrett, Lisa Feldman, How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of The Brain, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

- D’Arms, Justin and Daniel Jacobson, “The Significance of Recalcitrant Emotion,” in Anthony Hatzimoysis (ed.), Philosophy and the Emotions, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 127-135.

- de Sousa, Ronald, The Rationality of Emotion, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1987.

- Elster, Jon, Alchemies of the Mind: Rationality and the Emotions, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Frankfurt, Harry, “Identification and Externality,” in Amélie O. Rorty (ed.), The Identities of Persons, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1976, pp. 239-252.

- Goldie, Peter, The Emotions: A Philosophical Exploration, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Griffiths, Paul, What Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological Categories, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Griffiths, Paul, “Emotion and the Problem of Psychological Categories,” in Alfred W. Kazniak (ed.), Emotions, Qualia, and Consciousness, Singapore, World Scientific Publishing, 2001, pp. 28-41.

- Griffiths, Paul, “Is Emotion a Natural Kind?,” in Robert Solomon (ed.), Thinking About Feeling: Contemporary Philosophers on Emotions, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 233-249.

- Kagan, Jerome, What is Emotion? History, Measures, and Meanings, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2007.

- Kagan, Jerome, “Once More into the Breach,” Emotion Review, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010, pp. 91-99.

- Mitchell, Jonathan, Emotions as Feelings Towards Value, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Naar, Hichem, “Emotion: More like Action than Perception,” Erkenntnis, vol. 87, no. 6, 2022, pp. 2715-2744.

- Naar, Hichem, “Emotions and the Action Analogy: Prospects for an Agential Theory of Emotions,” Journal of the American Philosophical Association, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024, pp. 64-87.

- Roberts, Robert Campbell, “What an Emotion Is: A Sketch,” The Philosophical Review, vol. 97, no. 2, 1988, pp. 183-209.

- Roberts, Robert Campbell, Emotions: An Essay in Aid of Moral Psychology. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Rorty, Amélie O., “Introduction,” in Amélie O. Rorty (ed.), Explaining Emotions, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1980a, pp. 1-8.

- Rorty, Amélie O., “Explaining Emotions,” in Amélie O. Rorty (ed.), Explaining Emotions, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1980b. pp. 103-126.

- Rorty, Amélie O., “Aristotle on the Metaphysical Status of Pathe,” Review of Metaphysics, vol. 38, no. 1, 1984, pp. 521-546.

- Rorty, Amélie O., “Varieties of rationality, varieties of emotion,” Social Science Information, vol. 24, no. 2, 1985, pp. 343-353.

- Rorty, Amélie O., “Enough Already With ‘Theories of the Emotions’,” In Robert Solomon (ed.), Thinking About Feeling: Contemporary Philosophers on Emotions, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 269-278.

- Russell, James A., “Core Affect and the Psychological Construction of Emotion,” Psychological Review, vol. 110, no. 1, 2003, pp. 145-172.

- Scarantino, Andrea, “Insights and Blindspots of the Cognitivist Theory of Emotions,” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, vol. 61, no. 4, 2010, pp. 729-768.

- Scarantino, Andrea, “How to Define Emotions Scientifically,” Emotion Review, vol. 4, no. 4, 2012, pp. 358-368.

- Scarantino, Andrea, “The Motivational Theory of Emotion,” In Justin D’Arms and Daniel Jacobson (eds.), Moral Psychology and Human Agency: Philosophical Essays on the Science of Ethics, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 156-185.

- Scarantino, Andrea, and Ronald de Sousa, “Emotions,” in Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2021. URL: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/emotion

- Smith, Angela M., “Responsibility for Attitudes: Activity and Passivity in Mental Life,” Ethics, vol. 115, no. 2, 2005, pp. 236-271.

- Tappolet, Christine, Emotions, Values, and Agency, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Tappolet, Christine, Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction, New York, Routledge, 2023.

- Zachar, Peter, “The Classification of Emotion and Scientific Realism,” Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, vol. 26, no. 1-2, 2006, pp. 120-138.